Passionate and rebellious, Helge John ‘Jon’ Molvig (1923–70) was a relentless artistic innovator, who, in the 1950s and 1960s, attained national recognition.

Newcastle-born, Molvig moved to Brisbane in 1955 and dominated the city’s art scene until his death just before he turned 47. With great energy, he created figure studies, portraits and landscapes, making radical stylistic shifts to suit his subject matter. Brisbane inspired Molvig’s greatest work, and it was from here that his influence spread.

On his return to Australia after serving overseas in World War Two, he studied art at East Sydney Technical College (1947–49). He then travelled throughout Europe until 1952, where he was influenced by the work of the German and Norwegian expressionists. By 1956, his unique brand of raw figuration was gaining prominence for its painterly intensity.

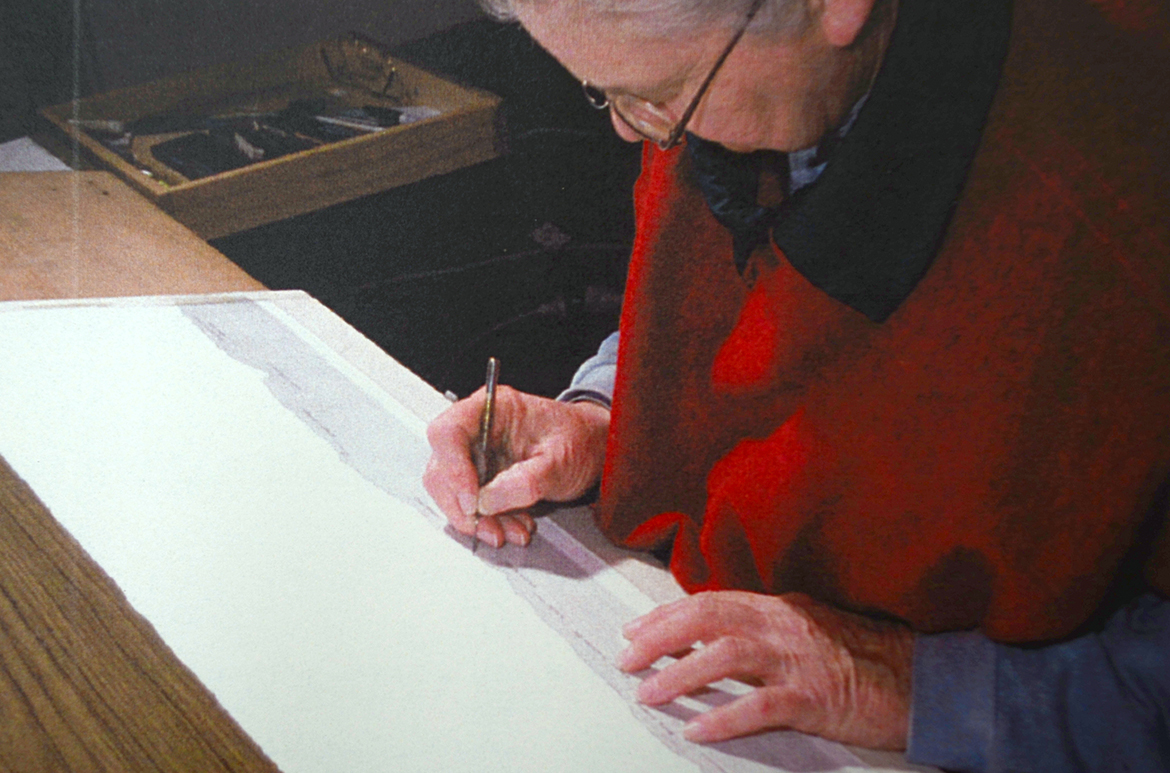

Molvig’s work is underpinned by superb draftsmanship and a commitment to the art of painting – a passion that inspired countless students in the late 1950s at his teaching studio at St Mary’s Anglican Church, Kangaroo Point, and Corroboree House, Spring Hill.

