Kayili artists Mary Gibson, Mrs Kumana Ward, Pulpurru Davies, Nola Campbell and Jackie Kurltjunyintja Giles have each indulged a love of colour, animating their car bonnet’s surface with shimmering, cryptic, topographical maps of their country, and the ancestral journeys that formed it.

Patjarr, home to the Kayili artists, is a small community of around 20–30 people, situated 1,000 kilometres west of Alice Springs, Northern Territory, in the heartland of the Western Desert. The Kayili were amongst the last of the nomadic Indigenous desert peoples forced into settled life through government intervention. The first white people they encountered arrived by car in the early 1960s — an experience akin to having a spaceship land in the main street of your home town — and now many desert elders have their own car.

Pulpurru Davies ‘Toyota’

When you’re a few hundred kilometres by dirt road from anywhere and the bush abounds in delicious wildlife, owning a car makes sense. But with unsealed sandtracks in the vast Ngaanyatjarra desert lands, owning a car can lead to misery.

For the Kayili, the car is a desirable possession and takes up much time and energy. Cars are a vital part of desert life: life travels smoothly when they are running well and frustration sets in when they are not. Days and nights can be spent waiting on the side of the road for the next vehicle and the chance of help, and the search for tyres and fuel can be long. Then there are the family days: visiting relatives, attending football matches, collecting honey ants and chasing kangaroos (by crashing through the scrub), or travelling for sorry business. These trips are also a chance to recount tales of the journeys of known and much-loved motor cars.

A road journey through the desert can be a memorable experience: travelling ancient pathways, always fearing the consequences if protocols are transgressed. At times, convoys of people snake along rough bush tracks for men’s ceremonial rites. Roads are closed to the uninitiated, and no women are allowed. Following the faint image of a number plate on the car in front, drivers and passengers share the intense experience of night–time travel in overladen vehicles without headlights.

