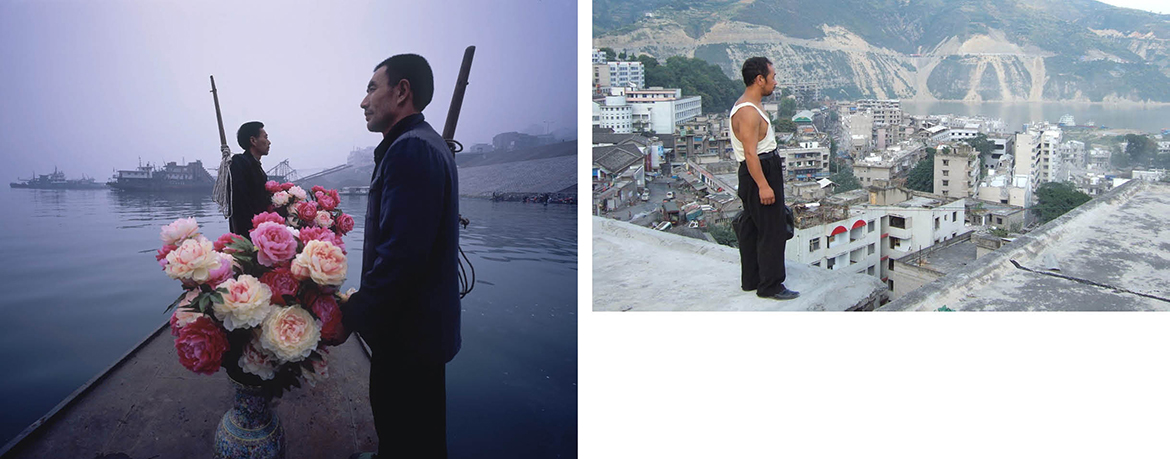

To celebrate the centenary of the 16mm-gauge film format, ‘Colour Box’ brings together a selection of contemporary and archival 16mm experimental films to highlight the format’s long-standing relationship with abstract cinema. The free screenings are in response to the exhibition ‘Living Patterns: Contemporary Australian Abstraction’ at the Queensland Art Gallery from 23 September 2023 – 11 February 2024.

Free screenings this week & upcoming

Hand-painted explosions of colour, affectionate exchanges between vertical and horizontal lines, and playful dancing silhouettes are all brought to life in magnificent symphonies of abstraction, courtesy of the 16mm film format.

