Amata community is located in the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) lands in north-western South Australia. In the 1970s, Amata women were encouraged to learn batik, natural dyeing, spinning, weaving and leatherwork techniques. Minymaku Arts (meaning ‘belonging to women’) was set up in 1997, but in 2005 the centre was renamed Tjala Arts, with both men and women painting abstract imagery adapted from traditional symbols and concepts.

Tjala Arts is now a hub of activity in the Amata community and a leader in the vibrant Western Desert painting movement reinvigorating contemporary Australian art. The art centre is a roomy industrial shed with a high, raked roof, keeping it fairly cool, though conditions can be extreme. The centre is adjusted for temperature, however, so that the artists can work in comfort. On an attractively paint-spattered cement floor, on vinyl-covered cushions, the women sit to paint each day (the men prefer to stand, with tables supporting the canvases on their side of the art shed). Focusing on their brilliantly coloured paintings in a silent bubble of intense concentration, the women’s connection with country is so deeply felt that they mentally ‘inhabit’ it as they work. Country is always with them: it was clear when I visited a local Seven Sisters creation site that their imagery is often directly linked with the ochre paintings that adorn the cave walls there.

‘Seven sisters’

The women who painted these seven works span three generations. Tjampawa Katie Kawiny is the most senior, and is a traditional owner of Tjurma country. For Seven sisters 2011, she and her daughters painted an important creation story about the constellations of Pleiades (the sisters) and Orion (Nyiru, an evil man who wants to marry the eldest sister). The seven sisters travel between the sky and the earth to escape Nyiru’s unwanted attention, but he always finds them. In an attempt to catch them, Nyiru uses magic, turning himself into tempting kampurarpra (bush tomatoes) and the most beautiful Ili (fig) tree for them to sleep under. Aware of his magic, the sisters go hungry and run through the night to avoid being caught. Eventually they fly back into the sky, reforming as the constellation we see today.

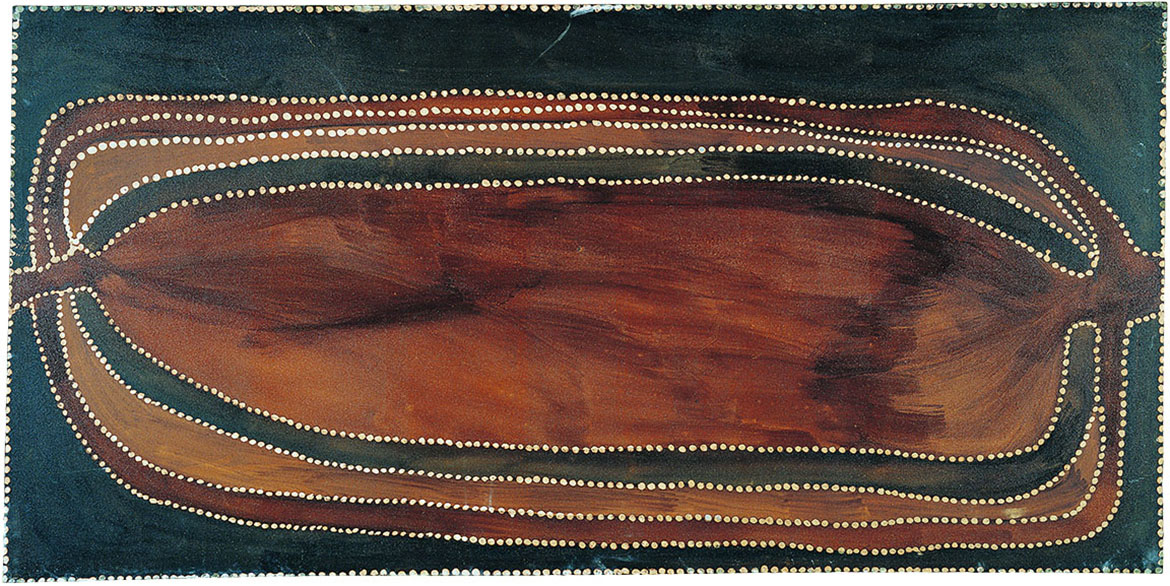

‘Mingkiri Tjukurpa (Mice Dreaming)’

Also very senior in Anangu law and culture is Wawiriya Burton, who is revered as a ngangkari (traditional healer). She started painting in 2008, but originally specialised in baskets and punu (wood) carvings. Her paintings depict Dreaming stories from her father’s country near Pipalyatjara, west of Amata, where she was born. With her daughters, she has painted Mingkiri Tjukurpa, a sacred story from Western Australia about the small female mice found in the desert. In Mingkiri Tjukurpa (Mice Dreaming) 2011, the mice are pregnant and, after giving birth to many babies, they must journey to the surrounding rock holes in search of food and water to feed their young. The dotted lines represent the mice tracks in the sand.

