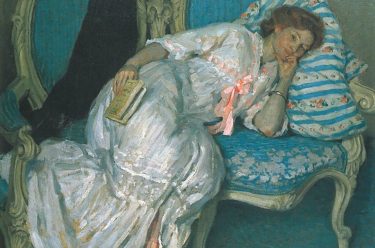

Arthur Boyd’s Sleeping bride 1957-58 is from the celebrated allegorical series of paintings ‘Love, Marriage and Death of a Half-Caste’ — often known as the ‘Brides’ — Sleeping bride is one of Boyd’s defining contributions to Australian art. The Victorian-born artist is, together with his contemporaries Sidney Nolan, Albert Tucker and Joy Hester, among the towering figures of the Australian Modernist movement.

Alongside Nolan’s ‘Kelly’ paintings and Tucker’s ‘Images of Modern Evil’, both from the ‘40s, Boyd’s ‘Brides’ persist to this day as one of Australia’s most intriguing and immediately iconic series.

Born into a family of artists, potters and sculptors in 1920, Boyd — who died in 1999 — is arguably the most pictorially and creatively inventive of twentieth century Australian painters. Early in his career he was drawn to a mutable and occasionally explosive form of expressionist figuration — most were Melbourne-centric; a playing out of the psychic end-dramas of a world consumed by war. At the outset of a career characterised by unending stylistic oscillation, he then found a kind of rhythmic and pictorial reset in the bucolic hills around his Berwick home. By then, Boyd had located what would be a lasting affinity with European art history and with its Christian symbolism and mythology.

Indeed, much of the work made approaching the late 50s, the moment of the ‘Brides’ series, was at the outset nourished by the forcefully psychological writing of Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Franz Kafka, and then seemed to draw directly off the painterly grid of Oskar Kokoschka and Pablo Picasso. What followed was a foray into vast and teeming biblical subjects, which brought to the local landscape the unlikely influence of Bosch, the occasional nod to Brueghel, and the deeply human drama of Masaccio.

Throughout the ‘50s, Boyd returned to more naturalistic, sometimes idyllic paintings of the archetypal Australian bush; Gippsland scrub parched for water but drenched in light; straw-coloured paddocks festooned with hayricks and farm equipment, the sky ringing with a raucous chorus of crows.

This is what preceded a decisive trip that Boyd was to take to central Australia in 1953. He visited the artist Rex Battarbee, who had such a formative influence on Albert Namatjira, travelled on the Ghan from Port Augusta to Alice Springs, then finally out to the former mining settlement of Arltunga, where he camped and drew incessantly.

Here, for the first time, Boyd encountered Indigenous Australians in shanty towns along dry riverbeds, living under corrugated iron in squalor and abject isolation from the nearby white population.

This had a stunning and lasting effect. According to Ursula Hoff, the first to write comprehensively on his work, ‘the blacks he saw were neither ‘noble’ nor ‘comic’ but tragically suspended between two worlds’.

Hoff said the bride motif ‘brought back a memory of an open truck at Alice Springs which carried a number of Aboriginal women to church, their white bridal finery contrasting with a method of transport more fitting for cattle. Boyd’s leading theme, she says, is frustration.

The watershed series which arose from this encounter, and to which Sleeping bride belongs, didn’t fully crystalize in Boyd’s imagination until a few years later, between 1957–58, when he painted 16 ‘Bride’ series pictures, which were first shown under the title ‘Allegorical Paintings’ at Australian Galleries in Melbourne, then in Adelaide and Sydney. The series eventually consumed him and he went on to create more than 40 major paintings, this one included, between these years and up to 1960, the last executed in London.

Although there is no coherent narrative enjoining the series, unlike Nolan’s ‘Kelly’ — different paintings register very different levels of cultural agency, tension and even violence – giving the ‘Brides’ a ballad-like cadence. The crux of the story is the doomed affair between a man of mixed-race and his so-called ‘Half-Caste’ bride, who in some paintings also appears in reflection or as an ethereal doppelganger. This marked a turning point for Boyd and for the representation of Indigenous Australians by artists of European descent.

