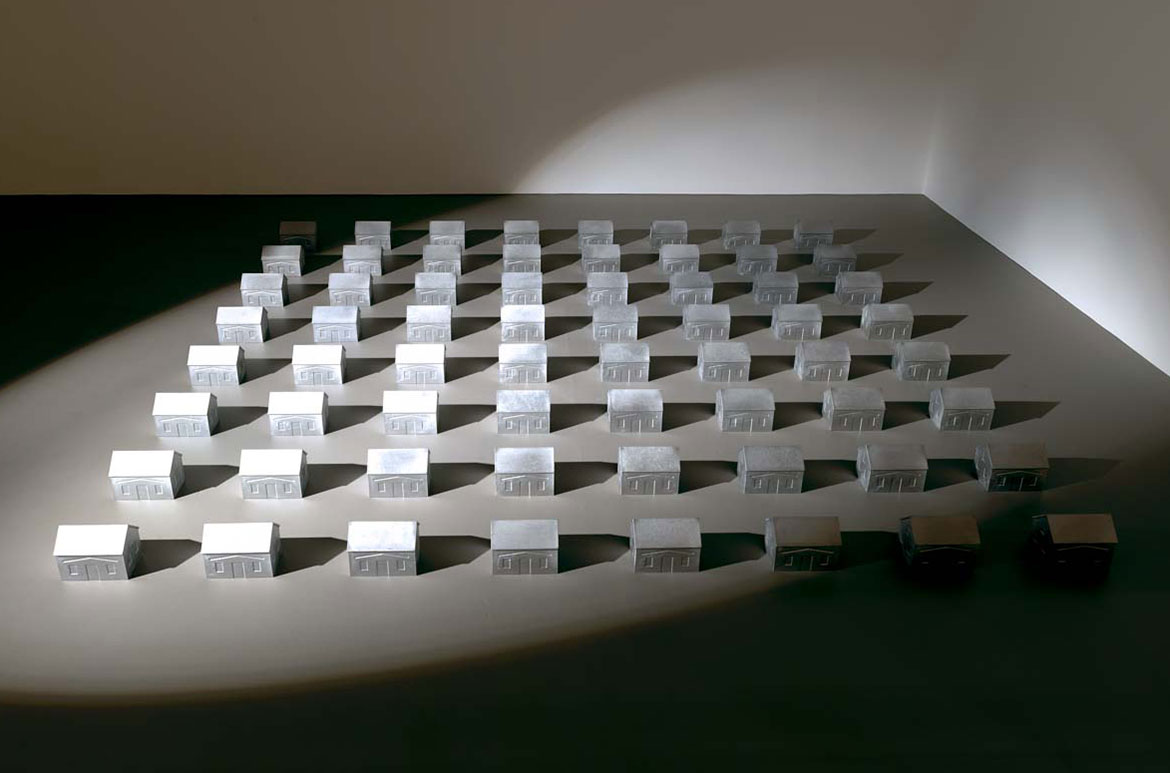

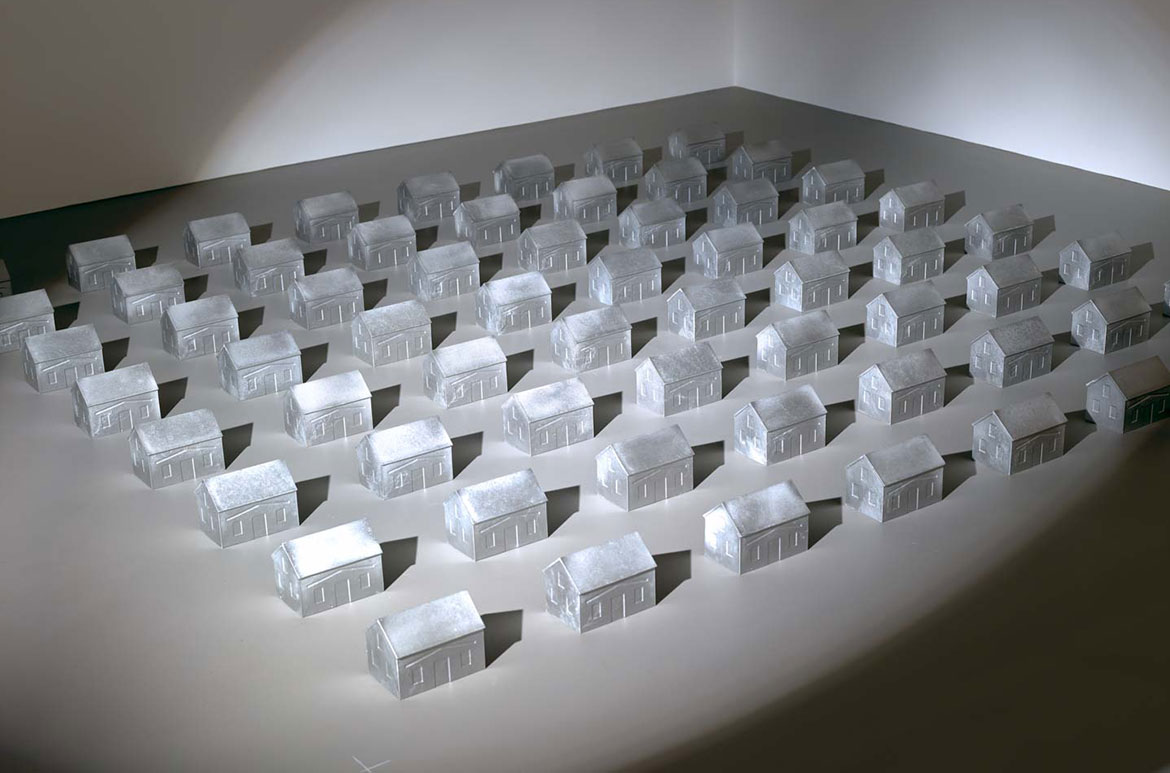

DAY IN DAY OUT (second version) 1991 by Aleks Danko has recently been installed in the reimagining of the Australian collection at the Queensland Art Gallery. This important and enduringly captivating work is for the first time, given a place in a ‘permanent hang’ of the Australian collection in a context which is both diverse and relevant. It has been included previously in various iterations and thematic displays, but its inclusion in the new perspective for the collection is both timely and as topical as ever as Australia confronts increasingly shrill debates about home affordability, border security and social division. The power of Danko’s work is in its understated, unadorned directness in addressing issues that we all share. This blog is an extract from David Burnett’s essay published in Lynne Seear and Julie Ewington (eds). Brought to Light: Australian Art 1850-1965, Queensland Art Gallery, 1998.

It was, in fact, the installation’s title that had immediate resonance for me. My mother (and I suspect many others) had used this very phrase often when I was child. I recalled that it was after she took on jobs, first as a cleaner in a nearby motel, and then later as a cook at a nursing home, that this chant-like phrase entered our domestic realm. I remember the pattern of life changing with both parents working. There were adjustments to new routines and schedules for myself, my brother and my sister. Evening meals moved from the kitchen table to the lounge room, in front of the television to catch Flipper or Bellbird before the news at seven. ‘Day in, day out’ was a phrase I came to associate with my mother’s tiredness and seemingly endless chores — cooking, lunch-making, washing, cleaning and ironing — which she performed at times she never seemed to before. I grew to resent this routine as it came to dominate our lives. For me, it was through this portal of memory that Danko’s installation of little houses with their long shadows took on particular significance, and prompted a kind of gentle, backyard melancholy.

DAY IN DAY OUT (second version) incorporates a revolving theatrical light – an electronic sun which introduces and implies the element of time in the work. It has an effect similar to time-lapse photography, where the movement of clouds, light and atmosphere is compressed into minutes and seconds. The diurnal cycle defined in this work is measured by a clock that spins rather than ticks. It is mechanical time, factory time, ‘no-time-to-dream’ time — a time that is alienated from experience, indifferent, relentless — day in, day out.

