Though not a painting of a named sitter, George Washington Lambert’s Portrait group (The mother) 1907 (illustrated) nevertheless belongs to that category of art — Edwardian salon portraiture — which flourished in England in the first decade of the twentieth century. These were works especially characterised by flamboyance and bravura, where old master techniques were combined with a freshness that was distinctly modern, and they disappeared,along with the elegant and unhurried lifestyle they depicted, with the arrival of the First World War.1

Portrait group (The mother) is one of a series of works that feature the artist’s wife, Amy, and their children, Maurice and Constant. It is also one of several works, which include Lambert’s friend and colleague, the artist Thea Proctor.

RELATED: Thea Proctor

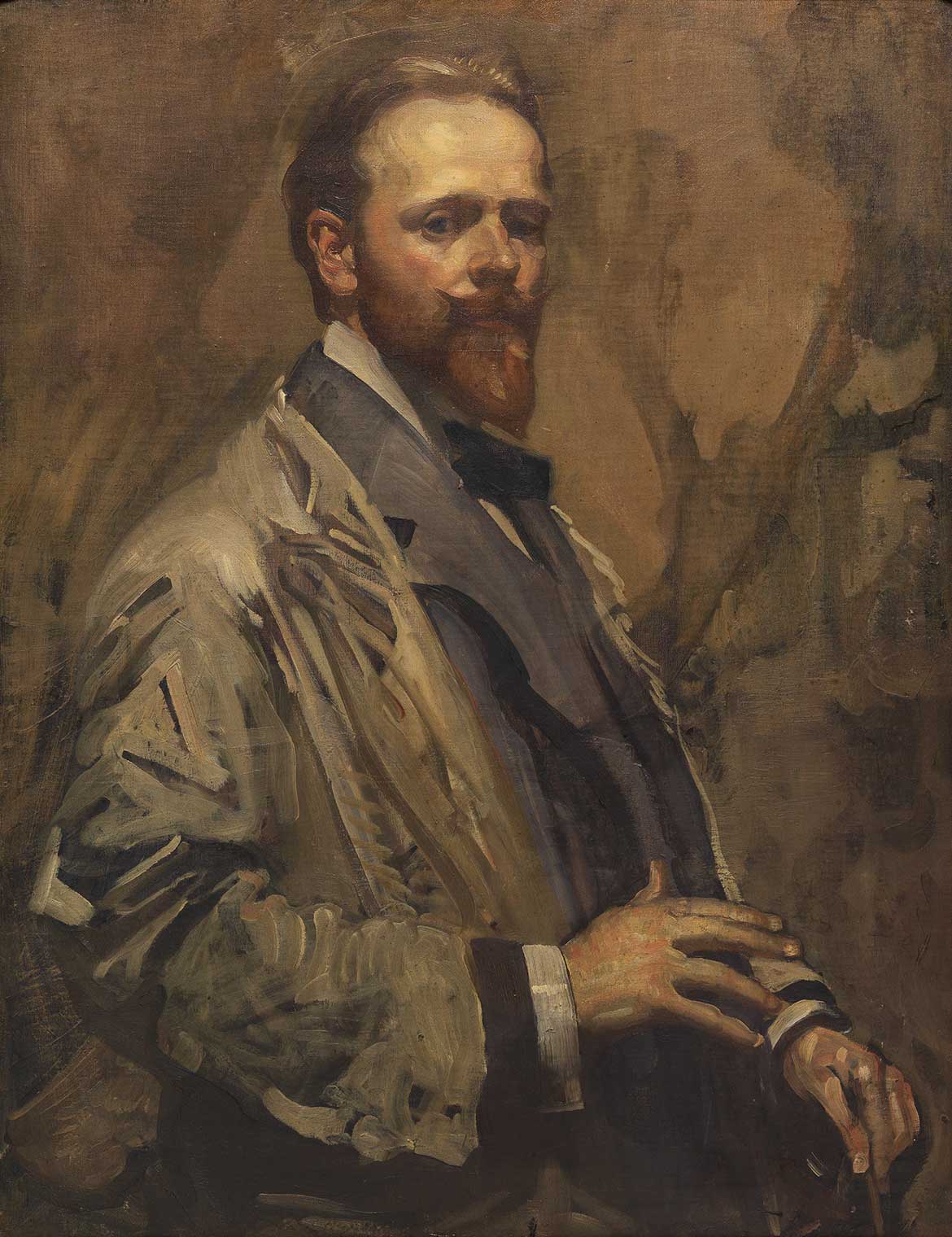

George W Lambert ‘The artist and his wife’

