Live Music & Film returns to the Australian Cinémathèque, GOMA at 11am on Sunday 25 February 2024 with the joyous Man with a Movie Camera 1929 and a live score played on stage by Jonny Ng from Camerata — Queensland’s Chamber Orchestra.

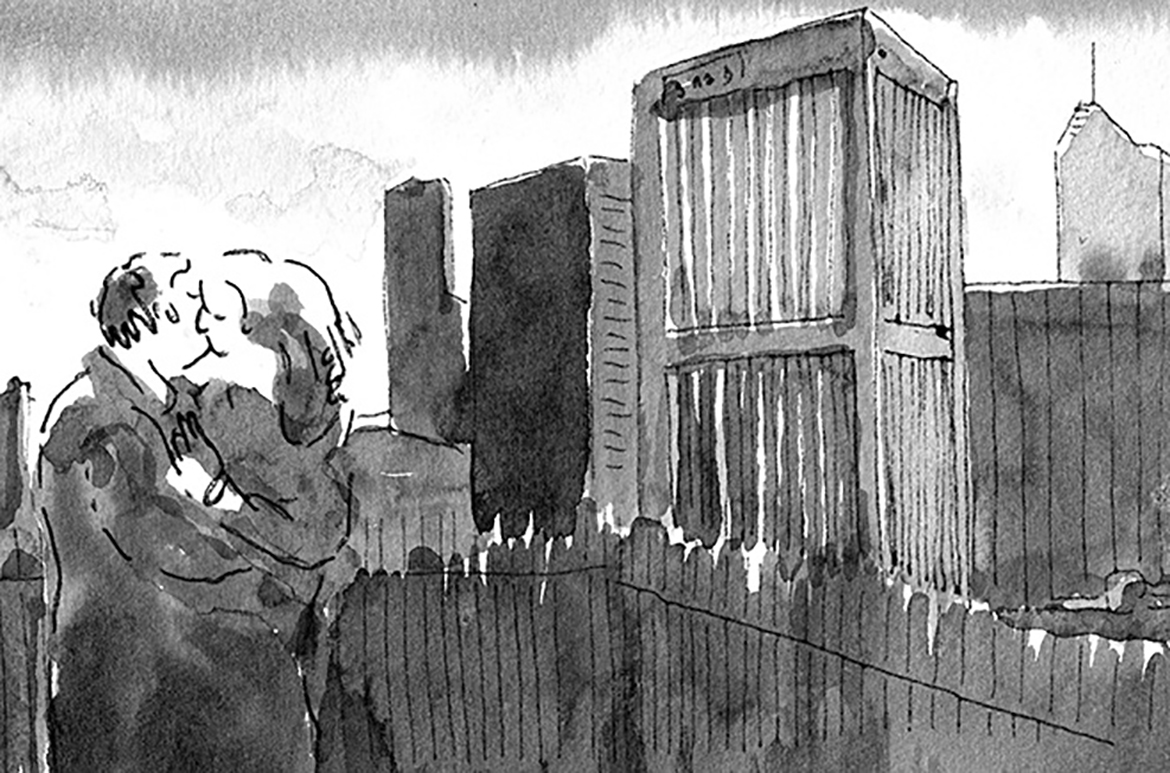

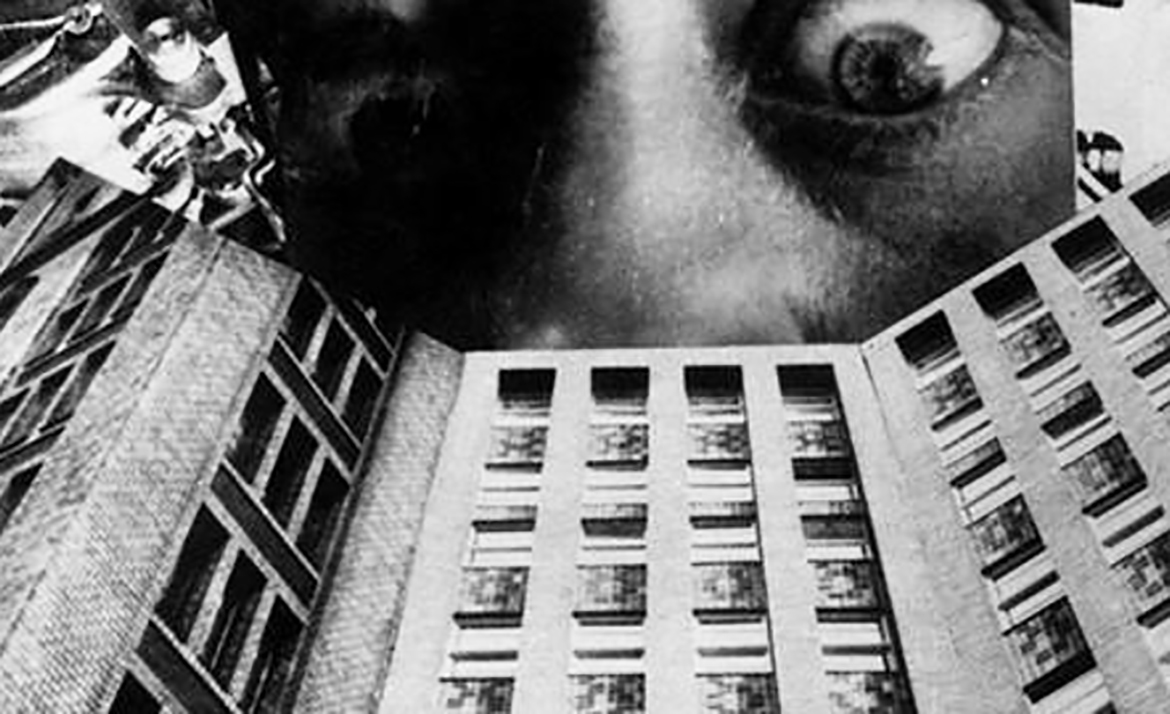

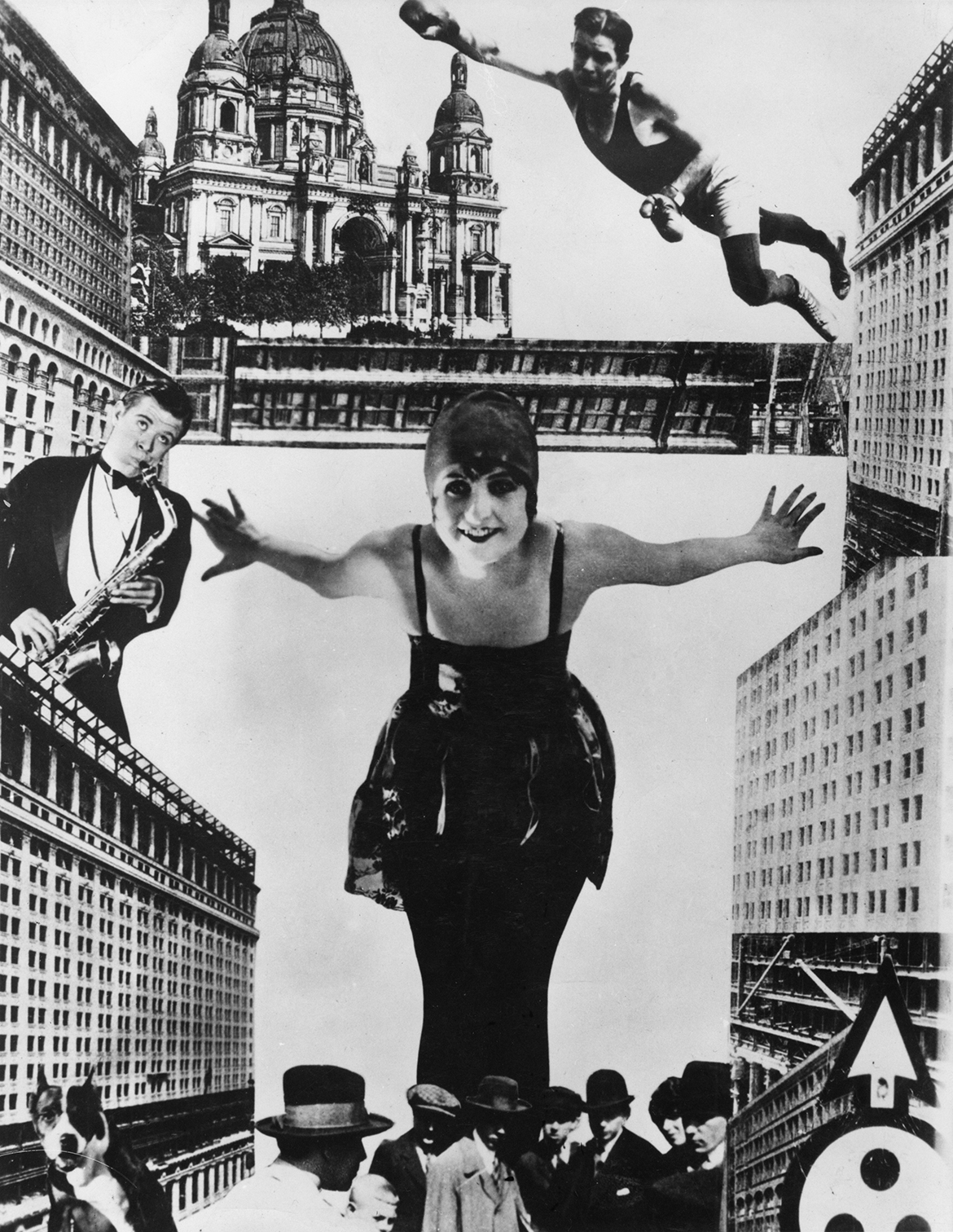

Shot by a Polish filmmaker in Moscow as well as Odesa and Kyiv (both then in the USSR, now in Ukraine), the film was initially labelled ‘cine-hooliganism’ for its bold filmmaking. Man with a Movie Camera delights in the possibilities of cinema, embracing the roles played by those making the films as much as those in front of the lens. The cameraman is celebrated as a heroic innovator, who daringly shoots from the top of a moving train or cranks the camera while riding in an open-top car capturing the traffic and the people travelling around him.

Our musician Jonny has crafted his live score which, like all our performances, will be partly improvised and partly pre-prepared. We asked him about the film and the music he’s planning to play.

Get tickets Man with a Movie Camera

Australian Cinémathèque, GOMA

11.00am, Sunday 25 February 2024

Rosie Hays / What were your first impressions of the film ‘Man with a Movie Camera’ and what did it inspire?