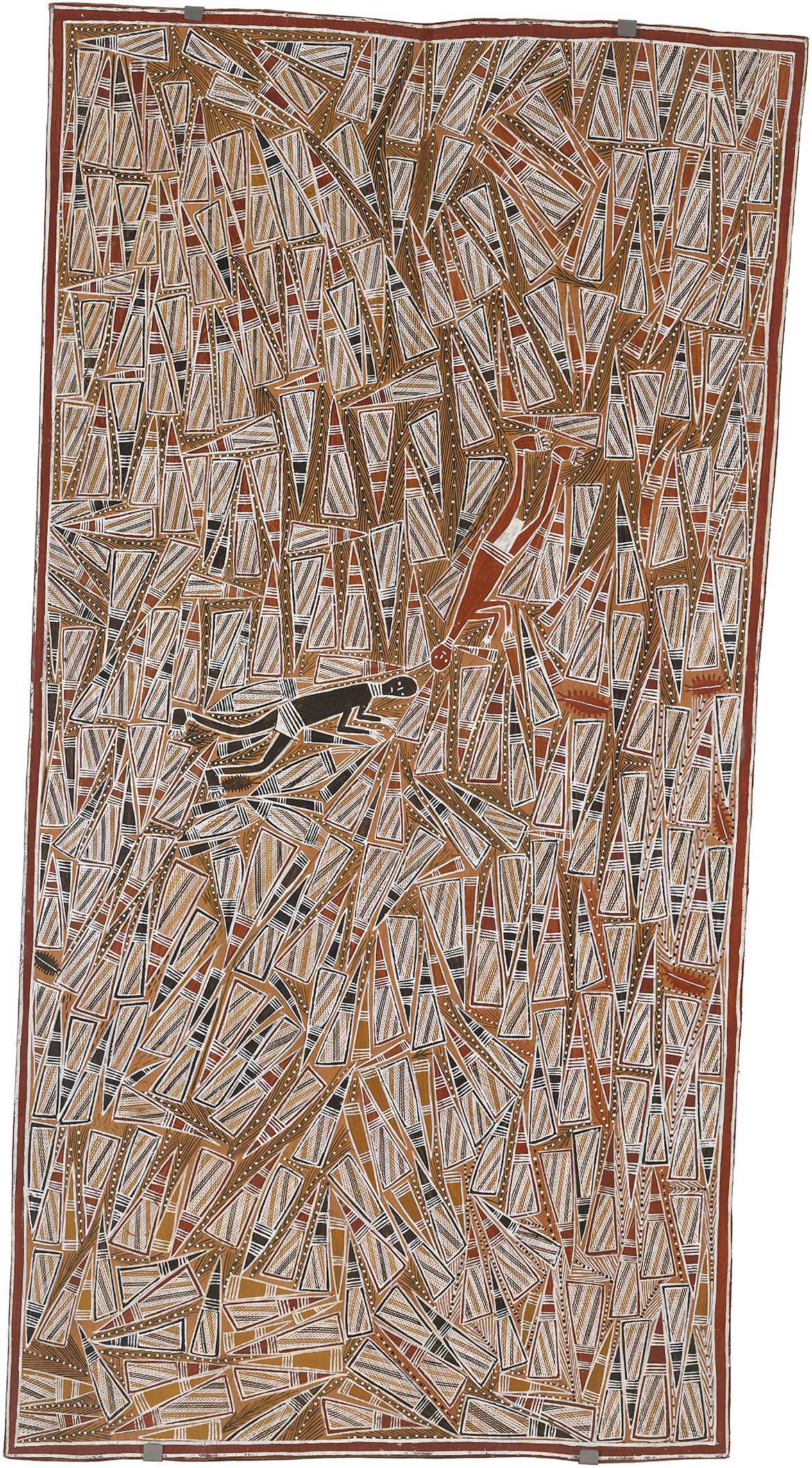

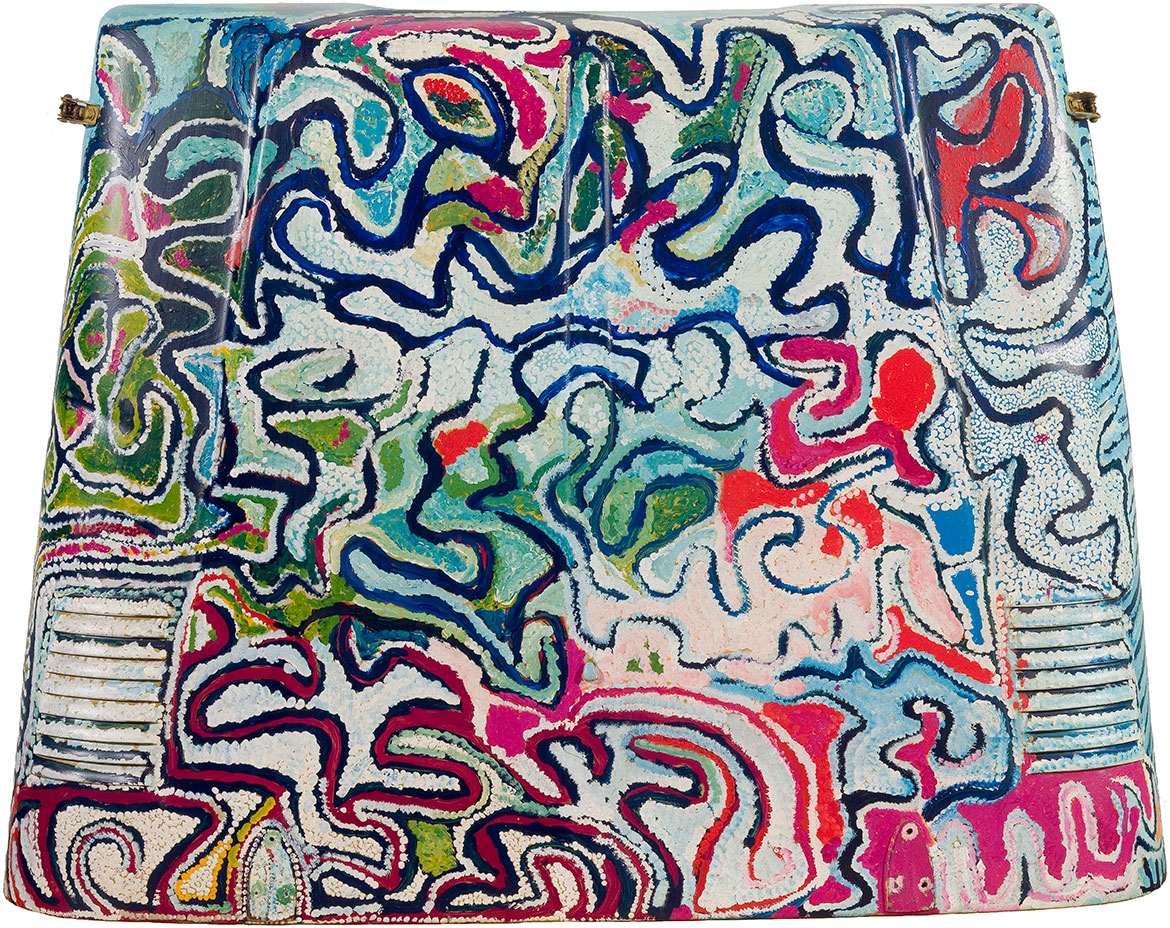

Jackie Kurltjunyintja Giles ‘Valiant’

Enigmatic images painted onto handy surfaces, such as rusted shipping containers, appear regularly in Patjarr. Lots of second–hand vehicles come to the desert (often bought with artists’ painting money); they die there and are abandoned. The Kayili artists saw these discarded motor cars as inviting surfaces on which to mark ancestral dreaming tracks. These five car bonnets have lain for years in the desert, half buried in red sand with the scent of seasonal bush flowers drifting over their surfaces. Preserved by the dry desert climate, and having escaped the occasional visits of a wrecker, they were retrieved from their shallow graves, cleaned of sand and rust, and primed for painting. The artists have indulged their love of colour in animating these unlikely surfaces with the shimmering, cryptic topographical maps of their country and the ancestral journeys that formed these lands. As Michael Stitfold from the Kayili Artists Cooperative commented:

Bonnets and people seemed to match up — there was the ideal bonnet for each artist. In some cases the artist knew its history: who owned it, when and where it had come from, its life at Patjarr.1

Jackie Kurltjunyintja Giles just had to have the formerly stylish Valiant (now riddled with bullet holes), rescued from the side of the road in South Australia and hauled back to Patjarr on a roof rack, while Pulpurru Davies chose the Toyota as she simply felt a connection with it.

