A captivating work by Pitjantjatjara law man and artist Timo Hogan — Lake Baker 2021 (illustrated) — unfolds the ancient religion within the Pukunkura (Lake Baker) landscape, for which he is cultural caretaker, and the narratives of the beings that shaped it.

ARTWORK STORIES: Delve into QAGOMA’s Collection highlights for a rich exploration of the work and its creator

Based at Spinifex Arts Project in the community of Tjuntjuntjara in the Great Victoria Desert, 650km north-east of Kalgoorlie, Timo Hogan was the first Spinifex artist and youngest artist overall — he was 48 at the time — to win the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards (NATSIAA) in 2021. Spinifex artists continue an artistic tradition centred outside the art market and firmly on Country.1 ‘Painting is important for Anangu (Western Desert Aboriginal people) to tell their stories’, explains Hogan. The Spinifex artists paint to tell the stories about their ancestral ties to the land — their traditional Country — and demonstrate their knowledge of the land through their art.2

Timo Hogan ‘Lake Baker’

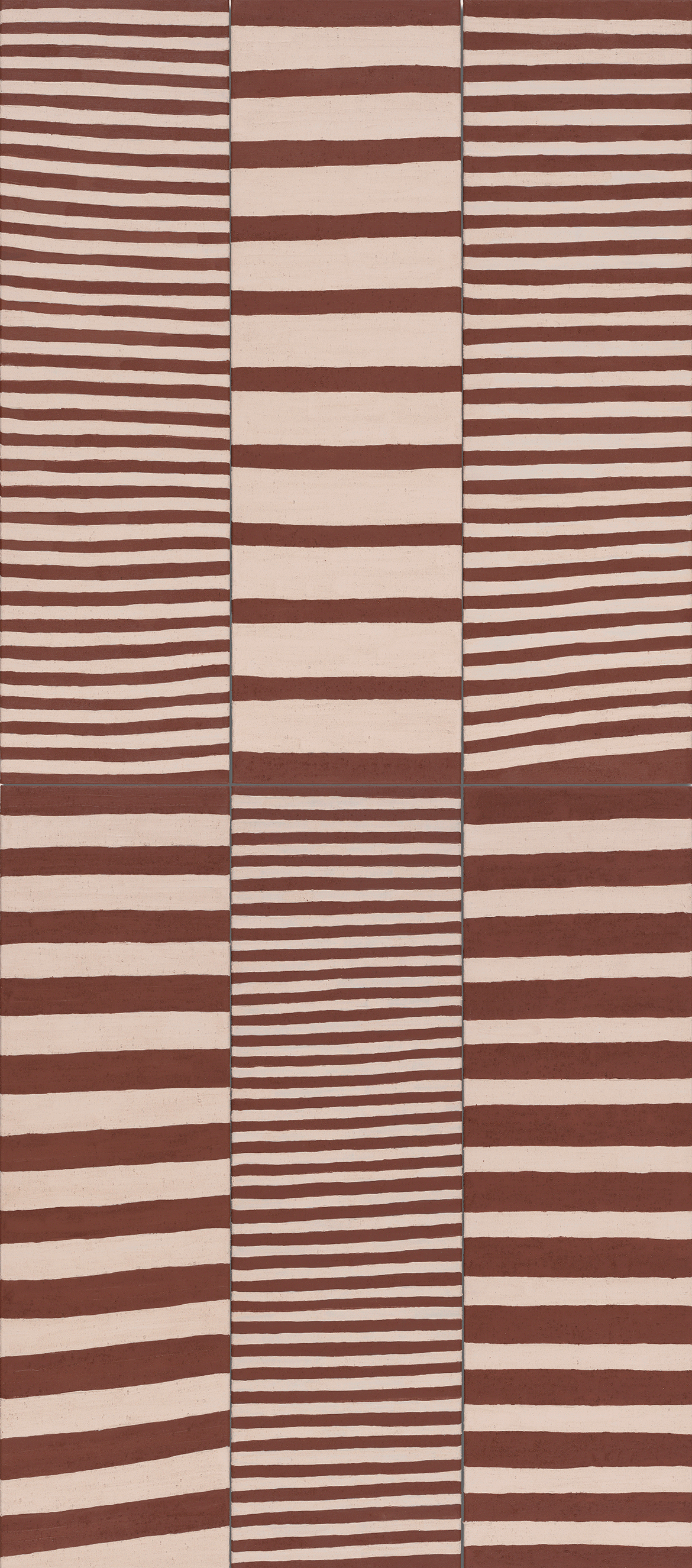

Since he began painting in 2004, Hogan has rendered the stories of ‘the vast and undulating landscapes’ of Pukunkura (Lake Baker), for which he is cultural caretaker.3 Through his work, Hogan unfolds the ancient religion within the landscape and the narratives of the beings that shaped it. In each iteration of Lake Baker, Hogan translates the Wati Kutjara Tjukurpa (Two Men Creation Line) of his birthright. Hogan’s artist statement speaks of the two men, depicted here as two black and white roundels in the lower third of the composition:

These two men watch carefully as the resident Wanampi (magical water serpent) departs his kapi ngura (home in the rock hole) and becomes the fearful, the all-powerful, as he skirts the edge of the lake, always watching, aware of the Two Men. These . . . Creation beings came before and shaped the environment as they moved through it, leaving indelible physical reminders of their power and presence for all to see.4

Deftly balancing a protocol of revealing and concealing, the painting depicts the sacred Tjukurpa of the lake, a major ancestral story from the region, which influenced the religious moral framework of its people for many thousands of years.5 Hogan can only divulge part of the story of this sacred site as it is considered extremely powerful and dangerous: it is strictly a men’s site, requiring ritual and song to show respect for the Wanampi.6

ARTISTS & ARTWORKS: Explore the QAGOMA Collection

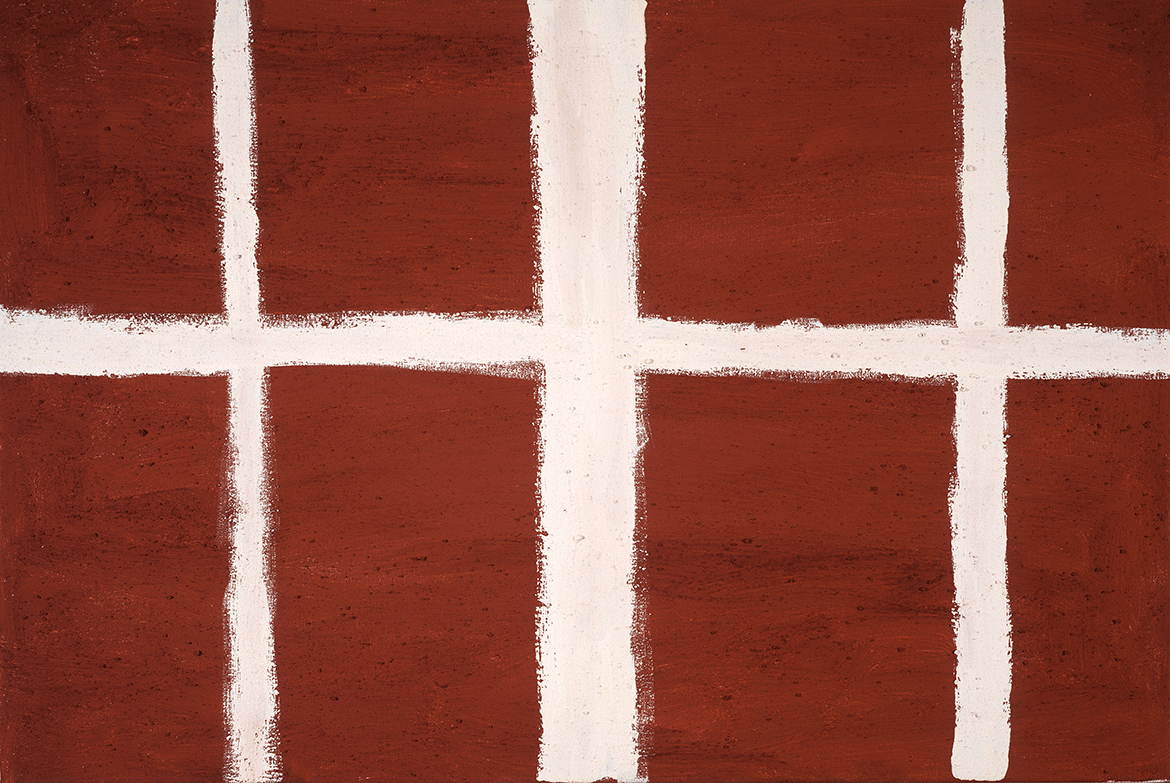

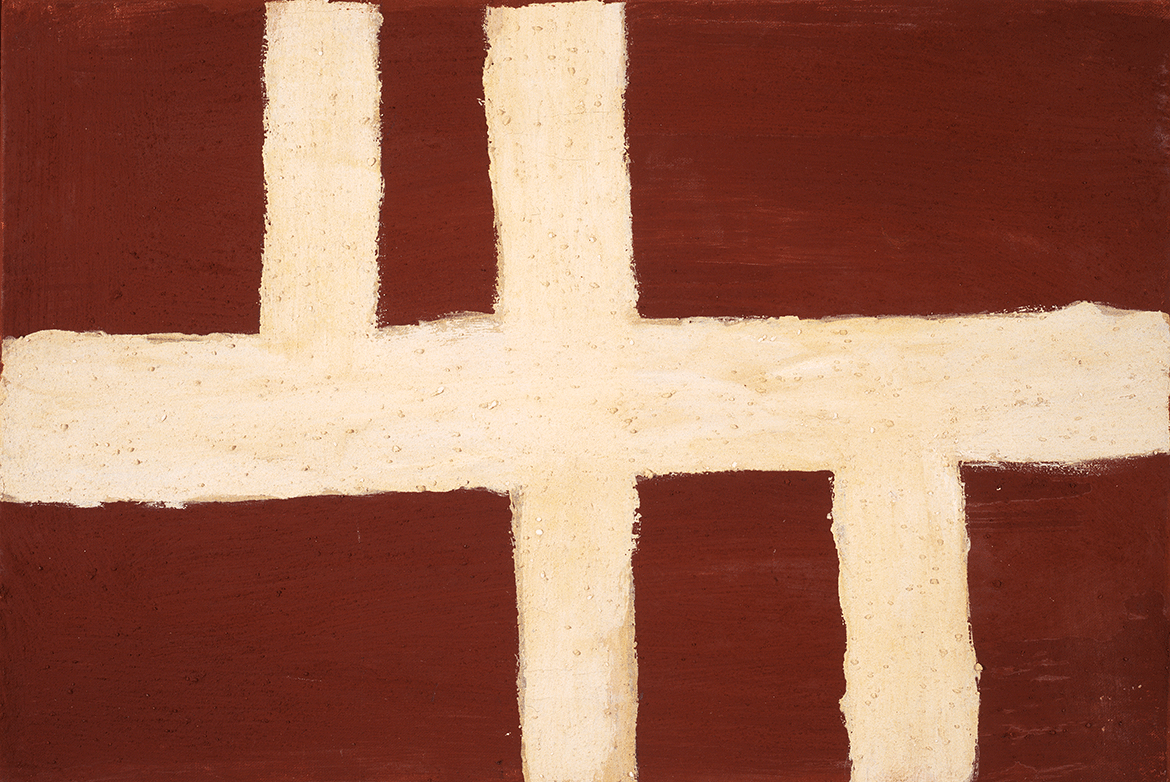

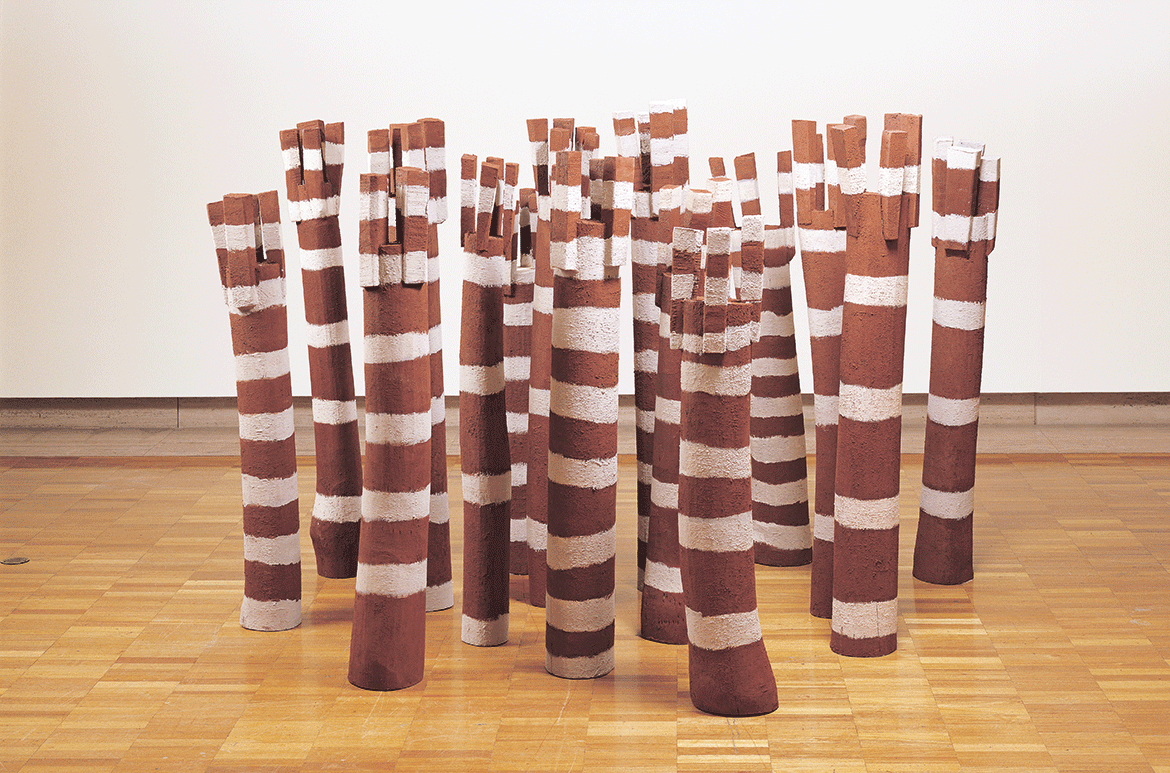

Hogan’s Pukunkura paintings are physical manifestations of stories traditionally told through performance; that physicality is present in his work in the forms and textures of layered paint against expansive black backdrops.7 Gesturally painted, often using a palette knife, these works evoke of the surface of the salt lake and ‘bring to life narratives of epic proportions — of creation beings shaping the environment they became part of — translating their movements into the landscape’.8

