From the factory to the office, and from the studio to the streets, ‘Work, Work, Work’ brings together artworks from across the globe that respond to the ideas of labour. The concept of ‘work’ expands beyond the eight-hour working day as artists explore how we invest time and effort in education, the creation of artworks and the importance of social engagement.

A towering three-and-a-half-metre mosaic titled Work team contest 2009, by North Korean (DPRK) artists Kim Hung Il and Kang Yong Sam, depicts blue- and whitecollar workers celebrating their collective achievements. This is the artwork that greets visitors as they enter the GOMA exhibition ‘Work, Work, Work’. Moving through the exhibition, haunting photographs of decaying factories appear before us, along with stark images of gleaming glass, of steel office blocks and of slick shopping centres. What most obviously comes to mind when thinking about the theme of labour might well be images of workers and industry; however, ‘Work, Work, Work’ includes gems from the Collection that embody this idea in a more expansive way.

RELATED: The politics of persuasion: Work Team Contest

Works borne from laborious dedication feature throughout the exhibition — the stacks of hand-drawn newspapers by Mathew Jones, and Maria Taniguchi’s repetitious ‘brick’ painting, are just two examples. The hand of the artist is clearly visible in Jones’s About 1,000 copies of The New York Daily News on the day that became the Stonewall Riot copied by hand from microfilm records 1997. It took the artist ten months to laboriously hand-copy every word, photograph and advertisement that appeared in the Daily News on 27 June 1969, reproducing the newspaper’s industrial typeface in shaky and inconsistent handwriting, while the photographs are reduced to shading and hatching. In Taniguchi’s Untitled 2015, we can see gradations of blacks and dark grey on the surface of canvas; an effect she created by varying the amount of water and acrylic as she painted each small rectangle, painstakingly moving her way across the expanse of the canvas. Both Taniguchi and Jones, living in the digital era, emphasise their dedication to the handmade through the meticulous, gradual and labour-intensive process involved in creating these artworks.