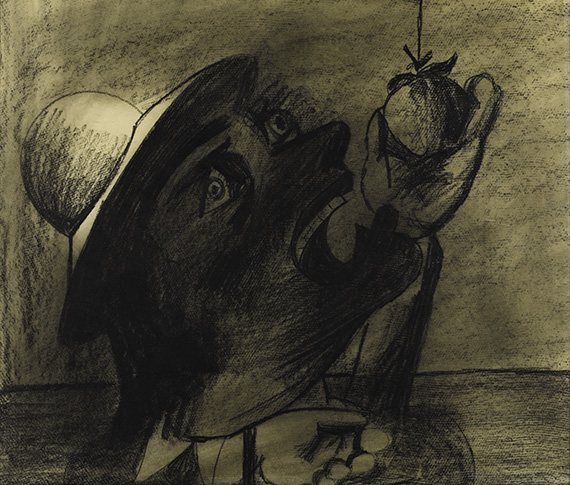

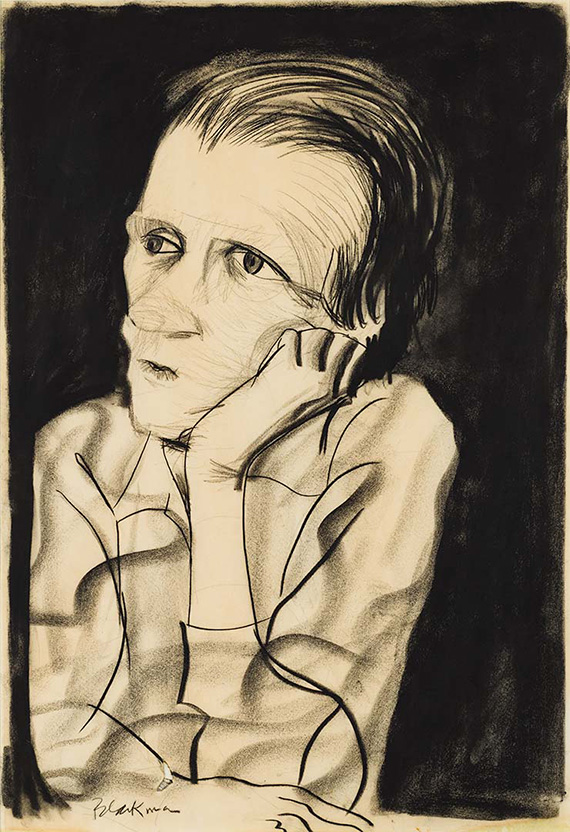

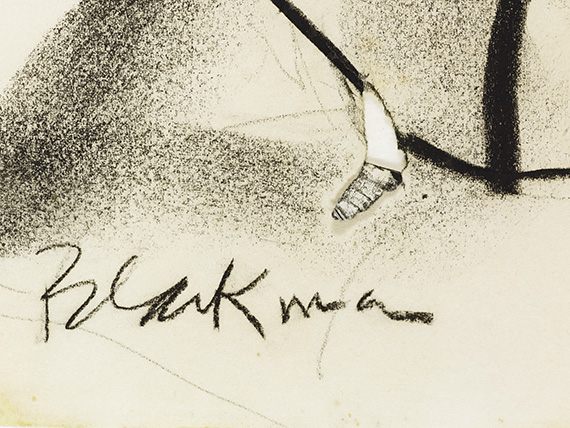

Jon Molvig Archibald winning portrait ‘Charles Blackman’

Molvig entered the Archibald Prize 13 times between 1952 and 1966, before winning with his portrait of artist–friend Charles Blackman. Reviewers proposed that Molvig merited the win on many prior occasions, to which the artist cynically responded: ‘the best portraits don’t win the Archibald’.

From the late 1960s, Molvig’s health began to fail, and he died in May 1970 soon after his body rejected a kidney transplant.

In her 1984 biography Molvig: The Lost Antipodean, Betty Churcher eloquently summarised Jon Molvig’s complex life and significant contribution to Australian art:

Because he has been so difficult to categorise, Molvig has often been overlooked by historians and curators . . . Yet, at the full stretch of his talent, he has produced images so powerful and urgent that they have that quality of all good art: they remain in the mind in all their original clarity.

