Fairy tales are not bound by borders, social class, custom, religion, age or time. They are products of our desire to consider the world around us from within the safe realm of fiction. Fairy tales come to meet us where we are; they shift and change to reflect the needs and wants of audiences. The hopefulness embodied in many fairy tales once functioned to alleviate the drudgery of daily life — they both entertained and imparted wisdom.

The classic tales of ‘Cinderella’ and ‘Snow White’ promised better times and, if this was not possible, at least concluded with satisfactorily gruesome endings for the wicked. These stories were written at a time when women’s autonomy and access to education were severely restricted and, according to the law, they were subordinate to their fathers or husbands. For early readers, ‘happily ever after’ represented the institution of marriage and a life of stability, free of strife and hardship.

Watch | Director Tarsem Singh’s filmic adaptation of ‘Snow White’

Courtesy: Relativity Media

Watch | Go behind-the-scences of Eiko Ishioka’s costumes

Courtesy: Relativity Media

When the Parisian aristocracy recorded these stories — with their ostentatious ballrooms and banquets, luxurious carriages, opulent dresses, expensive jewellery and impossible shoes — they evoked aspirational wealth, status and power. Marrying for love, and between classes, were risky topics for the time.

While the visions of adventure, community, happiness and love in wonder tales of centuries past still intrigue contemporary audiences, many stories today are being retold in ways that challenge patriarchal systems and imagine new, more equitable ways of living for all.