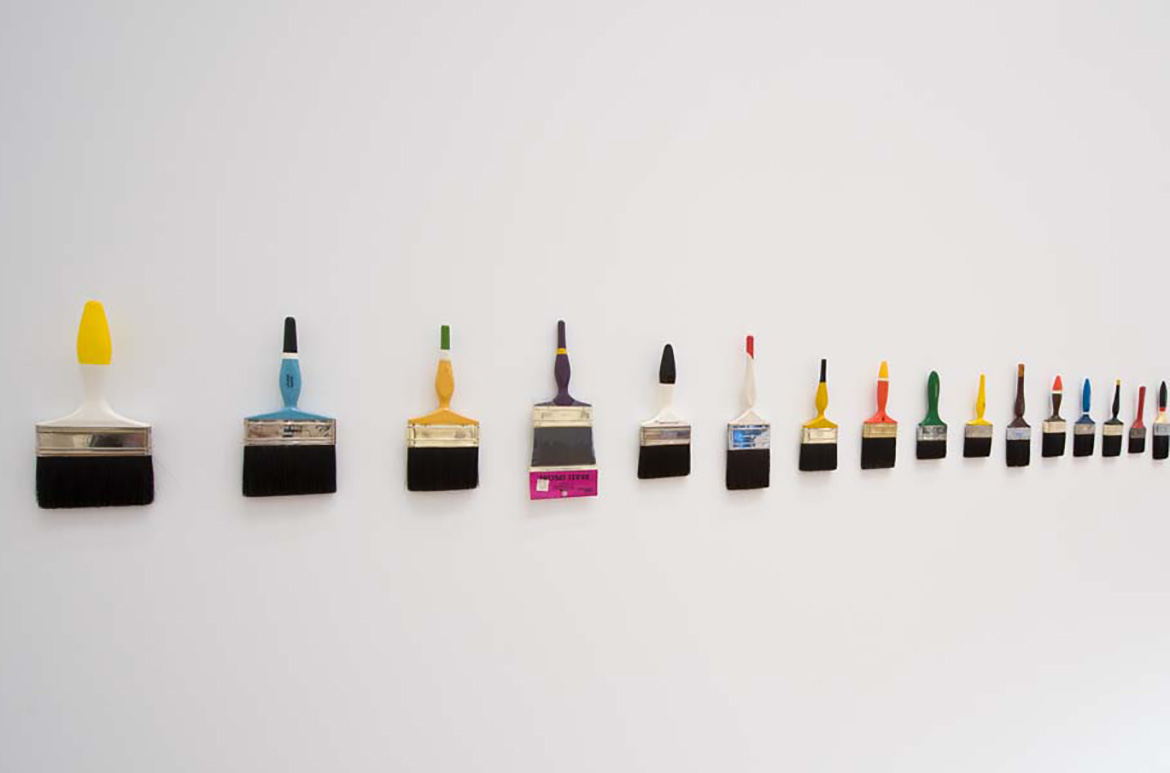

While replication highlights the hand of the artist in the aforementioned works, Robert MacPherson and Martin Creed deploy repetition using mass-manufactured products to downplay the technical skills of the artist and reflect on the often-overlooked devices on which artists rely to create their art. Working in the lineage of conceptual art, MacPherson collected 33 standard house-painting brushes and repeated the design and colour of their handles across 33 canvases, which are then presented alongside the original objects in Scale from the tool colour group 1977–78. In Creed’s Work no. 189 1995, 39 identical metronomes sit in a line along the floor, calibrated incrementally across the full spectrum of tempo speeds (from fast, presto, to very slow, lento). Set off all together, the metronomes — whose sole function is to keep time for practising musicians — produce a cacophony that seems, ironically, to lack musicality. The ‘tools’ used to create artworks are rarely on display in a gallery space, but here, they become the works under aesthetic scrutiny.