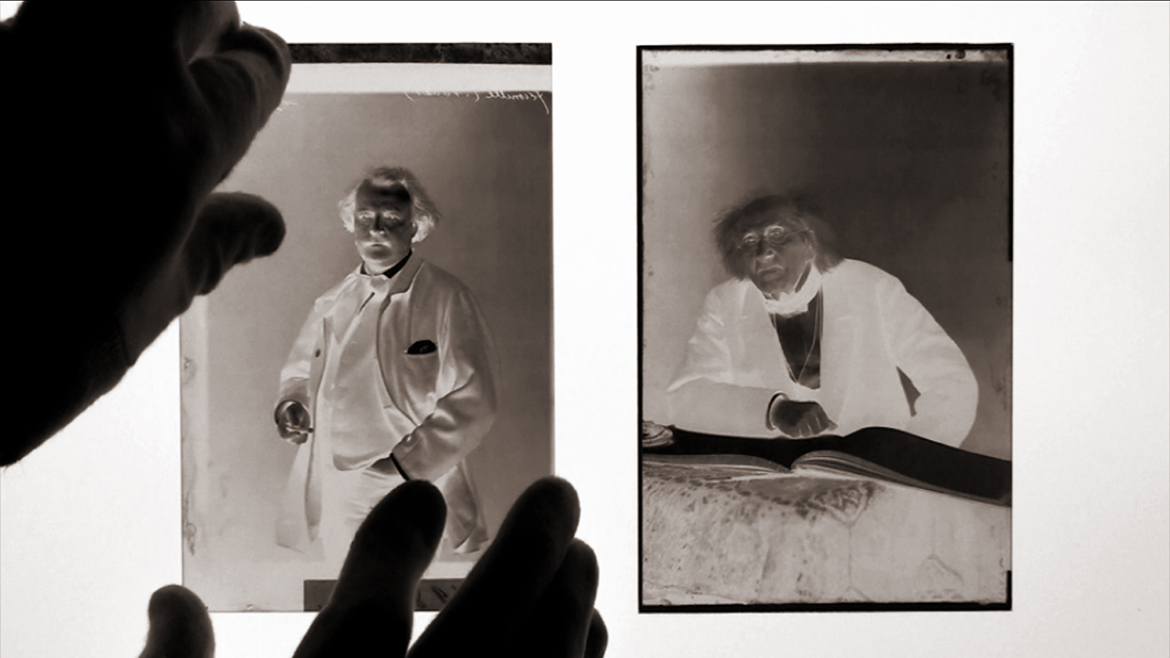

The nostalgia of cinema lies not only in the pictures that we see on screen, but also in the sounds and smells of the mechanical devices that bring the cinematic illusion to life. For filmmakers, projectionists and cinema aficionados, one of the most evocative scents of cinema is the distinctly vinegary fragrance of degrading film emulsion. The reason for this is that, since their inception in the late 1800s, flexible film stocks have used gelatin emulsion (a technology originally developed by the photographic industry) to adhere images to film. Despite the apparent permanency of this alchemical process, from the moment a print is struck, material film — particularly the 35mm and 16mm gauge formats — begins to deteriorate, serving as a fragrant reminder of the fragile nature of material film and traditional cinema.

Dawn Chorus 1979

A few decades after the first 35mm screenings, film manufacturers (charmed by the spectacle of the 35mm format but disenchanted by its high price-tag and bulky weight) began to investigate more accessible and commercially viable formats. This led to the creation, in 1923, of the 16mm gauge — a smaller, lighter and cheaper format developed by Eastman Kodak, which gave emerging filmmakers the opportunity to explore the possibilities of film without the burden of cost. Its affordability and availability made it one of the first democratic film formats, and it quickly found a home among artists, amateur filmmakers and the avant-garde.