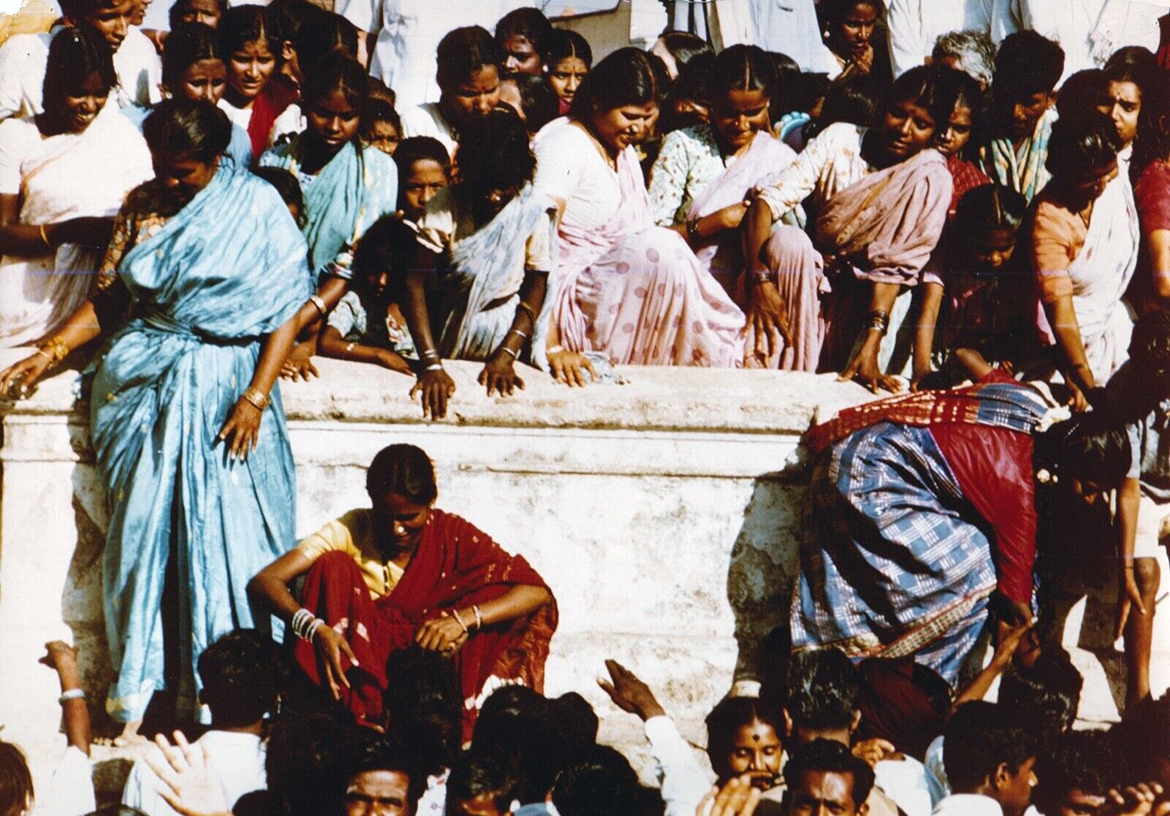

Jonny Ng / Man With A Movie Camera was truly captivating on first watch. I marvelled at the technical skill and artistry that went into its creation and found the experience a joyous one, a celebration of everyday life and a glimpse into a window of time in history. Although filmed in Soviet Russia a century ago, it was intriguing how relevant and relatable this film is now and how Dziga Vertov had such a masterful eye to provide such timeless insight into humanity. There are some very poignant moments scattered throughout the film, for example one scene cuts between a couple getting married, a woman giving birth, and a funeral procession. There was also at times an enigmatic feeling I got from the film which I hope to explore in my musical response.

Rosie Hays / What kind of mood should the audience expect for your live score and what music and / or instruments can the audience expect for this performance?

Jonny Ng / I aim to capture the energy of the film through a mix of Russian folk music, cinematic soundscapes and minimalism, and of course Russian Soviet music from the time of the film. The mood will primarily be passionate and joyful but will also flicker between being reflective, darkly chromatic, and wistful. In addition to playing violin, viola, and piano live, all other music will be recorded by me on piano, violin, viola, cello, double bass, percussion instruments, as well as other peculiar items from around the house like a biscuit tin, Lindt bunny bells, my mobile phone, kitchen utensils. I will also be using prepared piano to add further texture and percussive effects to the score.

Rosie Hays / Did you watch the film with its soundtrack, or do you prefer to encounter it without sound when you start to think about what music you’ll make?

Jonny Ng / Watching the film in its original silent form was important to me. I wanted the first viewing to be unadulterated which would allow for musical ideas to form in my head while experiencing the film. I also find that music in a film can at times be quite distracting as I am always instantly drawn to the music and trained to actively listen with a critical ear so I wanted to eliminate that distraction. I also wanted to be free from influence of other musical interpretations of the film so the final result was more authentically my response.

Rosie Hays / In your role as Principal 2nd Violin with Camerata – Queensland’s Chamber Orchestra, you’ve previously performed live scores for films. Is this process for ‘Man With a Movie Camera’ similar or quite different? What’s your approach to crafting a musical response to a film?