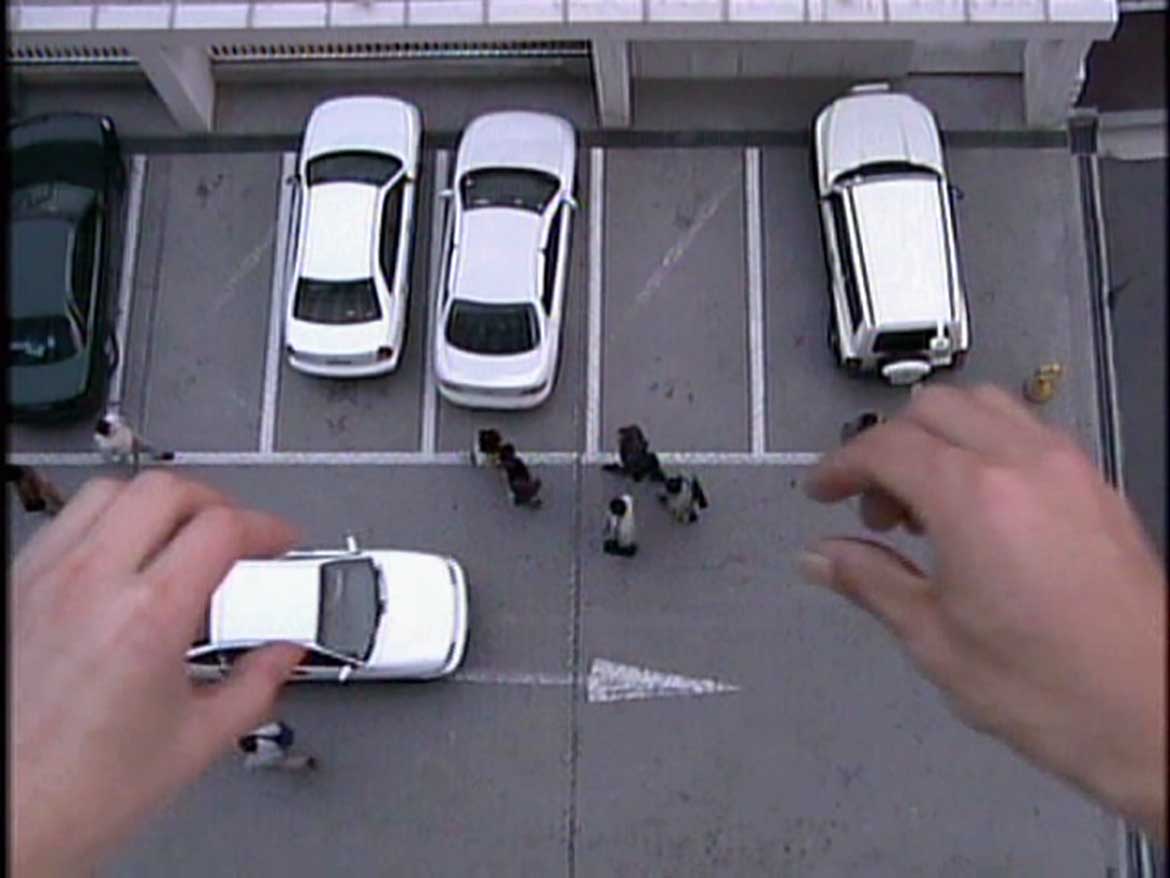

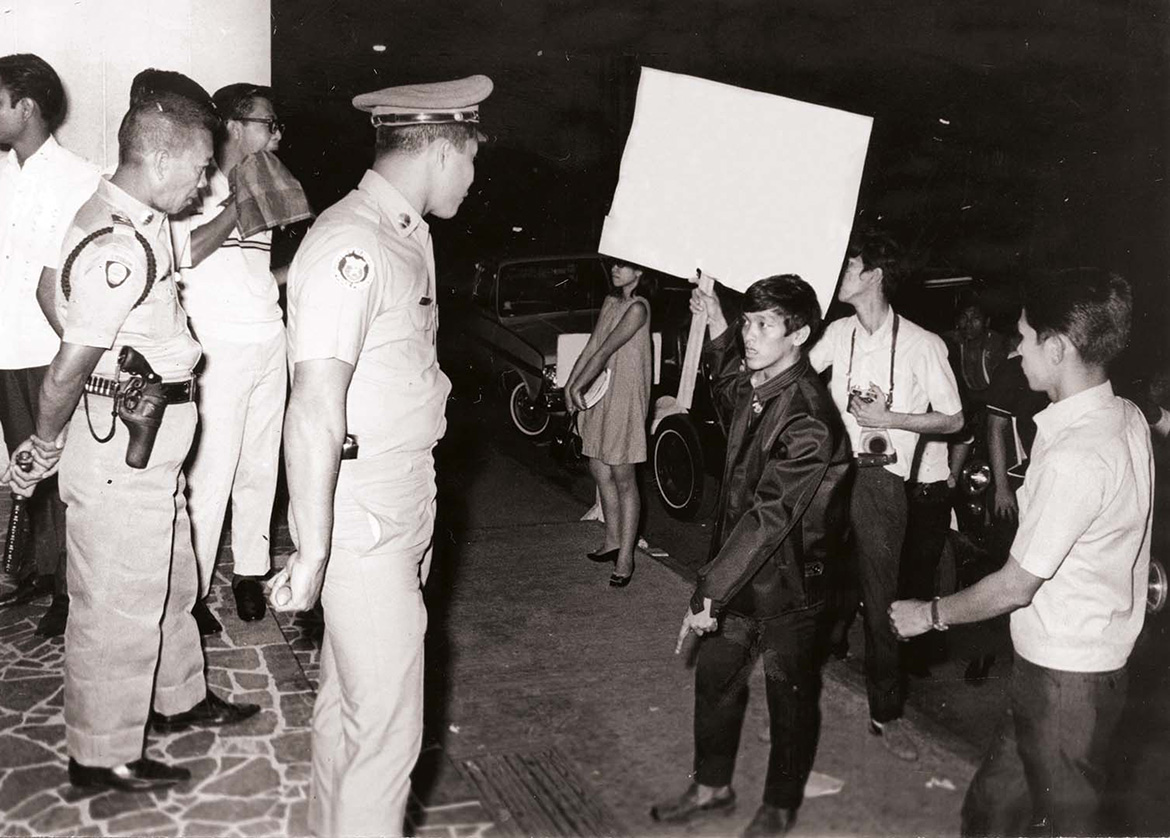

Part of the success of MacPherson’s and Creed’s artworks is their use of an accumulation of forms to create artistic weight. In works by Kiri Dalena, and by Gabriella Mangano and Silvana Mangano, people are united to become politically persuasive. Dalena’s Erased slogans works of 2012–15 appropriate archival newspaper photographs of protestors in the Philippines. The digital erasure of the messages on the placards more tightly focuses our attention on the body language of the protesters. In Gabriella Mangano and Silvana Mangano’s video There is no there 2015, performers collectively re-enact gestures the artists have gathered from news images, and from observations of the broader Australian social climate. The accumulation of people and the repetition of their movements in these works remind us of not only our shared corporeal reactions, but also of the choreographed nature of political events.

