The QAGOMA Foundation assists with Gallery conservation activities such as supporting complex treatments, technical art history studies, innovative research and analysis that frequently leads to publication and contributes to a wider body of industry knowledge, and enabled a research project with the Heritage Conservation Centre, Singapore.

We delve into recent investigations into the materials and methods of two mid-century Australian contemporaries — Charles Blackman and Sidney Nolan — as well as colonial Queensland artist JH Grainger.

RELATED: ART CONSERVATION projects

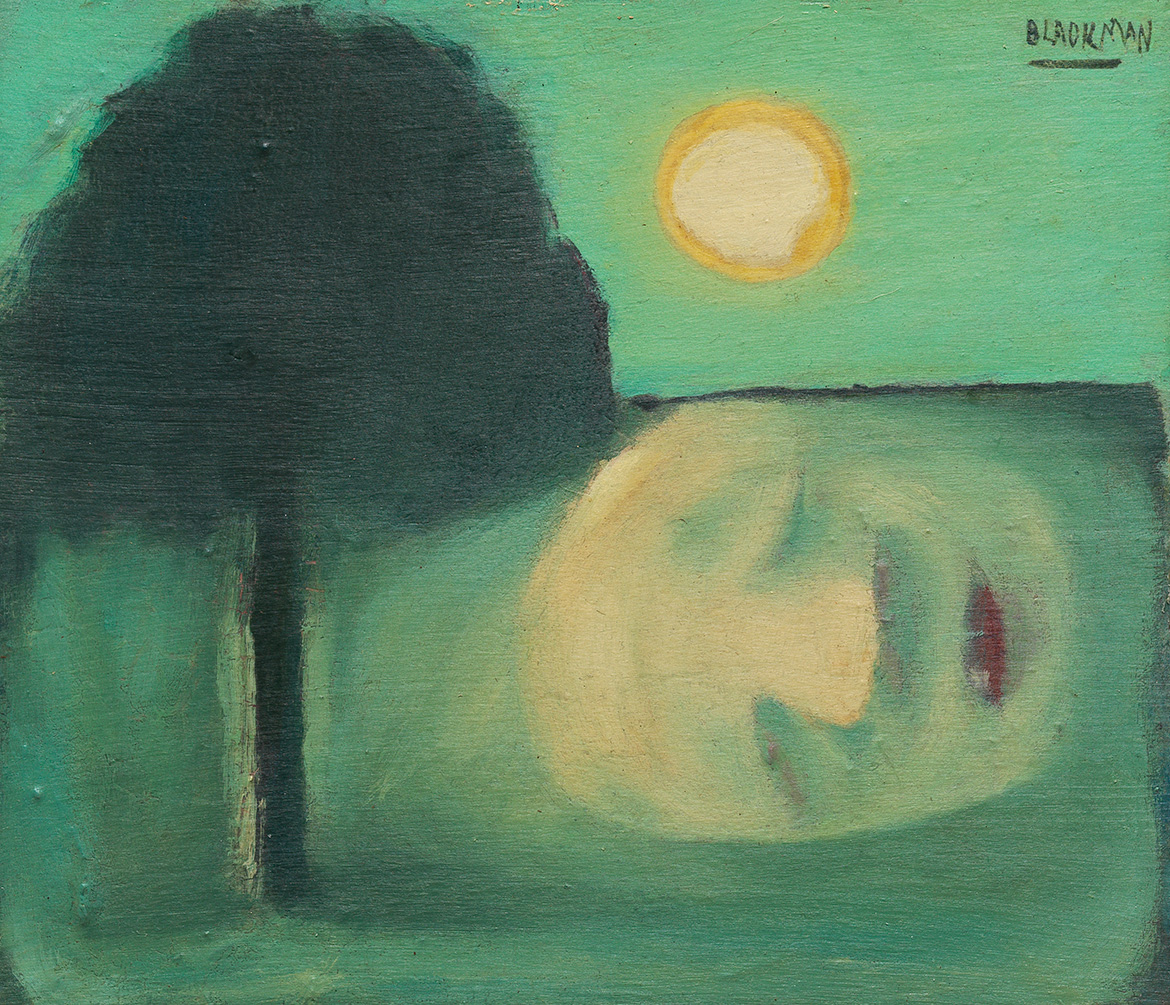

Charles Blackman

Gallery conservators were able to determine that Charles Blackman used unconventional mediums, such as house paints, to create his works.1 He was also blending his own paint formulations2 to create compositions that are a melange of matt and gloss paints, applied in multiple layers, which he then made additionally complex through impasto and sgraffito techniques.3