Hogan’s limited colour palette and bold compositional structure, reminiscent of Rover Thomas’s celebrated depictions of Country and visual traditions in the Kimberley, is unique among the explosively colourful paintings of his Spinifex contemporaries.9 Lake Baker has a grandeur that is exemplary of the artist’s dynamic practice and speaks to his deep connections to his Country and his reputation as one of ‘Australia’s most exciting up and coming artists’.10

Sophia Sambono is Assistant Curator, Indigenous Australian Art, QAGOMA

Endnotes

1 The painting of traditional Country created by these artists was to fulfil an ultimately successful land rights claim. The win made them the first group to ever be granted native title in Western Australia. See Ian Plunkett, ‘We celebrate this piece from Timo Hogan’, Japingka Gallery, accessed November 2021, https://japingkaaboriginalart.com/articles/we-celebrate-this-masterpiece-from-timo-hogan/

2 Emma Joyce, ‘Australia’s prestigious NATSIAA winners have been announced’, Broadsheet, 6 August 2021, accessed November 2021, https://www.broadsheet.com.au/national/art-and-design/article/winner-australias-most-prestigiousnational-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-art-awardshas- been-announced

3 Matt Ward, Rawa Nyinanyi – unbroken [exhibition catalogue], Outstation Gallery and Spinifex Arts Project, Parap, NT, 2016, pp.44–6.