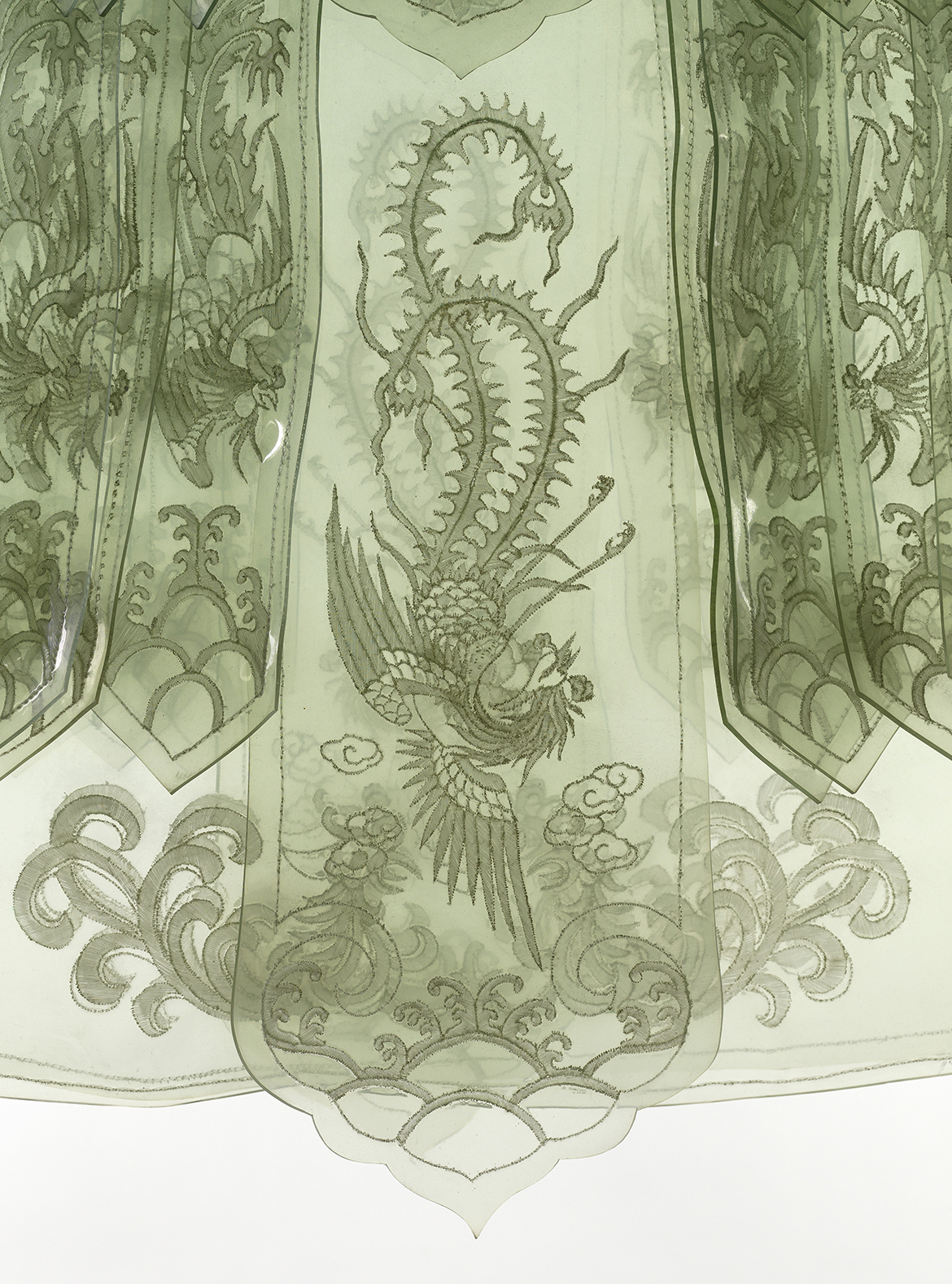

A romantic fairy tale requires a wardrobe to match. Dress is critical to the identity of many fairy tale characters: it indicates status or occupation, and signals magical transformation. For Japanese designer Eiko Ishioka the costumes for the queen in Mirror Mirror (2012) are a demonstration of power and wealth. The costumes worn by Julia Roberts as ‘Queen Clementianna’ are oversized and highly embellished, sculptural in form and bold in design and colour. For Ishioka, it was important to reveal aspects of the character’s personality and emotions, the gold thread and detailed embellishment is important and reflects Clementianna’s assertions in the film that gold is her colour. The eye-catching ‘Peach dress’ costume (illustrated) is intended to intimidate her subjects through its opulence and scale. Another stunning creation for Queen Clementianna, the ‘Green dress’ costume (illustrated) conveys the complexities of character through colour, which shows the depth of the queen’s envy of Princess Snow played by Lily Collins, the highly constructed and precise nature of the dress also reflects Clementianna’s attempts to conceal her true personality in order to woo the prince played by Armie Hammer.

Eiko Ishioka (designer) ‘Green dress’ and ‘Peach dress’ costumes

Eiko Ishioka (Designer) ‘Yellow dress with hood’ costume

Showcased in the ‘Fairy Tales’ exhibition are eight incredible creations by Ishioka, created for Mirror Mirror — director Tarsem Singh’s filmic adaptation of ‘Snow White’. Richly detailed and sumptuously executed, Ishioka’s costumes bring the impossible luxury of fairy tales to life and highlight the aspirational nature of stories in which characters rise above servitude to a life of privilege and financial security.

Buy Tickets to ‘Fairy Tales’

Until 28 April 2024

Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane

‘Fairy Tales’ unfolds across three themed chapters. ‘Into the Woods’ explores the conventions and characters of traditional fairy tales alongside their contemporary retellings. ‘Through the Looking Glass’ presents newer tales of parallel worlds that are filled with unexpected ideas and paths. ‘Ever After’ brings together classic and current tales to celebrate aspirations, challenge convention and forge new directions.

Travel with us in our weekly series through each room and theme of the ‘Fairy Tales’ exhibition at Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) as we focus on the stunning costumes from Mirror Mirror (2012) on display in Australia for the first time.

DELVE DEEPER: Journey through the ‘Fairy Tales’ exhibition with our weekly series

