Australian artist Ah Xian has been awarded the 2019 Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Medal in recognition of his enduring and impassioned contribution to the Gallery. We honour and celebrate the highly acclaimed artist and benefactor for his outstanding contribution to the QAGOMA Collection. His sustained and exceptional patronage places him among our most generous donors.

A self-taught painter, Ah Xian began his career as a professional artist in the early 1980s, when his work was included in group exhibitions in his hometown of Beijing. He first came to Australia in early 1989 as a visiting scholar to the University of Tasmania’s School of Art, returning to Beijing only weeks before the violent and fatal confrontation in Tiananmen Square, which he witnessed. This deeply traumatic event prompted Ah Xian to settle permanently in Australia the following year, and informed much of his subsequent work — not least his 1991 ‘Heavy wounds’ series, a large part of which he gifted to the Gallery in 2012, following several previous private gifts from the series.

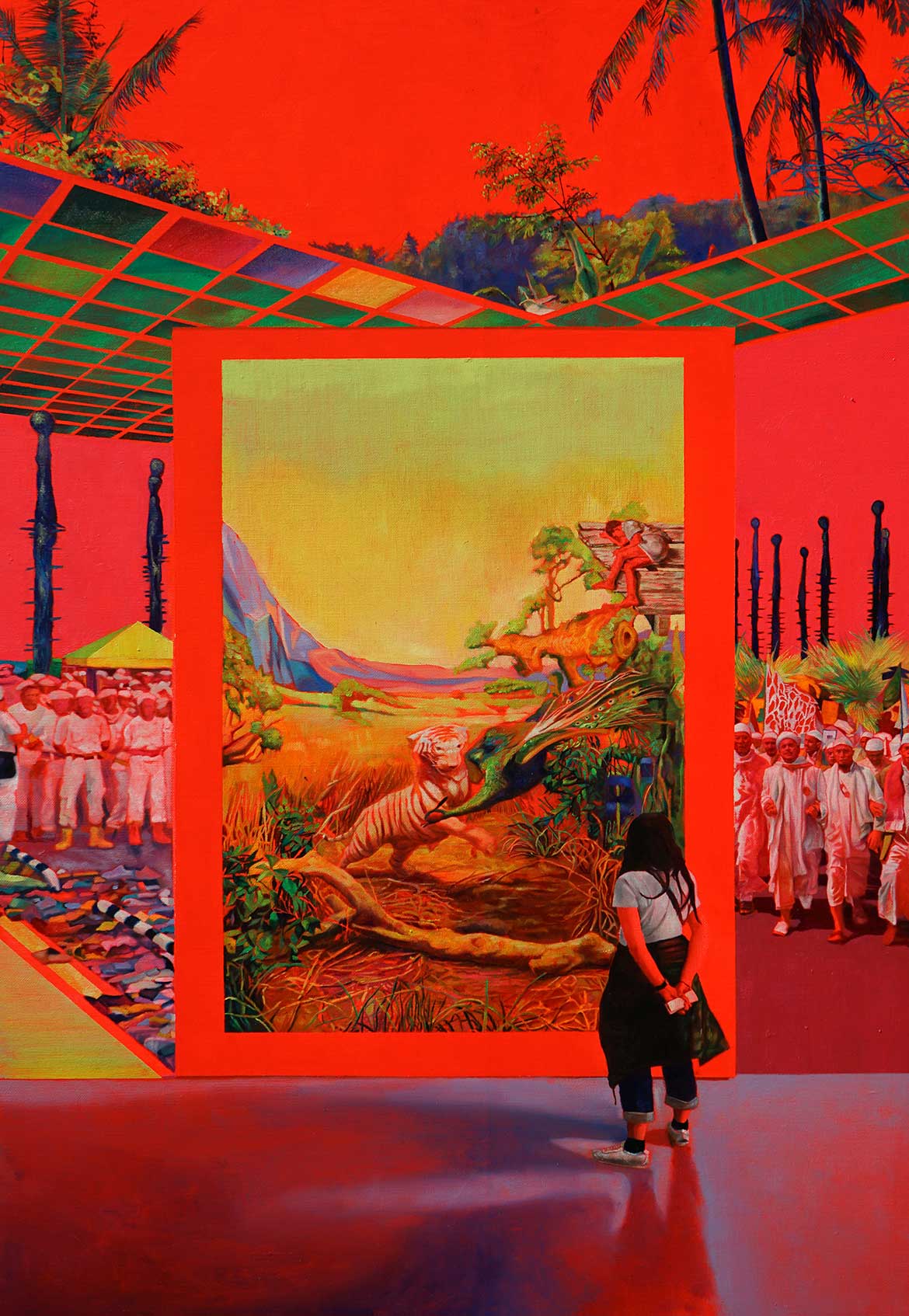

‘Human human – lotus, cloisonné figure 1’ 2000-01

In a conscious attempt to reconcile his heritage with life in his new country, Ah Xian began working with traditional Chinese materials such as bronze, jade, lacquer and cloisonné, applying contemporary innovations and approaches to his exploration of traditional cultural motifs and processes. The results constitute one of the most materially and aesthetically refined bodies of work in our contemporary Asian art collection.

Ah Xian’s deep engagement with this Gallery began with the inclusion of exquisite porcelain busts from his ‘China, China’ series in ‘Beyond the Future: The Third Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (APT3) in 1999. In 2003, the Gallery staged a solo exhibition of Ah Xian’s works, featuring the life-sized sculpture Human human – lotus, cloisonné figure 1, a celebrated work that won the inaugural National Gallery of Australia’s National Sculpture Prize in 2001 before entering the Collection.

An extraordinary group of 36 bronze busts titled ‘Metaphysica’ featured in ‘The China Project’, presented at the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) in 2009, and a group of these also toured regional Queensland, visiting 14 venues between 2013 and 2015. While the busts were touring the state, an exhibition of early paintings — ‘Ah Xian: Heavy Wounds’ — was curated for the Queensland Art Gallery (QAG) in 2014. Two years later, the Children’s Art Centre, GOMA presented ‘Ah Xian: Naturephysica’, an interactive project developed with the artist, which invited children and families to engage with his ideas and techniques. Currently, Human human – lotus, cloisonné figure 1 and several sculptures from the ‘China China’, ‘Human human’ and ‘Metaphysica’ series are a central feature of QAG’s Philip Bacon Galleries.

Not only is Ah Xian an accomplished artist and generous donor, but the beauty and resonance of his practice has motivated others to support the Gallery. Many more works by Ah Xian have joined the Collection with the assistance of benefactors such as Tim Fairfax AC, the Myer Foundation, Carrillo Gantner AO and Ziyin Gantner, Nicholas Jose and Claire Roberts, and the Dines Family. In itself, this is a further measure of the respect and admiration for Ah Xian’s work.

Ah Xian is the first artist to receive the Gallery Medal. Its previous recipients include former Chair of the Board of Trustees Richard (Dick) Austin AO OBE (1919–2000) who established the Asia Pacific Triennial; major donor and philanthropist Winifred (Win) Schubert AO (1937–2017); longstanding volunteer guide and donor Pamela Barnett; major donor and long-term Foundation Committee member James C. Sourris AM; and major donor Cathryn Mittelheuser AM.

In 2019, the Queensland Art Gallery Board of Trustees and I are very pleased to award the QAGOMA Medal to Ah Xian in acknowledgment of his enduring and inspiring contributions to our institution.

Chris Saines CNZM is Director, QAGOMA

Feature image: Ah Xian awarded the 2019 QAGOMA Medal / Photograph: M Grimwade

#QAGOMA