RELATED: Gabriella Mangano and Silvana Mangano: There is no there

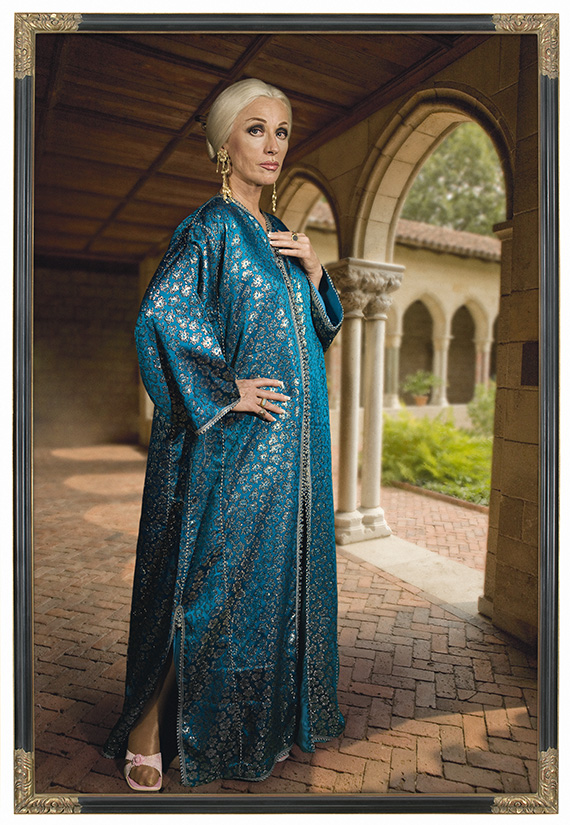

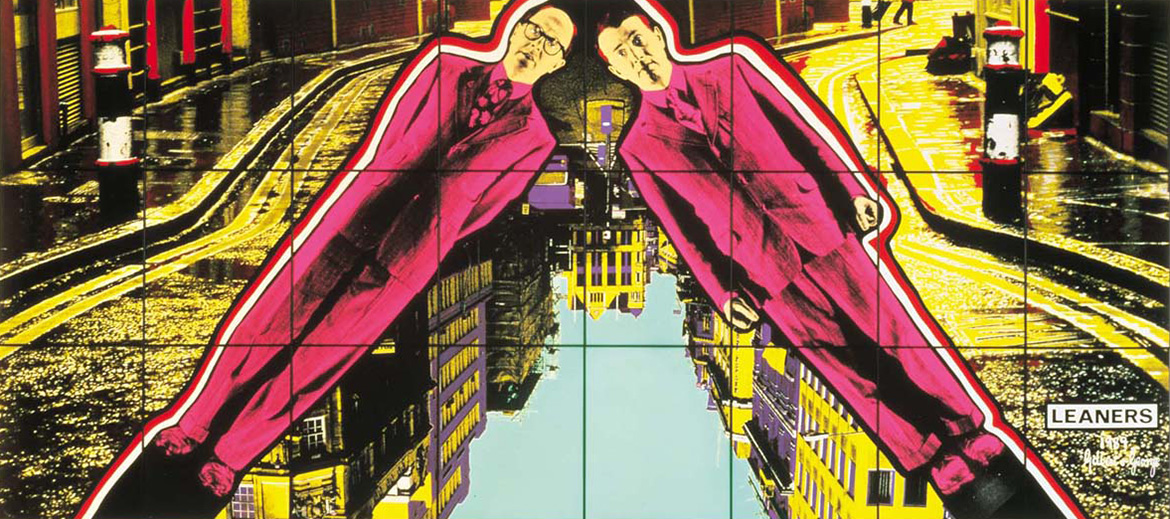

English duo Gilbert & George have worked collaboratively for over 50 years. Leaners 1989 is a strong image of how individuals within collectives can and must rely on each other. This monumental acid yellow-andpink multi-panel photograph has the artists sharply angled towards the centre of the work with their heads almost resting together, giving the appearance that if one should move away, the other might fall. This sense of entangled collaboration is also present in Warlpiri artists Jimija Jungarrayi Spencer and Paddy Jupurrurla Nelson’s striking painting Wakulyarri Jukurrpa (Rock Wallaby Dreaming) 1987. Not only does the artwork capture the shared cultural knowledge of these two important painters, but also it demonstrates their painterly finesse, creating a work that is full of tension, in which form and colour push and pulse against one another. Despite arising from different formal approaches, both Leaners and Wakulyarri Jukurrpa express a commitment to collaboration.