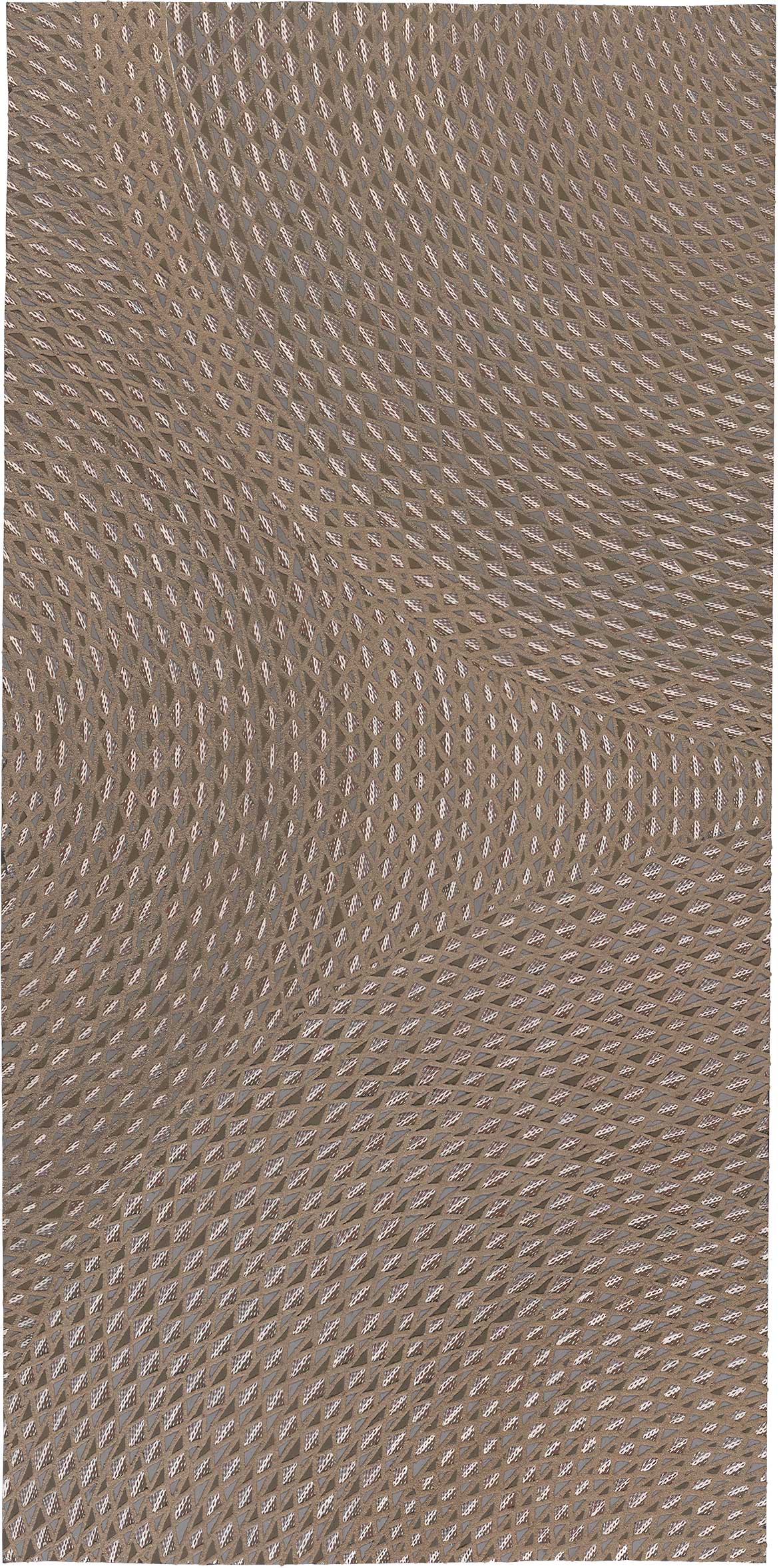

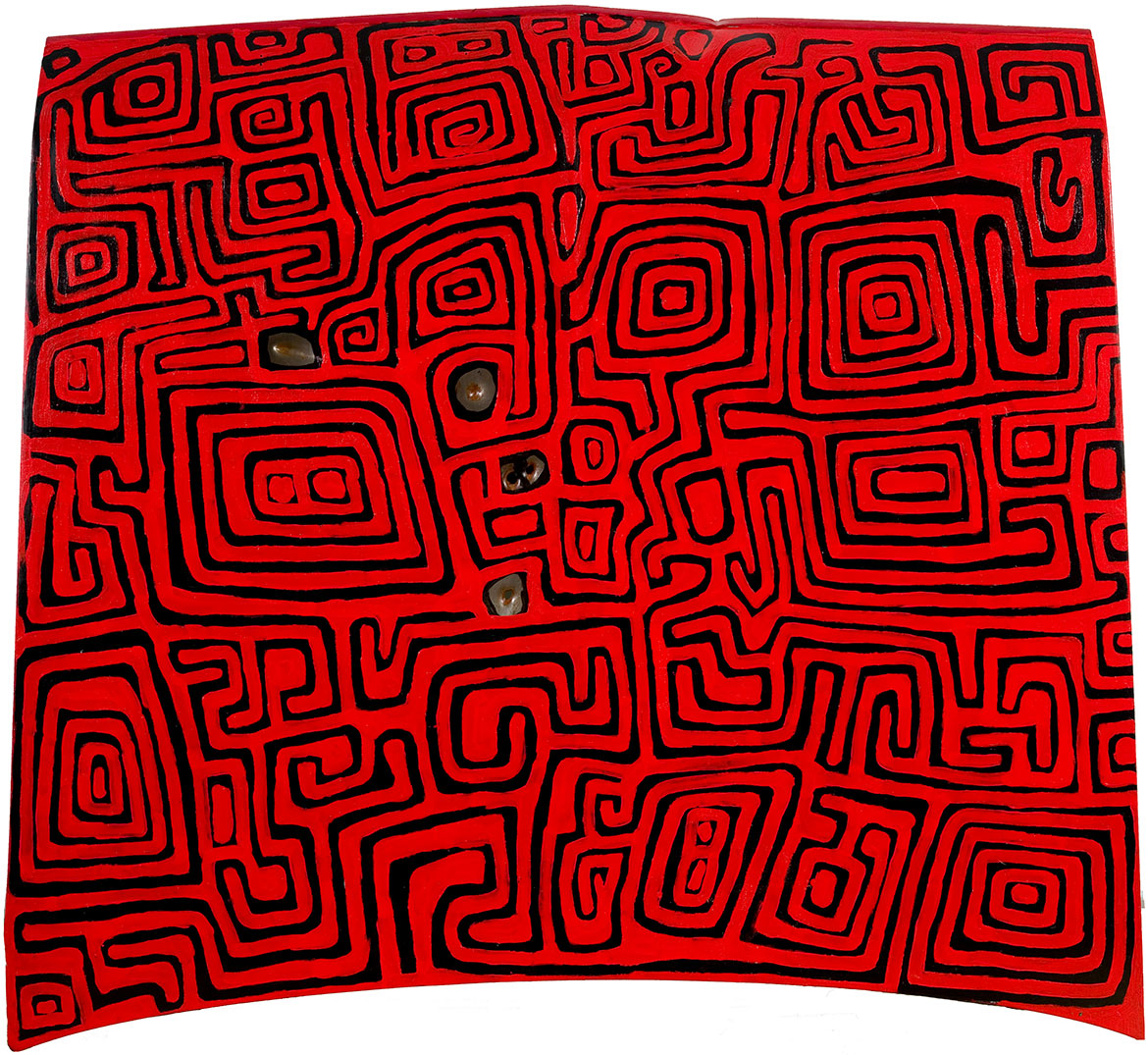

Mrs Kumana (Ngipi) Ward ‘Nissan’

Onto a Nissan car bonnet, Mrs Kumana Ward has painted a series of freshwater claypans, Murrman, Yirril and Patantja, which lie on the road to Banghor (the Canning Stock Route). Ward traces the sandhill landscape and its features in vibrantly coloured lines. As one of the greatest goanna hunters in the region, she knows these paths intimately and can survive in this country for days at a time.

Pulpurru Davies is highly regarded for her extensive cultural knowledge and here, in Toyota 2007, she depicts the story of Nyinangnya, a big walatu (saltpan lake) and an important soak water site north of Patjarr, where there are big kurrkapi (desert oak trees) and many rabbits to hunt.

Malu (kangaroo) is Jackie Kurltjunyintja Giles’s tjukurpa, or dreaming, and in Valiant 2007 he depicts the epic journey of the ancestral kangaroo. Malu came from the north to Tjamu Tjamu in Giles’s father’s country and camped there for a while with a group of women before travelling on to Tjutalpi, Witunkuntja, Wirti, Makarra and MiUmillpa. A rock hole at Tjamu Tjamu was named Kurril Kurril after the kangaroo spirit.

