The entry of Napoleon’s troops into Spain in early 1808 began a tragic period in the country’s history, known in Spain as the War of Independence, and in English as the Peninsular War (1808–14).

Napoleon’s overthrowing of the Spanish Bourbon monarchy and appointment of his own brother, Joseph, as King, inspired a popular revolt in the Plaza Mayor, Madrid’s main square, on 2 May 1808. This event and the execution of the revolutionary leaders the following day were immortalised by Goya in a pair of canvases painted in 1814, both of which are in the Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

The reprisals and barbaric nature of the war were also the subjects of a print series that Goya worked on privately during the war years. The Disasters of War (Los Desastres de la Guerra) 1810–14 — not published until 1863 — provides testimony of Goya’s personal observations as well as his intellectual and emotional response. These 82 etchings depict famine, rape, torture and execution. They represent not only society’s total abandonment of humanity but also a complete repudiation of the Enlightenment belief in humankind’s ability to overcome base instincts and act in a rational and civilised manner.

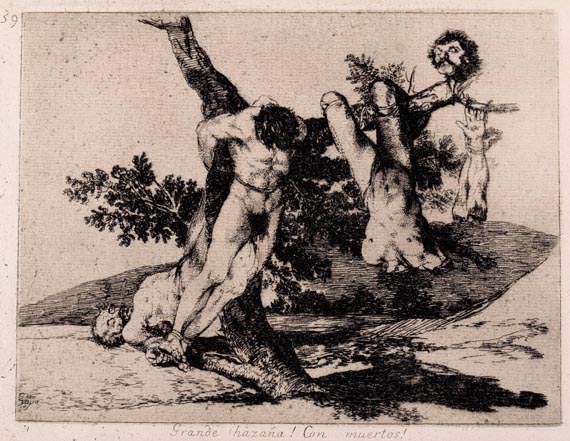

Grande hazaña! con muertos! (An heroic feat! With dead men!) is, arguably, the most recognisable image from the series — due in large part to the mass publicity it received when British artists Jake and Dinos Chapman ‘re-created’ the scene with fibreglass mannequins in Great Deeds Against the Dead 2 back in 1994. (1) The power of this print, and its evident appeal to the Chapman brothers — agents provocateurs within the contemporary art world — is that Goya extracts the essence of violence implicit in acts of vengeance. Lacking any iconography that would enable us to identify one army from another, these corpses have become generic symbols of the tragic destruction of reason. By objectifying the human body, Goya makes manifest the way these men have been stripped of their dignity — emphasised by amputated limbs and signs of castration — and the denial of any form of ceremonial honour even in death.

Goya is a giant among artists. His entire oeuvre is a sharply conceived response to the culture and epoch in which he lived, and reflects the changes he underwent personally, with his outlook on the world becoming increasingly bleak and distressed over time. It is little wonder his influence on successive generations has been vast, profound and prolonged. He is as important to contemporary art as he was to the mid nineteenth-century French and early twentieth-century moderns who revered him.

An impression of Grande hazaña! con muertos! (An heroic feat! With dead men!) from the bound first edition of Los Desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War), published in Madrid in 1863, is on view in ‘Portrait of Spain: Masterpieces from the Prado‘ until 4 November. The richly illustrated 304-page catalogue, published to accompany the exhibition from the Museo Nacional del Prado features these works.

Endnote

(1) The Chapman brothers have returned to Goya’s imagery over the course of their career. In 1993 they created a set of miniature dioramas titled Disasters of War, illustrating Goya’s series with the exactitude of model train enthusiasts, and in 1999 they ‘rectified’ (reworked) a 1937 edition of the Disasters that had been re-issued as a protest against fascist atrocities committed in the Spanish Civil War, re-titling it Insult to Injury.