Emily Wakeling continues her conversation with Kim Barrett, Conservator, Works on Paper with a focus on displaying and caring for Japanese Scrolls. The exhibition ‘A fleeting bloom’ at the Queensland Art Gallery includes a number of hanging scrolls, and we prepared these delicate works for display.

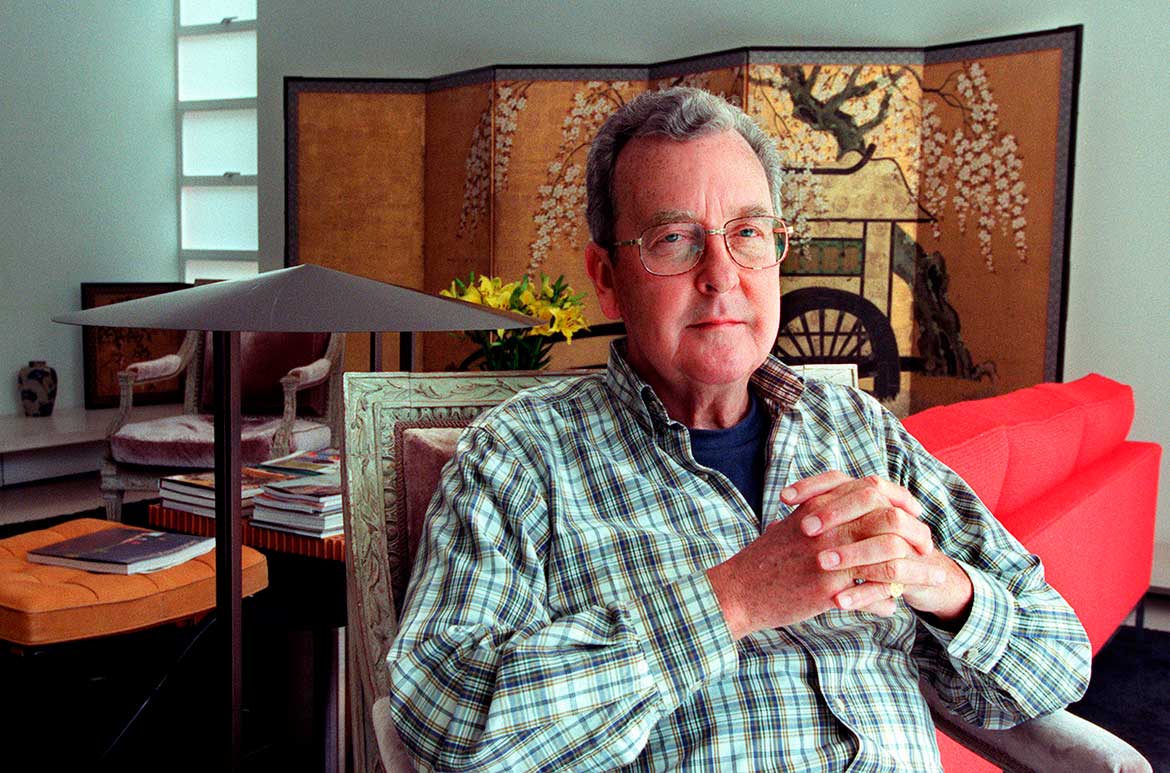

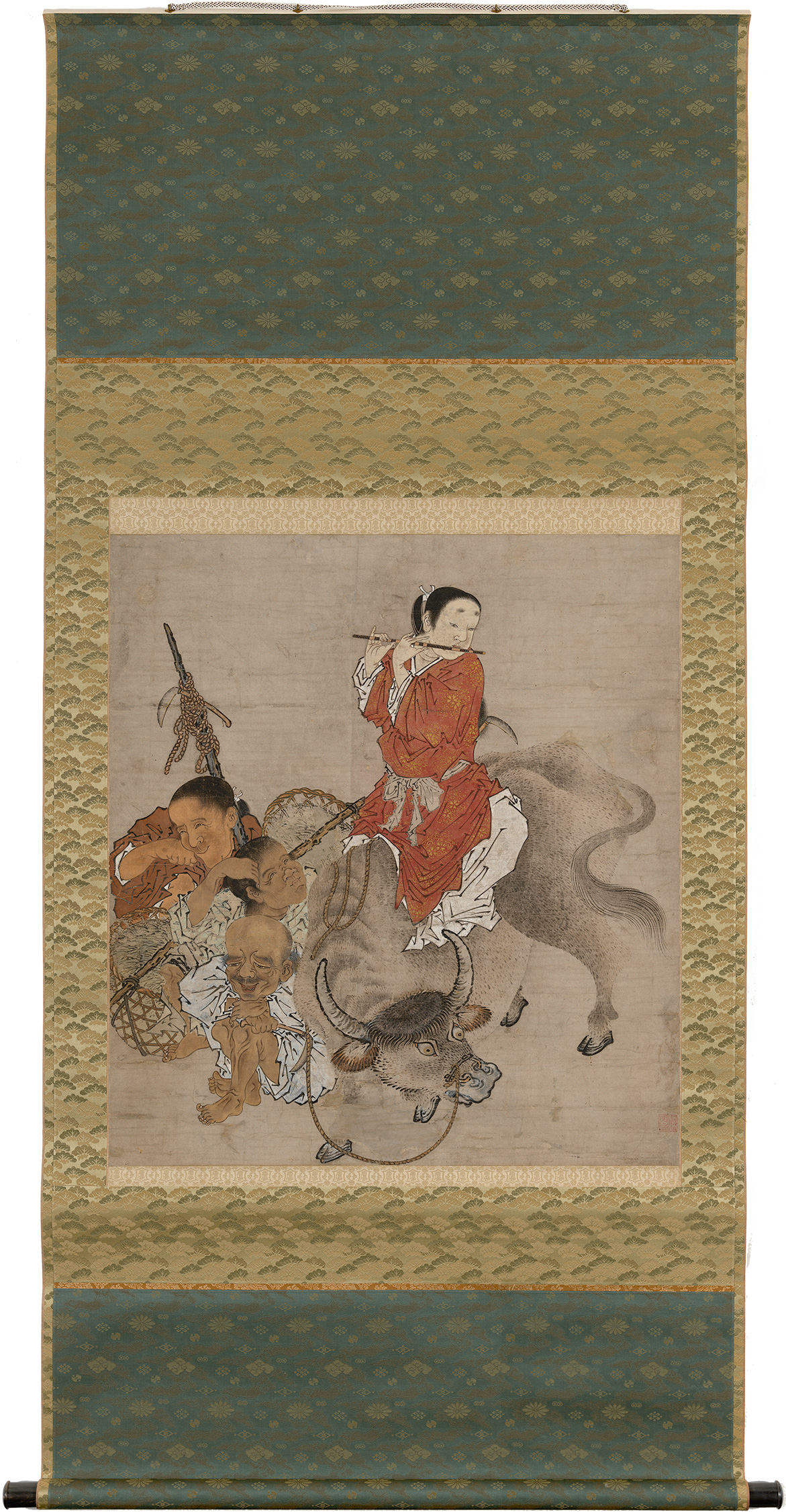

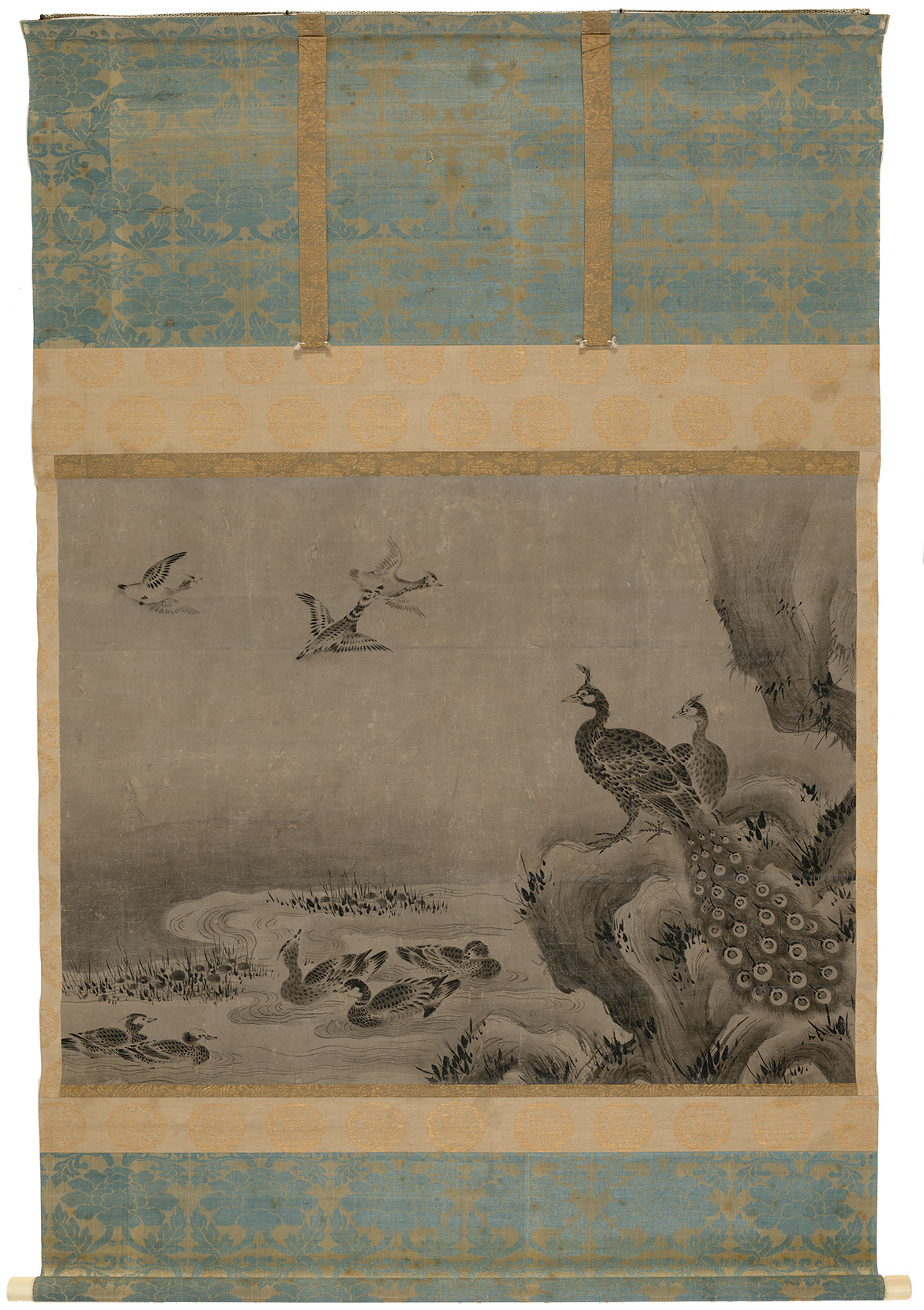

Japanese scrolls are long works on paper that are rolled up when stored or carried. There are essentially two types of scroll: emakimono (hand scroll) and kakemono (hanging scroll). While emakimono are made to be viewed horizontally and slowly opened and closed to reveal a sequence of pictures, the kakemono are displayed fully open, hanging vertically on a wall. The James Fairfax AC Bequest includes hanging scrolls from the Edo period (16th–18th century), which Fairfax primarily collected during trips to Kyoto and Tokyo in the early 1990s. Some are strictly ink on paper, but others incorporate pigments or have been painted on silk.

Hanging scroll: Peacocks and other birds

Preparing the scrolls for display

As I mentioned in my previous blog post on folding screens, one of the conservator’s first tasks when preparing works for display is to undertake a condition assessment. Japanese scrolls such as these have a long tradition of being remounted — backing paper and silk brocade borders are often replaced when they wear out.

‘Part of the assessment we undertake on scrolls is determining if the mount is original or if it has been sympathetically remounted at some point in the past,’ Barrett says. ‘We examine the entire scroll for signs of wear and tear and to determine if it is stable for display. Opening and closing a rolled painting, which is essentially what a scroll is, adds to its wear and tear. Incorrect tensioning when rolling and unrolling a scroll can cause and exacerbate creasing and eventually lead to cracking.’

