‘My Country, I Still Call Australia Home: Contemporary Art from Black Australia’ examines strengths within the Queensland Art Gallery collection of Indigenous art and recognises three main central themes: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander versions of history; responses to contemporary politics and experiences; and connections to place. These themes are expressed in the three main Gallery spaces as the visual chapters: ‘My history’, ‘My life’ and ‘My country’.

The ‘My country’ thematic is the spine of this exhibition, interrupting, punctuating and reinforcing the claims made over history and contemporary politics, reiterating the meaning of country for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

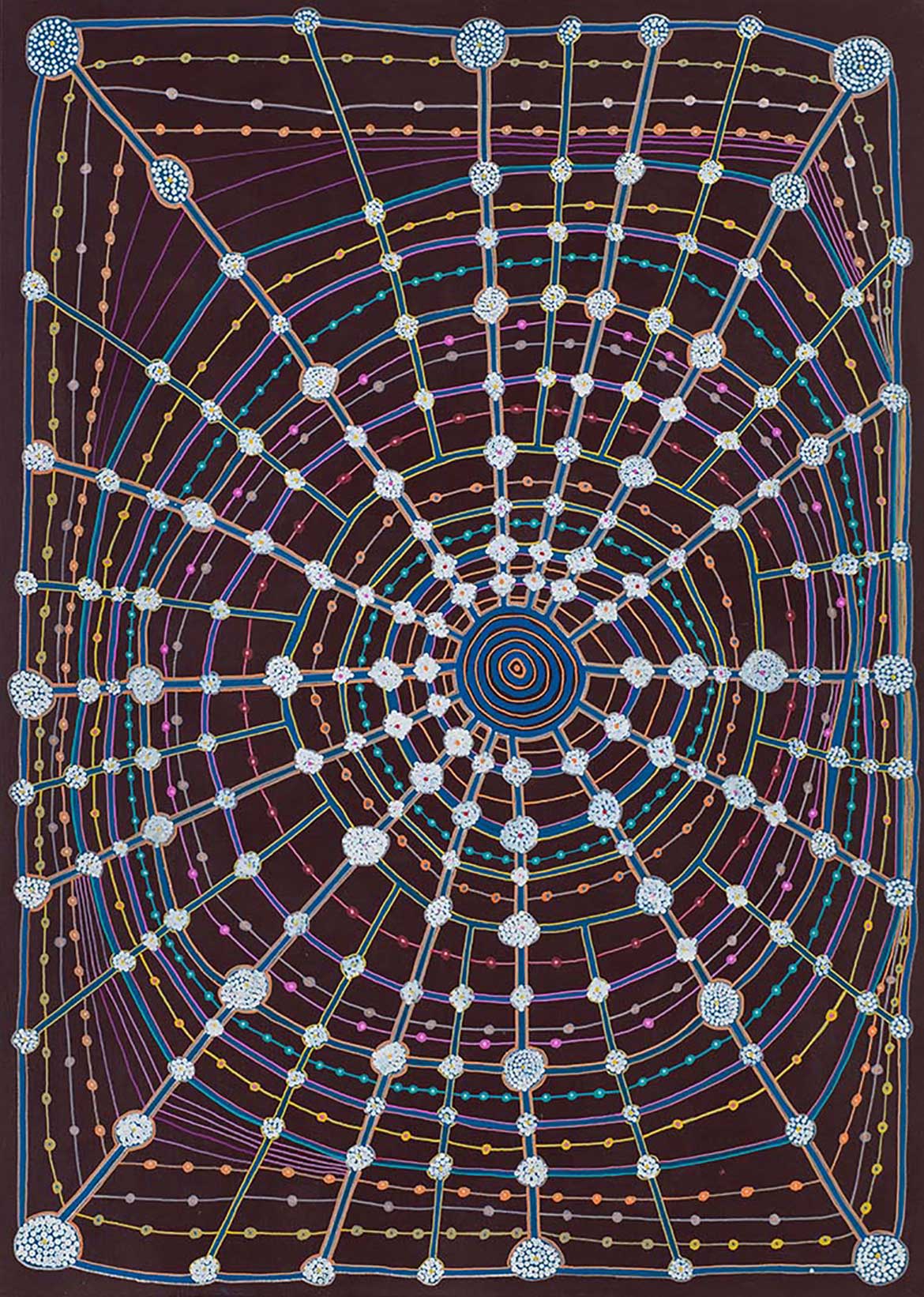

Hetti Perkins’s essay about the works included in ‘My country’ eloquently explains the inextricable links to special sites that these artists continually emphasise through bold and expressive paintings. Each work stakes a claim on behalf of its artist: ‘This is my story, this is my place. I have a dream(ing) that you will recognise my connection to these sacred places as you revere your own holy sites and places of historical significance.’ Every one of these places has been sung about and is still celebrated today in the same manner as holy and sacred sites in Jerusalem, Gallipoli and Kokoda. They are no less significant to First Nations people. The works sing their own songs, songs about place, deeds, ancestors and family.

Interestingly, some of the most iconic Australian songs and poems were written overseas — including Peter Allen’s ‘I Still Call Australia Home’ and Dorothea MacKellar’s ‘My Country’ — and illustrate how being away from home strengthens attachment to it. Many painters in central Australia were removed from their original homelands. Even those still on their lands have been tied to government-approved and administered settlements that are often away from the places of their Tjukurrpa,17 their dreaming sites. Likewise, a number of artists in this exhibition feel that same yearning for their motherland, painting in response increasingly large and bold works that simultaneously reaffirm their connection to these places and provide a financial means for them to do so.

Some works in the exhibition, such as Uta Uta Tjangala’s Umari Dreaming site 1983, were part of a push to return to ‘homeland’ settlements closer to sacred and ceremonial sites in the artist’s country, while others, such as Wakartu Cory Surprise’s Mimpi 2011, evolved from the collaborative map paintings used in Native Title claims to reclaim country. Some artists use painting to pass on sacred ancestral narratives through a collaborative ‘teaching and learning’ process. Ngayuku ngura (My country) Puli murpu (Mountain range) 2012 is the work of three generations of women: grandmother Ruby Tjangawa Williamson, daughter Nita Williamson and grandaughter Suzanne Armstrong. This work is as much about psychologically and physically ‘returning to country’ as a family as it is a lustrous, beautiful celebration of ngura nganampa rikina (our brilliant country), in the mountain ranges near the South Australia/Northern Territory border.