EXHIBITION THEME: 13 Ever After

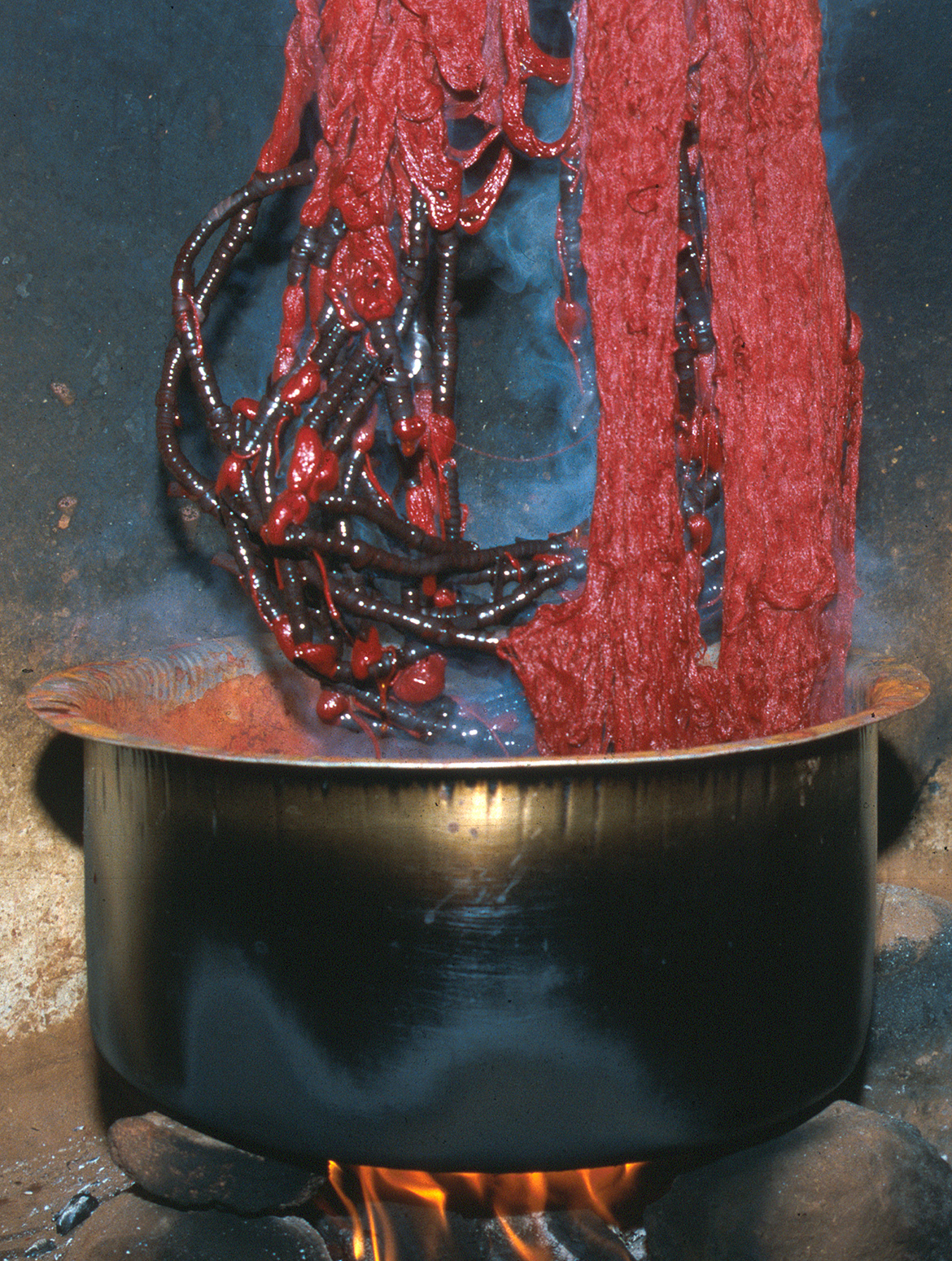

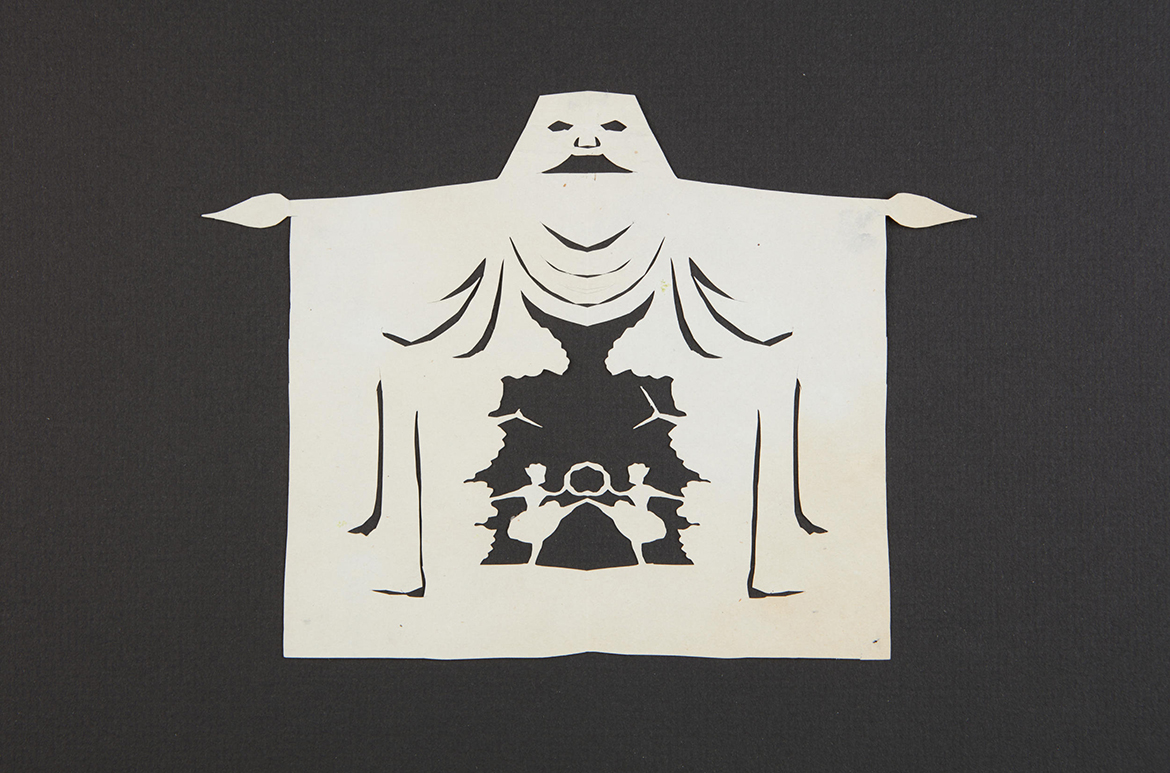

Ishioka described her concept for Mirror Mirror as ‘hybrid classic’, an approach that allowed the designer to draw on fashions from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries to create the grandeur and whimsy of the fairy tale aesthetic sought by director Tarsem Singh. Ishioka led the creation of more than 400 costumes, as well as the purchase of and alterations to an additional 600 existing costumes. While many were completed by local costumiers and craftsman in Montreal, close to her studio and the film’s shooting location, the primary costumes were handmade in New York across four different ateliers; Tricorne Costumes, Jennifer Love Costumes, Carelli Costumes and Eric Winterling Costumes.

Eiko Ishioka (designer) ‘Cream wedding dress’ costume

The centrepiece of these extraordinary creations on display in ‘Fairy Tales’ is the exceptionally romantic ‘Cream wedding dress’ costume for Snow’s stepmother, Queen Clementianna. With its heavy layers of silken petals and vine motif, the garment has a vast circumference of 8.5 metres, weighs approximately 27 kilograms, and was designed to dominate the room.

Eiko Ishioka (designer) ‘Swan dress’ & ‘Rabbit suit’ costumes

These are the first of two costumes created for Princess Snow (Snow White) and her handsome beau, Prince Alcott. Worn during the film’s masquerade ball scene, the princess’s ‘Swan dress’ costume symbolises her youthful vitality and gentleness. The flowing white gown, with its wings and headdress, depicts Snow’s desire to escape the restrictive confines of life with her stepmother, Queen Clementianna.

Accompanying this costume is the ‘Rabbit suit’ costume worn by Prince Alcott, chosen for him by the queen, who is trying to charm the prince into marriage. She attempts to flatter him by saying, ‘In folklore, the rabbit is known to use cunning and trickery to outwit his enemies’. With its prominent bunny ears and lopsided top hat, Prince Alcott concedes that he ‘looks ridiculous’ when dancing with Princess Snow.