Scrolls generally have three paper layers, adhered with wheat starch. Over time this adhesive becomes stiff and brittle, and this is often when you see creases or cracks appearing, exacerbated by rolling and unrolling. Careful handling and good storage practices can alleviate these problems.

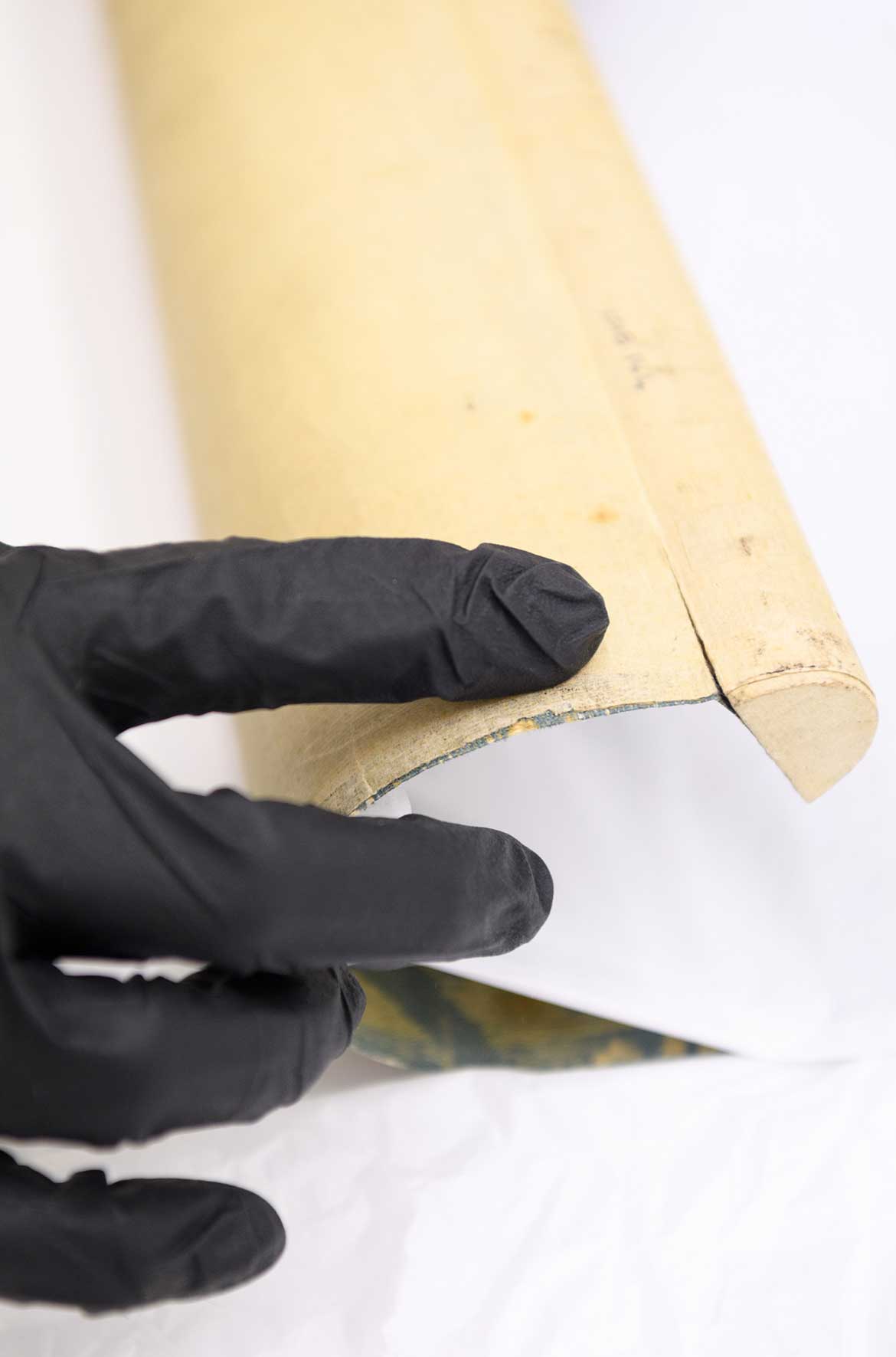

When I asked if it would be better for the scrolls to be stored flat, Barrett explained that this method would cause problems too, posing additional risks to the work. She also identified some slight tearing where the paper joins the top rod.