Sidney Nolan

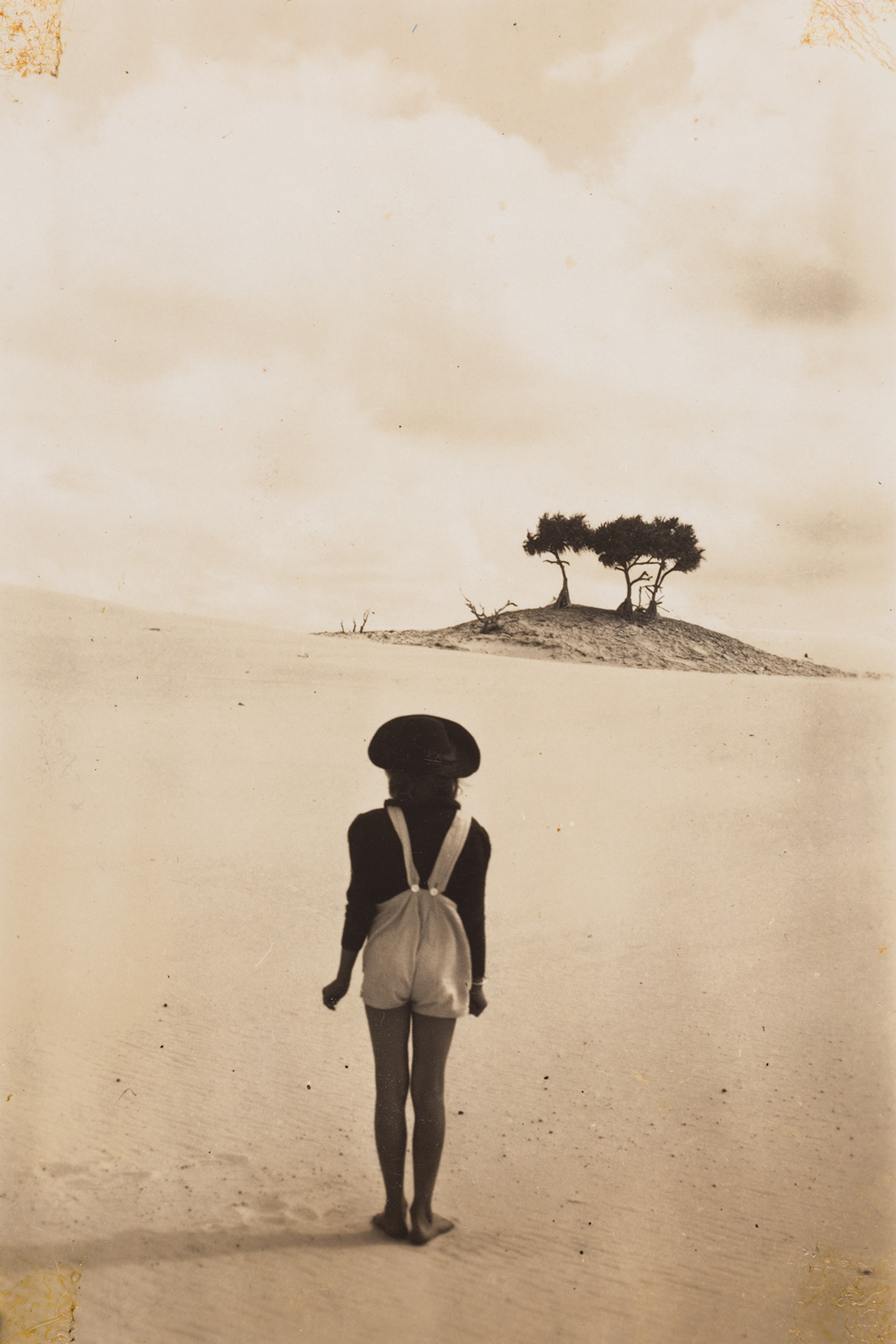

The ‘Nolan in Queensland’ conservation project involved the investigation of three works in the Collection, and saw conservators turn sleuth in an effort to piece together the compelling story of Sidney Nolan’s time on Fraser Island. Through considered detective work, painting conservator Anne Carter was able to locate and interview 80-year-old Anita Rafferty (pictured in Anita Rafferty at Indian Head, Fraser Island 1947), the daughter of Norm Crombie, a forestry overseer on Fraser Island who hosted Nolan’s visit in 1947. Anita was