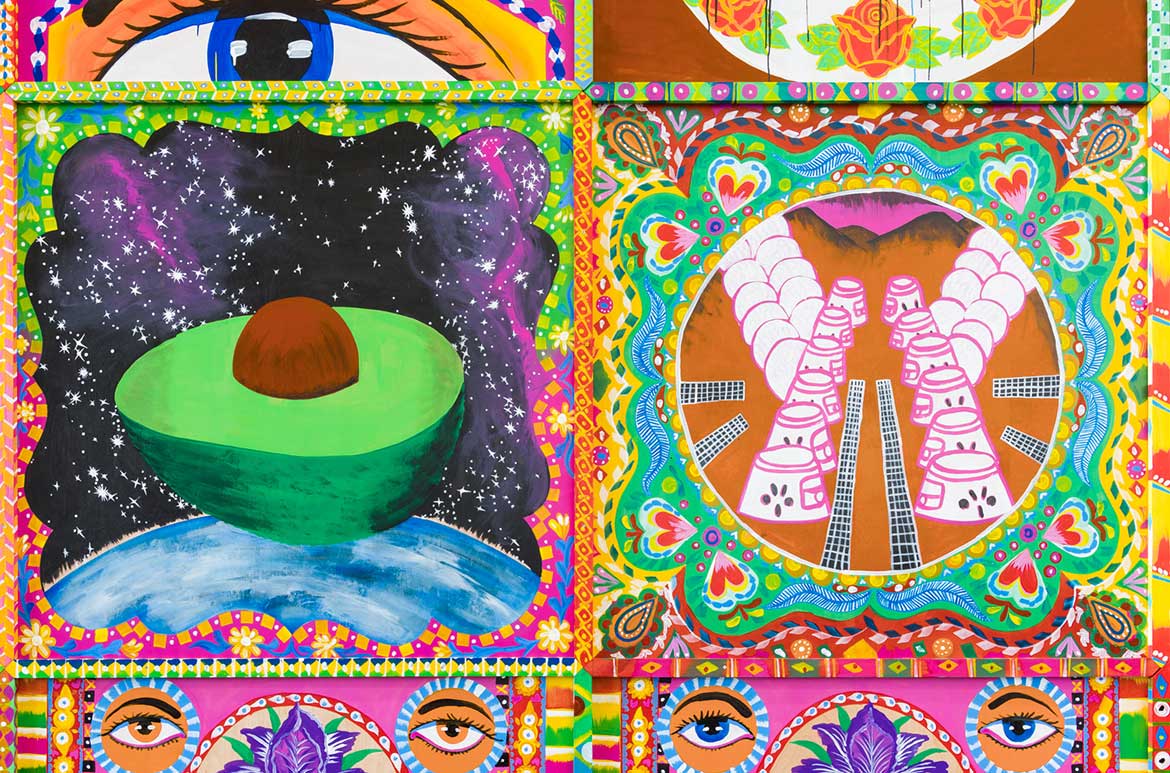

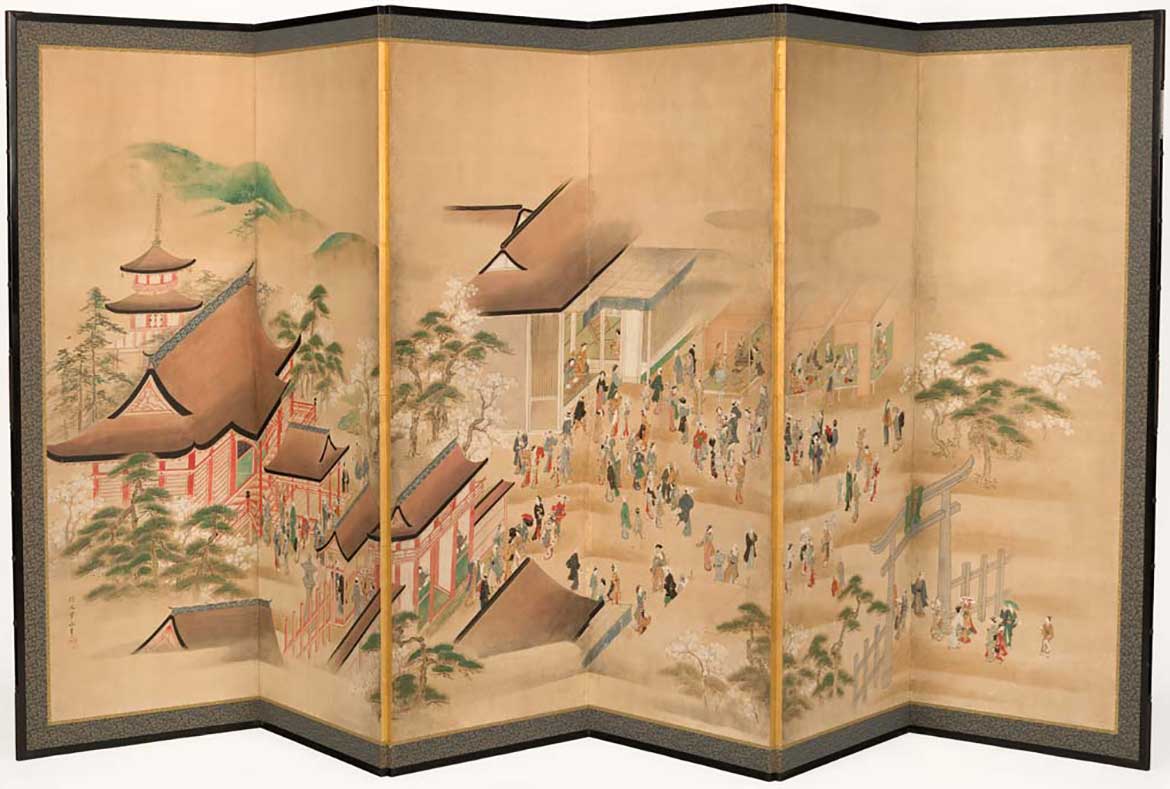

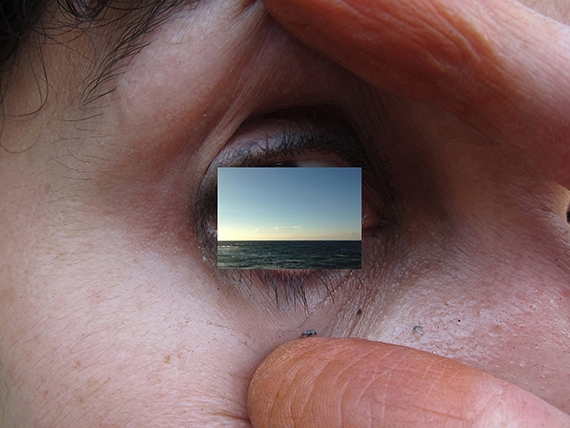

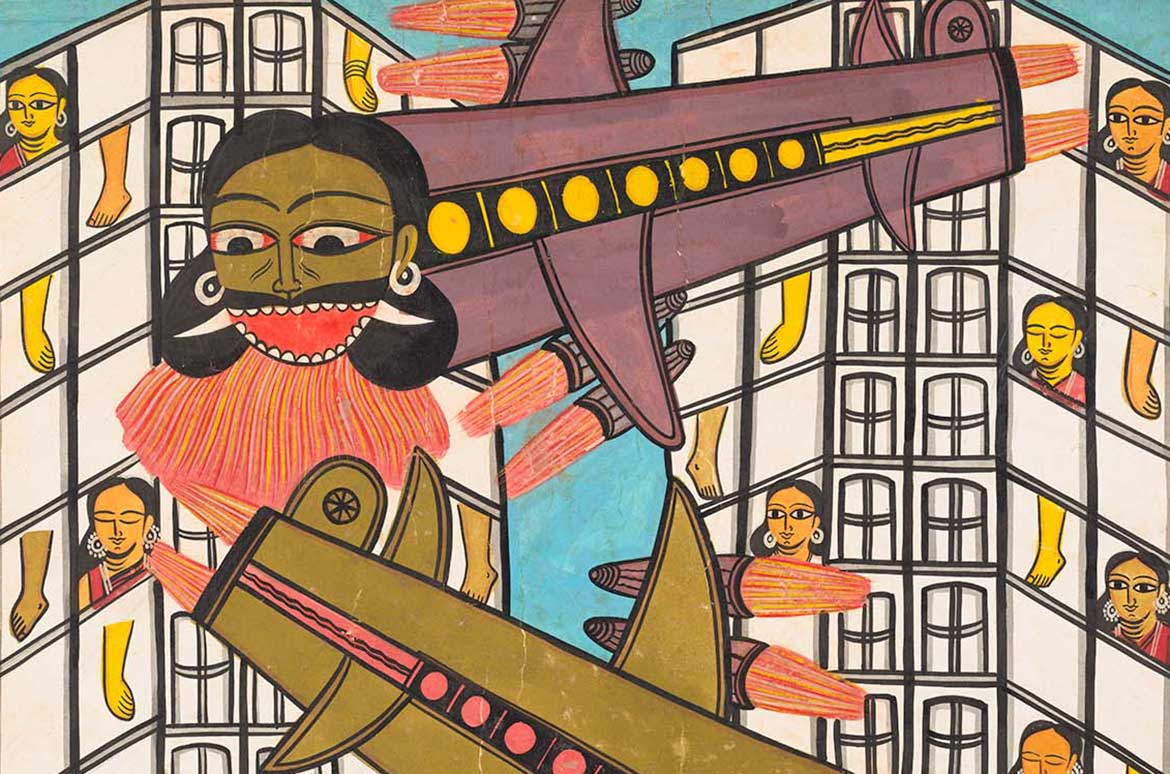

The desire to share artistic expression and knowledge unites Kota Ezawa’s three-channel video and the proto-cinematic paintings of the patua (artists) of West Bengal. The patua would historically travel from one village to another, slowly unrolling the patachitra (painted cloth scrolls) to reveal stories in sequential frames, and singing the tales depicted. More recently, the makers of patachitra have incorporated local and global events in their works, highlighting the shared narratives of ancient mythology and contemporary geopolitics. In Ezawa’s Lennon Sontag Beuys 2004, cartoon renditions of musician John Lennon (1940–80), writer Susan Sontag (1933 2004) and artist Joseph Beuys (1921–86) argue for the power of art to effect social change. The three subjects speak simultaneously, competing to be heard, and the audience must actively listen to understand what is being said by each — a salient reminder in the current ‘noisy’ political climate.

