We all love images of children. Politicians, aware of their capacity to evoke empathy and a sense of shared humanity, are endlessly being photographed with them. Social media is littered with thousands upon thousands of adorable variations. What then makes a particular child stand out? This is a question I asked myself recently while looking through a selection of images for inclusion in the exhibition ‘Sugar’, which will be on display at the Gallery as part of the Cultural Centre’s programs celebrating ‘150 years of Australian South Sea Islander contributions to Queensland’. ‘Sugar’ features historical photographs as well as contemporary art works to reflect on the history of the sugar industry in Queensland, with a particular focus on the contribution of South Sea Islanders and their descendants.

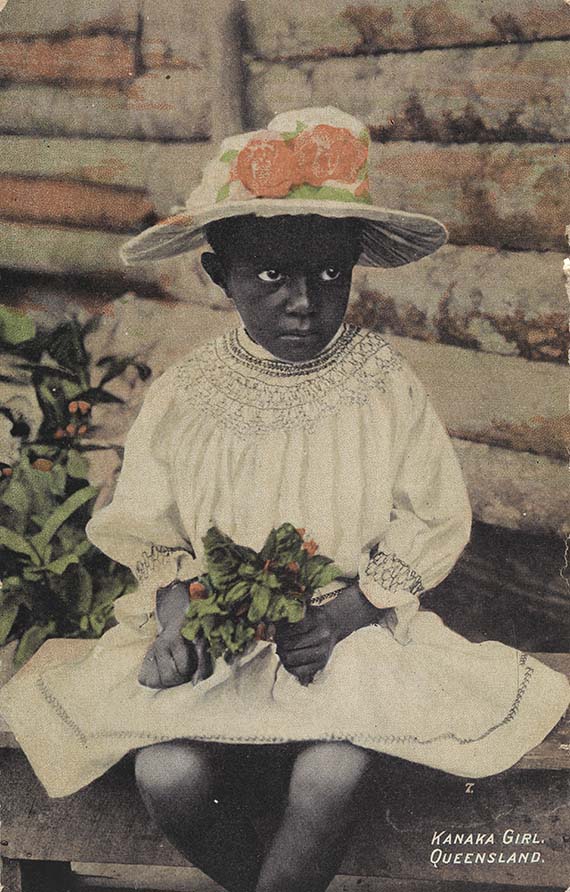

The image of a child that captured my attention derives from a photograph taken of a young South Sea Islander girl in the late nineteenth century. It was reprinted in the early twentieth century in Great Britain as a colourised postcard. Looking at this postcard, now held in the Collection of the Gallery, I am reminded of the many photographs taken at this time, of Indigenous and Pacific peoples that asserted particular racial stereotypes.

In many of these colonial-era images, the subjects are depicted in traditional attire, or are objectified as ‘specimens’ observable from every angle. Such images fed into early pseudo-scientific approaches to racial studies such as phrenology. Many contemporary Indigenous and Pacific artists have used such archival images as a basis for their critique of colonial histories and their often derogatory representations.

Fully clothed in a beautiful white smocked dress and hat, the young child in this photograph appears to have been dressed and positioned to engage with European perceptions of what constitutes innocence and civility. The postcard is overprinted with the title ‘Kanaka girl, Queensland’. ‘Kanaka’ is a term which was widely used at this time to describe South Sea Islander labourers brought from Melanesia to Queensland and Northern New South Wales to work on sugar and cotton farms between 1863 and 1906. Contributing significantly to this industry, these South Sea Islander men, women and children were viewed and treated by colonial landowners and authorities as a form of cheap and compliant labour. Supporting this idea, the child photographed for this image, has been presented separated from her family and community – alone and unthreatening.

There is something, however, about this child that speaks beyond this. Very young – not much beyond six or seven years of age – she has obviously been dressed and posed by an adult to play a particular part. She looks reticent about this and looks off-camera, perhaps towards a known adult, for either reassurance or further instruction. What I find compelling about this young girl is that while she doesn’t appear scared, there is wariness and preparedness to her pose that, for me, speaks volumes about the precarious position that South Sea Islanders were in at the time here in Queensland. This history is a painful one, and this young girl appears to eloquently communicate her knowledge of this and her ability to face it nonetheless with dignity. In doing so, she embodies the strength and resilience of the Australian South Sea Island community that inherited this history.

‘Sugar’ opens at the Queensland Art Gallery (QAG) from 8 June.