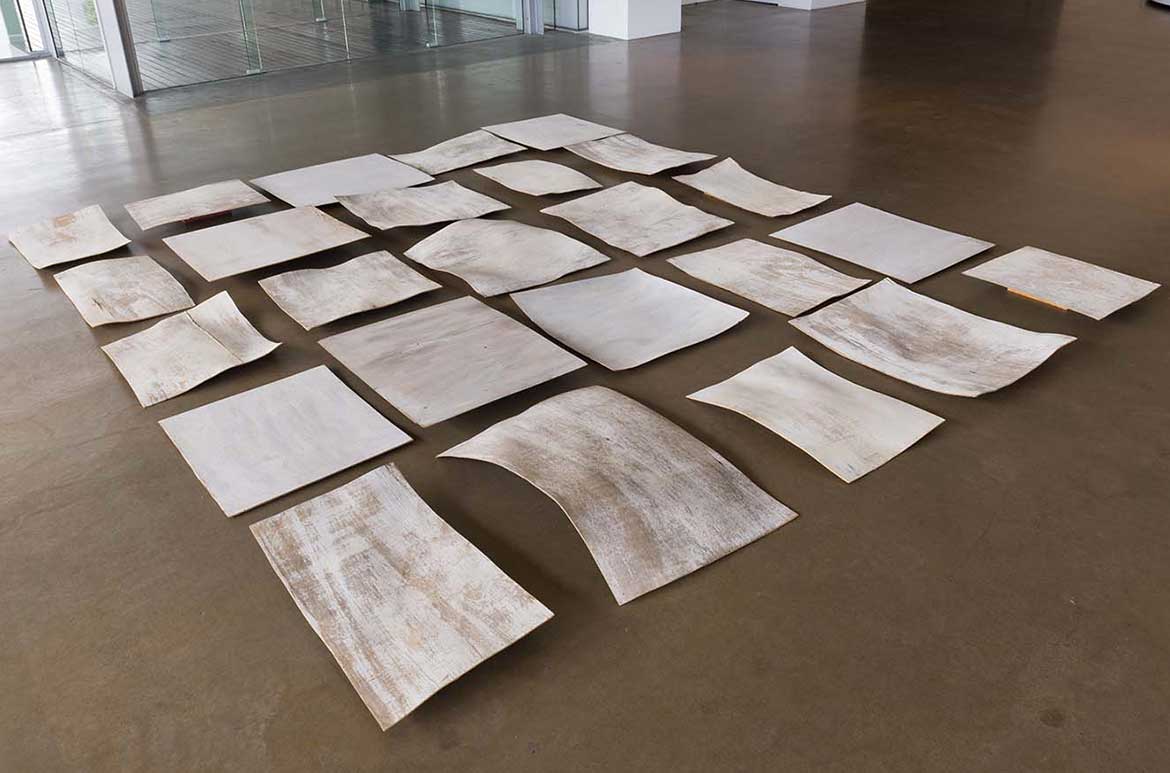

Overland, a wonderful work by Rosalie Gascoigne entered the Gallery’s collection as an exceptional gift, given in memory of Rosalie and Ben Gascoigne, her husband.

Gascoigne is among the most highly regarded Australian artists of recent history. Coming to art somewhat later in life — only holding her first exhibition in 1974 at the age of 57 — Gascoigne eschewed the dominant career pattern followed by most and walked a path of her own making. Arguably, the source of Gascoigne’s success was her capacity to think and act differently, and to honour an object for its inherent qualities rather than assume the values attributed by general regard.

In considering the late masterwork Overland, it is important to understand the origins of her insights — and how they could be employed to transform a stack of beaten old ply into a harmonious evocation of the Australian landscape.

Gascoigne was born in Auckland, New Zealand, in 1917. She graduated from the University of Auckland in 1937 with a Bachelor of Arts (majoring in English, French, Latin, Mathematics and Greek) before training as a teacher and teaching English, Latin, French and History at Auckland Girl’s Grammar School between 1938 and 1942. When Gascoigne arrived in Australia in 1943 to marry Ben Gascoigne, a New Zealand-born astronomer working at Mount Stromlo observatory outside Canberra, she found herself somewhat isolated in what was a small foreign community, though she refused to be confined by distance and social expectations. As Kelly Gellatly noted,

. . . far from her home and support of family and friends, she found solace in nature, learning to identify the variety of grasses and stones while on walks with the children; gradually coming to appreciate the different markers of the Australian landscape. And despite the restricted domestic conventions of Stromlo’s tight community, these found objects we eventually brought inside, where they were assembled and arranged by Gascoigne for contemplation over time.1

Subsequently, Gascoigne would study ikebana from 1962 with Norman Sparnon, a master in the Sogetsu School. Sparnon espoused the belief that ‘good design’ was the foundation of beauty and the vehicle for emotional content. While Gascoigne demonstrated great aptitude for arranging, even receiving praise from the founder of the Sogetsu School himself, her interests would continue to expand with her growing engagement in the Canberra art world.2 From this point on, Gascoigne embarked on a necessarily idiosyncratic expedition through art and nature, somewhat obsessively combing the paddocks and rural dumps, factories and junkyards for discarded materials left to weather, finding beauty in that which would normally be overlooked, and in the process, bringing everyday life into new frames of reference.

With this in mind we can recognise that landscape and art materials were, in Gascoigne’s eyes, one and the same. Moreover, only through understanding nature in its most elemental, the light and shadow, hot and cold, the wind, rain and dry — and also the vocabulary left by the elements impressions on the physical — was Gascoigne able to cast such deep impressions of the majesty instilled by the Monaro–Canberra region with such humble means.

Overland

When gridded and carefully spaced to allow a rolling continuity of surface, the 25 gently warped plywood panels of Overland recall the patchwork effect of a landscape viewed from the air, the subtle undulations of countryside, order rendered through cultivation, and the mottled effects of light and shadow. The tension between order and irregularity create a rhythmic pattern; a musicality and a geometric certainty, which could extend out in any direction and, in this way, conveys both a sense of expanse and the particularities of place. The panels’ placement on the ground further emphasises the undulating horizon, which, at this scale and body relationship, offers the audience a mind’s eye view of a land that comes from time spent piecing together a place by place, hill by hill, valley by valley. Overland ventures far beyond illustration to become an iteration of nature, a landscape at peace with its emptiness and richness.

READ more On YOUR AUSTRALIAN COLLECTION OR watch our YOUTUBE playlist

Endnotes

1 Kelly Gellatly ‘Rosalie Gascoigne: Making poetry of the commonplace’, in Rosalie Gascoigne, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, 2008, p.10.

2 Gellatly, p.11–12.

Peter Mckay is Curator, Contemporary Australian Art, QAGOMA