Aleks Danko’s career spans a defining period of Australia’s recent history.1 His childhood was spent in suburban Edwardstown in Adelaide. In the early 1970s, he studied sculpture at the South Australian School of Art. Feminism and gender politics, the anti-uranium and conservation movements; the dismissal of the Whitlam Labor government; the volatile passage of the Hawke and Keating administrations; and, more recently, John Howard’s ‘relaxed and comfortable’ euphemism of ambient anxiety and fear, have provided the background noise for Danko’s critical aesthetic strategies. From an era of reformist hope and optimism to one of nervous, timid quiescence, his art has engaged with debates through a mordant wit and irony, simultaneously disarming and activating issues.

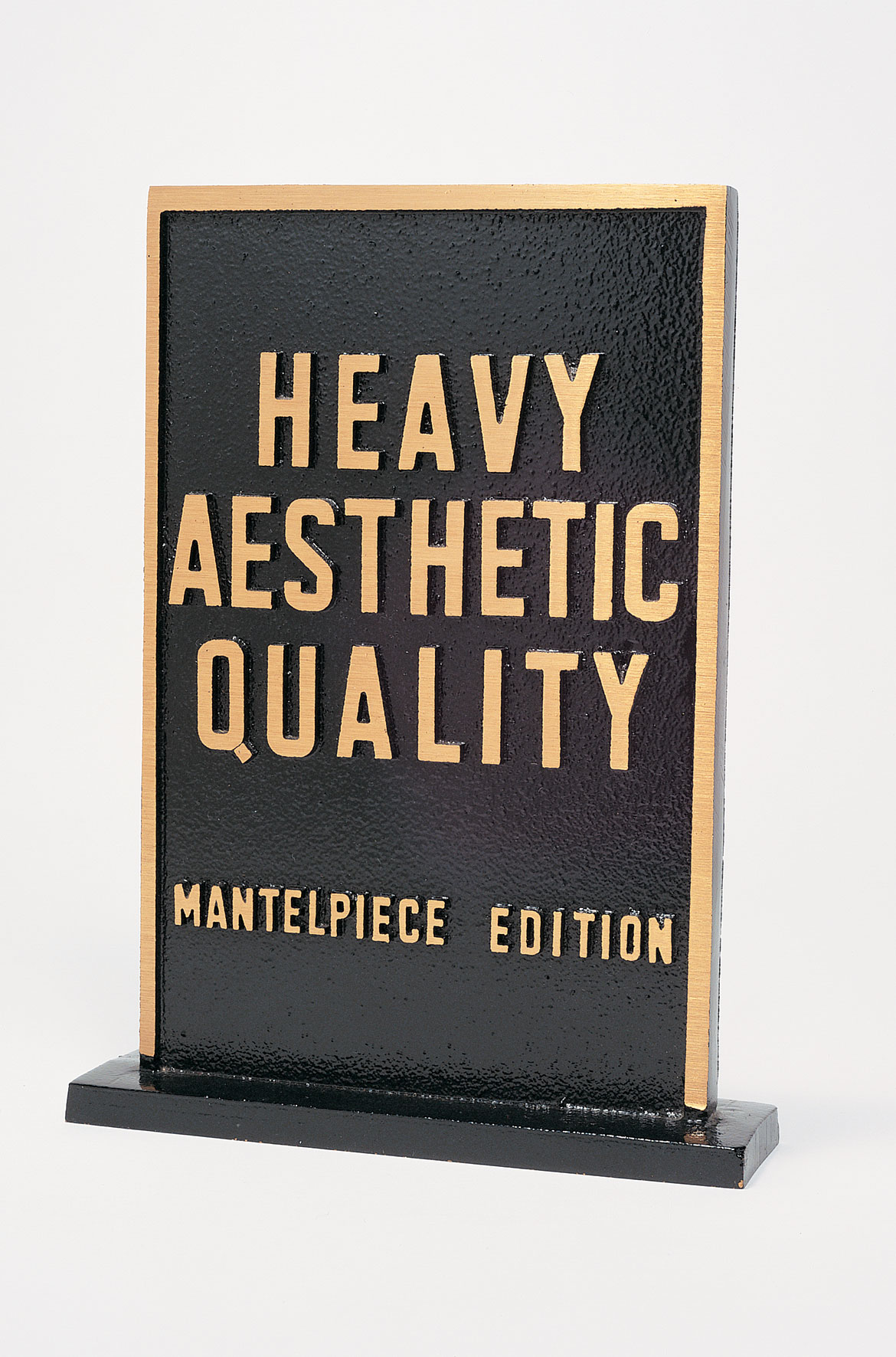

From the early 1970s, Danko’s work embraced a neo-dada, conceptual dimension, but with its roots in the local. His work engaged with Conceptual and Post-object art to the extent that it critiqued the formalist, institutional aesthetic of the previous generation. It did not follow, for example, the more austere forms of Conceptualism, where texts and photographic documentation became the residual ghosts of ideas. The arrangement of DAY IN DAY OUT (second version) may reference the formalist grid of Modernism, however it does not assume the mute objectivity which characterised the minimalist aesthetic of artists such as Donald Judd or Carl Andre. Danko’s language of irony, Duchampian play and metaphor keeps the work circulating in an orbit of immanent possibilities and potential meanings. As a strategy, irony is open-ended — it has no end-game. It plays itself out by creating small ruptures in the fabric of language. It irritates, but never nullifies meaning, by having an alternative always at hand. It forces us to remain vigilant to the fact that reality is essentially provisional, equivocal and contestable.

DAY IN DAY OUT (second version) confounds notions of scale and time, the ordinary and the monumental. Its formality is deftly undermined by its installation at floor level — no enhancement, pedestal or plinth — just anonymous little houses resting on the indifferent floor and, by inference, the earth. While the work is composed of small, identical houses, it is less about ‘home’ than it is about time and a sense of alienation. The spaces between these houses are pregnant with the disconnectedness that characterises the Australian suburb. The irony of the work is amplified when we know