Gordon Bennett (1955–2014) created the triptych Bloodlines 1993 early in his career. It speaks of colonial violence and the consequences of being on the ‘wrong’ side of history, purchased in 2019, this powerful and sobering work is a major acquisition for the QAGOMA Collection.

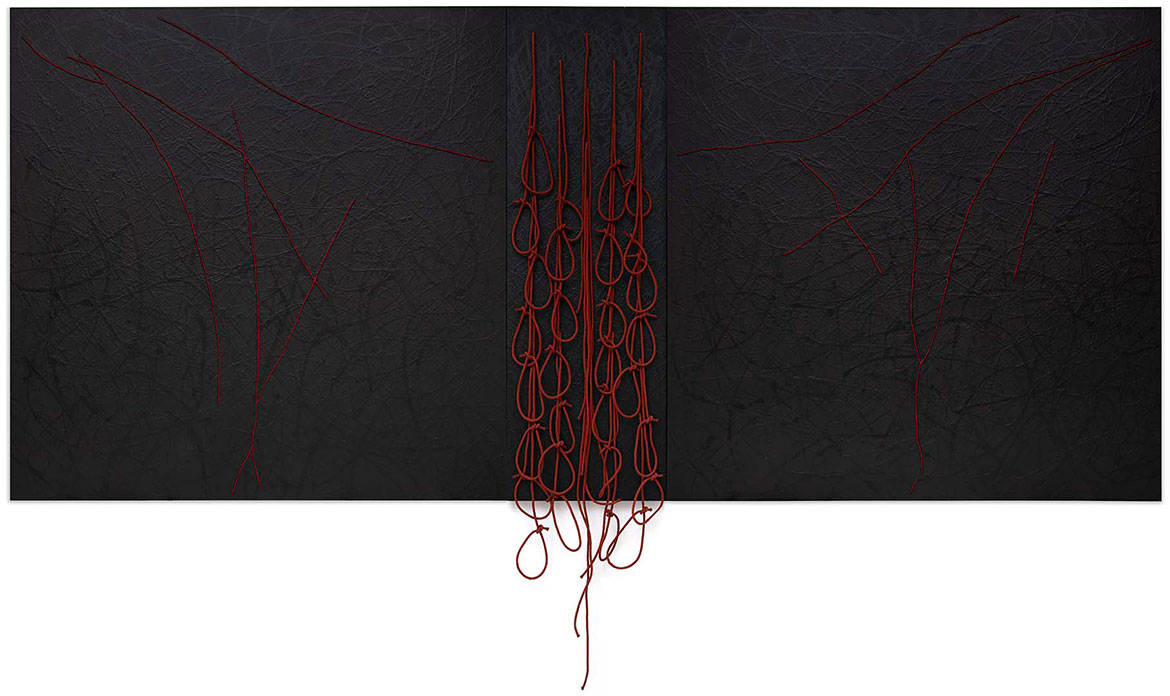

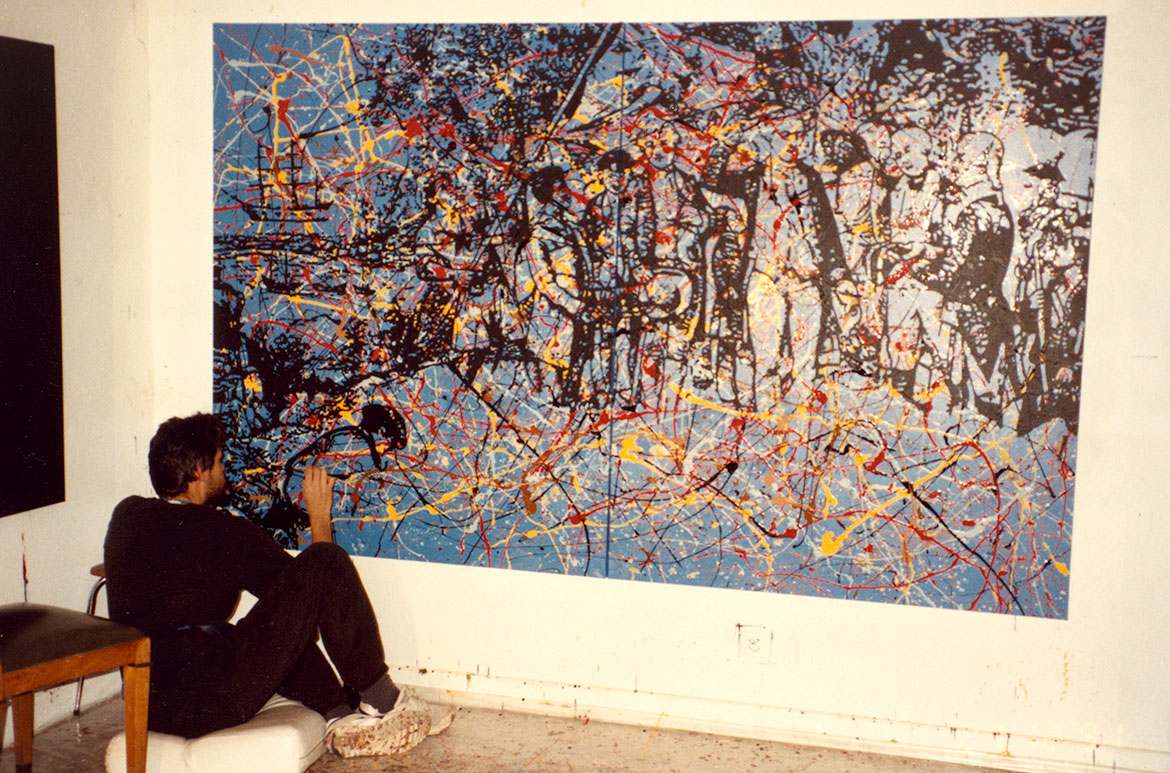

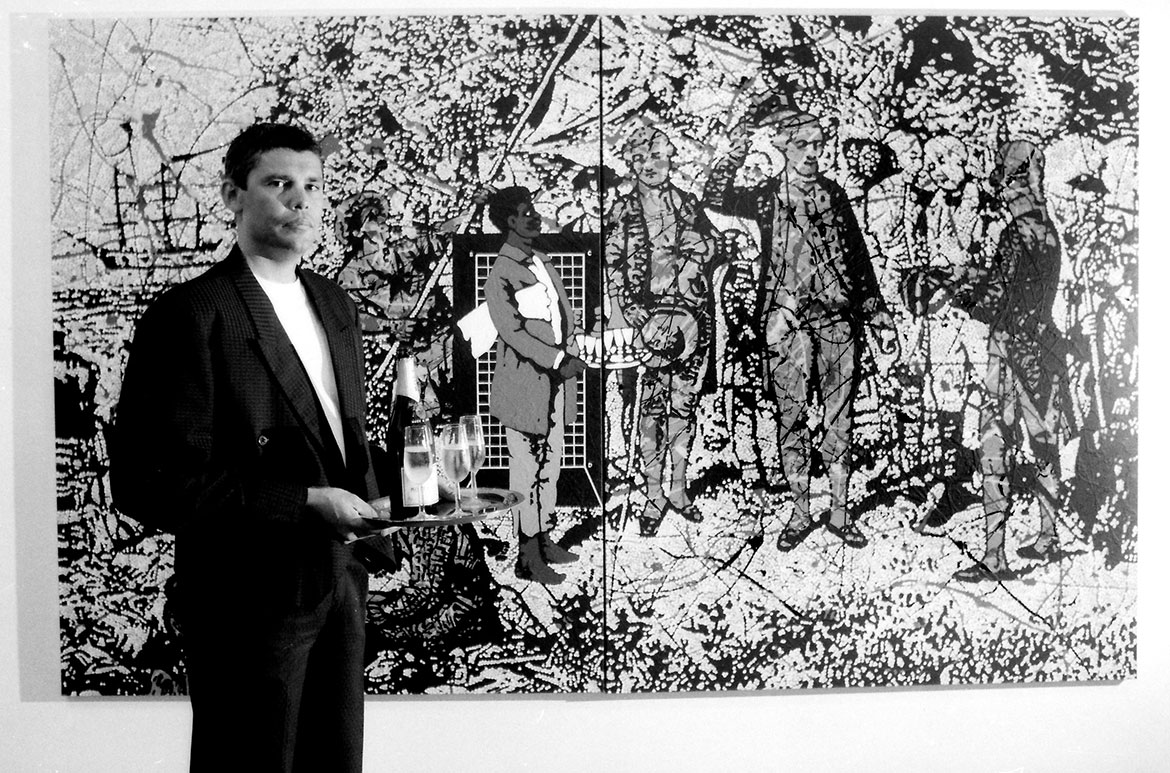

‘Bloodlines’

