Last year saw Papua New Guinea celebrate 40 years of independence from Australia, but few Australians know the history of the colonial relationship between the countries. It’s time we embraced our closest neighbour writes Sean Dorney.

In a book published earlier this year, a Lowy Institute Penguin paperback called The Embarrassed Colonialist, I argue that despite Papua New Guinea being the largest single recipient of Australian aid (more than half a billion dollars a year), Australians seem ambivalent about the country. Few know the history of our colonial rule, and our long ties to PNG are quickly being forgotten.

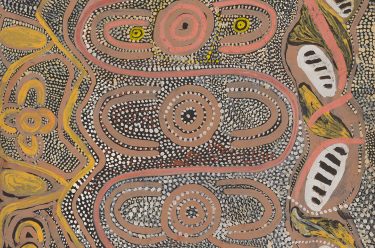

When writing The Embarrassed Colonialist, I visited the Australian Museum in Sydney to have a look at its ‘Pacific Spirit’ exhibition. Among the displays was a limited number of what the museum described as ‘rare and priceless’ artefacts, including 23 elaborate and sacred Malangan masks from Papua New Guinea dating from the 1800s. According to the museum’s curators, some of these objects had real impact when the world became aware of them; they even influenced the twentieth-century modernist movement and artists such as Matisse and Picasso. The curators told me that there are more than 31 000 other ethnographic items from PNG in their collection. Most of these have hardly ever been seen, except by those who keep them stored in the vaults. Other museums around Australia also have PNG collections, some of which are occasionally put on display. But, a bit like the relationship between the two countries, much of this traditional artwork has been locked away in the basement, out of sight.

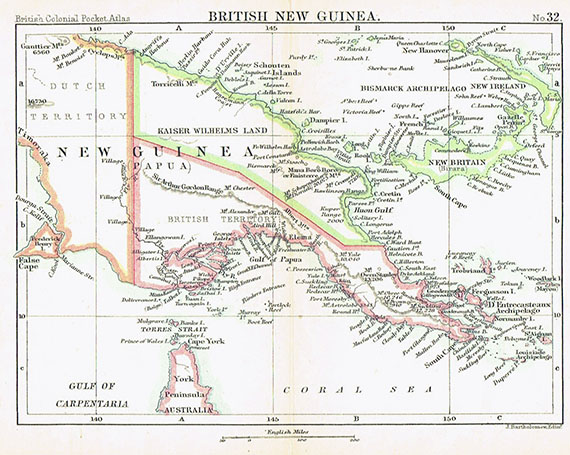

Queensland was still a colony of the British Empire when it tried to claim the eastern half of the island of New Guinea in the early 1880s. The Queensland premier at the time, Thomas McIlwraith, sent Henry Chester north from Thursday Island with a party in a Queensland government vessel to annex what is now Papua New Guinea. The British government repudiated the annexation: according to the late Professor Hank Nelson from the Australian National University, it was because the British ‘were not willing to allow colonies to gather colonies’. He said that the British government was also acting on advice that the Empire ‘already had black subjects enough’ and that Queensland at the time regarded its own Aborigines as ‘vermin to be cleared off the face of the earth’.

Nevertheless, in 1884, with the Australian colonies badgering the British about German intentions, Britain began negotiating with Germany about dividing eastern New Guinea in two. (Years before this, the Dutch had already taken the western half of the main island of New Guinea to add to their empire in the East Indies — present-day Indonesia.) In November 1884, within days of each other, the Germans raised their flag in the north and the British the Union Jack in the south. The Germans called their colony Kaiser Wihelmsland and chartered private business firm die Neuguinea-Kompagnie (the New Guinea company) to run it. Australia took control of British New Guinea soon after Federation in 1901 and its name was changed to Papua under the Papua Act of 1905. When World War One began, Australia’s first military foray was to seize German New Guinea. The first Australians killed while wearing Australian military uniforms, Captain Brian Pockley and Able Seaman William Williams, died in that action.

After the war, at the Versailles peace conference, Australian prime minister Billy Hughes demanded that Australia be given permanent control of German New Guinea. Despite opposition from the prime minister of Great Britain and the president of the United States, he won a League of Nations mandate that led to the establishment of separate Australian administrations in New Guinea and Papua. They were run quite differently. The Lieutenant Governor of Papua, Sir Hubert Murray, argued that he should be given responsibility for New Guinea, too, but the Australian government decided that the land — alienated from the local people by the Germans — would provide an excellent soldier settlement scheme. The plantations were expropriated, the Germans turned out of their homes, and Australian ex-servicemen encouraged to take up a new life there. Former prime minister John Howard’s father and grandfather were two of the ex-servicemen to be granted German plantations but they never went to take them up.

