I am delighted to unveil our plan to transform Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art’s ‘white box’ into a monumentally-scaled solid light wall. Part of the architects’ design concept by Architectus + Davenport Campbell lead architects Kerry Clare, Lindsay Clare and James Jones was for GOMA to have an artist-illuminated ‘white box’ on the building’s eastern and southern glass facades.

While that vast 1200 square metre container for light was built – using some two hundred 4 x 15 metre panels of translucent Starphire glass, set out from the interior to act as a diffuser – it remained determinedly unlit.

THIS PROJECT AT QAGOMA WILL GIVE NEW LIFE TO COMPLETING THE EXPRESSION OF THE BUILDING’S PERSONALITY AT NIGHT.

JAMES TURRELL

To realise that far-sighted and luminous vision – we can now announce one of the world’s most renowned artists James Turrell (United States, b.1943) has been engaged to create a new work in his Architectural Light series.

I HAVE ALWAYS WANTED TO GIVE LIFE TO BUILDINGS… TO CLOAK THESE STRUCTURES IN A BEAUTIFUL RAIMENT OF LIGHT.

JAMES TURRELL

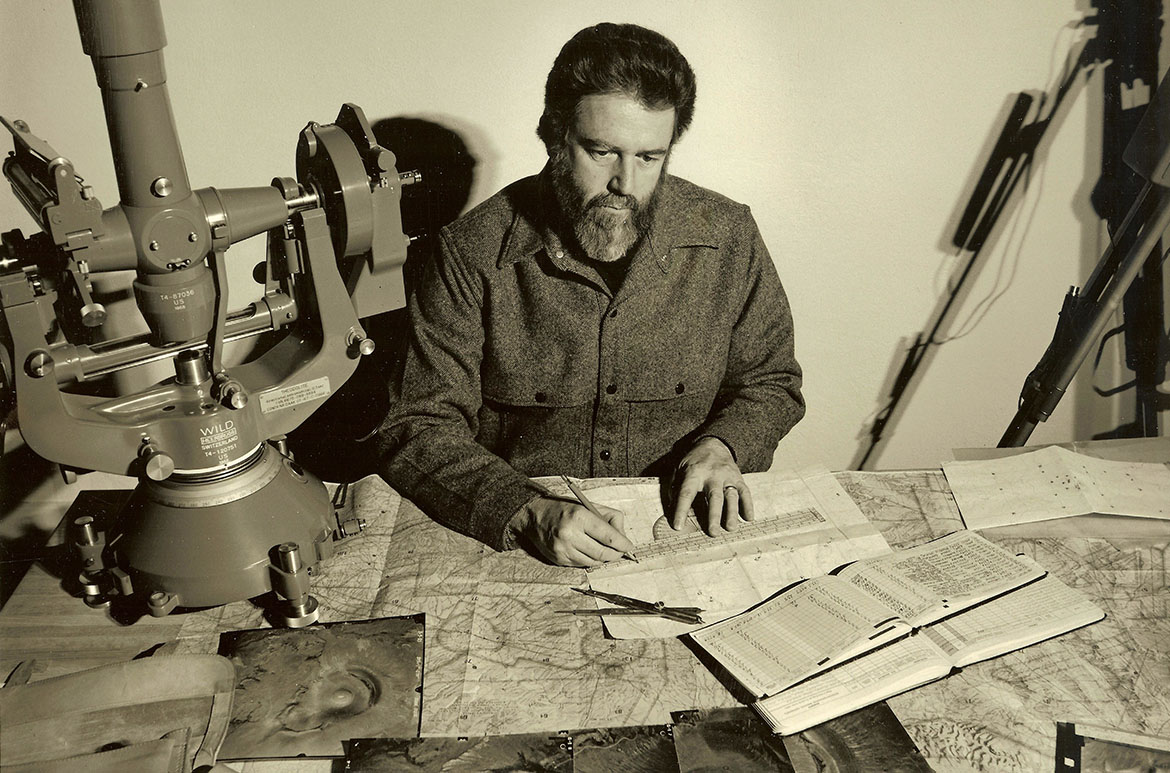

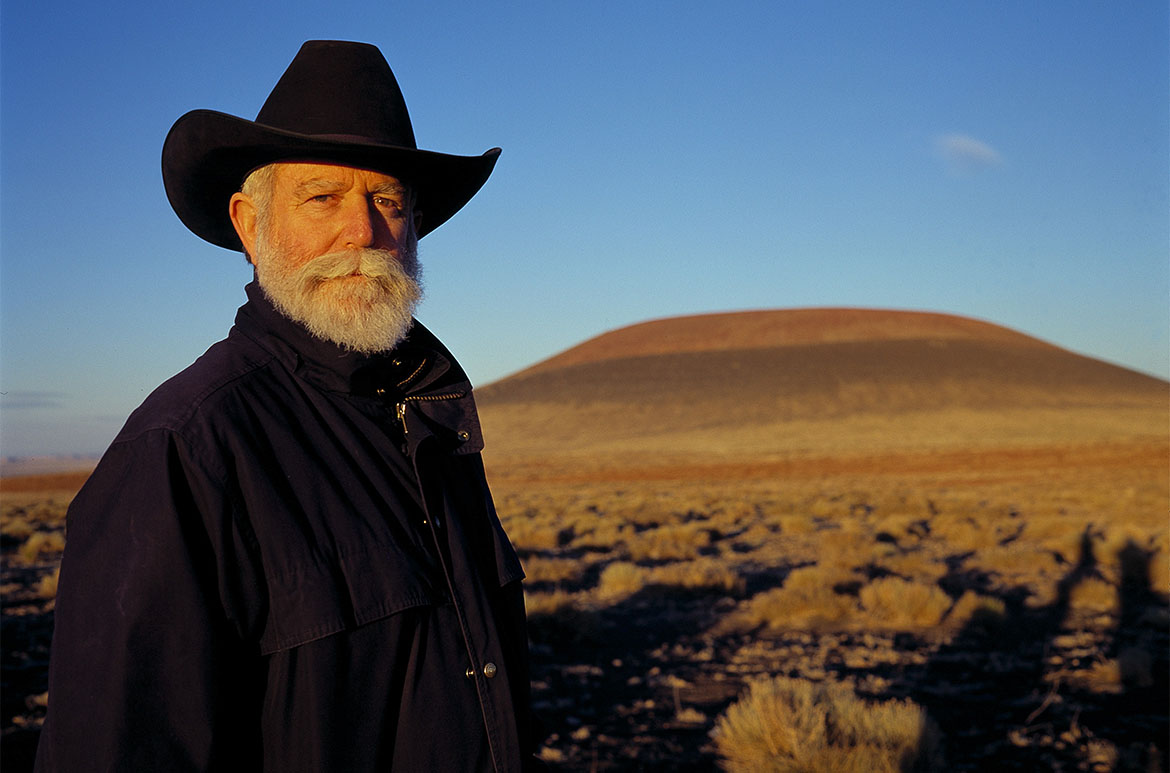

Raised a Quaker – a practical theology that seeks pathways to the light of God – Turrell’s father was an aeronautical engineer and a school administrator, and his mother a doctor who at one time worked in the Peace Corps. He obtained his pilot’s licence aged 16 and has spent much of his life flying fixed-wing planes and gliders; a passion that echoes within the limitless horizons and confounding perspectives of his installation work.

Beginning with his earliest Projection Pieces, Turrell has spent 50 years considering our response to the materiality of light experienced in space and through time. He asks us to examine the nature of our looking and our seeing.