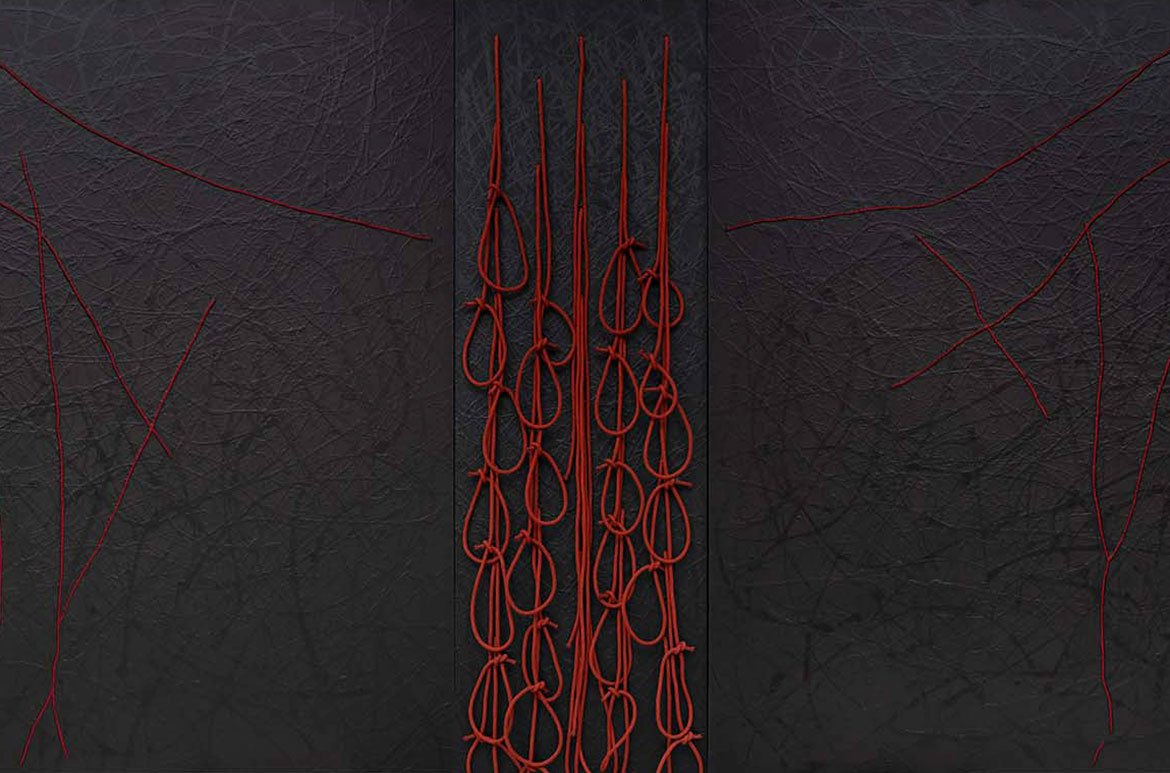

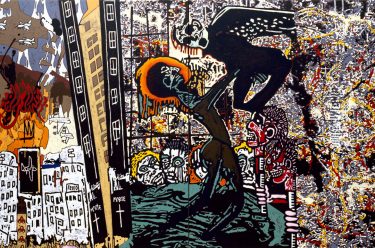

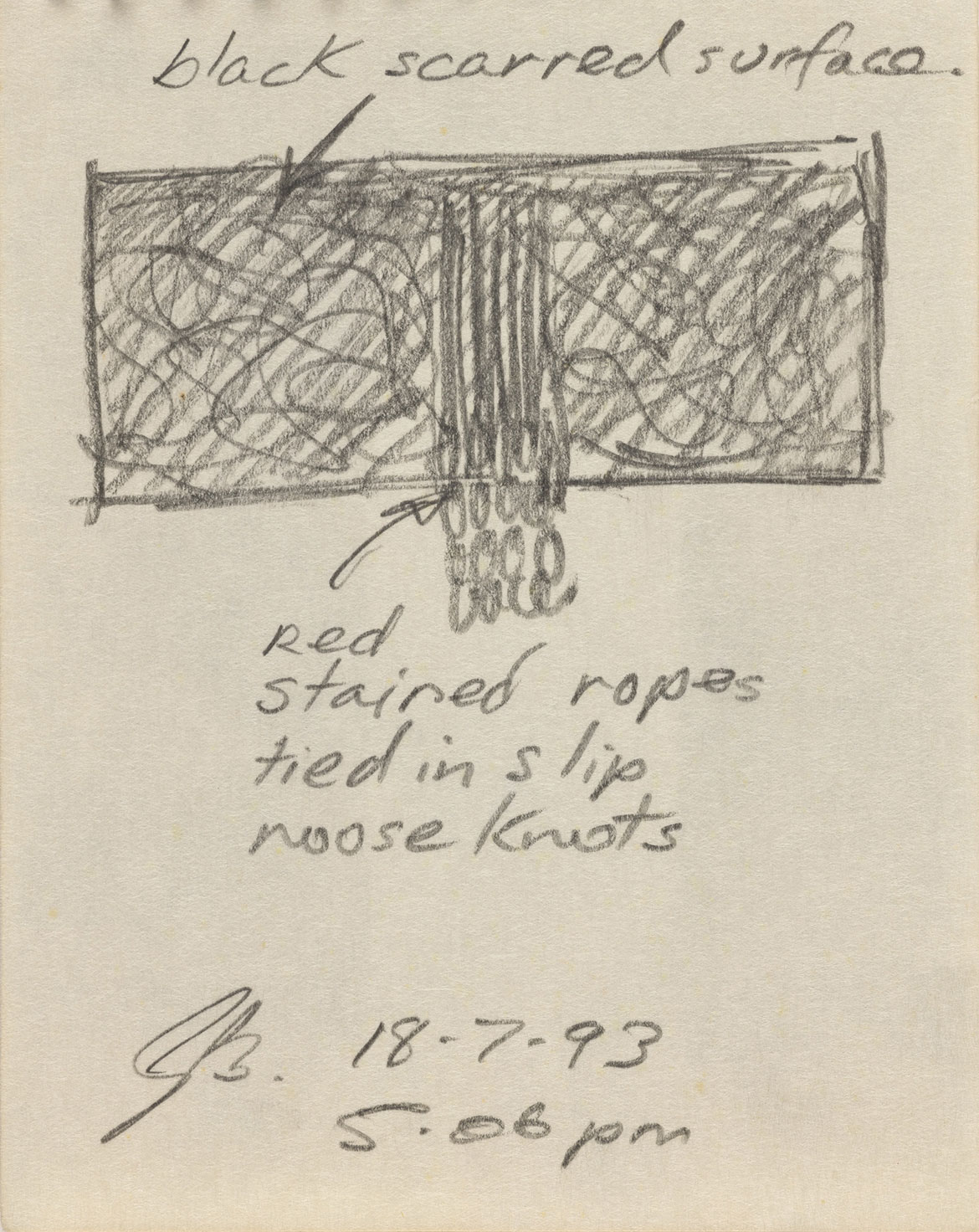

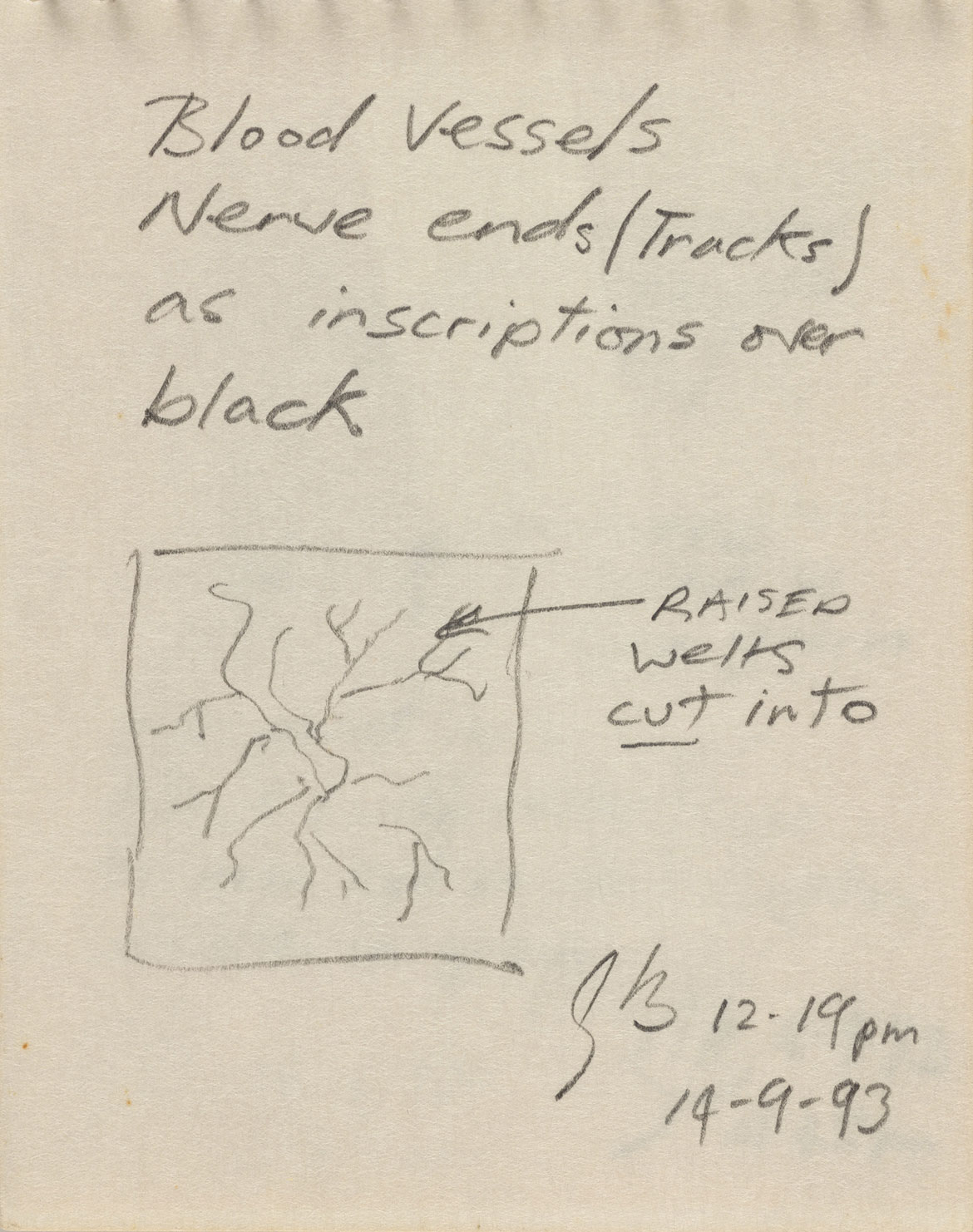

Preliminary sketches for ‘Bloodlines’

In his lifetime, Bennett was widely regarded as one of Queensland’s, and indeed one of Australia’s, most perceptive and inventive contemporary artists. After exhibitions at Brisbane’s Bellas Gallery and Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art in the late 1980s, Bennett was promptly included in major national events such as ‘Perspecta’ at the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1989, the Art Gallery of South Australia’s Moët & Chandon Touring Exhibition, the ‘Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art’ in 1990, and the landmark ‘Balance 1990: Views, Visions, Influences’ at the Queensland Art Gallery (QAG). Given the difficult nature of his primary subject matter — the overlooked and unresolved crimes of Australia’s colonial period, and the persistent racism that has followed into the present — Bennett’s early and sustained success is testament to the intellectual and aesthetic relevance of his practice and the authenticity of his expression.