RELATED: Jaba Chitrakar, traditions of West Bengal

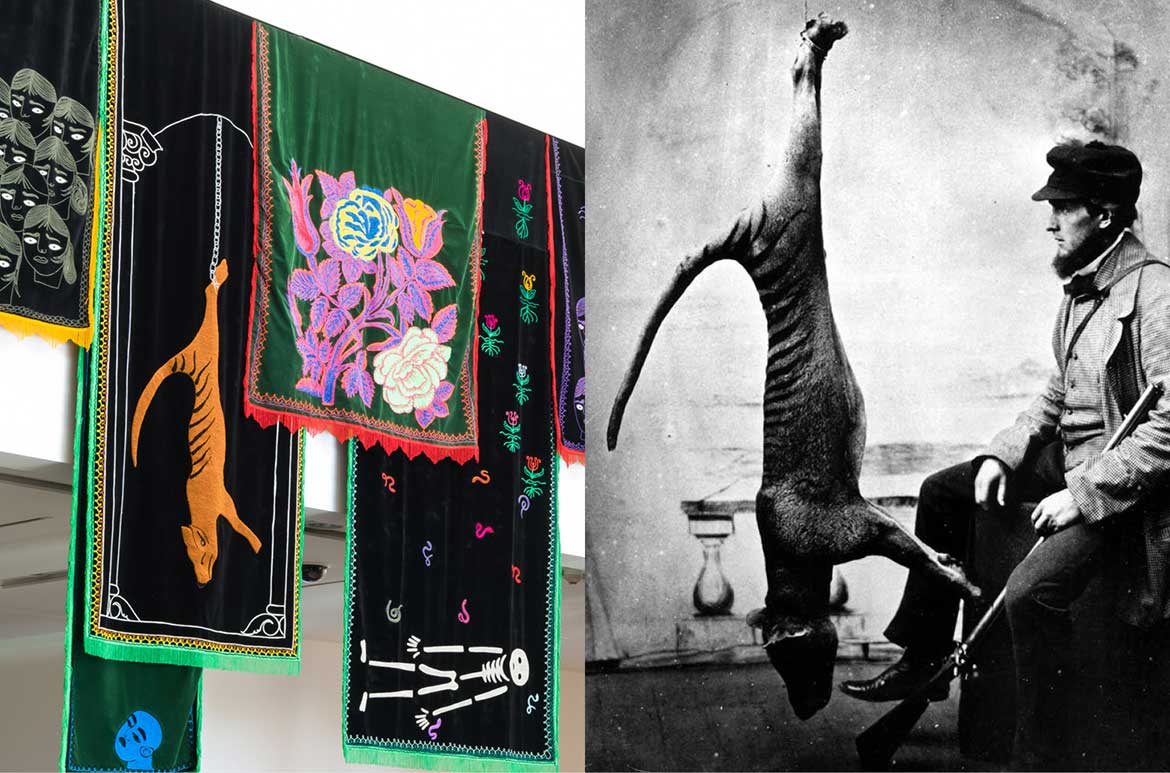

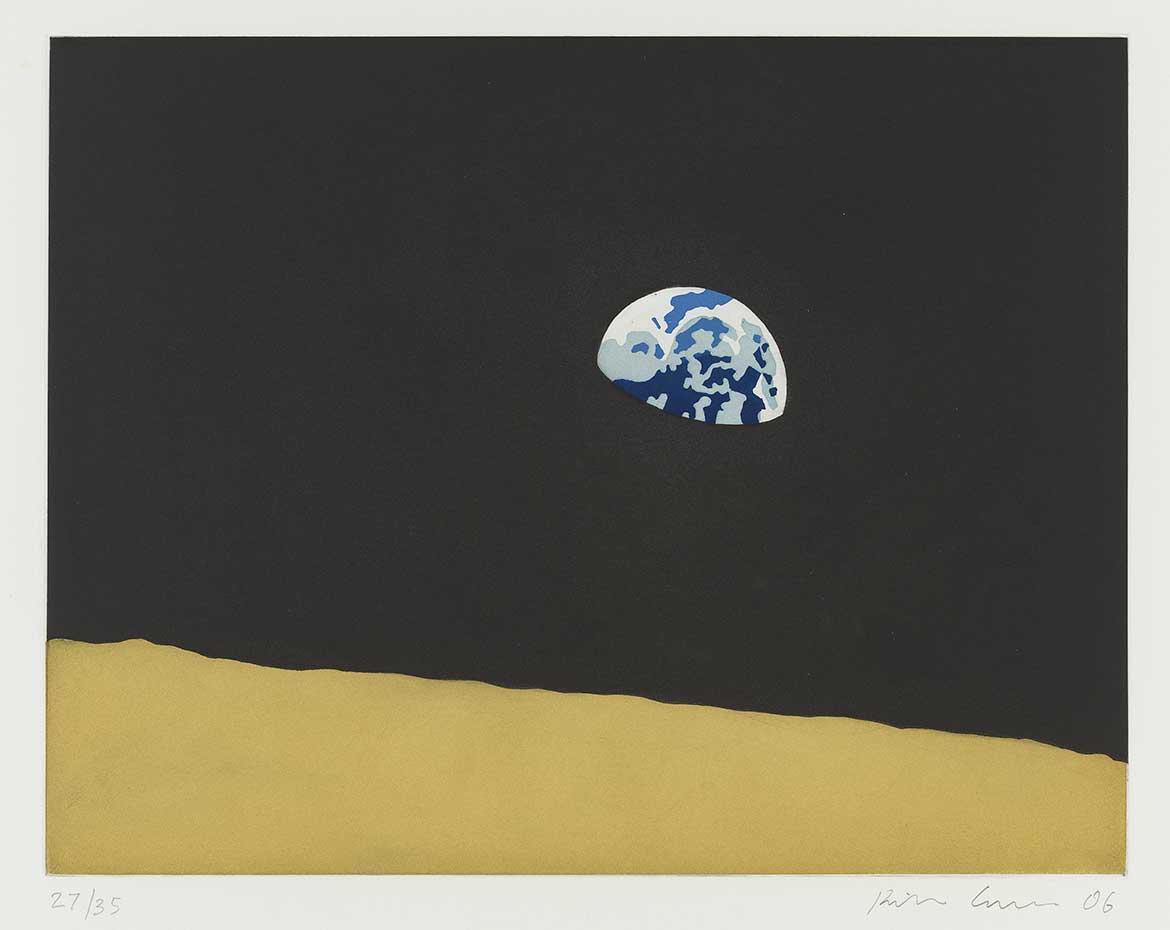

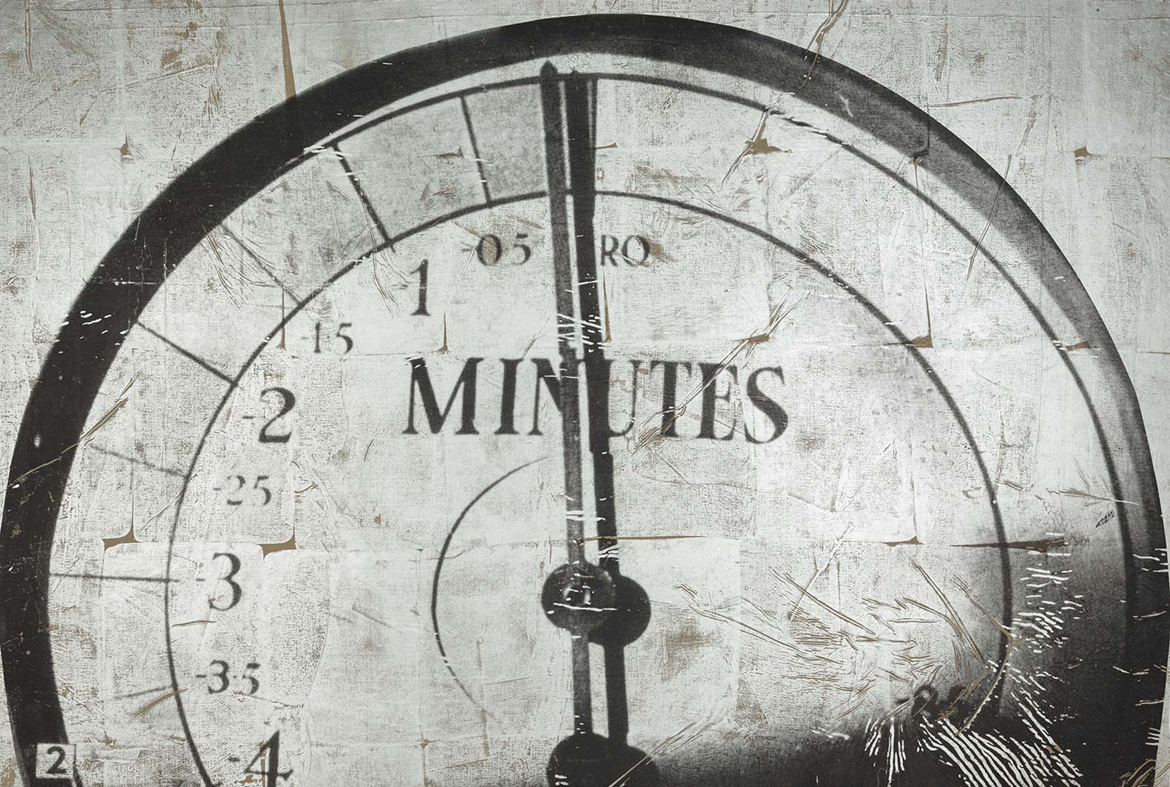

RELATED: Brook Andrew: TIME 2012

The news cycle repeats pictures of environmental and social degradation. Brook Andrew’s nuclear clock, in TIME I 2012, with its hands ticking down the half-minutes to zero hour, reminds us that life as we know it may end. Yet, by emphatically dedicating themselves to communicating with others, artists continue to affirm life, leaving the rest of us with the decision to either watch the clock or start collaborating on a more promising future.

Ellie Buttrose is Associate Curator, International Art, QAGOMA.

Know Brisbane through the QAGOMA Collection / Delve into our Queensland Stories / Read more about Australian Art / Subscribe to QAGOMA YouTube to go behind-the-scenes

‘Work, Work, Work’ featured creative output across media: some artists use photography and video to document people at their day jobs and to study the architecture of our working environments; while others create sculptures and installations from industrial materials and the motifs of bureaucracy. Regardless of the medium employed, these artists reflect the influences of the workplace on society, and those of society on the workplace.

Featured image: Installation view of ‘Work, Work, Work’, featuring Gabriella Mangano and Silvana Mangano’s There is no there 2015, Kim Hung Il and Kang Yong Sam’s Work team contest 2009, and Mathew Jones’s About 1,000 copies of The New York Daily News… 1997 / Photograph: Natasha Harth

#QAGOMA