‘This is one of the weakest areas of the scroll,’ says Barrett while indicating the damage. ‘This type of problem can be avoided by good handling practices. I will treat this scroll by stabilising the join.’ To do this, she’ll make a small non-intrusive reinforcement to the back of the scroll using the traditional materials of kōzo paper and wheat starch paste.

‘Sometimes similar repairs are made on the back of the scroll to areas of creasing. If this is done at an appropriate time, this type of repair can slow down the development of the crease and extend the life of the mount. Properly cared for, a scroll mount may last a century or more. But if damage to the mount becomes too severe, the painting itself may be at risk and a new mount may be needed. To decide, always consult a qualified conservator who is an expert in scroll mounts.’

Caring for the scrolls

To avoid stress on the paper, Barrett recommends rolling and tying the scrolls in the traditional way, leaving no slack in the rolled scroll. She also mentions the use of futomaki, a cylindrical insert that expands the size of the rod for storage. This minimises the stress in rolling and unrolling and can help support the scroll. Futomaki are traditionally used for scrolls on heavier paper or with thicker pigments, and when used appropriately they can help extend the life of a mount.

‘When we were discussing folding screens, we talked about the important process of consolidation to save the paint layer from flaking off. This hasn’t been an issue with the scrolls in the Collection, as the paint layer is generally much thinner owing to the scroll’s ability to be rolled up.’

I ask if the type of paper differs between the scrolls and screens.

‘The paper itself would be similar to that found in folding screens, with slightly thicker sheets used for the backing layers. The final backing layer, made of kōzo fibre, is quite thick and contains china clay.’

Installing the scrolls for exhibition

‘When hanging a scroll, first ensure that it is in a stable condition,’ Barrett says. ‘The hanging cord, the metal eyelets attached to the hanging stave and the knobs on the bottom rod should all be secure. If the scroll has been unrolled for examination, it must be rolled up again before hanging. The height and width of the wall you intend to hang on will need to be larger than the scroll itself.’

Barrett has laid the scrolls out flat in the QAGOMA Collection Study Room, and she continues to talk through the installation process while pointing to the hanging system.

‘Have a suitable secure hook fixed to the wall to hang from. Undo the tying cord and slide it out of the way, generally to the right. It will hang behind the scroll on the wall. If there are hanging strips, as there generally are with Japanese scrolls, unroll on a flat surface to expose these and unfold, unrolling just enough for them to lie as they should when the scroll is hung. The scroll can then be hung by cradling the rolled scroll in one hand and the centre of the hanging cord in the other. Once the hanging cord is securely hooked onto the wall cradle, hold the rolled scroll with both hands and then carefully and slowly unroll the scroll down the wall. Steady the lower rod before releasing the scroll, and then straighten it by adjusting the cord. ’ Barrett explains that it can help to have another person hold the top rod, as some scrolls will have a natural tendency to roll back up again. QAGOMA conservators sometimes use small leather book weights (weights containing lead shot inside a soft leather case) to gently hold down the scroll at the ends when examining them.

In museum standards, the scrolls are classified as ‘sensitive’, and this categorisation determines the recommended maximum length of time that the works should be displayed.

‘Sensitive works are recommended for shorter display periods of up to six months, and then rested in storage for a minimum of two years before considered suitable for display again. This helps to reduce the light exposure to the works and will minimise fading. This will help make sure the Gallery can give the works a long life as well as sharing them with audiences many years into the future.’

Emily Wakeling is former Assistant Curator, Asian and Pacific Art, QAGOMA

Hanging scroll: Young man playing a flute on an ox accompanied by three figures

Hanging scroll: Peacocks and other birds

Featured image: Unrolling Hanging scroll: Young man playing a flute on an ox accompanied by three figures 17-18th century for examination.

#QAGOMA