that the multiple dwellings are cast from a house-shaped cake-tin mould. This dinky piece of domestic kitsch becomes the template for several of Danko’s important works and projects — works that take the idea of home into a wider political and philosophical arena. Its childlike facade is both cute and menacing. The suburban house on the quarter-acre block has traditionally been the primary foil against alienation and ‘not-at-home-ness’ for non-Indigenous Australians. It is here that we seek refuge and security.

To drive into, or out of, any major city in Australia by freeway is to traverse the zones of housing that have come to define everyday life in Australia. The older suburbs of humble red brick bungalows and postwar weatherboard cottages contrast sharply with the new wave of eave-less, double storey ‘McMansions’ squatting on freshly cleared plots ‘landscaped’ with pine bark and palms. Our coastal hugging population’s love affair with home ownership has been a social, political and economic indicator for decades. Australia’s boom and bust cycle is driven as much by the movement and relocation of transient populations as it is by the buying and selling of real estate. In urban Australia in particular, the notion of home as a dwelling, an asset, as ‘bricks and mortar’, tends to supplant the idea of home as a place of belonging. ‘Being at home’ for white Australia is first and foremost about a sense of security underpinned by ownership, before it is about a sense of shared spirit of belonging. Highly geared mortgages keep the dream in place, but out of reach, for longer, while we work ever-increasing hours to close the gap between aspiration and acquisition.

For some artists and writers, however, suburbia has been a site for nostalgia, fondly remembered childhood events, and the source of Dame Edna’s satire. Tim Winton’s vignettes of seaside country towns or David Malouf’s evocations of Brisbane in the 1950s are sometimes haunting in their imaginative descriptions and ability to extract mystery from the achingly familiar. This represents the duality and the ambivalence that filters the experience of Australian suburbia. Australian films and television soap dramas, such as Neighbours ,have created a particular image of the suburbs that can be seen as both reflection and artifice. The summer heat and ennui of Porpoise Spit in Muriel’s Wedding (1994) or the folksy heroism and shed humour of The Castle (1997) are further examples of how we reflect on our status as largely suburban dwellers.

