QAGOMA’s Installation team are one of the Gallery’s many groups travelling under the radar, away from public attention, but whose crucial and careful work is on full view for the public. Installation is at the pointy end of a trajectory that involves many people pulling in unison to produce the exhibitions we see. We go behind-the-scenes during the installation of European Masterpieces from the Metropolitan Museum of New York.

LIST OF WORKS: Discover the artworks in ‘European Masterpieces’

DELVE DEEPER: Read more about the exhibition

THE STUDIO: Artworks come to life

WATCH: The Met Curators highlight their favourite works

How many people does it take to hang a Vermeer or Velázquez? A few, but not too many, and despite being quite a sophisticated process, conducted behind the scenes, the result can look so effortless that some may think they could have done the work themselves. But moving and installing works of art requires calm heads and hands, specialist training and strictly regimented handling protocols, with several people watching very closely, over the shoulder, following very detailed condition reporting and precise planning regimes.

Johannes Vermeer

Velázquez

Installation crew members link closely with exhibition designers, with the workshop teams that physically fabricate each tailormade exhibition space, and with the conservators who receive and care for the works during the build-up to a show. They also work closely with curators and lender representatives during artwork placements. For all an exhibition’s intra- and inter-gallery involvement, the install team is often the only one to physically handle the works.

On the floor, as a conversation with team members attests, calm, slow, conscious and synchronised movements go hand in hand with technical knowledge of securing and hanging the artworks. But the role is also about mutual trust, the occasional dress code for special jobs, and a modicum of flair. A guiding principle that prioritises the preservation of the artwork is perhaps where the common purpose of the lender, the host, and the installation team merges most clearly. As the QAGOMA team knows, while the job is to present works in a faithful and attractive way for our audiences, everything they do puts safety first, for themselves and for each object.

Apart from more obvious risks, if a work is off level by even a few millimetres and the inaccuracy isn’t picked up before, say, the blockbuster in which it hangs opens to the public, a lot of people will see it — and people do notice. Through the team’s professionalism and high standards, and an overlay of checks and balances, they aim to avoid that feedback.

A conversation with the QAGOMA Installation Team

Regardless of whether the work is an El Greco on display in ‘European Masterpieces from the Metropolitan Museum of New York’, or not, the team brings A-game focus and dedication to each exhibition changeover. Installation Officer Chris Booth, who coordinates the team — most of whom are artists (himself included), architects or otherwise arts-affiliated, working part time around their practice or discipline — feels a great sense of camaraderie and pride in their work. For other local artists in the team, especially, the rare opportunity to handle some of the Western canon’s most revered work was a chance to take their skills to another level, but it also provided quiet moments to study surfaces and details up close, and handle things very few people, through the centuries, have touched.

El Greco

For Matt Malone, a painter and student of architecture on the team, working on the installation of ‘European Masterpieces’ was an honour and privilege not to be taken lightly, and also highlighted the importance of personal processes and mindfulness while on the job:

In terms of actual working procedure, installation relies on precision and the repetition of a specific set of handling movements. Our pre-install preparation ensures the team establishes a focus early. From here, we follow a desire to continually finesse and perfect. I feel a bond is created between the staff involved during the install. Together, we complete a task way beyond the sum of our parts.

Maybe it’s the shared experience, or something of a deep understanding of what an artist goes through during a creative outpouring, that the collaborative process involving designers, curators and practising artists — from initial concept to slight modifications on the floor — can present a finished work to best effect. Honed by a sense of the exhibition-in-making as a kind of stage being set, where artists are characters whose scripts are on display, being on the team can also become a unique kind of performative role for some team members. As Matt Dabrowski, who creates works as The Many Hands of Glamour, suggests:

