Opening this week is the landmark film program ‘The Last of England: Thatcherism and British Cinema’. The free program begins with a special 20th anniversary retrospective of films by the acclaimed artist and filmmaker Derek Jarman. This major survey of British cinema continues at the Gallery’s Australian Cinémathèque, GOMA until the 25 June 2014.

We are all accomplices in the dream world of soul; it is not just personal, it’s general, we make these connections all the time. As Heraclitus said: ‘Those who dream are co-authors of what happens in the world’. Derek Jarman, Kicking The Pricks, 1996:108

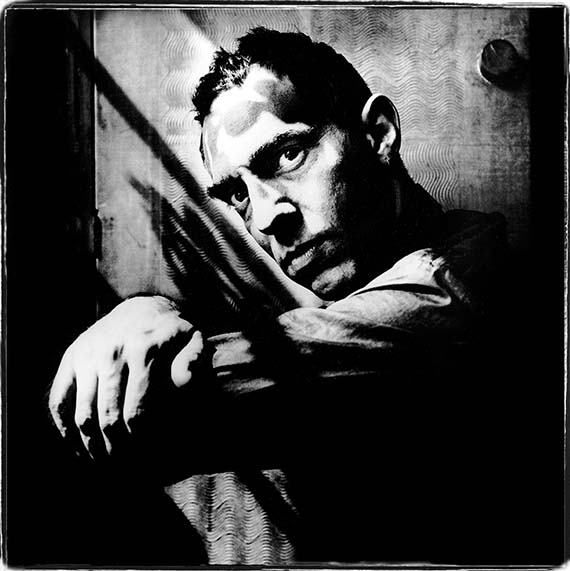

Derek Jarman (1942–1994) is Britain’s most singular director and one of the most compelling artists to explore the moving image. In his short but expansive career, he completed 11 feature films that eschew conventional narrative and more than 60 Super-8 and 16mm montage films. His cinema tackled subjects of sexuality, history and politics without compromise and considered the creative process itself with a deeply affecting sensibility. In addition to his work in theatre and cinema, Jarman maintained his practice as a painter, wrote a series of memoirs and diaries, made music videos and was a passionate gardener. Twenty years after his death from AIDS-related conditions, his films, writing and paintings constitute more than ever, a vital statement against cultural conservatism and the will to be a self-determining artist.

Jarman studied painting at Kings College London and at the Slade School of Art and saw filmmaking as another form of painting. He applied his skills and interest in theatre and architecture to his role as production designer for Ken Russell’s films The Devils 1971 and Savage Messiah 1972, as well the Royal Ballet’s production of Jazz Calendar 1968. These experiences alongside his interaction with London’s gay social milieu gave him the confidence to begin developing his own projects and some of the first truly independent British features. While his filmography attests to a strong personal vision, Jarman also valued the collaborative process over individual control. Throughout his career he worked with a key group of creative collaborators, including producer James Mackay, actress Tilda Swinton, production designer Christopher Hobbs, composer Simon Fischer Turner and costume designer Sandy Powell.

Working with limited resources from the late 1970s to early 1990s, Jarman developed a unique cinematographic practice that turned those restraints into a signature aesthetic – what he conceived as ‘a cinema of small gestures’. Jarman enjoyed the autonomy and portability of shooting with his Nizo 480 and Beaulieu Super-8 cameras and filmed at 3-6 frames per second (as opposed to the usual range of 16-24) to extend the duration of film stock. This made for a more economical shooting process as well as developing a visual language similar to stop-motion photography, wherein images appear suspended in time or flicker beyond comprehension. Jarman experimented with different approaches to re-filming the fragile Super-8 stock and with the aid of U-matic recording technology, developed film/video hybrids that celebrated a new vocabulary of ‘magic realism’ created with the effects of video compositing/superimpositions and editing, saturated colours, and an emphasis on the material quality of film and video stock.

After publically disclosing his status as HIV-positive in 1986, Jarman worked under the spectre of death, writing and directing with urgency. His work took on a political dimension, aimed at tackling the cultural reversals occurring in British society under Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government. While he would refer to himself as ‘small-c conservative’, desiring the age of Shakespeare to escape the plight of England, his strident politics were always on show and his artistic vision was nothing short of revolutionary. Jarman’s storytelling was anachronistic, connecting the historical and contemporary through costuming, staging and dialogue, and throughout his career he sought to connect aspects of his personal history with public history. Music journalist Jon Savage has commented that Jarman’s subversive statements about British society ‘gave both his life and work a sharpened focus’ and made him ‘a standard for those who every fibre revolted against the power politics of the early to mid-1980s.’

Never one to allow his personal and public life to diverge, Jarman was one of the few openly Queer filmmakers during his lifetime and was unapologetic about his quest to represent homosexuality onscreen. Taking cues from filmmakers Pier Paolo Pasolini and Rainer Werner Fassbinder, his films are dominated by stories of exiles and outsiders – from Saint Sebastian to William Shakespeare, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, Benjamin Britten, Wilfred Owen, Christopher Marlow and Ludwig Wittgenstein. Jarman’s project was to re-mythologise the importance of these homosexual artists, writers and intellectuals within cultural history and make visible through his work a strong Queer sensibility within the history of British art and film. Driven by the knowledge that his time was limited, Jarman was also an outspoken activist and used his life and work to negate the stigma associated with living with HIV and rally against the threat of Section 28, the 1988 British law introduced by Thatcher’s government that legislated against the promotion of homosexuality. He died of bronchial pneumonia shortly after his 52nd birthday on February 19, 1994. Jarman’s parting words in his last memoir At Your Own Risk: A Saint’s Testament (1993) read:

I am tired tonight. My eyes are out of focus, my body droops under the weight of the day, but as I leave you Queer lads let me leave you singing. I had to write of sad time as a witness ― not to cloud your smiles ― please read the cares of the world that I have locked in these pages; and after, put this book aside and love. May you of a better future, love without care and remember we loved too. As the shadows closed in, the stars came out. I am in love.