The meaning of suburbia is constantly being negotiated. It swings from the celebratory image of backyard barbecues and pools to outlying badlands of unemployment, disadvantage and violence.

Danko has attributed a statement to his father which perfectly encapsulates the ongoing ambiguity of prevailing attitudes to suburbia: ‘As you know, we are pensioners, day in day out, twenty-four hours closer to death’. The artist cites the phrase as an example of Russian black humour — a dark and self-deprecating humour — it can raise a smile and a shudder in the same instant. It is also one that finds affiliation in the more sardonic and mocking strains of Australian humour. It is a statement of both resignation and affirmation. It can be taken as a colloquial embrace of Henry David Thoreau’s statement, ‘The mass of men live lives of quiet desperation’, and equally as a matter-of-fact description of life in which one is still free to love one’s wife, pat the dog and see the sun come up tomorrow.

For Aleks Danko’s father, the establishment of a ‘home’ in Adelaide in the 1950s most probably represented the pinnacle of hard work and security, as it was for many immigrants at the time. Emigration, whether by choice or necessity, was a central phenomenon of the twentieth century. Fundamental to it was the idea of loss — the loss of home as the centre of one’s world, where one is connected by blood to others, and to history by experience. The displacement of the migrant is never fully resolved. The experience of arriving and living among strangers creates conditions in which fragments, memories and longings are constantly being reconfigured in an effort to create a semblance of that which is lost.

DAY IN DAY OUT (second version) is a work whose meaning oscillates and like much of Danko’s work, is constantly slipping between language and image, past and present, metaphor and real life. Irony, paradox and humour are his companions and combatants in a society where history is abbreviated into ‘mini-series’ and human relations are replaced with the abberation of ‘reality television’– where short-term memory and long-term credit delivers us from responsibility – a society insensible to contradiction — where opinion polls and statistics are the pretence for democratic choice. Where fear is the new currency.

This work retains its power to provoke, it remains a potent indice of the ambiguous ‘values’ and politics of a strangely retro climate of social division, distrust and conservatism, masquerading as a new prosperity. On a good day, we might see rows of cosy homes, secure in their routine constancy, untroubled by maverick otherness, rising interest rates or foreign threats. On a bad day . . . why can I not help thinking that it looks like a mordant monument to a phenomenon that once represented a new life, a tiled roof utopia for many who were driven from their countries of birth by war, famine and internecine strife? The modest home that Danko’s parents established in the 1950s in the suburbs of Adelaide — optimistic, proud and comfortable — is difficult to identify in their son’s tableau of terminal emptiness.

There is no argument that a majority of Australians enjoy a standard of living that rates among the highest in the world. For that majority, this life of the workplace, the home, the mortgage, sunny leisure and lifestyle channels, celebrity gossip and next weekend’s barbecue or backyard makeover, is enough to keep us in an attenuated state of distraction.

What time is it in suburbia?

David Burnett is former Curator, International Art, QAGOMA

Endnote

1 Aleks Danko was born in 1950 to Ukranian parents who fled Stalin’s paranoid and oppressive regime of collectivisation. They married in Germany and joined the first of successive waves of dispossessed refugees, immigrating to Australia and arriving in Adelaide in 1949.

Extract from Lynne Seear and Julie Ewington (eds). Brought to Light: Australian Art 1850-1965, Queensland Art Gallery, 1998

DELVE DEEPER INTO your australian ART collection

Feature image: Aleks Danko’s DAY IN DAY OUT (second version) 1991

I’d like to sign up to this great blog – been a QAGOMA member for three years, yet never seen this before…and still can’t see the blog sign up (already get enews). The Aleks Danko piece was great.

Hi. Thank you for making contact and your positive feedback, there is a subscription sign up link at the bottom of the blog pages > https://blog.qagoma.qld.gov.au/