Diagonal Symphony 1921

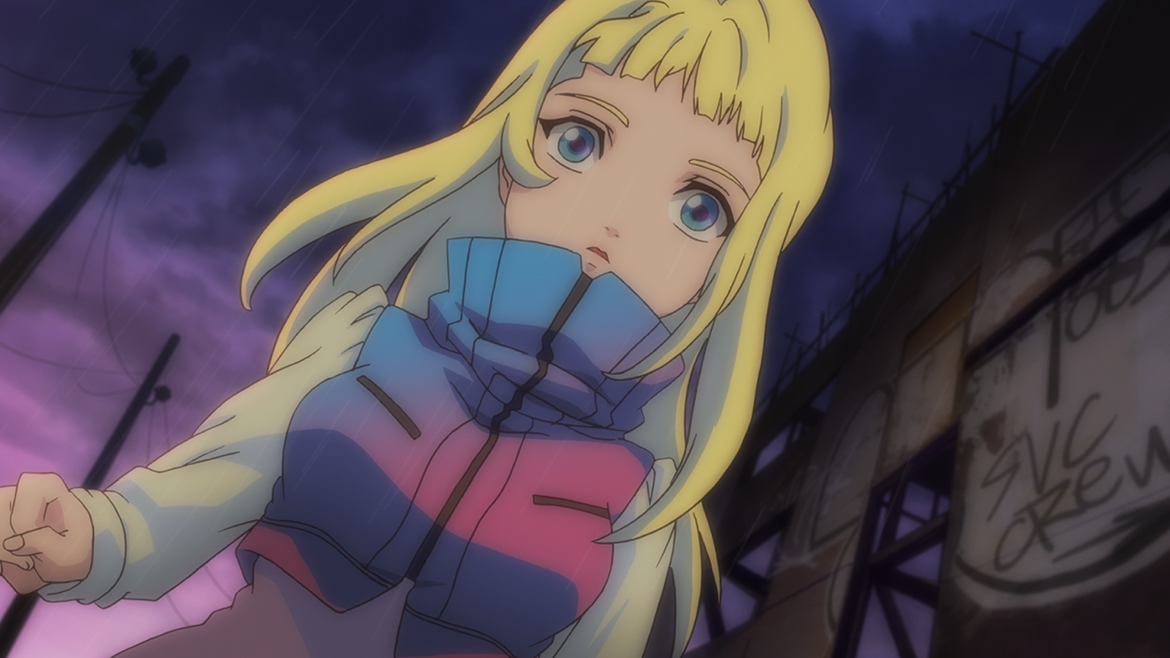

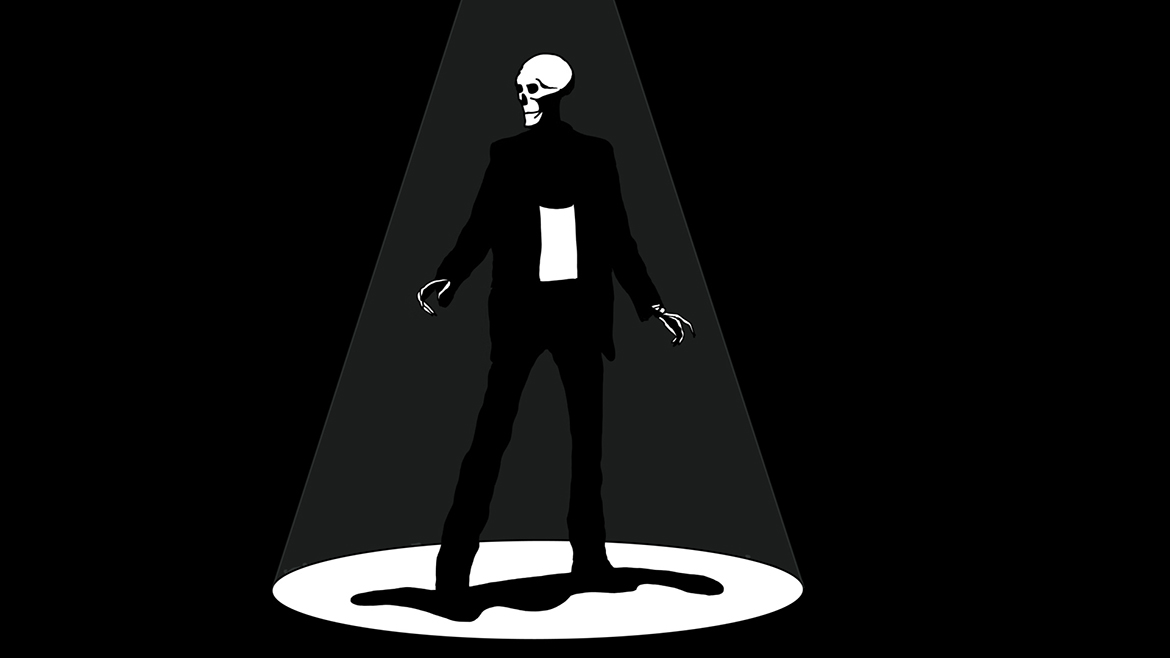

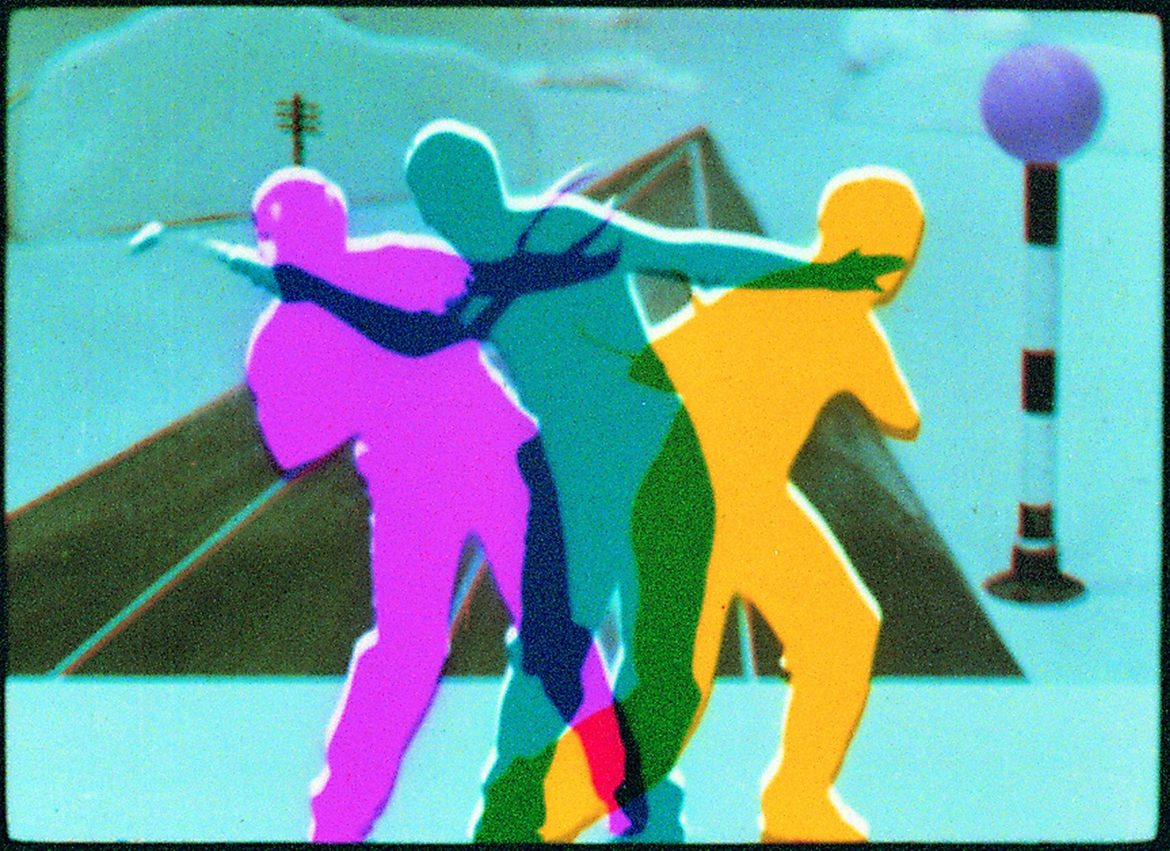

Around this time, the art movements of Modernism, Futurism, Dadaism and Expressionism were fast becoming prevalent in Europe, giving rise to a new wave of creative thought that favoured expression over representation. Intrigued by the ability of the moving image to expand on these contemporary ideas, filmmakers such as Walter Ruttmann, Viking Eggeling, Hans Richter and Oskar Fischinger began to experiment with shapes and forms, often hand-painting 16mm celluloid, which resulted in a new style of experimental filmmaking that would later be known as ‘abstract cinema’.