George Lambert met his future wife Amy Abseil in 1898 while he was studying at Julian Ashton’s Sydney Art School with her sister Marian. Amy worked as a retoucher at Falks, the photographers, and had aspirations to write. In May 1899 Amy published two short stories in the Australian Magazine, the short-lived journal started by several Sydney artists including Lambert, Thea Proctor and Sydney Long as a rival to the Bulletin.2 While not quite a suffragette, Amy was nevertheless rather anti-establishment, particularly so for the times. Tall, thin and elegant, she was given to wearing large, flamboyant hats; her dark eyes and hair and high cheek-bones giving her beauty an exotic, almost mysterious quality.

George W Lambert ‘Self portrait (unfinished)’

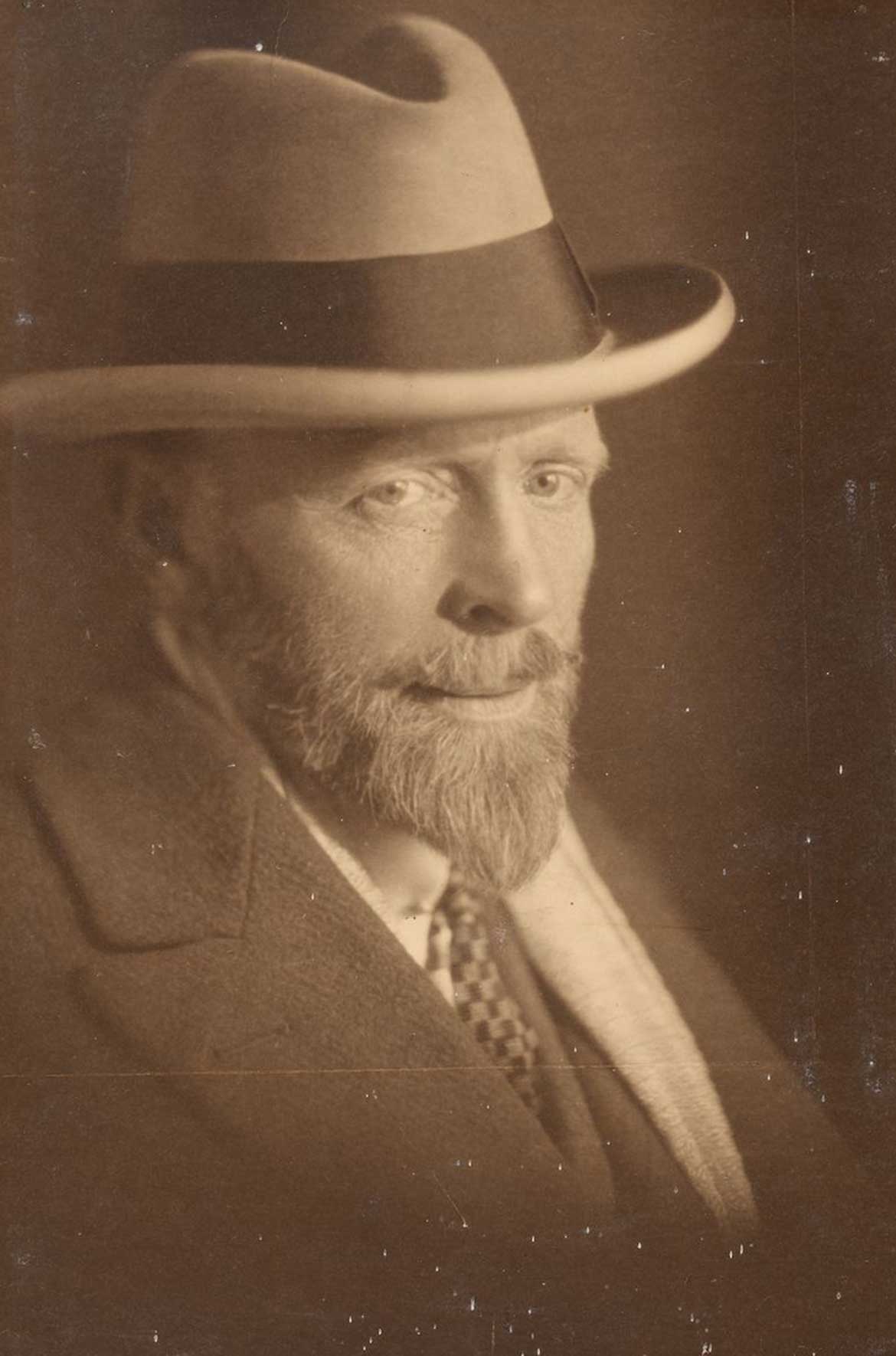

George, in contrast, was blond and blue-eyed — a ‘job-lot Apollo’ according to his friend W. B. Beattie. His energy was like that of a comet, Amy wrote, but with a touch of remoteness, as if he were above other people, a quality she found particularly attractive.3 He had a ‘fine, baritone voice’ and a flamboyant personality; something of a dandy, even in the midst of the most dire poverty he would maintain a sartorial presence.4 He had little desire for an ordinary life and neither did Amy. She idolised him from the beginning and remained absolutely devoted, despite years of neglect and then widowhood, until her death at the age of ninety-two.

Two days after they married in 1900, the Lamberts set off on board the SS Persic for England. They went immediately to Paris where Lambert and his friend Hugh Ramsay studied at Colarossi’s studio. Their life was spartan as they tried to eke out a living from the proceeds of Lamberts Bulletin money and the last of his NSW Society of Artists’ Travelling Scholarship. After the birth of Maurice in June 1901, the circumstances of their lifestyle became intolerable and they returned to London so that George could seek portrait commissions to improve their income. Amy coped well with their continual need for money, perhaps as a result of her working-class upbringing, often doing the hard domestic work that a servant would normally have carried out.

George W Lambert ‘On the Strand’