The ‘Brides’ were painted in the later years of the federal government’s assimilation policy and the stolen generations, which saw children of mixed-race removed from their homes. Indigenous scholar Marcia Langton, has observed that Boyd’s ‘artistic practice was an expression of his encounter with the Aboriginal world in the early 1950s, and its assault on his psyche’. Indeed, the history of that representation is embedded in these elusively episodic, psychological, and sometimes brutal paintings.

In the rhythm of the series, the Sleeping bride marks a comparatively tender interval, an exhalation of breath, a rare vision of the bride alone. The dark, blue-tinged landscape — likely set by Boyd in the Great Dividing Range — puts us in an ambiguous realm of half-light. Perhaps it’s an early morning light not yet fully awakened, like the bride, from a suspended dream state. It’s this sense of the bride ‘not quiet’ floating over the ground that bears her weight that evokes the paintings of Marc Chagall, but there is none of Chagall’s fantastic levitation and none of his ecstatic states here. This is, indisputably, 1950s Australia.

The pictorial anatomy of the Sleeping bride does, however, summon up several of the most insistent European art influences on Boyd. They are seen in the head of the bride, recalling Picasso’s Boisgeloup figures, and any number of his versions of a sleeping women; and they are even found in the scumbled treatment of the translucent white dress, which might have its painterly descent in Boyd’s admiration for Tintoretto’s and Rembrandt’s use of tempera and oils.

There is also the symbolic anatomy of this painting, a very particular ‘Boydian’ iconography, which includes a luminous green scarab beetle, an Egyptian symbol which refers to the rebirth of the sun each day; a ‘ram-ox’, a hybrid symbol — part ox, part ram — entirely invented by the artist to suggest strength and fertility; and of course the crow, the harbinger of doom or death. Finally, there is the posy of flowers. Do they denote an imminent or recent wedding, or foretell a funeral — and might not the blue ones be anemones, ancient Christian symbols of sorrow and death?

Taken together, Boyd is registering a remarkably complex state of mind here, one in which his bride finds herself utterly abandoned to sleep — a state that might equally signify her being seized variously with fear, sadness, lust, or the hope of renewal.

The ‘Bride’ series, according to Robert Hughes, and more recently Kendrah Morgan, was also informed by his then tumultuous personal life. Hughes called the Brides ‘the search of a man for love’, and Morgan recounts the story of Boyd’s lover at the time, the artist Jean Langley, whose diaries recount her giving him a bunch of flowers to take to his wife Yvonne, then languishing in hospital with a nervous breakdown.

Whether the ‘Brides’ series was conceived or evolved as an allegory of the alienated outsider, as a pointed social and political critique, or whether it also embodies the after-effects of the immense turmoil in Boyd’s personal life at the time, it remains a complex, contested and rightly celebrated body of work in Australian art history. It is, likely, all of these things.

