‘Sublime: Contemporary Works from the Collection’ draws together culturally diverse points of contact with notions of the sublime through major works from QAGOMA’s Australian and international collections. Here, we trace some of the multiple historical and cultural narratives surrounding the sublime.

In the last 30 years there has been sustained attention to concepts of the sublime in philosophy and in contemporary art writing, which has generated a vast critical literature. This year’s nineteenth Biennale of Sydney, ‘You Imagine What You Desire’, was conceived by curator Juliana Engberg in relation to a particular understanding of the sublime, linked to desire and the unconscious.

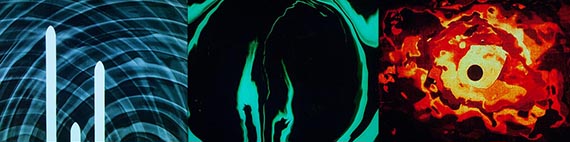

Most discussions of a contemporary sublime refer to European and North American art. Some refer to the Romantic era’s explorations of ‘the incommensurability of the sensible to the metaphysical (to the Idea, to God)’1, others to abstract painting’s ‘virtually ungraspable allusions to the invisible within the visible’2. The concept of a digital sublime has recently emerged, in which the experience of infinity previously associated with the natural world is now linked to the digital realm. Many writers also reference a technological or ecological sublime, of man-made catastrophe and humanity’s life-threatening intervention in the natural world.

‘Sublime’ includes major works drawing on widely differing aesthetic heritages and explores the resonance of ideas of the sublime in different cultural contexts. Timo Nasseri, a German artist of Iranian descent, melds the sublime geometries of Islam in his sculptural works. The polished metal and geometric forms of Epistrophy VI 2012 transform the cupola-like muqarnas of Islamic architecture to create a portal into an endlessly reflected world, placing the viewer within its infinite geometry.

The writings of Immanuel Kant, and particularly his idea of the ‘un-presentable’, or that which cannot be represented, are central to recent discussions of the sublime. Interestingly, Kant refers to different cultural sensibilities in developing his argument. His Critique of Judgement (1790) discusses the laws handed down by Moses on Mount Sinai in relation to the sublime, suggesting that there is no more sublime passage than the commandment, ‘Thou shall not make unto thyself any graven image, nor any likeness either of that which is in heaven, or on the earth, or yet under the earth’. The examples of Judaism and Islam allow Kant to argue that when representation is lacking, the imagination becomes more powerful and the experience of the sublime is linked to ‘a presentation of the infinite’. For Kant, Islam approaches a sublime religion of pure reason; his development of the concept of the sublime relies on this reflection on cultural difference.

In European art from the mid eighteenth to mid nineteenth century, the sublime became associated with Romanticism’s evocation of the experience of infinity and vertiginous uncertainty, notably through mountainous landscapes, clouds, mists, and the powerful natural forces of storms and volcanoes. Various contemporary works in the exhibition engage with concepts of the sublime deriving from the Romantic era, including Bill Viola’s early video work Chott el-Djerid (A portrait in light and heat) 1979 with its extreme landscapes of desert and ice, and Bill Henson’s Untitled 2008–09, depicting a mysterious island in dramatic chiaroscuro composition of clouds, rocks and water.

Another notion of the sublime crystallises around forms of abstraction that developed from the 1910s to the 1950s in Europe and North America. Abstraction as the end point of painting in European modernism resonates with Kant’s reflections on the sublime and with what is intimated through geometry and abstraction that cannot be represented. For French philosopher Jean-Francois Lyotard, Kant heralds a solution to ‘the problem of sublime painting’; that is, how abstraction offered an escape from the limits of figuration.3 Works by Oskar Fischinger, Lara Favaretto, Suzanne Kriemann and others play out this discussion within the exhibition. The Gallery recently acquired Fischinger’s Raumlichtkunst (Space-Light-Art) c.1926/2012, a recreation of his historic multimedia performances that brought together abstract art, cinema and music, as a three-channel high-definition video installation.

Contemporary philosophical discussions link the sublime to the catastrophies of historical proportions that marked the twentieth century. War and genocide on a previously unimaginable scale provided instances of un-representable horror. Enlightenment beliefs and assumptions about knowledge’s role in improving the human condition through technological and social progress were brought radically into question. In the exhibition, Latifa Echakhch’s A chaque stencil une revolution (For each stencil a revolution) 2007, with its wall of weeping blue pigment, speaks to utopian hopes lost and lamented, as do Nalini Malani’s powerful Mutant II and Mutant III 1996 drawings.

In dialogue, the works in the ‘Sublime’ exhibition testify to a contemporary condition of uncertainty in relation to ideas of progress, whether artistic, technological or social. They also suggest a way forward for contemporary art and culture more broadly through increasingly sensitive forms of interpretation and translation between cultural systems.

Endnotes

1 Philip Lacoue-Labarthe, ‘Sublime truth’, in Jean Francois Courtine (ed.), Of the Sublime: Presence in Question, State University of New York Press, Albany, 1993, p.89.

2 Jean-Francois Lyotard, ‘Presenting the unpresentable: the sublime’, Artforum, no.20, vol.8, April 1982.

3 Jean-Francois Lyotard, ‘L’instant, Newman’, in L’Inhumain, Editions Galilee, Paris, 1988, p.96.