4 & 5 Certificate of Authenticity, Spinifex Arts Project.

6 & 7 Brian Hallett, Pantjutjara – Timo Hogan [exhibition catalogue], Spinifex Arts Project and Outstation Gallery, Darwin, 2021, p.6.

8 Brian Hallett, ‘I’m the boss now; Timo Hogan Returns to Lake Baker’, Australian, accessed November 2021, https://www.theaustralian.com.au/weekend-australian-magazine/im-theboss-now-artist-timo-hogan-returns-to-lake-baker/newsstory/9bf5c66270af40882566f2793237d65f

9 Plunkett.

10 Alicia Perera, ‘Remote WA artist wins top prize in national Indigenous art awards’, ABC News Online, 6 August 2021, accessed November 2021, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-08-06/natsiaa-indigenous-art-awardswinners/100356866

Lake Baker 2021 is on display in ‘North by North-West’ in Gallery 2 at the Queensland Art Gallery, 11 February 2023 – 2 March 2025

Acknowledgment of Country

The Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land upon which the Gallery stands in Brisbane. We pay respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander elders past and present and, in the spirit of reconciliation, acknowledge the immense creative contribution Indigenous people make to the art and culture of this country. It is customary in many Indigenous communities not to mention the name of the deceased. All such mentions and photographs on the QAGOMA Blog are with permission, however, care and discretion should be exercised.

#QAGOMA