RELATED: Jon Molvig: The power of expression

Challenges and discoveries

A maverick by nature, Molvig’s practice reflects his enthusiasm for experimentation, in which he stretched the capability of a diverse range of materials.

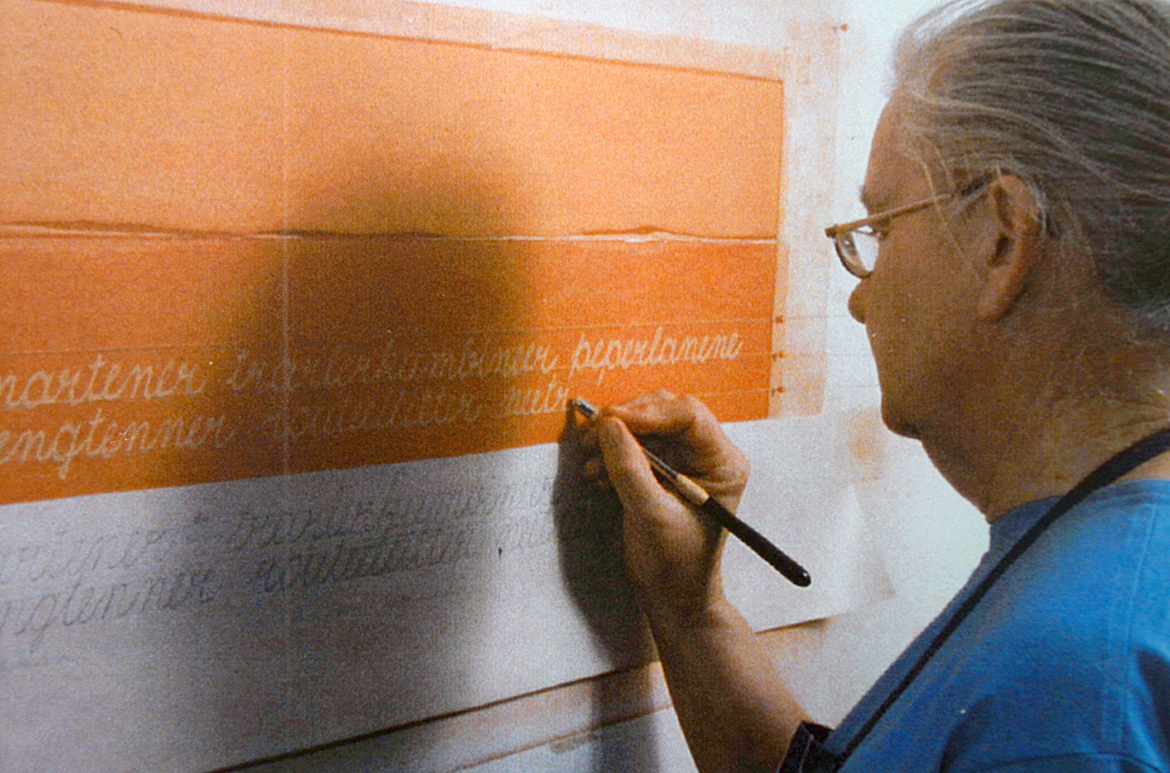

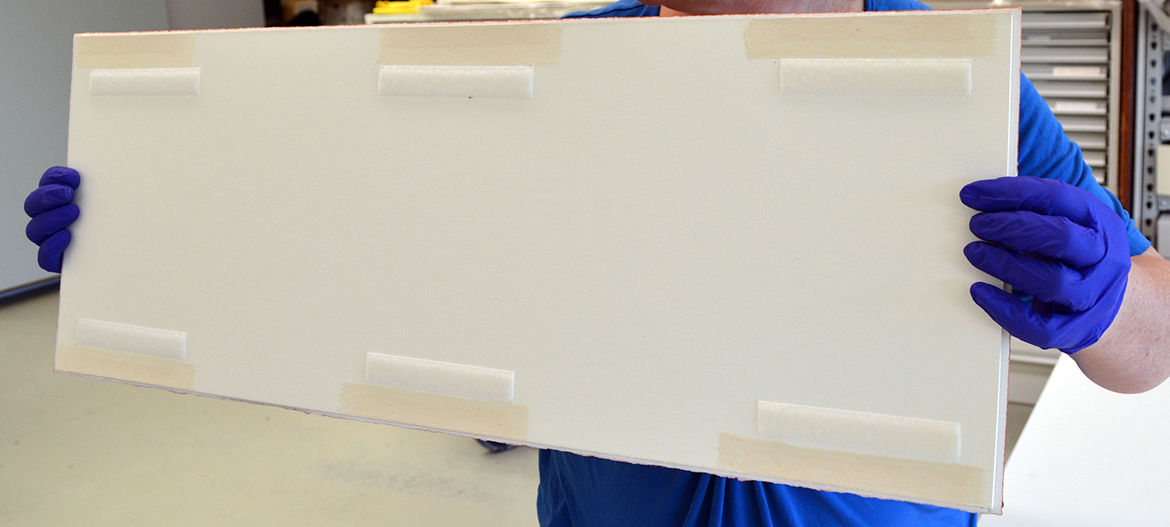

Before the treatment of any works on paper, we undertake extensive testing to determine the solubility of the degradation, and tailor a conservation rigid gel with customised reagents to address the needs of each artwork. These customised gels act as molecular sponges which, when placed in contact with the artwork, allow control of moisture within the paper. They efficiently target and make soluble staining and discolouration, drawing out and trapping it in the gel. As a result, these treated works have been improved both visually and physically; the original colour balance has been restored, and the artwork is stabilised so it can be appreciated long into the future.