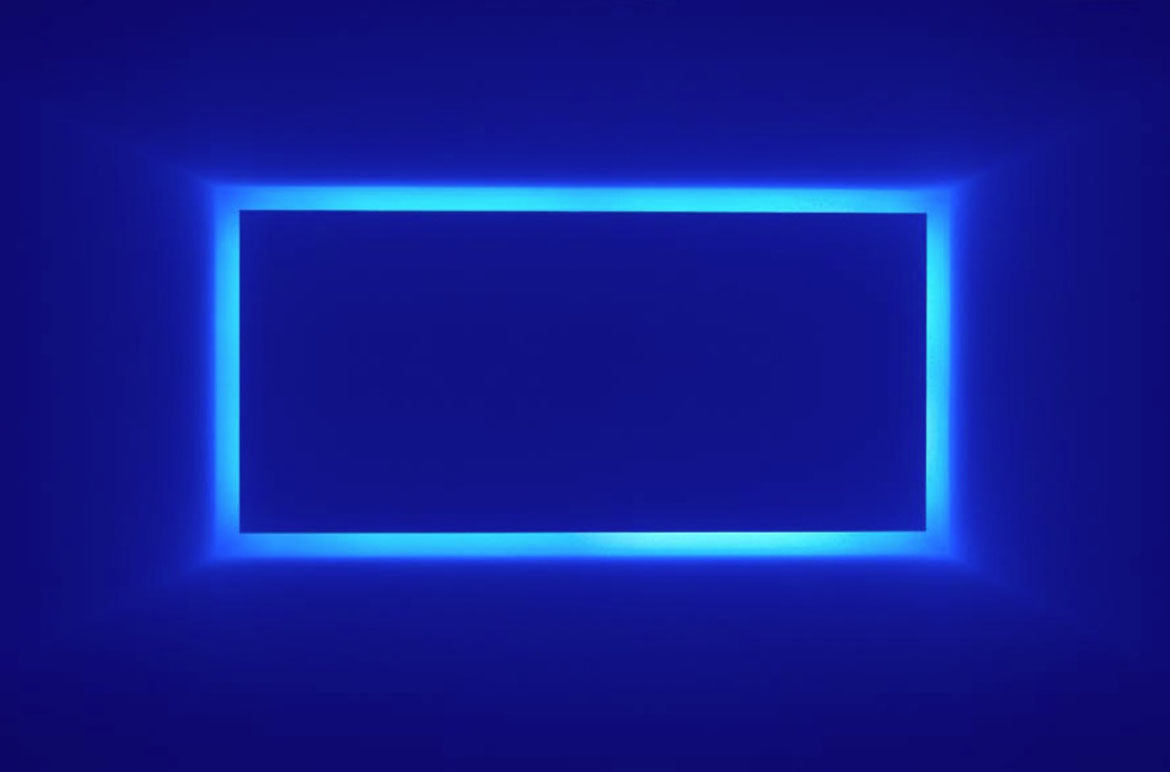

He works with man-made light– as in Rondo (Blue) 1969, in Houston – and with natural light, drawing attention to the light of the world through elegantly constructed apertures. His works occupy public spaces that are meticulously designed to cultivate a spirit of contemplation and private reflection – a moment of shared quietude in the company of others. They imperceptibly slow the passage of time.

