Two remarkable paintings by Australian artist Anne Wallace draw attention to a dark chapter in Brisbane’s history. With compassion and respect, these works tell the stories of women who suffered institutional abuse at Goodna’s Wolston Park psychiatric facility, and Wallace focuses on their hard-won resilience while demanding that we not look away.

Anne Wallace

Contemporary Australian painter Anne Wallace is widely admired for her strange and suspenseful dream-like scenes. Her landscapes, cityscapes and interiors are made rich with particulars and always meticulously rendered. Circumstantial details — decor and architectural forms, outfits and poses that portray a mid-century glamour — are used to brush out a veneer of normalcy, yet underlying neuroses and more dramatic conflicts still haunt each scene — some so violent that they rupture the pristine surface with their terror.

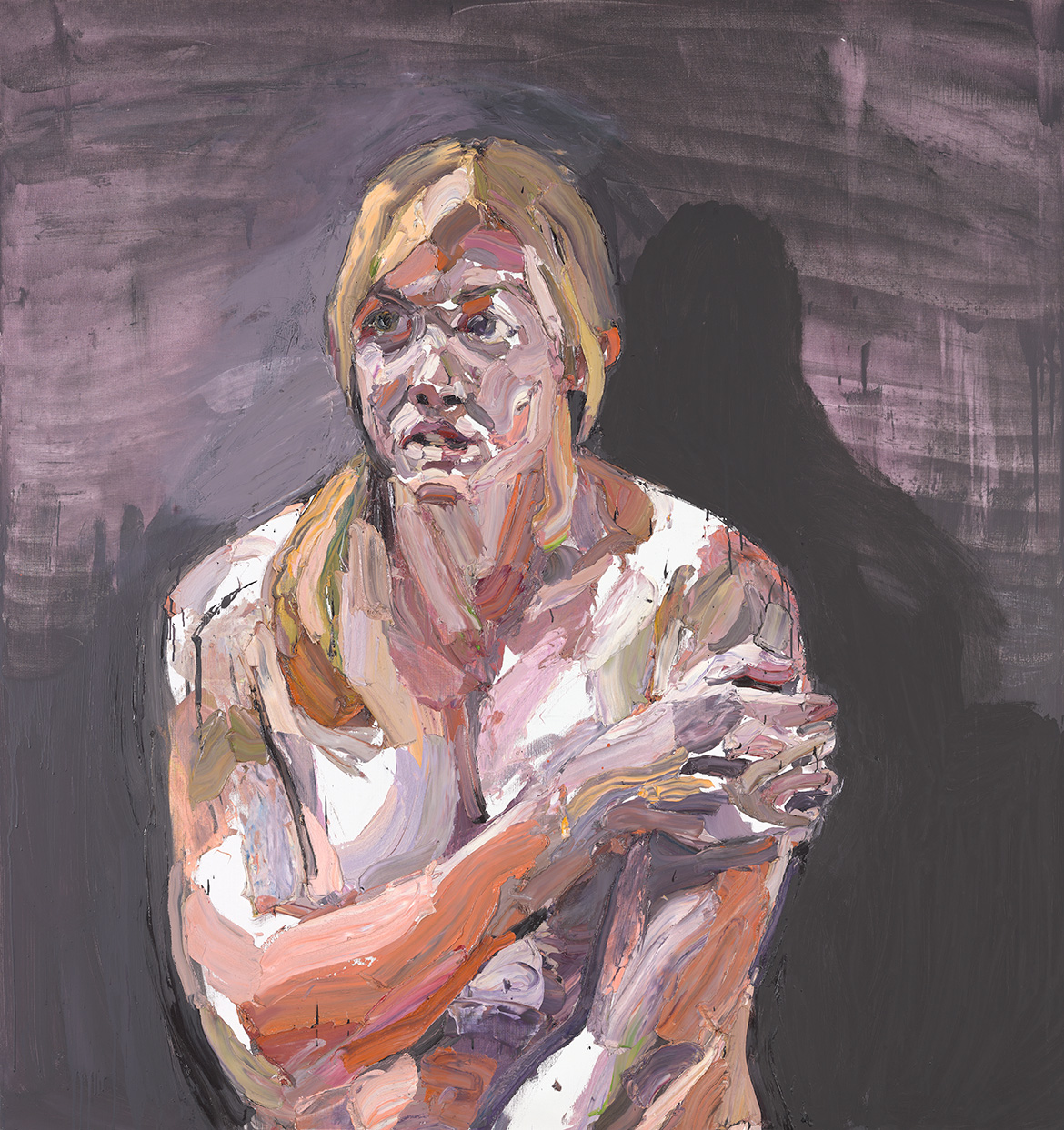

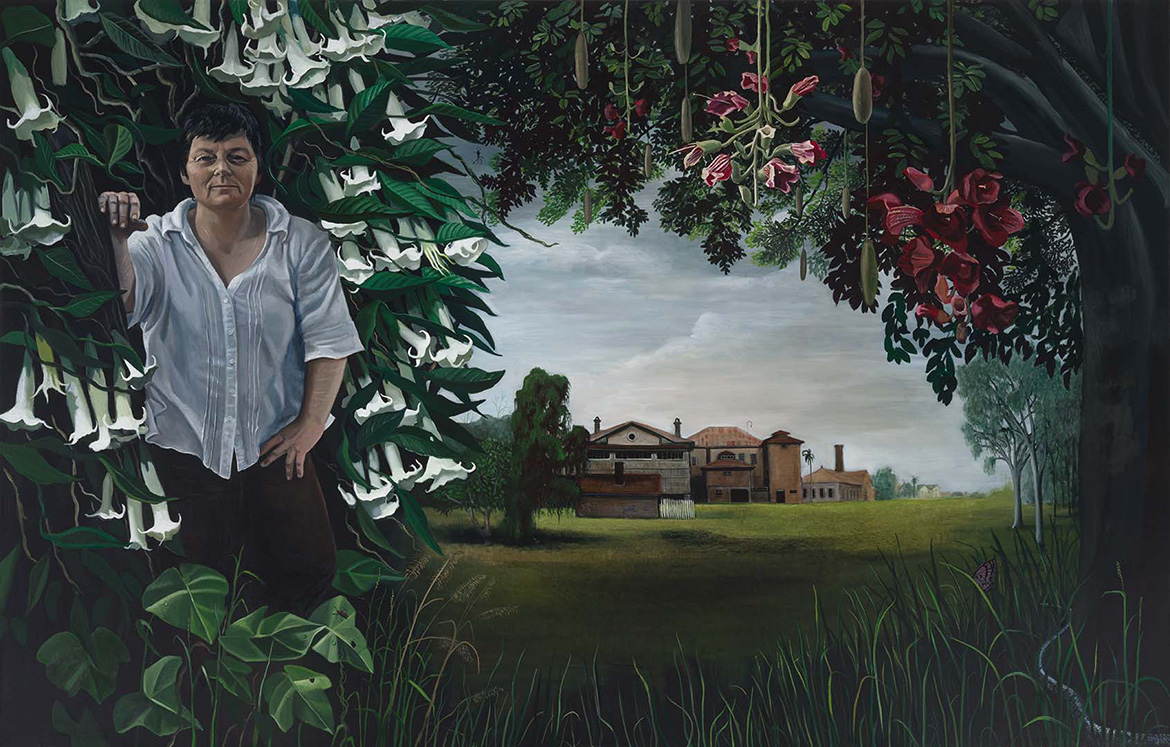

Anne Wallace ‘Portrait of Sue Treweek’