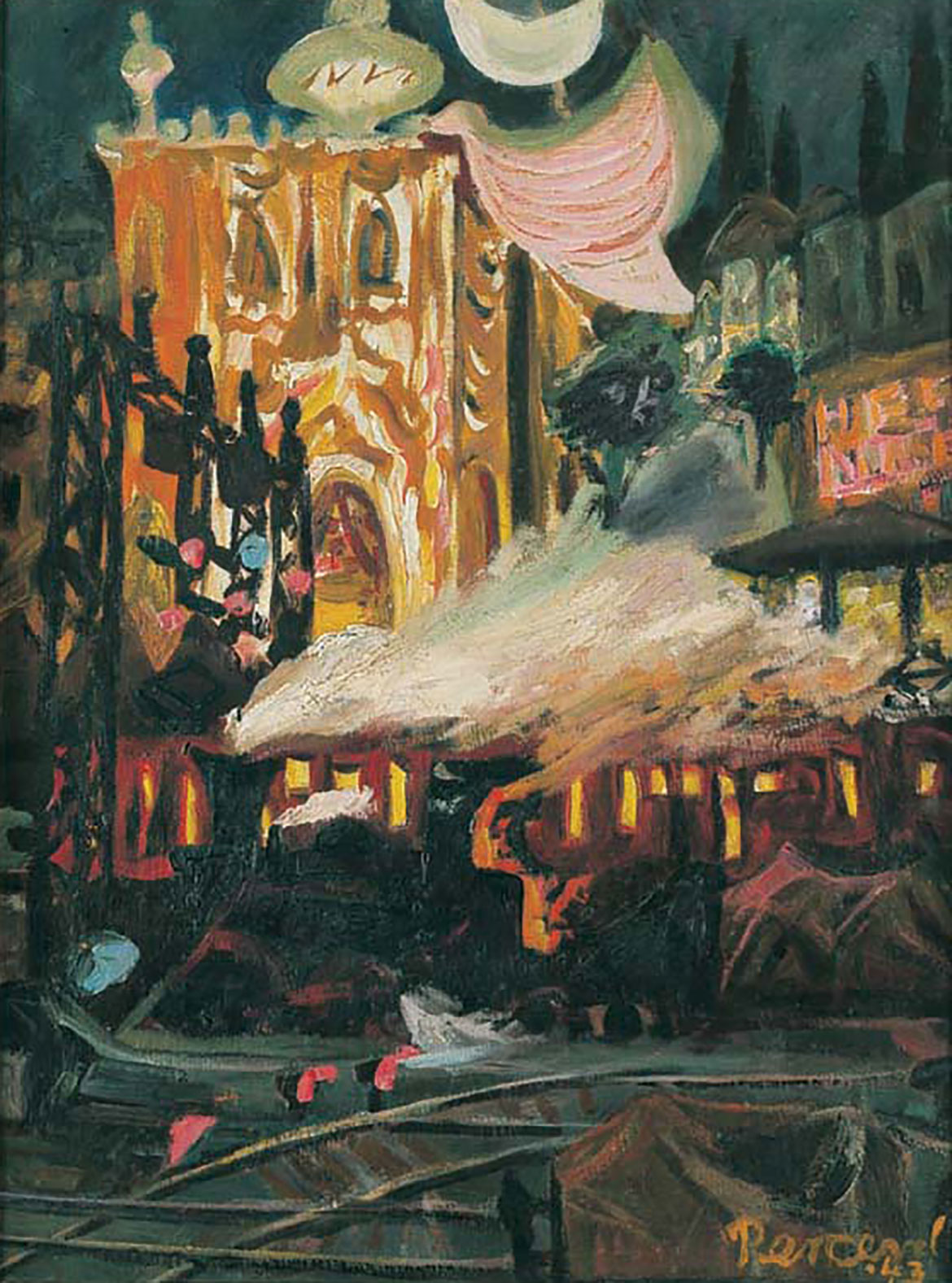

It seems apt then, in this context, that Sleeping bride was at first a gift to Boyd’s sister Mary and to his brother-in-law John Perceval, whose own work hangs nearby.

For the Gallery’s Collection, Sleeping bride is an exemplary painting from a highly significant moment in Australian art history; one which will dramatically expand the dialogue we can create between our holdings of Sidney Nolan, Russell Drysdale, Albert Tucker and William Dobell, together with Boyd himself.

This major, mid-century modernist painting from Arthur Boyd’s most prominent series will exert a uniquely unmatched impact on our Collection. As influential critic and curator Bryan Robertson, who first showed the ‘Brides’ at Zwemmer Gallery in London, said: ‘These paintings do not require any explanation. They speak with their own voice of something which the artist feels very passionately. They are tough pictures, filled with an almost lurid… intensity of movement, stillness and colour.’

And it is just that: a deeply felt, deeply human painting.

Chris Saines CNZM is Director of the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA)

Know Brisbane through the QAGOMA Collection / Delve into our Queensland Stories / Read more about Australian Art / Subscribe to QAGOMA YouTube to go behind-the-scenes

Sleeping bride, was originally gifted by the artist to his sister Mary and brother-in-law John Perceval. It was then held in private collections in London, Melbourne and Brisbane prior to being gifted to the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art.

One of the most significant individual works of Australian art ever gifted to the Collection, Sleeping bride comes from Paul Taylor in memory of his parents, Eric and Marion Taylor. The Taylors were passionately committed to family, education, community and service. For Paul and his wife Sue, the gift made in their memory makes a compelling contribution to the QAGOMA Collection.

This is an edited version of an address given at the 2016 QAGOMA Foundation Annual Dinner. The QAGOMA Foundation is the primary fundraising body of the Gallery.

#ArthurBoyd #QAGOMA