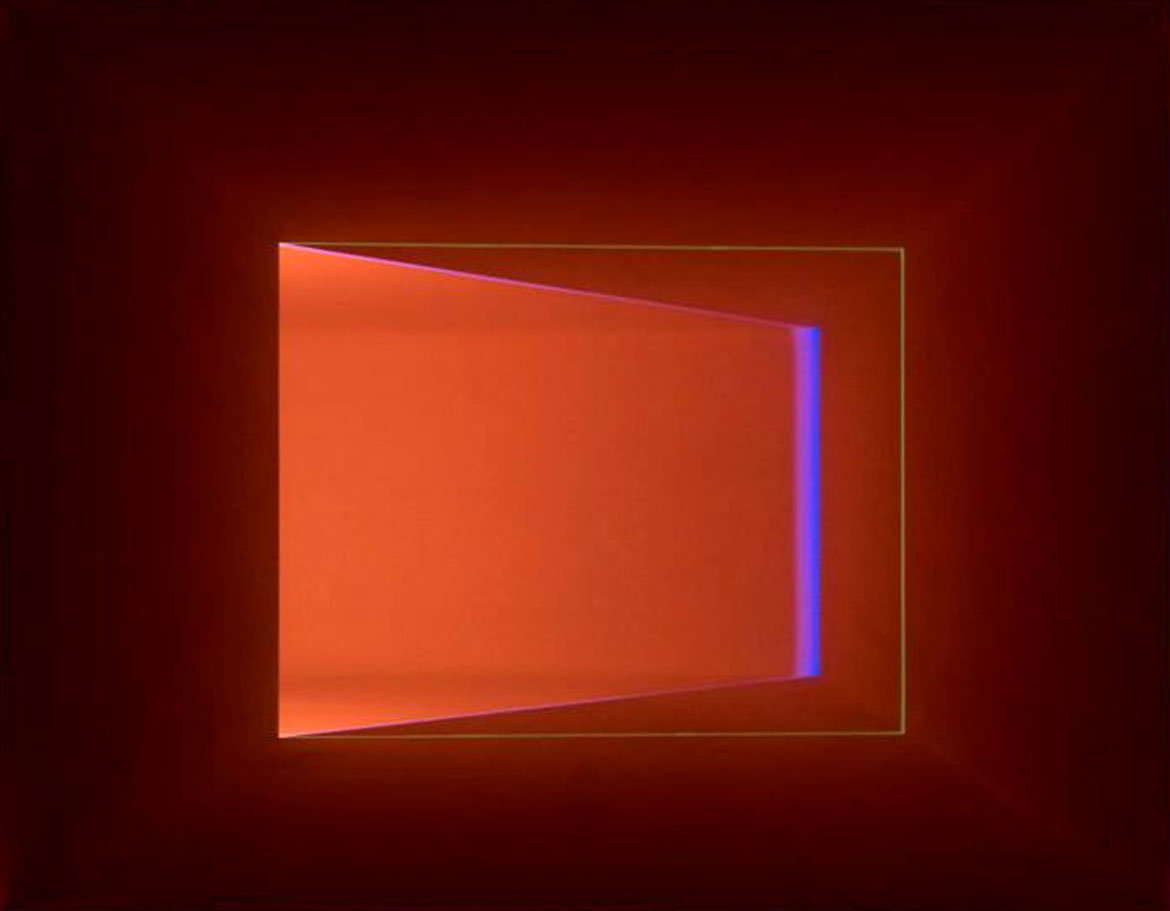

For all his reliance on minimalist means, most notably in his Wedgeworks series, Turrell shapes projected light to create the unerring illusion of three-dimensional space, in a manner not unlike painting itself. In Caravaggio’s Calling of St Mathew 1599-1600 – as blindingly contemporary in its day – Christ’s entry into a tavern stands in symbolic parallel to the entry of light which transcends the mere elaboration of pictorial space. In both, light is dramatically arranged for patently common purposes: to enable us to bear witness to remarkable events; to apprehend space where none actually exists, and to create a space for revelation to occur.

Turrell’s Wedgeworks serve to demonstrate his long-standing interest in the “…thingness of light, its object-making, thing-making kind of ability.” The act of looking attentively at these works reveals light made manifest as an object in and of itself, rather than as an agent of material description.

