At a time when most Australian galleries were temple-like buildings that upheld the exclusivity of art appreciation, architect Robin Gibson’s Queensland Art Gallery was truly extraordinary: through the language of Modernism, Gibson’s intention was to democratise art and bring it to the people.

Louise Martin-Chew spoke with QAGOMA Director Chris Saines CNZM on his plans for the building which opened 36 years ago in June 1982.

An architectural evolution

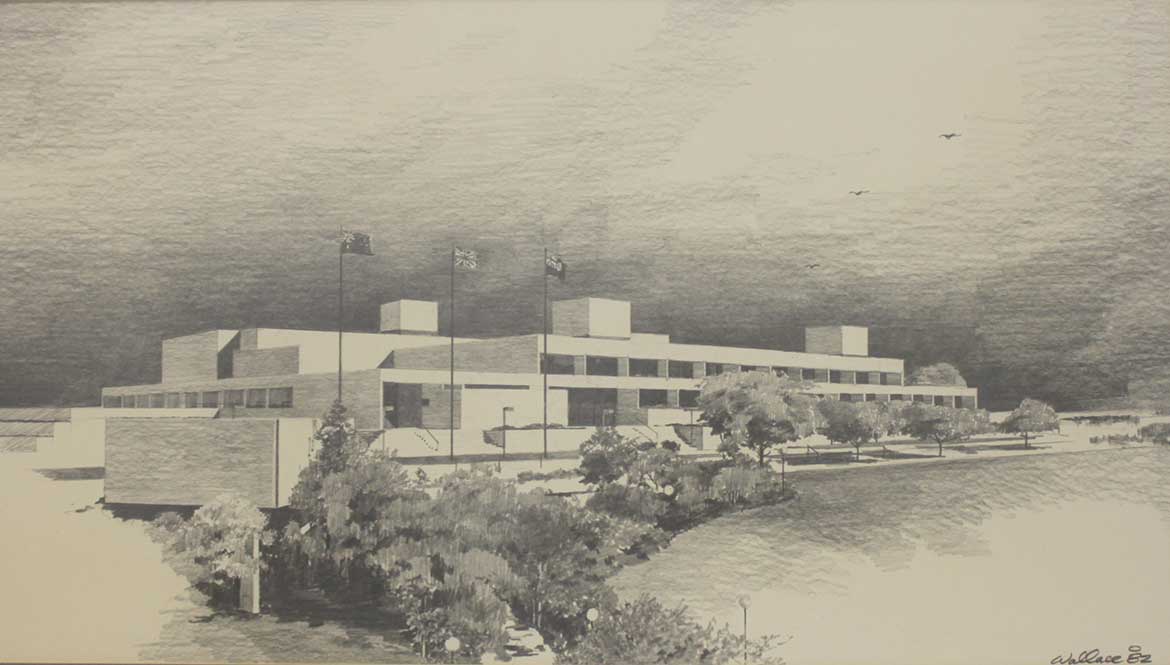

The Queensland Art Gallery is arguably the most successful building designed by architect Robin Gibson AO (1930–2014), and was widely admired when it opened in 1982 — Gibson received the prestigious Sir Zelman Cowen Award for Public Architecture that same year. It was visionary for its time, and Gallery Director Chris Saines remains impressed by Gibson’s foresight, his ability to design for functionality as well as the quality of his aesthetic vision. ‘The beauty and legibility of this building’, he says, ‘is a product of Gibson’s relentless application of an organising principle. Every space is generated off a 2.5-metre-square grid — an open and modern response to a classical design tradition’.

While some were critical of the brutalist, monolithic appearance of the Gallery’s exterior, the internal spaces are both functional and beautifully managed. Saines notes that:

It is a satisfying building in its harmony between the scale of the body and the spaces. While there are the grand elevated spaces of the Watermall, others are relative to human scale. The mezzanine around the edge of the Watermall offers breaks and half breaks between the floors. This is also a building with notable natural light. In Gibson’s era, art was primarily about painting. Within a painting’s construction and viewing is a parallel engagement with the business of light.