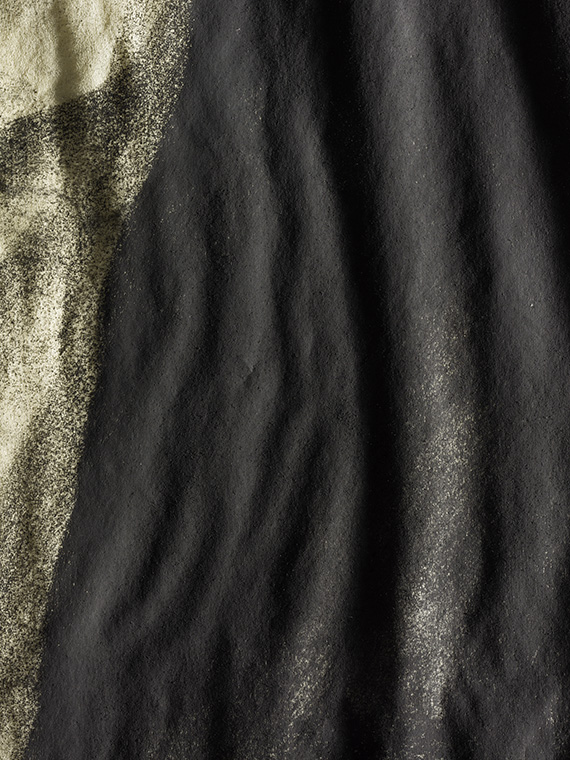

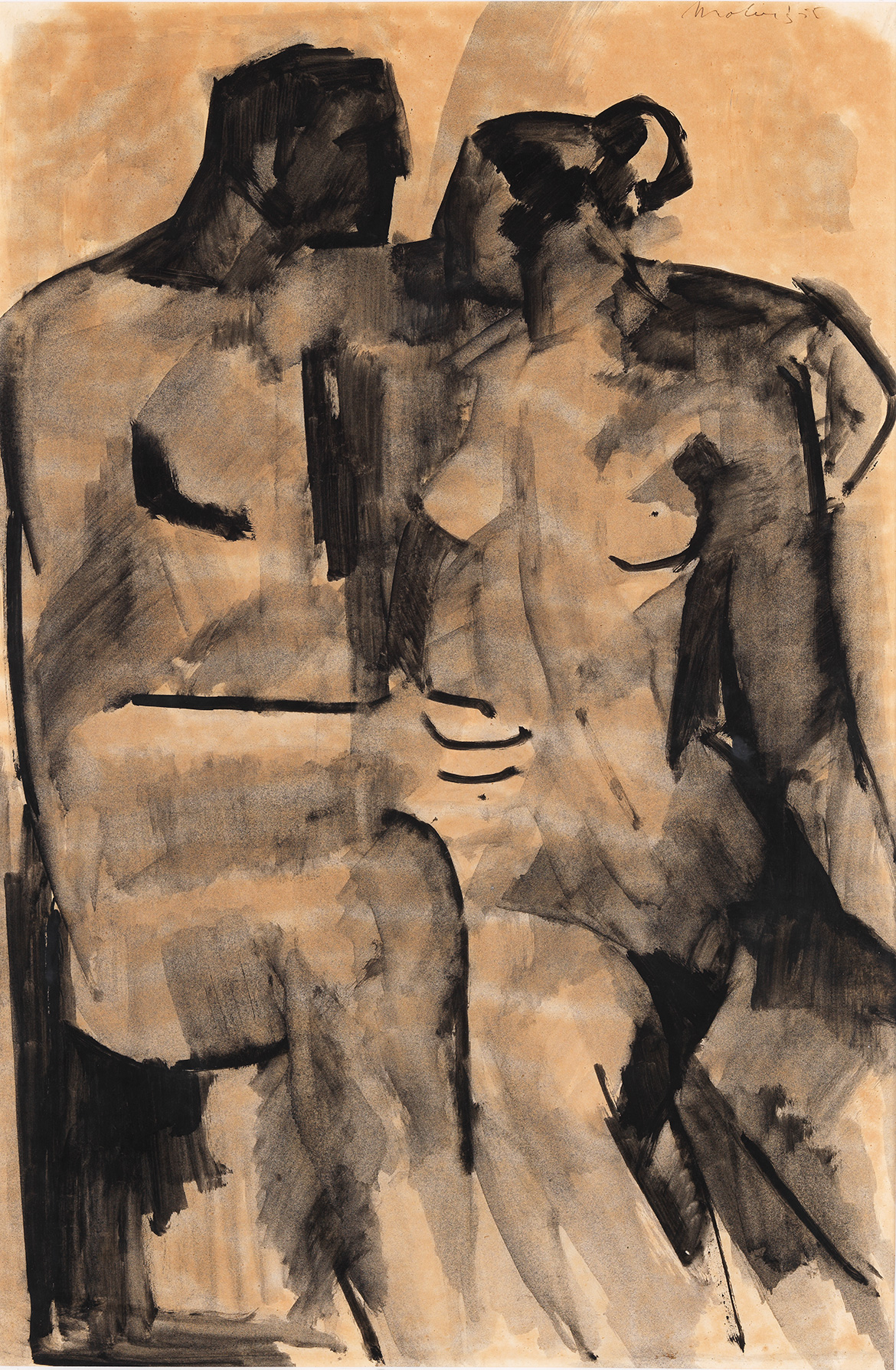

Jon Molvig ‘The lovers’: Before conservation

Jon Molvig ‘The lovers’: After conservation

Behind-the-scenes

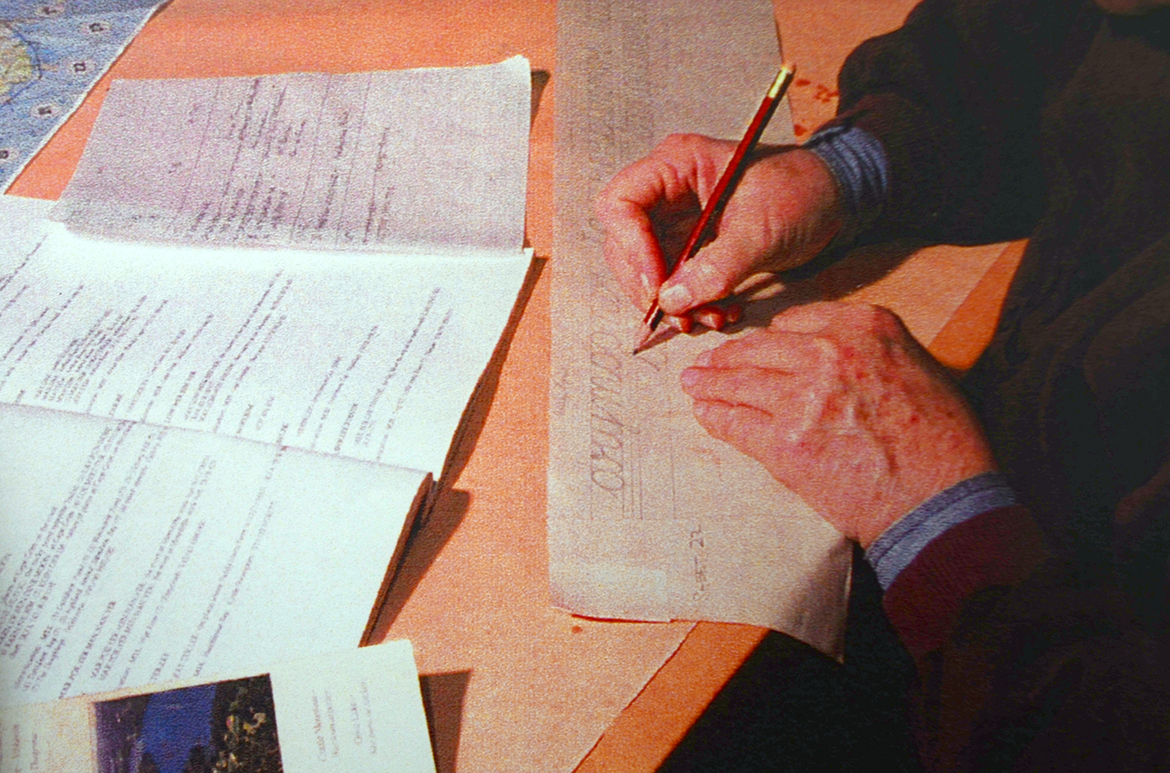

Samantha Shellard, Works on Paper Conservator and Adele Barbara, Paper Conservation Intern, share insights into using conservation gel technology to treat The lovers 1955 a brush and ink work on paper on hardboard. This large work bears the hallmarks of Molvig’s fruitful period in Brisbane, the brushwork is distinctive, looping strands of ink contain the composition giving a feeling of spontaneity that belies the carefully considered creative process.

The lovers had extensive deterioration consisting of distracting bands of dark discolouration. This deterioration resembled zebra striping across the couple, compromising the artist’s original intent by obscuring details and fine brushwork. Using a customised gel sheet slightly larger than the artwork meant that the disfiguring staining could be removed uniformly across the entire surface, which significantly improved the visual appearance of the work.

After treatment, The lovers is visually and physically improved, the original colour balance is restored and the artwork is stabilised so it can be appreciated into the future.

In order to be a good painter in any field, it doesn’t matter whether it is non-objective painting or abstract painting or figurative painting, you certainly must be able to appreciate and understand line and tension, tone, and be able to put it down accurately as a draughtsman does. Jon Molvig

Jon Molvig ‘Windows’

One of greatest challenges was Windows 1951, a bright, primary-coloured artwork, which had an ugly grey fungal accretion covering almost a third of the surface area, predominantly throughout the large mottled blue rectangular section on the right-hand side.