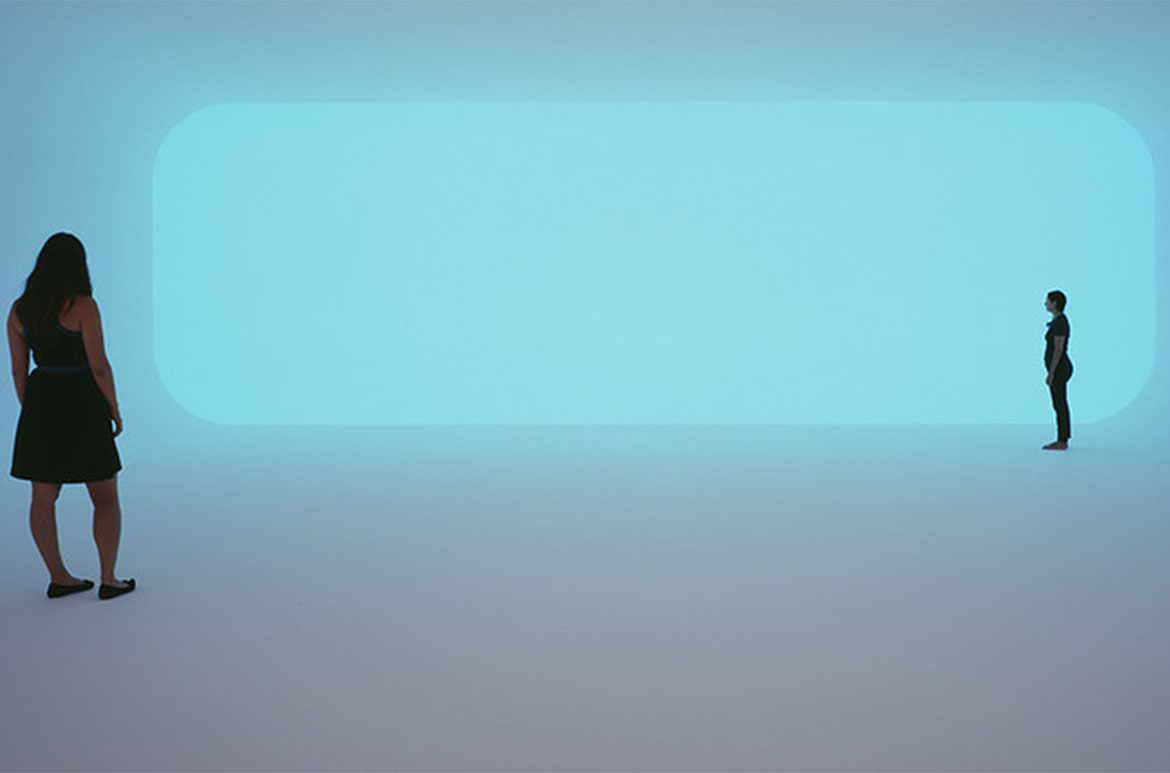

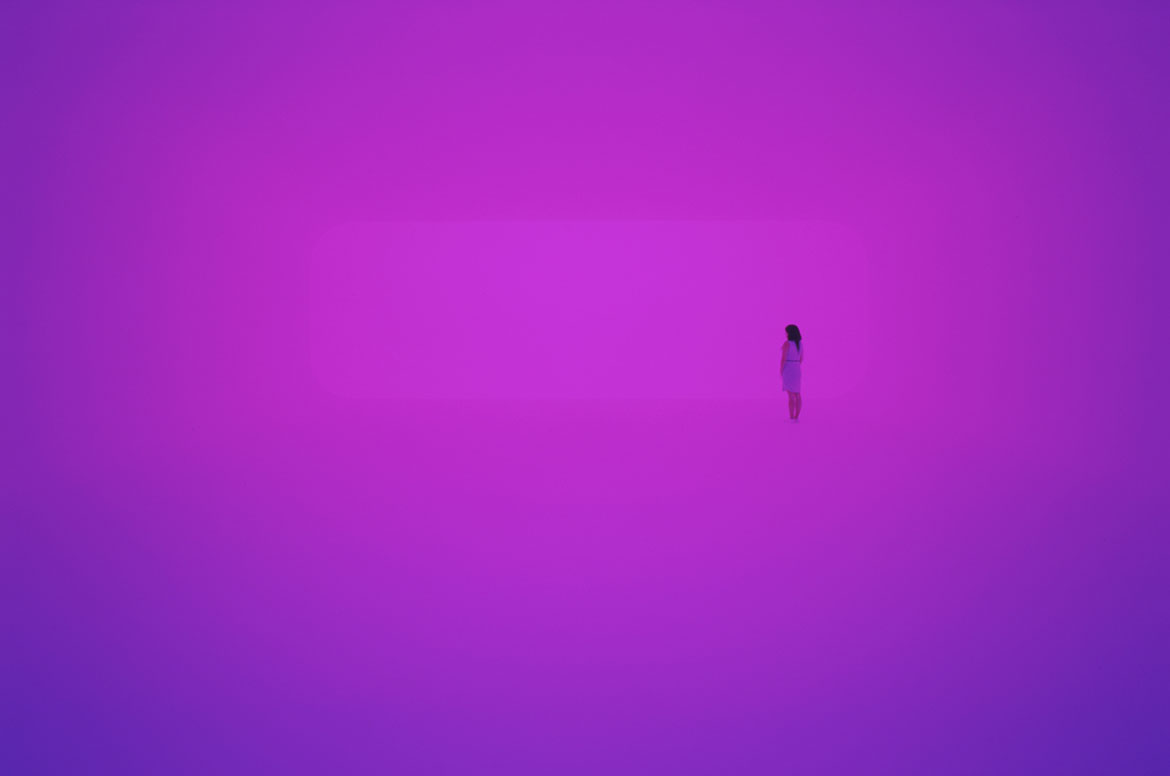

In his Ganzfeld series – a German word to describe the phenomenon of the total loss of depth perception, as in the experience of a ‘white out’ – Turrell invites the viewer to physically, cognitively and emotionally enter the light space of the work; to enter through the picture plane, as it were.