When combined, many works in ‘My Country’ effectively form a huge map, from near the Queensland/Northern Territory border in the east to the Western Australian coast. Each embodies a profound attachment to sites across the arid centre and western deserts, documenting a vital land, one far removed from ‘dead heart’ ideologies. Other works by senior and important Queensland artists tell of this state’s important places, while Megan Cope’s site-specific installation explores Aboriginal links to highly populated urban spaces by inserting (Ab)original place names on vintage military survey maps. Here, Cope worked with the landscape of the greater Brisbane region, connecting it to her Quandamooka (Moreton Bay and Stradbroke Island) people and grounding the exhibition in the country on which it is held.

The thread that binds all the disparate artists in ‘My Country, I Still Call Australia Home: Contemporary Art from Black Australia’ is a desire to share their experiences, and tell stories that bring to light their contemporary lives. From paintings and sculptures about ancestral epicentres, through to photographs and videos that challenge Australia’s established history, to installations responding to the political and social situations affecting all Indigenous Australians, Black life in Australia is presented in all its vibrancy, diversity and beauty.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have made an invaluable contribution to Australian history, politics, society and art, particularly considering the size of our population. Reko Rennie’s commission Trust the 2%ers 2013 uses an urbanised version of his Kamilaroi / Gamilaraay / Gummaroi diamond designs in pink, green, blue and black to claim space and mark territory, musing on their origins as tree carvings. Rennie, proud of being one of the Indigenous two per cent of Australian society, exuberantly exclaims ‘2%er’ in gold paint. Rennie is proud, and rightly so. All Australians should be equally proud of this section of our population, which has contributed so much to our lives, to our place. The works in ‘My Country, I Still Call Australia Home: Contemporary Art from Black Australia’ tell important stories from a crucial part of Australian society. The 2%ers.

Endnote

17 Tjukurrpa is used here as the most popular Aboriginal language translation of the concept of the dreaming, used in many languages in Central Australia and the Western Desert.

‘This land is mine / This land is me’ is an extract from the 2013 exhibition catalogue ‘My Country, I Still Call Australia Home: Contemporary Art from Black Australia’ by Bruce McLean.

Bruce McLean is Curator, Indigenous Australian Art, QAGOMA