Saines worked at the Queensland Art Gallery from 1984 until 1995, and on his return, when he took up the QAGOMA directorship in 2013, he noted the many changes to the building that happened in the intervening years. The idea of restoration began when Saines reopened a sealed window wall in the Queensland Art Gallery’s Philip Bacon Galleries (7, 8 and 9) — a decision celebrated by staff who were grateful for the restoration of daylight in the space, which houses works from the international collection, and for the vista to the fountain outside. Heritage listing of the entire Gibson-designed Cultural Centre in 2015 added an additional imperative to this work, but for Saines, the incentive to restore the Queensland Art Gallery lies in enhancing enjoyment of its collections and the unique nature of the place:

As a visitor to this gallery, you were originally offered connections to the city, then you moved into the gallery and the Watermall, which is flooded with light. Gibson’s building speaks to the Brisbane River, with the Watermall in precise parallel with the river outside. It is a spacious and airy volume, with daylight streaming in both ends. However, former public spaces, including the original Gallery society rooms and library, have long been closed off as back-of-house accommodation needs increased over time. They were spaces the public could really enjoy. This access to the river, at the same time as the art collection, was Gibson’s democratic civic gesture.

However, the reinstatement of Robin Gibson’s architectural integrity is not about nostalgia, and the heritage listing itself does not suggest that the building should be frozen in time. New display cabinets echo the proportions and style of the Gallery’s ceiling coffers, as do the seats being progressively updated throughout. Gibson may not have envisaged these newly designed items, but they refer to his proportions and motifs in a contemporary iteration.

Art is not known to cause major changes in mainstream society, but it is quietly revolutionary — from Picasso’s Guernica 1937 and Charles Dickens’s novels, to the current use of Australian Indigenous paintings in native title claims to provide evidence of continuous occupation. The recently unveiled display of Australian art in QAG’s Josephine Ulrick and Win Schubert Galleries (10, 11, 12 and 13) combines Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art with other Australian works produced in the last 150 years, and this opens visual conversations, challenges existing conventions, and choreographs an interchange of styles and cultures. It is an important example of cultural diplomacy, and revolutionary in a way that may not be fully appreciated for years. Saines describes this change simply as ‘a gesture of restoration’, adding that:

We needed to remix the collection in a way that took account of 99 per cent of Australian cultural history. We know now that Indigenous culture spans some 60 000 years. The time since colonisation is less than one per cent of that.

Saines’s 17 years in New Zealand, a country that manages its recognition of Indigenous cultures differently to Australia, is visible in this change of focus:

The reimagining of the Australian Collection captures major historical moments from first contact to colonisation, and exploration to immigration. Bringing the Indigenous and contemporary Australian collections together with the Gallery’s historical holdings, the display emphasises stories about Queensland and Brisbane from the region’s own perspective.

The back galleries show the way in which Australia has multiple art histories, not just a post-contact history. We are elevating that story. It doesn’t feel radical; it is evolutionary, not revolutionary.

What may be less obvious is that this change of focus has taken place in concert with the continuing architectural refurbishment. While the restoration of sight lines in the Australian galleries echoes the architect’s original vision, the reopening of windows and portals offers the luxury of light and air — not just to the physical space, but also to the works on display and the histories they represent.

The next priorities, with some slated to begin in 2018–19, include reopening closed circulation paths and sight lines where public access to river views is currently limited, restoring access to previously public rooms on the mezzanine level, and reinstating the walkway above the Watermall, which originally led to a gallery space devoted to works on paper. Removing partitions on the Watermall level will also restore the openness of the decorative arts gallery.

The revolutionary nature of Robin Gibson’s building, commissioned by Queensland’s conservative Bjelke-Petersen government, is all the more extraordinary when it is considered that most Australian galleries at the time were temple-like buildings (like the Art Gallery of New South Wales or National Gallery of Victoria), and presented art as an elitist enclave. Gibson used modernist language with the intention of democratising art and bringing it to a civic level. As the architect attested in a statement in 1982:

It is not only a place for the collection and exhibition of our artworks, it is a place where the walls and barriers of the Gallery are broken down, where there is a constant source of interchange between the art world and the public.1

Robin Gibson AO looked to modernist international precedents to design the Cultural Centre that has since become integral to Brisbane’s architectural iconography. The coming changes at the Queensland Art Gallery will honour his visionary design, and recognise the exemplary building that is his legacy.

Endnote

1 See ‘Our Story’, www.qagoma.qld.gov.au/about/our-story/architecture, accessed November 2017.

Featured image: The Melbourne Street entrance to the Queensland Art Gallery, South Bank / Photograph: Mark Sherwood © QAGOMA

#QAGOMA

I was 16 in 1982 and became a regular visitor to the new Queensland Art Gallery over the next couple of years. It was a second and better home, providing a peaceful, contemplative and inspiring haven of space and light and calm water for a troubled teen. I feel a great love and nostalgia for this place, remembering a small girl dancing lyrically, ecstatically, one afternoon to a chamber concert in one of gallery spaces.

Thank you for this space. Thanks to all the creative gods for the arts.

How can we raise the understanding and respect and reverence for its place in our culture, as colonial Australians, as contemporary Australians?