Jonny Ng / The process is very similar here but the only difference is that I am responding to the entirety of the film. In past responses with my Camerata colleagues, we have very democratically divided up the response in equal portions of the film which we were able to stitch together to create a beautifully cohesive score. This film does have 6 very distinct sections which helps make the process easier. I first noted down what I thought was the general feeling or mood of each section. Then, I flagged specific scenes throughout the film that elicited strong responses in me so I can try and highlight these moments with my musical choices. I have a long list of existing compositions that I feel could marry well with the film so it will be a delightful puzzle of mixing and matching parts of these works with my own composition and improvised music. I will be sat at the piano with violin and viola at the ready and play while I am watching the film to see what works.

Rosie Hays / You’ve mentioned in a previous interview that music gives us the ability to connect with people as well as greater empathy and sensitivity to emotions. ‘Man With a Movie Camera’ strikes me as a film that is very interested in the human condition and perhaps has almost an awe for the capabilities of humanity. I’m curious to know if you intend to heighten audience sensitivity or build empathy with a particular aspect of the film.

Jonny Ng / Music has the power to cross boundaries, to create change, to build community, to endure and it is my belief that music is an art form that represents humanity distilled into its essence. So, I really hope that I am able to add to the audience experience of this enduring film and provide a unique interpretation of it through my own lens.

Rosie Hays is Associate Curator, Australian Cinémathèque, QAGOMA

The Australian Cinémathèque

The Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) is the only Australian art gallery with purpose-built facilities dedicated to film and the moving image. The Australian Cinémathèque at GOMA provides an ongoing program of film and video that you’re unlikely to see elsewhere, offering a rich and diverse experience of the moving image, showcasing the work of influential filmmakers and international cinema, rare 35mm prints, recent restorations and silent films with live musical accompaniment by local musicians or on the Gallery’s Wurlitzer organ originally installed in Brisbane’s Regent Theatre in November 1929.

Featured image: (left) Production still from Man with a Movie Camera 1929; Director: Dziga Vertov / (right) Jonny Ng; Photograph: Morgan Roberts, courtesy of Camerata, Queensland’s Chamber Orchestra

#QAGOMA