“Early on”, he recounts, “I was struck by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s description of flight spaces…, spaces within space, not defined physically by the architecture of form but by pressures within the atmosphere… [I was] interested in the idea of the journey into these spaces…”

The colour of light in a Ganzfeld is constantly, imperceptibly shifting through time and space, un-anchoring us from our ground-based view of the world. For Turrell, the avid pilot, it’s a “differentiation of vision [of a kind that] happens through weather and water vapour”.

While Ganzfeld works like Breathing Light 2013 set up the dual conditions of a sublimely social as well as a dream-like experience, Turrell’s trenchantly utopian Perceptual Cells can only be experienced one viewer at a time. Lying face-up on a sliding support held in a completely enclosed orb-like space for five or so minutes, the solitary viewer’s every sensory receptor is assailed by what I can only describe as ‘light you can feel’. Perhaps it comes closest to fulfilling Turrell’s long-held desire to “…make a light that looks like the light you see in your dreams.”

By contrast, it’s an earth-bound light that is held via the cone of this long extinct volcano – Roden Crater – on the edge of Arizona’s Painted Desert north of Flagstaff, which Turrell found after a vast aerial search in 1974. Roden Crater Project (1979 –) is a monumental land-based work of art that will, when complete, form a naked-eye observatory into which he has very precisely inserted access passageways and subterranean viewing chambers.

When seen from the bottom of the crater, its nearly circular dish-shaped bowl – made more so by colossal levelling and grading works – accepts and amplifies the optical and visual effects of celestial vaulting. Multi-level viewing portals are strictly oriented toward events observed in the sky, enabling a direct and profound experience of the sun, moon, and stars, and with it an apprehension of our place within the cosmos.

One tunnel, which impels your eye toward a distant viewing chamber, is designed to frame the moon at a point of astronomically precise alignment. By isolating and occluding light from events not being looked at, Turrell intensifies and profoundly expands our understanding of solar and lunar light.

In 2013, James Turrell was granted an unparalleled honour for an American artist; concurrent exhibitions at the Guggenheim Museum in New York; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art; and the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston. Among several major new works was Aten Reign 2013, which was formed out of the admixture of LED fittings and the natural light that falls through an oculus, a circular opening at the top of Frank Lloyd Wright’s spiral rotunda at the Guggenheim.

It was a phenomenal success, a brilliant reimagining of one of the city’s most iconic buildings, drawing in from the edges of the ramp to its interior volume and, for Turrell, producing “…an architecture of space created with light.”

It was at this moment the potential for GOMA to make its own artist-illuminated statement, within an iconic Brisbane building, became apparent, and Turrell was approached to create one of his Architectural Light works – which enliven major buildings around the globe.

I would like to light the building up from the inside… Light that comes from inside enlivens and gives life to a building.