just ten at the time, but remembers posing for Nolan in photographs he took on the beach at Indian Head.4

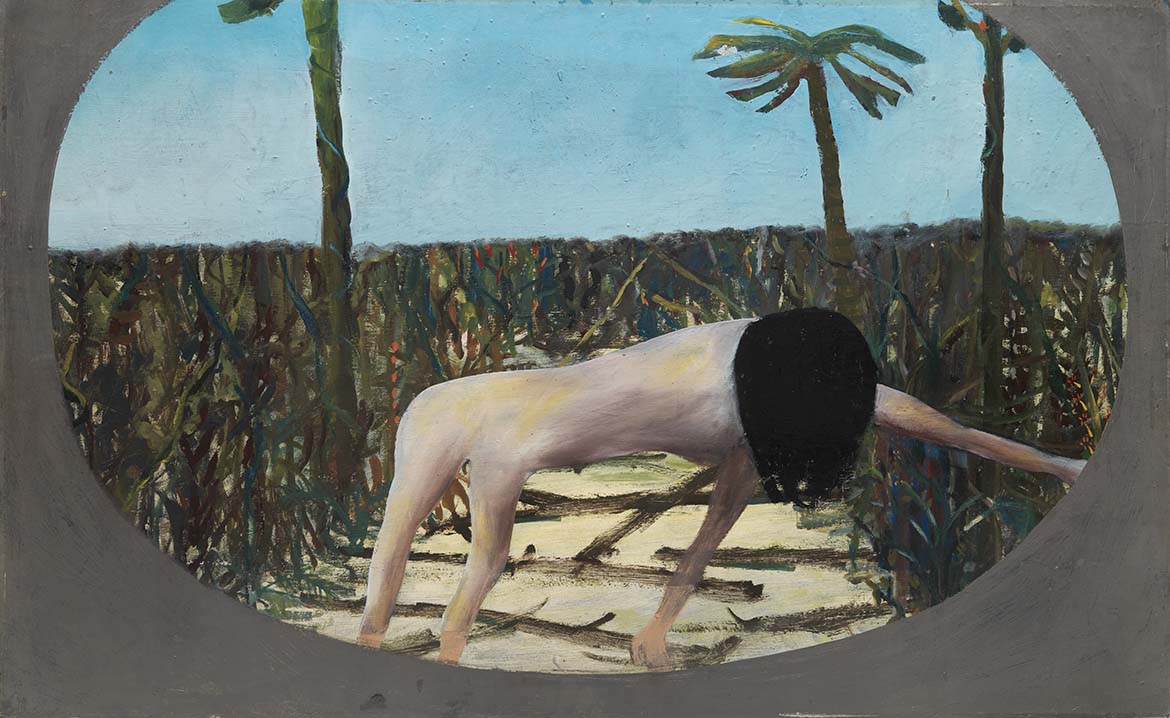

Anne Carter’s investigation and analysis of two of Nolan’s works in the Collection — Platypus Bay, Fraser Island and Mrs Fraser, both 1947 — reveal the use of masonite supports sourced from demolished buildings on Fraser Island.5 A forensic examination of Mrs Fraser revealed at least six alterations to the work, and the inclusion of a painted oval spandrel reducing the composition, followed later by the cutting down of the masonite support.6