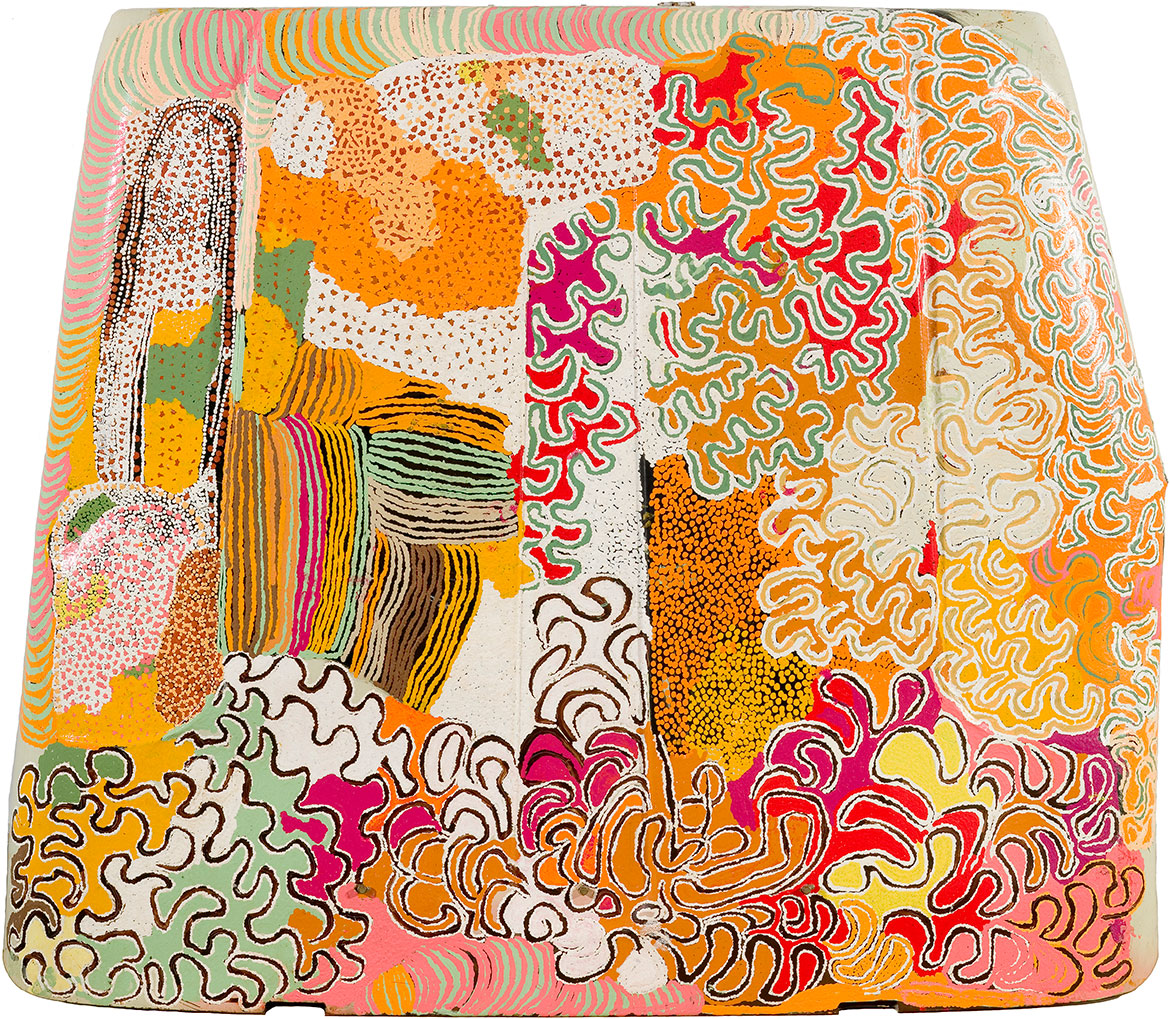

Nola Campbell ‘Holden’

Nola Campbell has painted Ngiyari, a female thorny devil, onto a Holden car bonnet. The Ngiyari ancestor created a route through the artist’s country, digging holes in which to deposit her eggs as she travelled. These holes remain as a series of freshwater wells, and include Kunangarra, a deep, underground hole where cool fresh water can be found.

Similarly, Mary Gibson has depicted the country around Kulkurda, which lies north of Tjukurla and south of Kintore. The large unpainted space on the Toyota HiLux bonnet is the soak water site called Nyinmi, which is the place of tjila (water snake). She has also painted tali pirni (many sandhills) and a big lake called Tuuwa, south of the sandhills.

These senior artists paint with an intensity that reflects their responsibility as bearers of tradition who constantly invent new ways to record their culture and portray their desert world. After working on comparatively bland fields of canvas, the undulating forms and rich textures of car bonnets have inspired works of strong visual impact. By recounting ancient travel tales, they create new stories for the cars (bullet holes and all) on the next stage of their journey. A beautiful irony exists in these painted wrecks now they are given new life, and travel back to the cities from which they came.

Diane Moon is Curator, Indigenous Australian Fibre Art, QAGOMA

Edited extract from ‘Kayili artists: Art and cars’ from Contemporary Australia: Optimism, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, 2008.

Endnotes

1 Michael Stitfold, telephone conversation with the author, June 2008.

Mary Gibson ‘Toyota HiLux’

Acknowledgment of Country

The Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the land on which the Gallery stands in Brisbane. We pay respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders past and present and, in the spirit of reconciliation, acknowledge the immense creative contribution First Australians make to the art and culture of this country.

It is customary in many Indigenous communities not to mention the name or reproduce photographs of the deceased. All such mentions and photographs on the QAGOMA Blog are with permission, however, care and discretion should be exercised.

Featured image detail: Mrs Kumana (Ngipi) Ward Nissan 2007

#QAGOMA