‘Ngayuku ngura (My country) Puli murpu (Mountain range)’

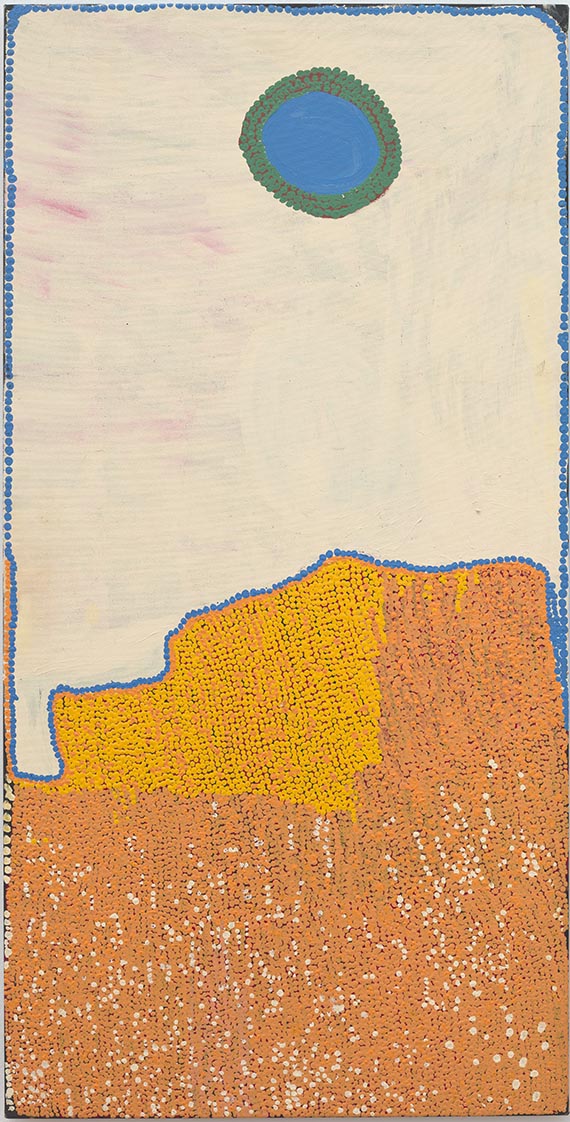

‘Puli murpu (Mountain range)’

Ruby Tjangawa Williamson, along with Wawiriya Burton, is a senior law woman committed to fostering traditional culture, storytelling, dancing and painting. Punu 2011 marks the first time these two important artists have collaborated. Williamson began painting in 2000 at Minymaku Arts (now Tjala Arts) and her distinctive works have received increasing attention. Here, they have depicted two trees — ultukumpu and kalingkalingpa — from the country where they were born, near the Irrunytju community in Western Australia. For Ngayuku ngura (My country) Puli murpu (Mountain range) 2012, Williamson, her daughter Nita and granddaughter Suzanne Armstrong have painted Puli murpu — their mountain country near Amata, where women engage in ceremonial business. The different colours and designs represent variations in the landscape. Puli murpu (meaning ‘mountain range’, ‘rise’ or ‘ridge’ in Pitjantjatjara language) is one of Williamson’s main subjects. She also paints ultukunpa (honey grevillea), sand goanna, bush foods and the bush cat. Puli murpu (Mountain range) 2011, also a collaborative effort by these three artists, depicts the Musgrave Ranges behind Amata where they live. The dark areas are the mountains seen from the side and above, the blue in the middle represents kapi tjukula (rock holes) where water collects after rain, and the frond-like elements at the edge of these are ultukunpa (grevillea juncifolia), a‘honey plant’ that grows six metres high.

‘Punu’