James Turrell

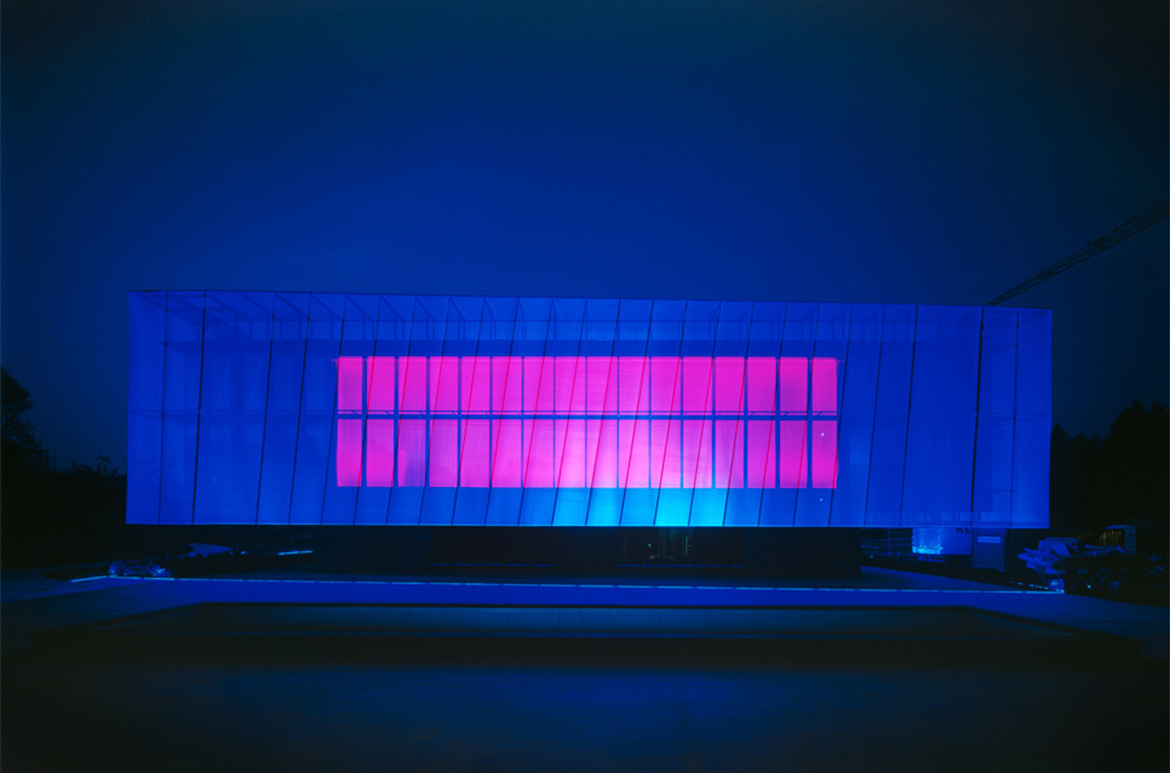

Once example of the series is FIFA Headquarters in Zurich, set in a vast wooded parkland and approached by the viewer across a bustling plaza. This project – like so much of the work for which Turrell is best known – vividly employs the low- energy-demand but astonishingly high chromatic intensity and resonance of contemporary LED fittings. This isn’t the kind of light conventionally projected through the night, only to strike then scatter off a solid built surface. It is a solid light, gathered within the architecture itself, which breathes out into the night.

The Queensland Government is joining with the Gallery’s Foundation to complete the original design intention for the building. Without the Queensland Government’s extraordinary support, a truly outstanding lead donation from Paul and Susan Taylor, and a generous contribution from the Neilson Foundation, an enterprise on this scale would have been impossible.

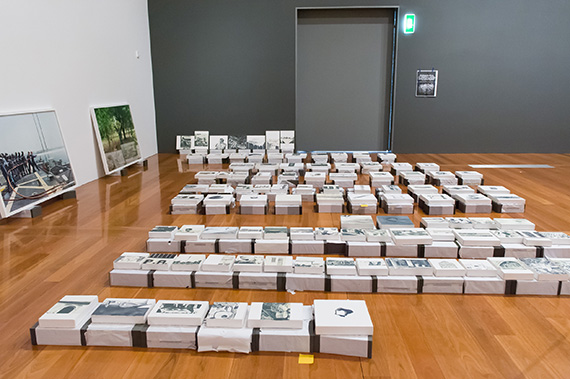

The 2017 QAGOMA Foundation Appeal was dedicated to bringing a long-dormant vision for the GOMA building to life some ten years after its opening. For the first time, the annual Appeal supported a truly public artwork that will be illuminated nightly, one in which the city and community can equally share.

I believe that buildings have a consciousness, and as long as they are inhabited and used, you feel that.

James Turrell

Know Brisbane through the Collection / Read about Australian art / Subscribe to QAGOMA YouTube to go behind-the-scenes

Chris Saines, CNZM is Director of the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA)

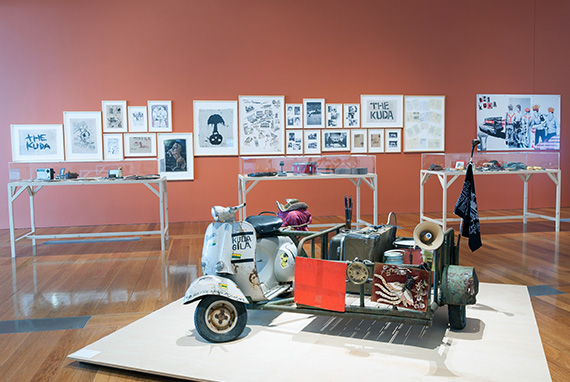

Feature image: Indicative image of James Turrell’s architectural light installation at the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA)

#JamesTurrell #QAGOMA