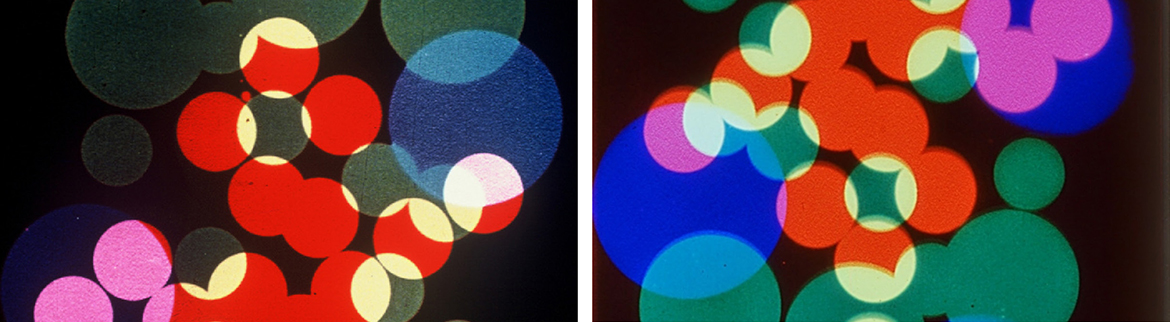

Kreise (Circles) 1933

Several years later, music and colour became increasingly prominent in this style of filmmaking. Led by pioneering New Zealand filmmaker Len Lye, these early experiments (disguised as cinema advertisements) became spectacular playgrounds for onscreen displays of movement and colour. Filmmakers Mary Ellen Bute and Norman McClaren extended much of the richness of this style of filmmaking into the postwar period, harnessing the undeniable joy of abstraction to provide audiences with a welcome source of visual splendor.

Rainbow Dance 1930

Over time, these experiments in abstraction became more performative, moving the genre further into the realms of repetition and perception. Filmmakers from around the world, such as Hollis Frampton, Malcolm Le Grice, Michael Snow, and Corinne and Arthur Cantrill, used changes in motion, frame rate and camera positioning to purposefully challenge audiences with unexpected visuals and abstract narratives. In the 1970s and 80s, abstract films became even more participatory through the introduction of text, taking the form of visual ‘puzzles’ that would offer new ways to see and experience film. While this style of filmmaking was largely reflexive, it could also be unexpectedly autobiographical, as demonstrated by Barbara Hammer’s 1988 film Endangered, which combines images of the artist with the process of film production itself.