Though continually struggling to make ends meet, the Lamberts moved in a large circle of artists, musicians and writers and led an active social life that revolved around activities such as the annual Chelsea Arts Club Ball.5 George organised tableaux vivants, pageants and costume balls during this period and revelled in the theatricality of it all. As his biographer Anne Gray has stated, his paintings are frequently the pictorial equivalent of these performances in which artifice played a necessary role.6 George also supplemented their income by giving horse-riding lessons in Hyde Park and doing book and magazine illustrations.7 Always a good draughtsman, he now honed his drawing skills to a point few artists reached and is deservedly known now as much for his drawings as his paintings. Two such works are On the Strand 1909 (illustrated) and The simpler life 1905 (illustrated) — the latter a portrait study of Thea Proctor — and would seem to confirm the generally held view that it is in these simpler sketches that Lambert best caught the expression of the sitter.

George W Lambert ‘The simpler life (portrait study of Thea Proctor)’

George W Lambert ‘The three sisters’

In the summer of 1903 Thea Proctor re-entered the Lamberts’ lives. She had come to London to study and both George and Amy greeted her warmly and compassionately, understanding at once her homesickness and loneliness. She became a daily visitor to the Lambert household, taking tea with them and sharing visits to concerts and the theatre. At first she visited both husband and wife, until Amy began asking if they had to see ‘quite so much of Thea’. Soon she began to sit for Lambert in his studio. At 24, Thea was six years younger than Lambert (Amy was one year older). An elegant young woman from a solid country background, she was child-free and freespirited — a younger version of his wife — and was, in addition, as obsessed with art and art-talk as Lambert himself. She soon developed a habit of coming and going from both studio and house as she liked. In August 1905 a second son, Constant, was born and Amy became totally taken up with the childrens welfare.8 As their small flat was now very crowded, Lambert took a studio in Chelsea where he spent most of his time.