JH Grainger

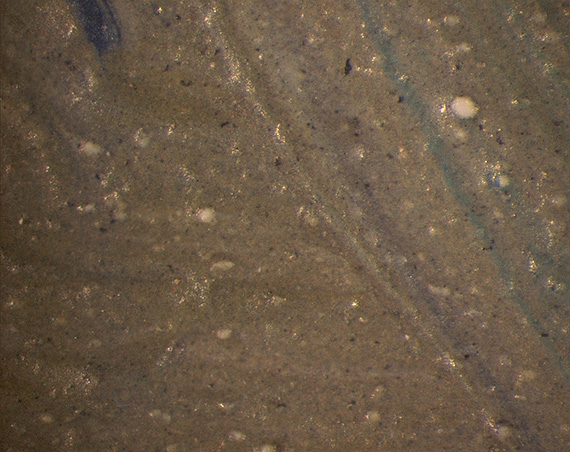

Queensland artist JH Grainger’s Turtle island c.1889 is a rare and peculiar example of colonial painting. A founding member of the Queensland Art Society, Grainger was also the recipient of the 1897 Queensland International Exhibition gold medal for a seascape.7 This curious painting incorporates printed images of turtles that have been cut out and attached to the painted canvas as collage-like inclusions, which is a highly unusual technique for an artist practising in the 1880s. The project to restore this painting is a major undertaking, involving specialists from paintings, paper and framing conservation.