Euclidean Illusions 1979

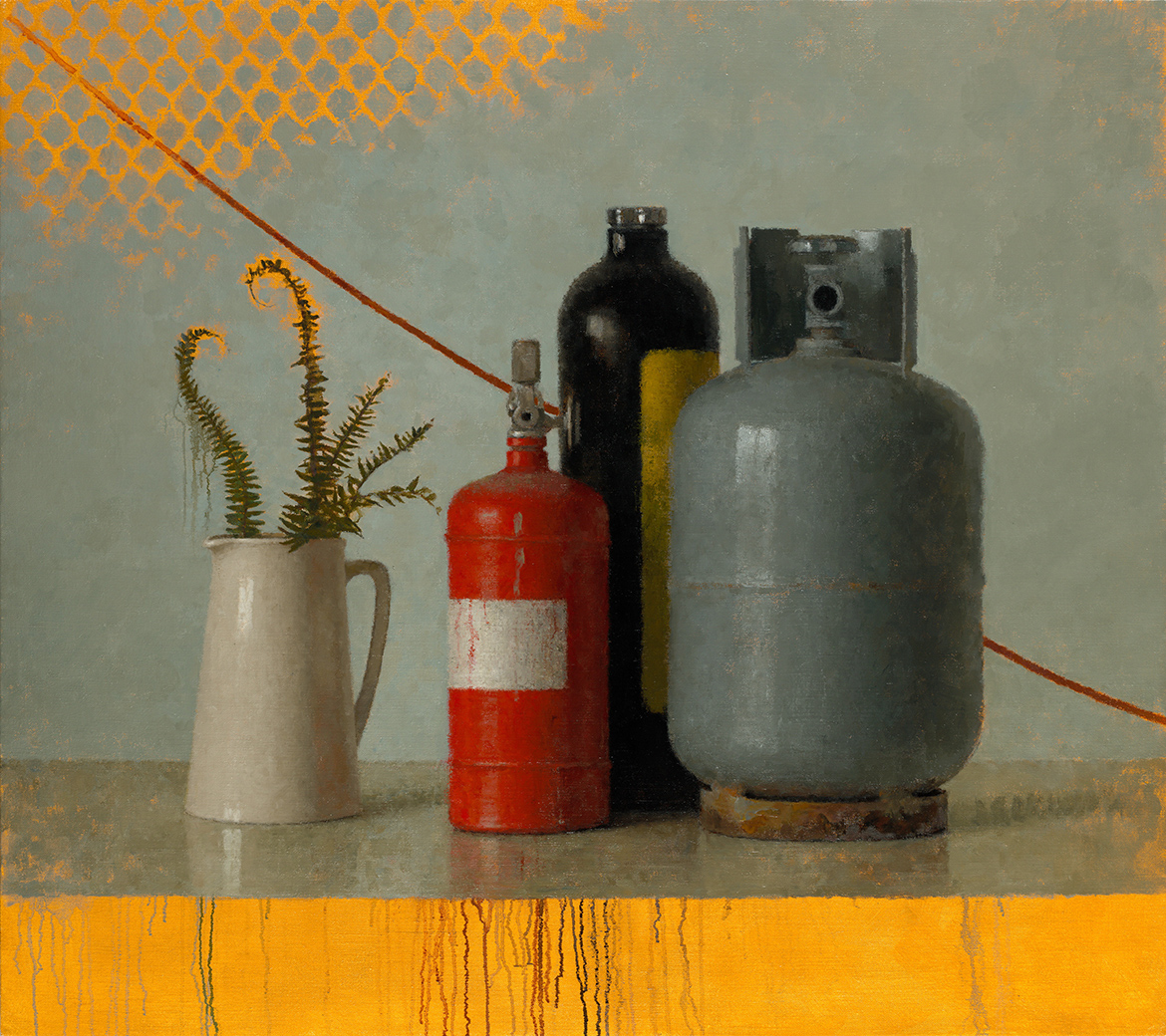

As abstract cinema continued to evolve, so did the technology around it. The introduction of computer-generated imagery opened never-before-seen dimensions for these onscreen abstractions, moving them in to more expansive, geometric territories. Filmmakers John Whitney and Stan VanDerBeek, who each had a penchant for exploring the slippages between art and technology, were quick to adopt this form of onscreen abstraction, resulting in an array of films filled with intricate patterns and mathematical dreamscapes. This fascination with abstraction and technology would extend long into the 1990s and early noughts, as shown through the work of experimental filmmaker Joost Rekveld.

Although not as prevalent as it once was, and despite the rise of digital technologies, the 16mm format remains an important tool in the development of new ideas and experimental films. Many artists prize the medium for its unique qualities, such as a vivid colour palette and its ability to be drawn on directly — Australian filmmaker Dirk De Bruyn, for instance, continues to incorporate hand-drawn and hand-painted 16mm elements into his films. The kaleidoscopic effects of abstraction have also been used in new and increasingly poignant ways by artists such as Kent Morris to reconstruct built environments through a First Nations lens.

Colourful, playful and disarmingly mesmeric, ‘Colour Box’ offers a unique opportunity to explore the rich history of this chapter in experimental cinema by celebrating its highly expressive and immersive aesthetic on the big screen.

#11, Marey Moiré 1999

Victoria Wareham is Assistant Curator, Australian Cinémathèque, QAGOMA

Colour Box

‘Colour Box: Abstract Cinema’ screens in the Australian Cinémathèque, GOMA and the Queensland Art Gallery Lecture Theatre / 24 September 2023 until 4 February 2024.

Living Patterns

‘Living Patterns: Contemporary Australian Abstraction’ is on display in the Queensland Art Gallery’s Kenneth and Yasuko Myer Gallery (Gallery 3), Gallery 4 & Watermall from 23 September 2023 – 11 February 2024.

#QAGOMA