Bloodlines is an early triptych that relates to Bennett’s ‘welt’ series of paintings, which is somewhat underrepresented in critical discussions of his practice. Bennett embarked on this body of work in France in December 1991 during the 12-month travel scholarship he was awarded through the Moët & Chandon Australian Art Fellowship he won that same year.1 At this time, Bennett frequently referenced the ‘drip technique’ of American abstract expressionist Jackson Pollock, sometimes using it to invoke a tangled web of history. More than a compositional device and clever art reference, he used the visual matrix of these netted drips to represent the narrative of destiny and sense of entitlement that cast Western colonial expansion across the globe. This same narrative also served to frame the First Nations people they encountered as primitive, in a state of nature which, by extension, served to rationalise that their lands were empty and therefore ripe for ‘civilisation’.2

RELATED: Delve deeper into the art of Gordon Bennett

SIGN UP NOW: Be the first to know. Subscribe to QAGOMA Blog for the latest announcements, acquisitions, and behind-the-scenes features.

The key QAGOMA Collection work Untitled 1991 is an excellent example of Bennett’s appropriation of Pollock. Brown lashes of paint are surrounded by a field of black and white dots that depict a colonial sailing ship braving a storm. In the lower half of this field, seven decapitated Aboriginal heads in red strike a pattern reminiscent of the composition used in The Raft of the Medusa 1818–19 by French Romantic painter Théodore Géricault. Géricault’s original memorialises, if not sensationalises, a tragic group of withered survivors from the shipwreck of the French naval frigate Méduse. Crucially, however, while Géricault’s original subjects float on rough seas, Bennett’s seem bound to the turbulent field itself, unable to resist the waves of Western culture that engulf them.

Bennett’s scenario incorporates his view that Pollock was an inheritor and beneficiary of the colonial mindset, primarily for his heavy debt to the otherwise marginalised Navaho sandpainting tradition. Though he was most likely sincere in his intentions, neither Pollock nor his promoters questioned the binary perspective of the civilised white innovator channelling the raw and primitive forms of an unsophisticated other.3

Exploring Pollock from another angle, in the ‘welt’ works, Bennett buried his drips under a uniform dark monochrome paint-skin. As he explains in reference to the first such example,

. . . this created a surface which looked remarkably like an illustration of the scarified back of an African slave I later saw reproduced in a book about the representation of Blacks in the nineteenth century; the title of the triptych was A Typical Negro, 1863.4

With the ‘welt’ pieces I wanted to convey the wounding of the human spirit, its scarification; the overpainted Modernist trace of a Pollock skein as metaphor for the scar as trace, and memory, of a colonial lash . . . It may be argued that in taking this position I am portraying black people as victims. This was indeed my intention and I wanted not only to ‘play the victim’ but to take it further and use that energy to advantage by not resisting, or trying to display strength, but to show pain and how much it hurts, even to the extent of self-mutilation.6

While the monochrome overpainting in Bloodlines clearly references the skin of People of Colour and the history of violence directed toward them in the patterns of scarring, there is also an art historical precedent in the Russian avant-garde artist Kazimir Malevich and his black square paintings. Malevich’s gesture was a long-running preoccupation for Bennett, as he explains:

Malevich was most certainly trying to get beyond the medieval, denominational, religious confines of such [Russian] icons to a kind of

spiritual ‘essence’ that was common to all humanity. I certainly have no quarrel with that, and I admire Malevich very much, but it is clear that in reality black and indigenous peoples, as people considered ahistorical — trampled, enslaved, exploited and discarded, their lands confiscated and wealth plundered over five hundred years of colonialism — were not to be joining Europeans on their great journey to that glorious sunset and spiritual culmination waiting for humanity just over the horizon line.7