RELATED: George Lambert’s war compositions

George W Lambert ‘Kitty Powell’

As Lamberts career as a society portraitist grew, he was busier and busier, and Amy threw herself completely into motherhood, a role she truly relished. A distance developed between husband and wife, reinforced by the nature of Lambert’s social and professional life which, as often as not, excluded women. In 1906, for example, he had joined the all-male Modern Society of Portrait Painters and many evenings were spent socialising with expatriate artists Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton and George Coates, as well as the British painters. By 1907 Lambert was earning a sizeable income from his society portraits, thus enabling him greater freedom outside the home.9 The household became a complex one of competing egos and it is this domestic drama that Lambert — subconsciously perhaps — has painted in Portrait group (The mother).

George W Lambert ‘Portrait group (The mother)’

Portrait group (The mother) depicts Amy in a billowing cream silk dress, her hat in hand and her hair tied casually behind. She seems to be a woman totally at peace with her life and with her role as the mother of the two small boys.10 Thea Proctor, her arm placed lightly on Amy’s shoulder, is dressed much more formally and wears a large, plumed hat. The two women, leaning towards each other in a fond embrace, are represented very much as equals, though quite differently and subtly distinguished as the maternal woman and the professional woman. The older boy, Maurice, stands independently of the two women and stares at the artist, in a pose reminiscent, as Anne Gray identifies, of several well-known seventeenth-century portraits.11 The baby, dressed in luxuriant cream silk taffeta, all but merges with his mother, to whom he clings.

The composition, an unbalanced triangle, constantly forces the eye’s attention back to the face of the mother. The rich effects of silk, taffeta, feathers, lace, ribbons and velvet effectively conjure an impression of an earlier period and resulted from Lambert’s study of the work of Velázquez. Lambert’s friendship with Hugh Ramsay, when both were students in Paris, also reinforced his interest in the problems posed by the use of white-on-white. It is the technical mastery achieved in the handling of colour and texture that makes Portrait group (The mother) one of Lambert’s best.

Lambert also achieved a dazzling boldness through silhouetting his models in front of a pale blue and white sky, a technique he used in most of his major paintings. As he wrote in his unpublished autobiography, he was interested in Revivalism, in finding a way to combine the traditions of the great masters of painting with a modem technical proficiency.

Edited extract from ‘Family and a special friend: George Washington Lambert Portrait group (The mother)‘ from Brought to Light: Australian Art 1850-1965, Queensland Art Gallery, 1998. Dr Candice Bruce is former Curator, Australian Art, QAGOMA.

1 See Andrew Wilton, The Swagger Portrait: Grand Manner Portraiture in Britain from Van Dyck to Augustus John, 1630-1930 [exhibition catalogue], Tate Gallery, London, 1992.

2 Andrew Motion, The Lamberts: George, Constant & Kit, Chatto & Windus, London, 1986, p.28.

3 Amy Lambert, The Career o f G. W. Lambert, A. R. A.: Thirty Years of an Artist’s Life, Society of Artists, Sydney, 1938, p.25; reprinted by Australian Artist Editions, Sydney, 1977.

4 At his death, George Lambert’s estate listed great quantities of clothes amongst his possessions (see Lambert Papers, MSS 97/13, Mitchell Library, Sydney).

5 Amy’s father, Edward Abseil, had migrated from London in the 1890s to Sydney hoping to continue his work as a cooper. Shortly after their arrival, however, he lost all his money (see Motion, p.31).

6 See Anne Gray, George Lambert 1873-1930: Art and Artifice, Craftsman House, Roseville East (NSW), 1996, p.59.

7 Motion, p.49.

8 Baptised Leonard Constant, the Lamberts’ second son was always called by his middle name.

9 See Gray, George Lambert 1873-1930: Art and Artifice, p.42. Gray contexts Lambert’s art particularly well in relation to the work of his British contemporaries, especially William Strang, Glyn Philpot and Augustus John.

10 It is not surprising to know that, of all the family portrait groups, this work was Amy Lambert’s favourite (see Anne Gray, George Lambert 1873-1930: Catalogue raisonné, Bonamy Press in association with Sotheby’s and the Australian War Memorial, Perth, 1996, p.23).

11 Gray, George Lambert 1873-1930: Catalogue raisonné, pp.22-3.

Portrait of George Lambert

Featured image detail: George W Lambert Portrait group (The mother) 1907

#QAGOMA