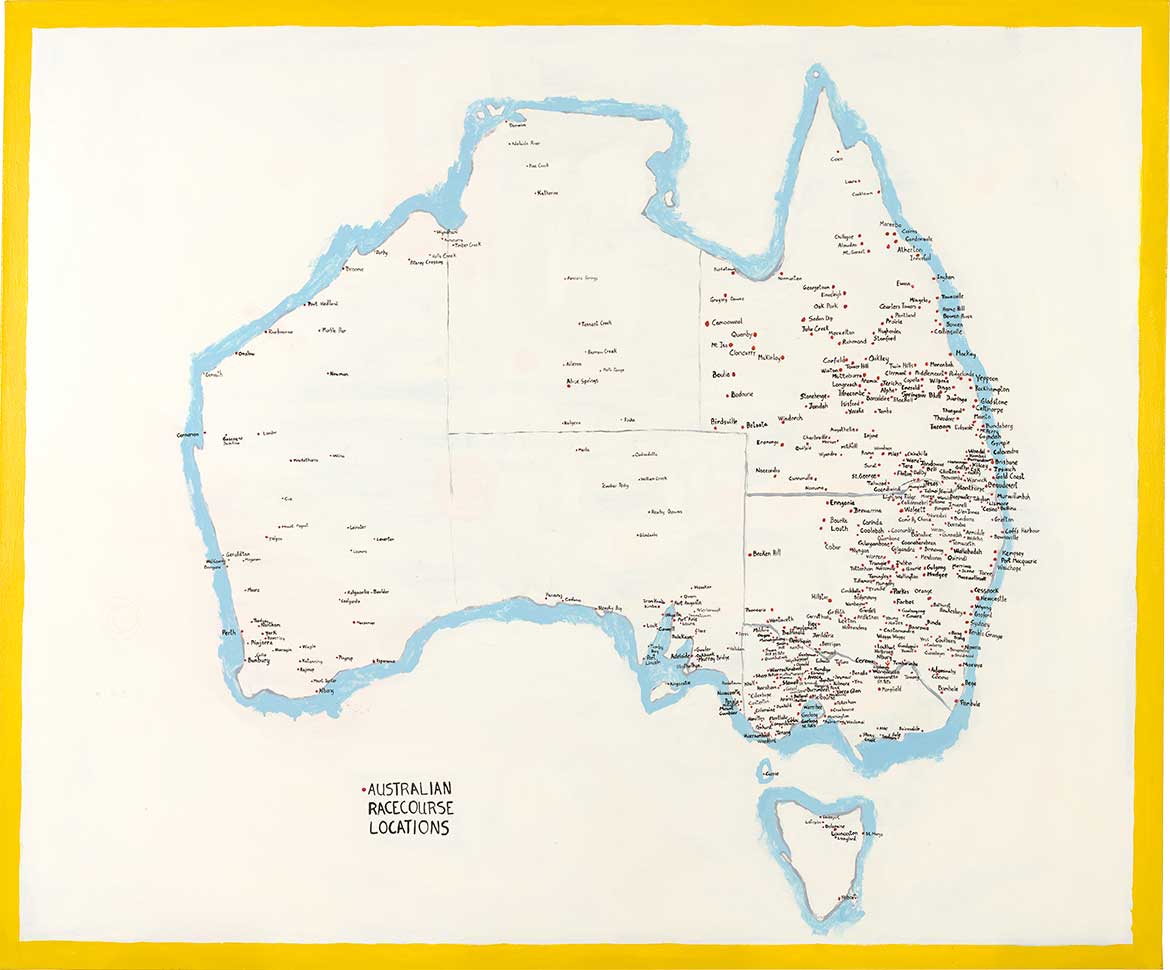

Portrait of Sue Treweek 2013 (illustrated) and Passing the River at Woogaroo Reach 2015 (illustrated) are the product of a converging series of events centred around Wolston Park, a Queensland psychiatric hospital that opened in 1865. Now known as The Park Centre for Mental Health, it remains a secure psychiatric facility today, although many areas have been decommissioned and new facilities built over the years. The institution has a chequered history, with instances of abuse, inappropriate treatment and insufficient accommodations marring the facility from its establishment. As insights into medicine and mental health have evolved, so too has the care and treatment offered, though stories of the institution’s unequivocal failings are still within living memory.

Abandoned Wolston Park buildings

Wallace has maintained an interest in Wolston Park (commonly referred to as ‘Goodna’) from a young age. She grew up in Brisbane and later studied at both the Queensland University of Technology and the University of Queensland. Long preoccupied by the history of psychiatry and divergent mental states, including its links to creativity, Wallace would return to the site numerous times over the years out of curiosity and for research. After experiencing post-natal depression, however, the character of these visits changed profoundly:

I knew that I might very easily have ended up there had I been born a bit earlier. In fact, for a period of a few months, I found myself going to the place and just looking at it through the windows of my car as some kind of compulsion . . . I eventually took a tour of it thanks to a psychiatrist friend who had worked there as a young doctor.1

Pursuing her interest, now with this more personal frame of reference, Wallace met former patient and advocate Sue Treweek after learning of her story through the Museum of Brisbane’s social history exhibition ‘Remembering Goodna’ in 2007. As a child, Treweek became a ward of the state after being misdiagnosed as ‘retarded’ for rocking herself to sleep. She was subsequently housed with adults in the Forensic unit where she was vulnerable to, and suffered, extraordinary abuse. Between the 1950s and 80s, there were up to 60 cases of children being inappropriately detained under similarly spurious diagnoses and exposed to the horrors of torture, sexual assault, isolation and humiliation.2

Years later, Wallace’s Portrait of Sue Treweek is a picture of endurance, strength and dignity — both artist and subject demand our pause. With the centre’s administration building behind her to the right, Treweek looks the viewer square in the eye. She is surrounded by the powerful and deadly hallucinogen known as the angel’s trumpet, a symbol of Wolston Park’s poisonous past.