DELVE DEEPER INTO THE ART OF PAPUA NEW GUINEA

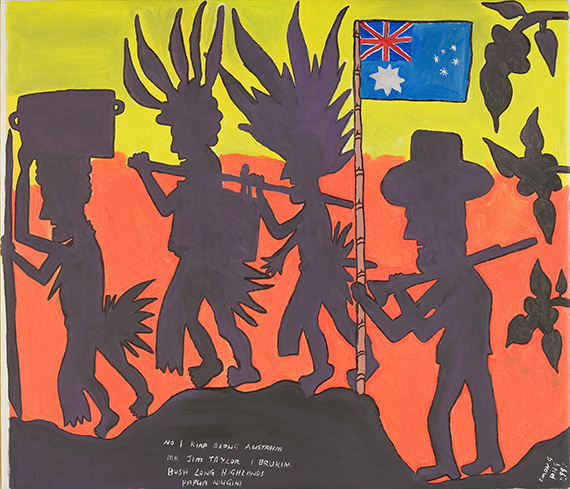

‘No.1 Neighbour: Art in Papua New Guinea 1966–2016’ is at the Queensland Art Gallery until 29 January 2017

The two administrations came to a sudden end in World War Two, when the Japanese swept aside any Australian resistance in New Guinea but were then repulsed in a series of battles at Milne Bay, on the Kokoda Track and at Buna, Gona, and a dozen or more other battlefields. As many as half a million Australian military personnel served in Papua New Guinea during World War Two. My father, Kiernan ‘Skipper’ Dorney, was one of them. A doctor, he became Australia’s most highly decorated medical officer in the whole war, being awarded the DSO (Distinguished Service Order). He was a Major in charge of a section of the 2/3 Australian Field Ambulance which, together with the 2/32 Infantry Battalion, was cut off by the Japanese after capturing a strategically important hill at Pabu, inland from Finschhafen on PNG’s northern coastline.

His citation reads:

Major Dorney, without sleep for five days, tended the wounded of his section, which was continually subjected to mortar fire. Many times he personally helped under fire to bring in the wounded.

Following the war, a single administration was created to run what became the United Nations Trust Territory of New Guinea and the Australian colony of Papua. In the 1950s and early 1960s, there was very little expectation that the Territory of Papua and New Guinea would get its independence before the turn of the century.

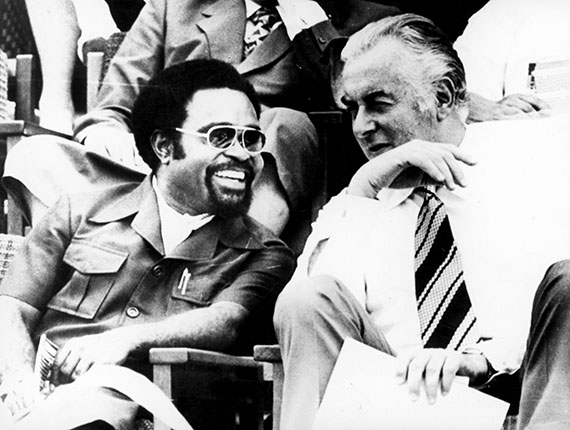

In 1963, just ten years before PNG moved to self-government, Professor Nelson wrote that ‘no Papua New Guineans occupied senior positions in the public service. No Papua New Guinean had graduated from university, and only 25 were at the top of secondary school’. So independence came with a bit of a rush. Gough Whitlam made early independence for PNG an Australian election issue in 1969. Michael Somare, whose Pangu Pati had campaigned Sean Dorney and his wife, Pauline / Image courtesy: Sean Dorney for early independence, put together a coalition government of small political parties and independents in the Territory’s elections of 1972 (only the third Territory-wide elections ever held in PNG). A few months later, when Whitlam won in December 1972, he ensured that PNG got self-government in 1973 and full independence in 1975.

I say that it is time we shed our embarrassment about our colonial past and embrace our relationship with our nearest neighbour, and that is why I am so pleased to have been asked to contribute to Artlines in support of the exhibition ‘No.1 Neighbour: Art in Papua New Guinea 1966–2016’: because I firmly believe PNG should be ‘Number One’.

I spent 20 years living in Papua New Guinea and was constantly impressed by the quality of the art — not just the wonderful ethnographic objects but also the works made over the past 50 years. And PNG’s contemporary artists continue to produce stunning works. I trust you will enjoy this exhibition as much as I anticipate that I will.

Sean Dorney, a Lowy Institute Fellow, was a foreign correspondent for more than 30 years including 17 heading up the ABC’s Port Moresby bureau. He lives in Brisbane with his wife, Pauline, a former PNG radio broadcaster from Manus Island.

This is an extract from the Gallery’s Artlines magazine available from the Gallery Store. Keep up to date with the Gallery’s seasonal publication delivered each quarter to QAGOMA Members.