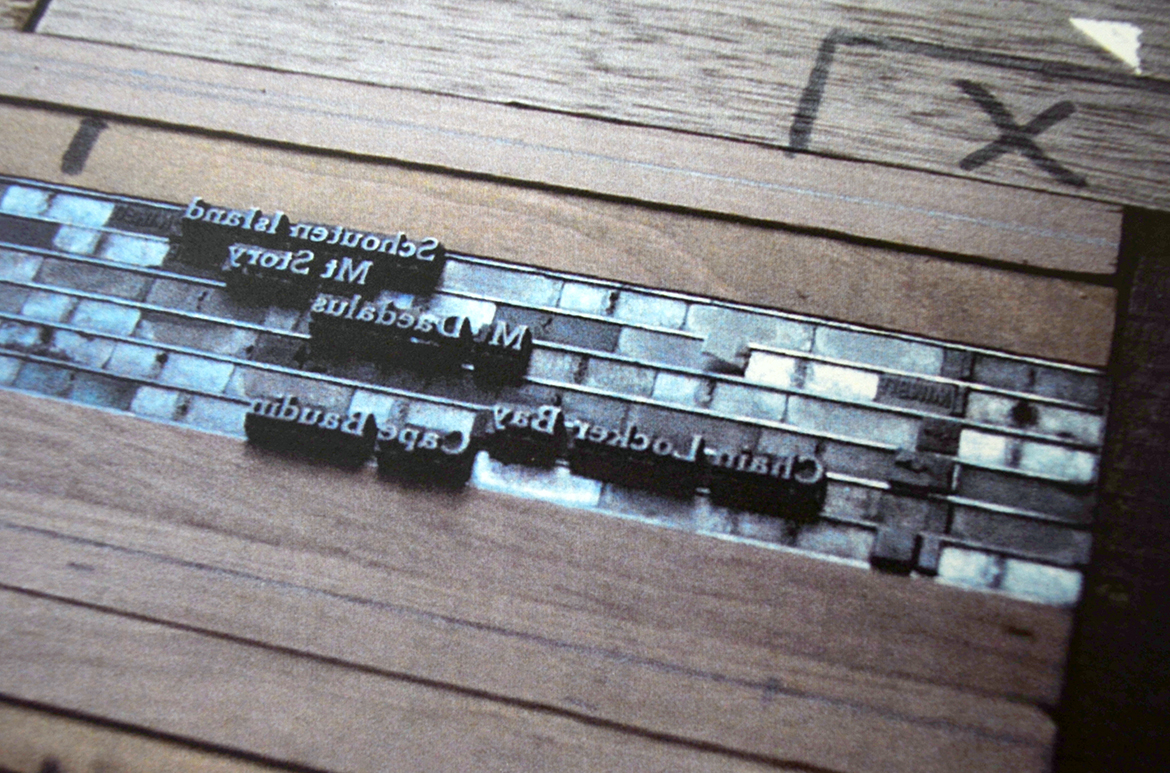

This artwork was previously described as a gouache on cardboard. However, it was not until samples of both the accretion and blue paint, taken from different locations within the large blue building, were analysed using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) that suspicions were raised about its complex surface. The results revealed that this area was actually mixed media — there was evidence of gum Arabic binder, which is present in gouaches and watercolours, but there were also resin components that are found in oil paints.

The blue surface was literally a patchwork of different paint layers. After comprehensive testing and analysis of the fungal accretion, we devised a cleaning method that involved applying an isolating silicon solvent mask to protect the underlying gouache paint layer. We then applied a viscous gel containing reagents, which softened the accumulated accretion and drew it up from the surface of the work into the gel by capillary action.

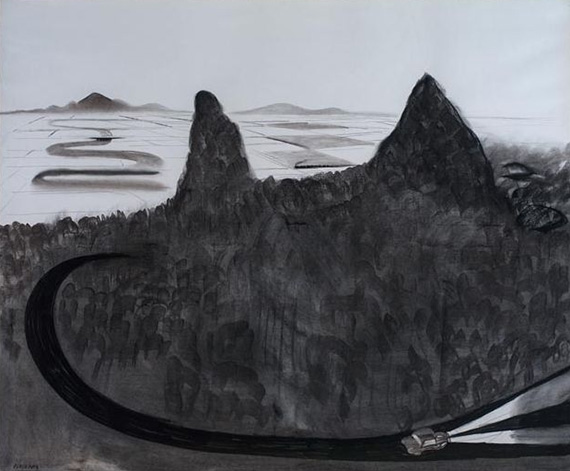

Jon Molvig ‘Burnt landscape’