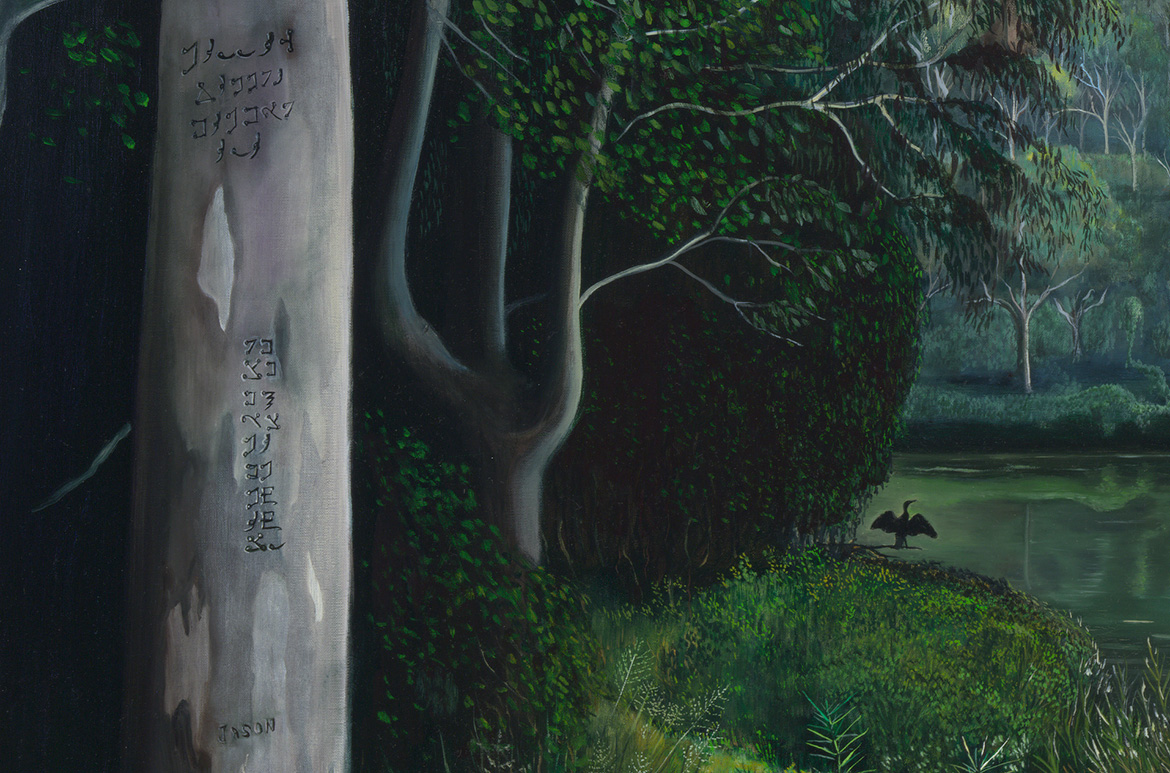

Anne Wallace ‘Passing the River at Woogaroo Reach’

Through Treweek, Wallace later met other survivors: Nell, Angela, Patty, Barbara L, Rhonda, Sandra, Pamela and Barbara S.3 These connections became the impetus for Passing the River at Woogaroo Reach 2015. The painting depicts a group of nine women — now adults, two in wheelchairs — adrift on a small boat on the river outside Wolston Park. The river banks are wildly overgrown, and a snake scurrying with an egg in its mouth symbolises the theft of their youth and innocence. A torn mattress in the thicket to the right is emblematic of the State’s failure to prepare the women for life outside the institution and to provide them with the means to live in the real world.

On the left, a tree trunk shows the carved initials of each woman, but Wallace has chosen to write these in an occult alphabet known as ‘passing the river’ to draw attention to the obfuscation and misunderstanding that they confronted when sharing their experiences of being institutionalised. In October 2017, after years of persistence, Treweek and the other survivors in Wallace’s painting were finally offered compensation from the Queensland Government for their grievous mistreatment.4

While these two works are somewhat aside from the mainstay of Wallace’s practice in their reportage qualities, as an artist she is uniquely positioned to bring a compassionate and respectful awareness to this dark chapter in Brisbane’s history. By framing each composition with shadowy vegetation, she reminds us of the dangers that lie in wait for the vulnerable in places hidden from view, especially when society collectively averts its gaze from truth and decency. Wallace addresses this appalling and lingering injustice without sentimentality or sensationalism while focusing on the women’s hard-won resilience.

Peter McKay is Curatorial Manager, Australian Art, QAGOMA

Endnotes

1 Email from the artist to Simon Elliott, 20 February 2018.

2 Joshua Robertson, ‘“It’s been such a battle”: Wolston Park survivors win shock payouts’, The Guardian, 19 October 2017, <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2017/oct/19/its-been-such-a-battlewolston-park-survivors-win-shock-payouts>, viewed March 2019.

3 Artist statement, June 2017, <https://www.qmhc.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/anne_wallace_artist_statement.pdf>, viewed March 2019.

4 Robertson, ‘“It’s been such a battle”’.

In conversation: Anne Wallace and Sue Treweek

In conversation: Anne Wallace

Featured image detail: Anne Wallace Passing the River at Woogaroo Reach 2015

#QAGOMA