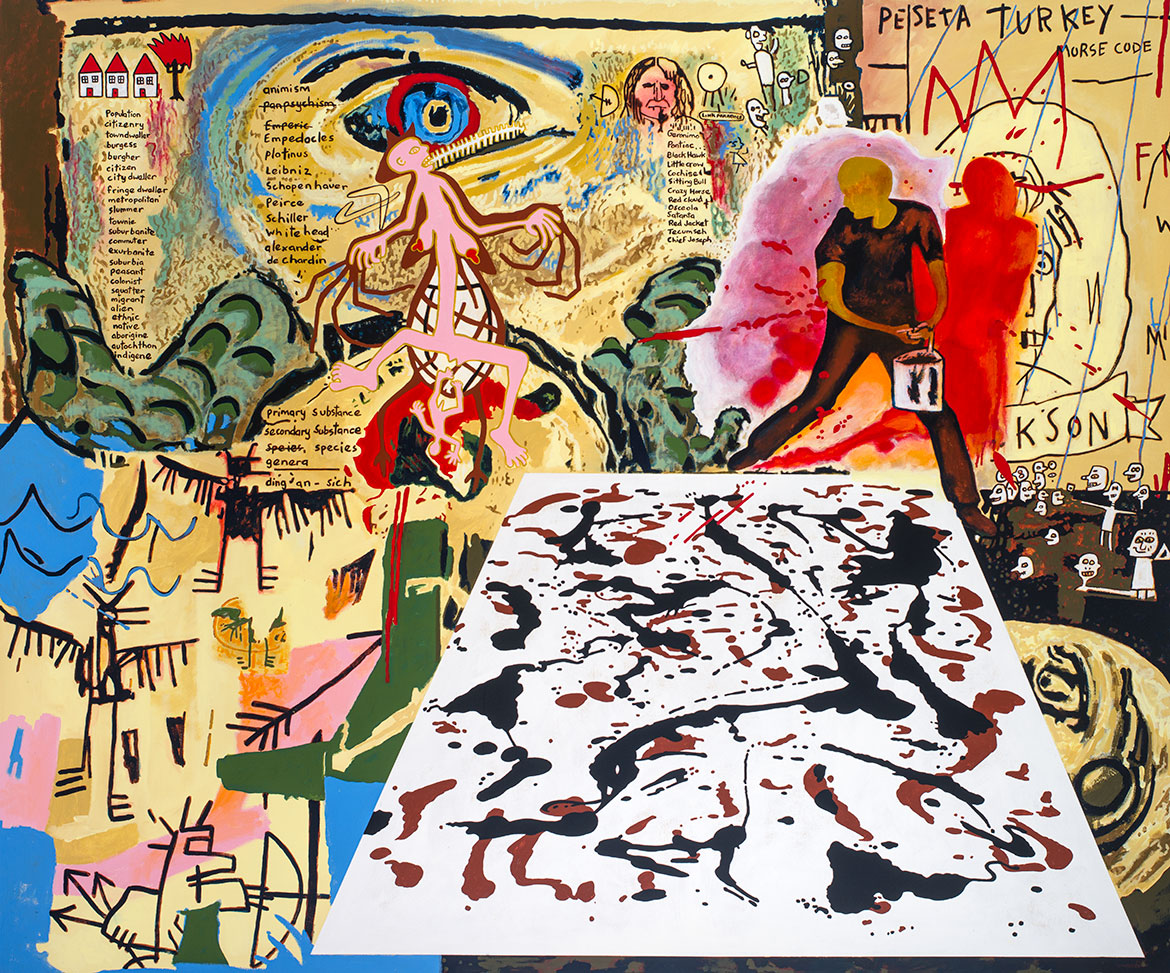

We present an artwork as faithfully as possible according to records and documentation that we have. But also, one of the more interesting roles of our install crew is to function as aesthetic interpreters, acting as hand of the artist, not present, by assisting and replicating the artist’s ‘style’ or ‘signature’. Like an actor takes on a role, another personality, the install crew assimilate, imitate and reproduce style, tones, textures and compositional arrangements or the ‘feel’ of the artist on show.

For Mark Birrell, working with like-minded, creative people in the crew is a form of exchange that motivates and inspires. He posits the skill sets he has brought from a background in interior, product design and manufacturing, have enabled him to adapt, give and gain value in terms of shared knowledge, and improve processes to foster versatility between departments. His sense that the team is part of an ecosystem of knowledge transfer is a common refrain among the team:

In terms of ‘unique’ attributes to becoming successful in the role, I believe there’s a couple that are universal: a genuine urge to succeed (GUTS), a belief that what you are doing is valuable, and a teachable attitude — you’re never too old to learn new things.

New York / Photograph: Anne Carter

There is a generosity of spirit, professionalism and technical ability, no matter what show they are working on, that sets the QAGOMA installation team apart, but their efforts often remain in the shadows. At a recent dinner hosted by Dr Mark Nelson, Chair of Art Exhibitions Australia, and attended by the Premier and Board of Trustees, for stakeholders, national media and partners involved in bringing the works from The Met to Brisbane, the installation team’s work was recognised by special guest Michael Gallagher — the Sherman Fairchild Chairman of the Department of Paintings Conservation at The Met — who spoke at length on his admiration for the team:

If there were an Olympics for installation, and I’m not a betting man, but I’d be putting my money on the Brisbane team for Gold. In particular, I want to thank the team with whom I have worked for the past ten days to install the show . . . they have been truly superb.

They are the best I have ever worked with in my career.

I was walking around at the end of the day, after a week, and I came across one of the installation team. He was standing transfixed in front of the El Greco painting — a really extraordinary picture — and he wasn’t at first aware of my presence. He was just saying ‘wow . . . wow’, and then he saw me.

He said, ‘You know what, I’ve never seen one in real life’. And I found it incredibly moving. I wrote back home, because our curators are incredibly passionate, and these works are their children, and it’s like they’ve sent their children somewhere else, and they get worried . . .

And so I said to them, ‘they’re not just in the hands of professionals here, they are loved here. They are being loved and cared for as we would’. And, I have to say, every one of them is being treated as a wow moment.

For Booth and the team, this high praise, along with the experience of installing ‘European Masterpieces’, has engendered new levels of respect for the team, among the team, and between institutions.

It really felt a privilege to represent the Gallery in a very real physical, technical sense, with the sheer scale of the canonical importance of these masterworks. It reminded us that we were intimately part of a long, ongoing

journey in caring for these artworks through the centuries. All in all, it was an honour and a privilege and, while at times stressful . . . we felt equals with colleagues handling absolutely magnificent works at such a high level of focus, with such a great and rewarding outcome.

May spirit levels continue to be high for the team, with congratulations from the wider QAGOMA family!

Simon Wright is Assistant Director, Learning and Public Engagement, QAGOMA

This Australian-exclusive exhibition was at the Gallery of Modern Art from 12 June until 17 October 2021 and organised by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in collaboration with the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art and Art Exhibitions Australia.

Featured image: The QAGOMA Installation team working with Rembrandt’s Flora c.1654, GOMA, May 2021 / Photograph: Anne Carter

#QAGOMA #TheMetGOMA