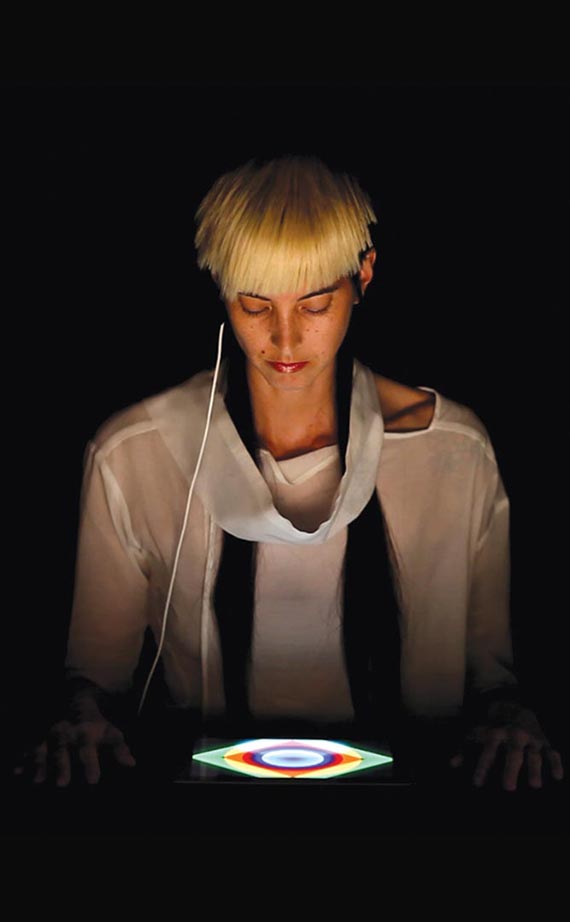

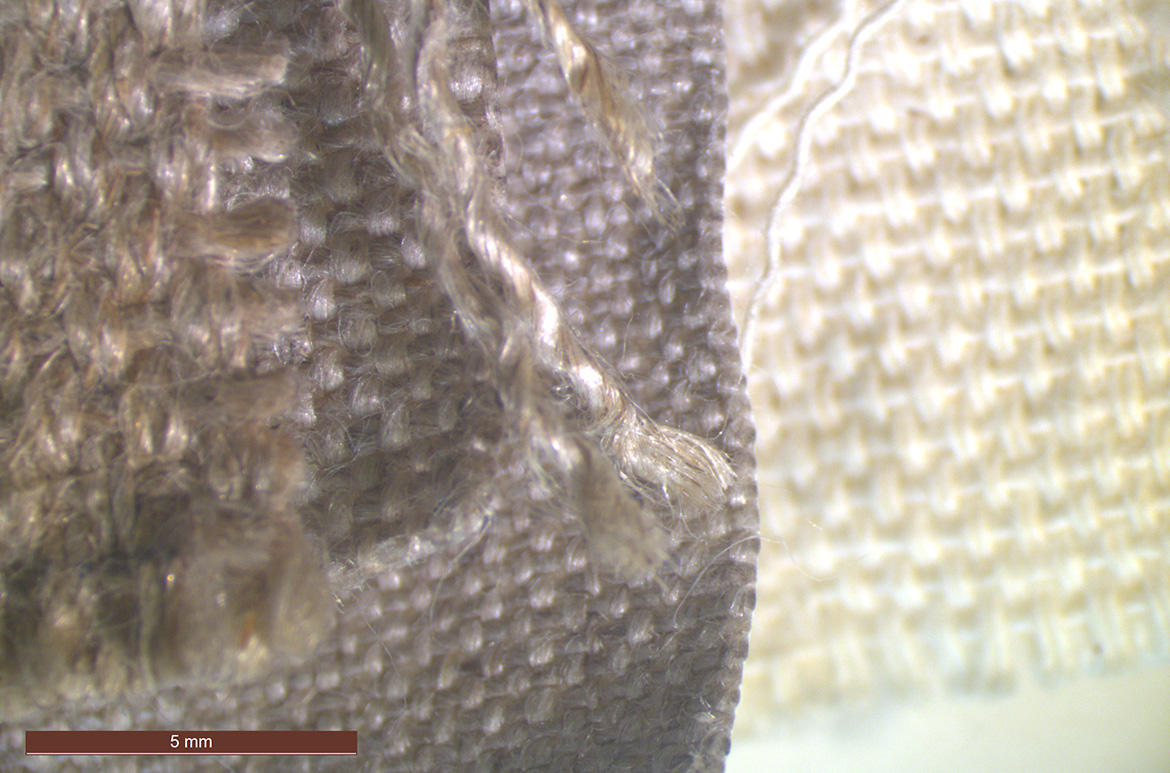

Foundation fundraising has also been directed towards a major collaborative research project with colleagues at Singapore’s Heritage Conservation Centre (HCC), designed to investigate contemporary pre-primed artist canvases and grounds. Little is known about contemporary canvas fibres or the formulas used to prepare their ground layers, but these preparatory elements have a significant effect on the behaviour and stability of subsequent paint layers, greatly influencing the aging characteristics of pigments and paints. Understanding these elements is vital to conservation treatment of contemporary painted works, and its outcomes.

Through the generous support of the Foundation, these meticulous research and analysis projects, and technically complex treatments, are able to contribute to our collective knowledge and understanding of the Gallery’s Collection.

Amanda Pagliarino is Head of Conservation and Registration, QAGOMA

Endnotes

1 Felicity St John Moore, Charles Blackman: Schoolgirls and Angels: A Retrospective Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings by Charles Blackman [exhibition catalogue], National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 1993, p.17.

2 Anne Carter, ‘Blackman’s house paints: Icy blues and blood reds’, Lure of the Sun: Charles Blackman in Queensland [exhibition catalogue], Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, 2015, p.40.

3 The full story of this research appears in the QAGOMA publication Lure of the Sun: Charles Blackman in Queensland (2015).

4 Carter, notes from an interview with Anita Rafferty (QAGOMA unpublished material), recorded 18 February 2016.

5 Carter, research notes (QAGOMA unpublished material), 2016. Research findings from the ‘Nolan in Queensland’ conservation project are published as a chapter in a forthcoming Getty Publications publication titled Sidney Nolan: The Artist’s Materials.

6 Carter, research notes (QAGOMA unpublished material), 2016.

7 Glenn Cooke, ‘Turtle island essay’ (QAGOMA unpublished material), September 2010.

#QAGOMA