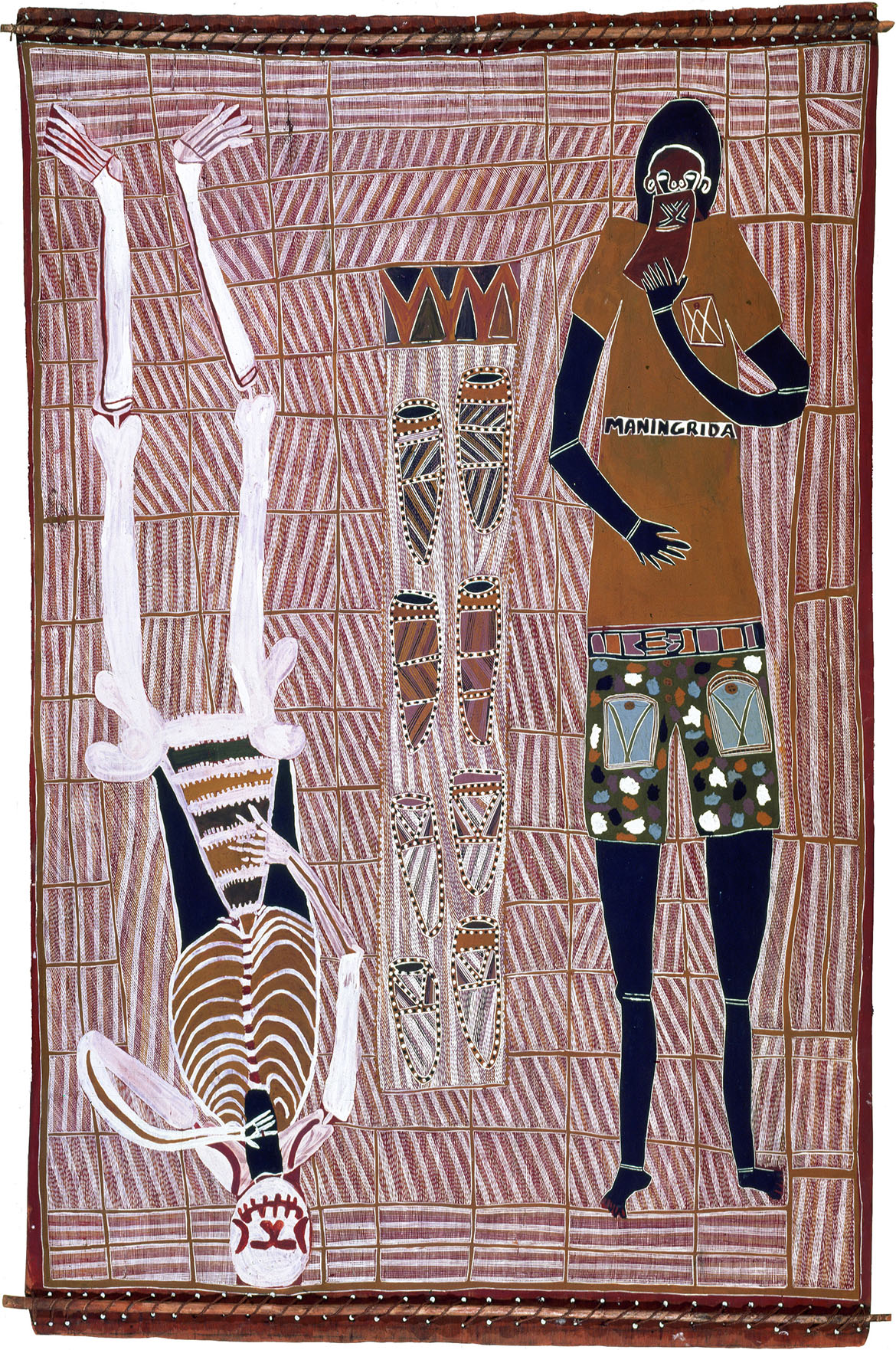

‘Waturru Nganampa Ngura (Waturru Our Country)’

From the Ken family of painters, sisters lluwanti Ken and Mary Katatjuku Pan have contributed Waturru Nganampa Ngura (Waturru – Our country) 2012, which depicts their country, Waturru, and some of the animals found there. Anangu women always respect the important lessons that animals impart — here, the animals teach them how to be good mothers: the birds and lizards show the women how to fight for their children, and how to protect and feed them.

And, finally, for Seven sisters and Tjala Tjukurpa (Honey Ant Dreaming) 2012, Paniny Mick and her daughters collaborated for the first time to depict two important stories: the Seven Sisters Dreaming and Tjala Tjukurpa, which tells of the ancestral honey ant whose tracks wind through the valley where Amata lies.

A unique aspect of this project has been the collaboration between senior artists, their daughters and granddaughters, which is very important to the Amata people. In all, 18 women were involved in making these paintings. Inspired by the commission to paint for ‘the special place’ (the Queensland Art Gallery), they have created works to be treasured for many years. The Gallery has forged a close bond with the Amata community that will endure for generations to come.

Diane Moon is former Curator, Indigenous Fibre Art, QAGOMA

‘Seven sisters and Tjala Tjukurpa (Honey Ant Dreaming)’

Acknowledgment of Country

The Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land upon which the Gallery stands in Brisbane. We pay respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander elders past and present and, in the spirit of reconciliation, acknowledge the immense creative contribution Indigenous people make to the art and culture of this country.

It is customary in many Indigenous communities not to mention the name of the deceased. All such mentions and photographs on the QAGOMA Blog are with permission, however, care and discretion should be exercised.

Featured image detail: Iluwanti Ungkutjuru Ken (Artist), Pitjantjatjarra people, Australia b.1944 / Mary Katatjuku Pan (Artist), Pitjantjatjarra people, Australia b.1944 / Sylvia Kanytjupai Ken (Collaborating artist), Pitjantjatjarra people, Australia b.1965 / Serena Ken (Collaborating artist), Pitjantjatjarra people, Australia b.1985 / Waturru Nganampa Ngura (Waturru Our Country) 2012

#QAGOMA