Eiko Ishioka (designer) ‘Wedding dress’ & ‘Wedding suit’ costumes

Princess Snow’s blue wedding gown features a burst of orange sleeves and an oversized bow at the back, complementing Prince Alcott’s tasselled wedding attire. Both costumes signify a new, independent future, free of the clutches of the soon-to-be-dead Queen Clementianna. In the film, the princess is wearing this gown as she begins her new life with a Bollywood-inspired dance — a nod to the contemporary, fractured nature of the tale and the cultural heritage of the director.

The ‘Fairy Tales’ exhibition is at Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA), Australia from 2 December 2023 until 28 April 2024.

‘Fairy Tales Cinema: Truth, Power and Enchantment‘ presented in conjunction with GOMA’s blockbuster summer exhibition screens at the Australian Cinémathèque, GOMA from 2 December 2023 until 28 April 2024.

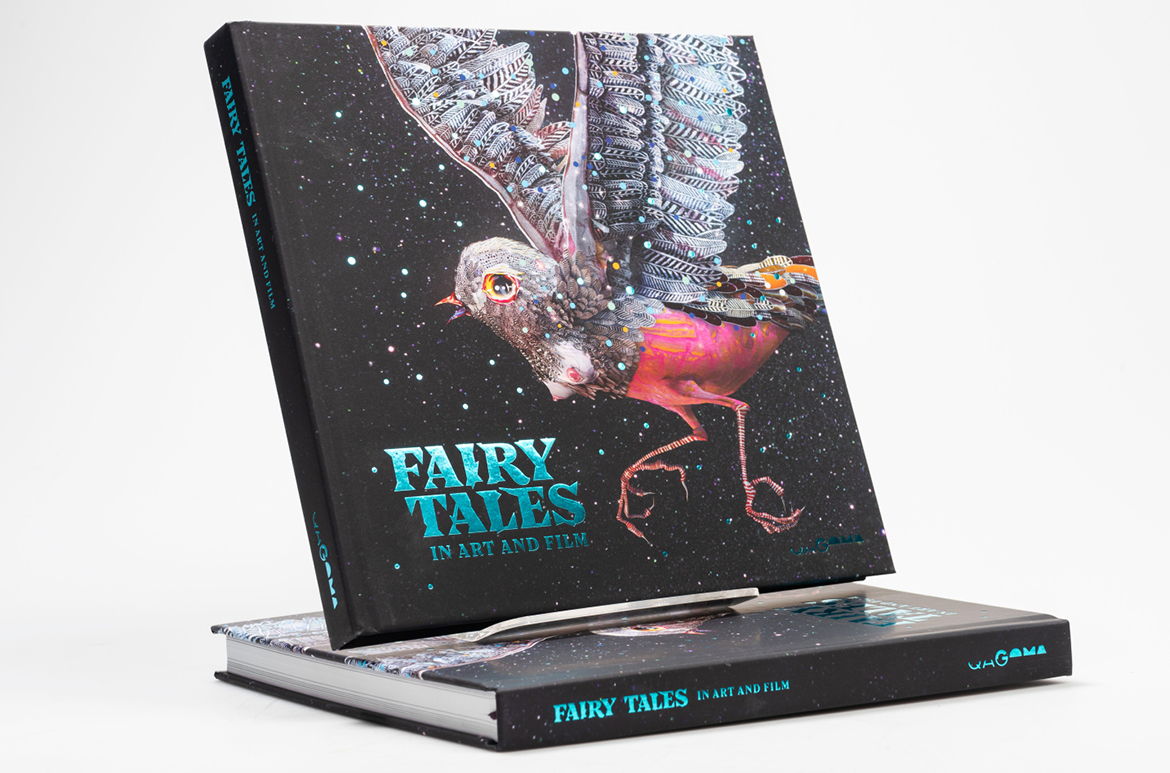

The major publication ‘Fairy Tales in Art and Film’ available at the QAGOMA Store and online explores how fairy tales have held our fascination for centuries through art and culture.

From gift ideas, treats just for you or the exhibition publication, visit the ‘Fairy Tales’ exhibition shop at GOMA or online.

#QAGOMA