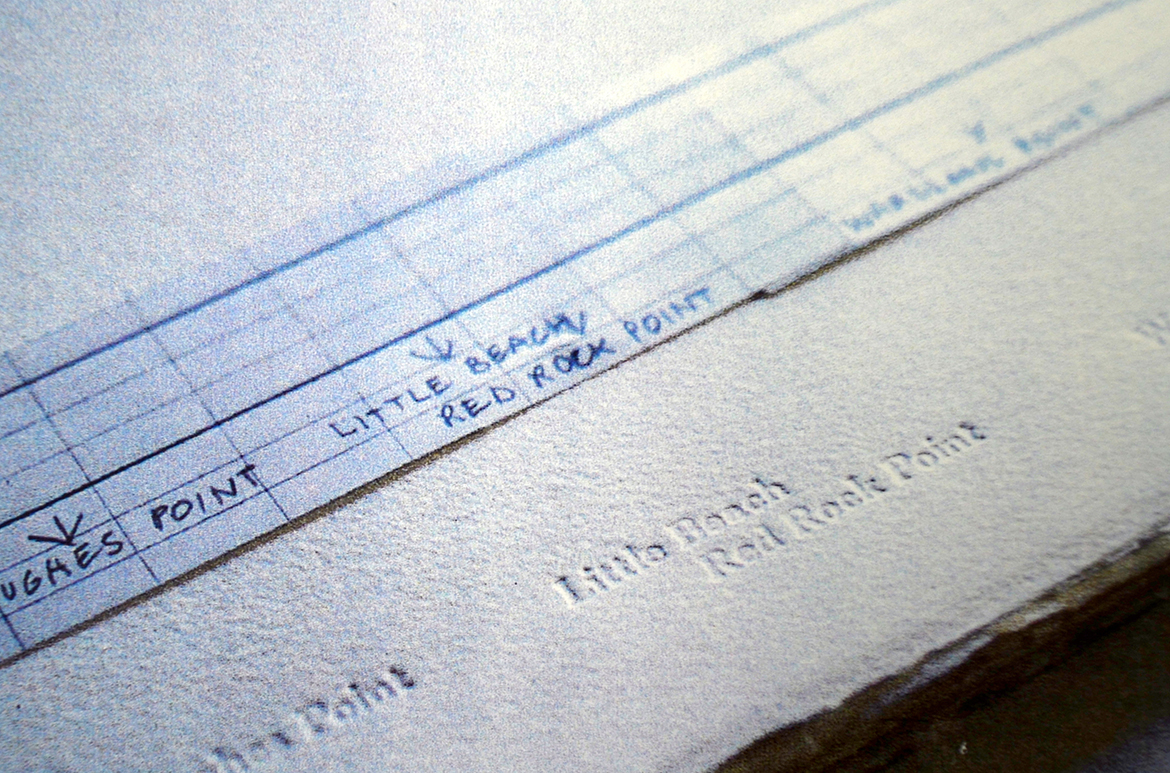

The conservation of Burnt landscape no.1 (After the fire) 1953 required a collaboration between painting and paper conservators, which resulted in the discovery of Molvig’s signature in the lower right-hand corner of the work, previously camouflaged by the old mounting. Layers of brown gummed tape had obscured it, as well as hiding compositional features from the perimeter of the work. This tape was painstakingly removed from all four edges of the work using humidification and an application of a gel poultice, with the residual adhesive removed in a separate procedure.

While these treatments were happening, our conservation framing team worked with curators to research frame mouldings from the period, and recreated profiles to complement the muted tones of the artist’s works. These conserved works are part of the ‘Jon Molvig: Maverick’ exhibition at the Queensland Art Gallery

Samantha Shellard is Conservator (Works on Paper) and Adele Barbara was paper conservation intern from January to September 2019. Jointly they presented ‘Challenges and Discoveries — utilising conservation gels to treat works on paper by Jon Molvig’ at the New Zealand Conservators of Cultural Materials (NZCCM) Conference on Modern & Contemporary Materials: Research, Treatment and Practice, 23–25 October 2019, at Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhettu.

Buy the publication

Jon Molvig: Maverick explores Molvig’s contribution to the Brisbane art community, highlights his stylistic eclecticism, and revalues his unique contribution to art history. This richly illustrated, hardcover publication is available from the QAGOMA Store and online.

The QAGOMA Foundation has supported this conservation project investigating Jon Molvig’s working methods and the treatment of his works on paper in the Gallery’s Collection.

Feature image detail: Jon Molvig The lovers 1955

#QAGOMA