Bennett’s monochrome fields weren’t simply painted over; they were also cut, revealing a blood-red wound. This visual allusion to the body locates the violence inflicted in the present as much as the past. It heightens the consideration of inheritable aspects of such vicious, sustained violence as widespread trauma. While the scale of Bloodlines and its cuts is engulfing, the near symmetry of their patterns recalls the lines found in the palm of the hand. In fact, close associates of the artist have confirmed that these markings are based on Bennett’s own palms. This, too, suggests violence as something carried and inherited, and perhaps the desperate and dramatic expression of staring at one’s empty hands. On this, Bennett stated: ‘In this [gesture] I am drawing on Aboriginal funeral ceremonies in which ritualised public displays of grief and mourning can involve bloodletting and cutting one’s own body’ — though, notably, he also cited the precedent of Argentine–Italian painter Lucio Fontana and his cut canvases.8

The narrow centre panel of Bloodlines, composed of a cluster of red oxide-stained and purposefully knotted ropes, conjures the visceral image of looping veins. A more literal interpretation, however, would be a field of hanging nooses. Vigilante justice in the form of lynching was not uncommon in the southern United States. In Australia, however, massacres or ‘dispersals’ were generally carried out with gunfire.9 This ambiguity might suggest that Bennett was making a more contemporary and local reference to Aboriginal deaths in custody. Hanging deaths of Aboriginal people in custody were shockingly common in Australia during the 1980s, and were a key statistic in the call for a Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody report commissioned by the Hawke Government in 1987.

It is conceivable that the use of symmetry was also intended to recall a flayed figure, and perhaps the Crucifixion. Although oblique, the notion is reinforced by the use of the triptych format, which arose from early Christian art and the tradition of three-panel folding altar paintings. Similarly, the title ‘Bloodlines’ might evoke the history of the Stolen Generations, and specifically the impact of eugenics and assimilationist policies. These were often supported and administered by the church, which allowed for the destruction of families and the erosion of tradition by asserting that Aboriginal parents had no right to their children, who could be taken by the government without cause. Furthermore, the memory of pernicious public discussions of the implications of mixed blood, and alienating follow-on questions of who can reasonably claim an authentic Aboriginal heritage — or, inversely who might be able or allowed to pass for being white on a measure of appearance or ancestral percentages — would also appear to provide relevant historical context to Bennett’s powerful gesture.

Constructed by drawing on a wide variety of potent historical sources, Gordon Bennett’s extraordinarily searching and intellectually supple work Bloodlines seeks to better acknowledge the largely ‘hidden’ or ignored history of colonial violence in Australia, and its continuing burden on the present. Crucially, Bennett has taken great pains to include the frame of the binary mainstream narratives of black/white, primitive/civilised in his picture, and to include the consequences of this thinking on those people who are rendered less than. Sombre and even grotesque, Bloodlines attempts to shock a broad audience into an empathetic state, and jolt them into understanding the notion of ‘peaceful settlement’ as a myth.10

‘Unfinished Business: The Art of Gordon Bennett’ was in the Marica Sourris and James C. Sourris AM Galleries (3.3 and 3.4), Gallery of Modern Art from 7 November 2020 until 21 March 2021.

Peter McKay is Curatorial Manager, Australian Art, QAGOMA

Endnotes

1 Gordon Bennett, ‘The manifest toe’, in Ian McLean and Gordon Bennett, The Art of Gordon Bennett, Craftsman House, Sydney, 1996, p.48.

2, 3 Bennett, pp.44–7.

4 Bennett, pp.48.

5 ‘A typical negro’, Harper’s Weekly, 4 July 1863, p.429.

6, 7, 8 Bennett, p.50.

9 Lorena Allam and Nick Evershed, ‘The killing times: The massacres of Aboriginal people Australia must confront’, Guardian, 4 March 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/

australia-news/2019/mar/04/the-killing-times-themassacres-

of-aboriginal-people-australia-must-confront,

viewed 22 July 2019.

10 Bennett, p.53.

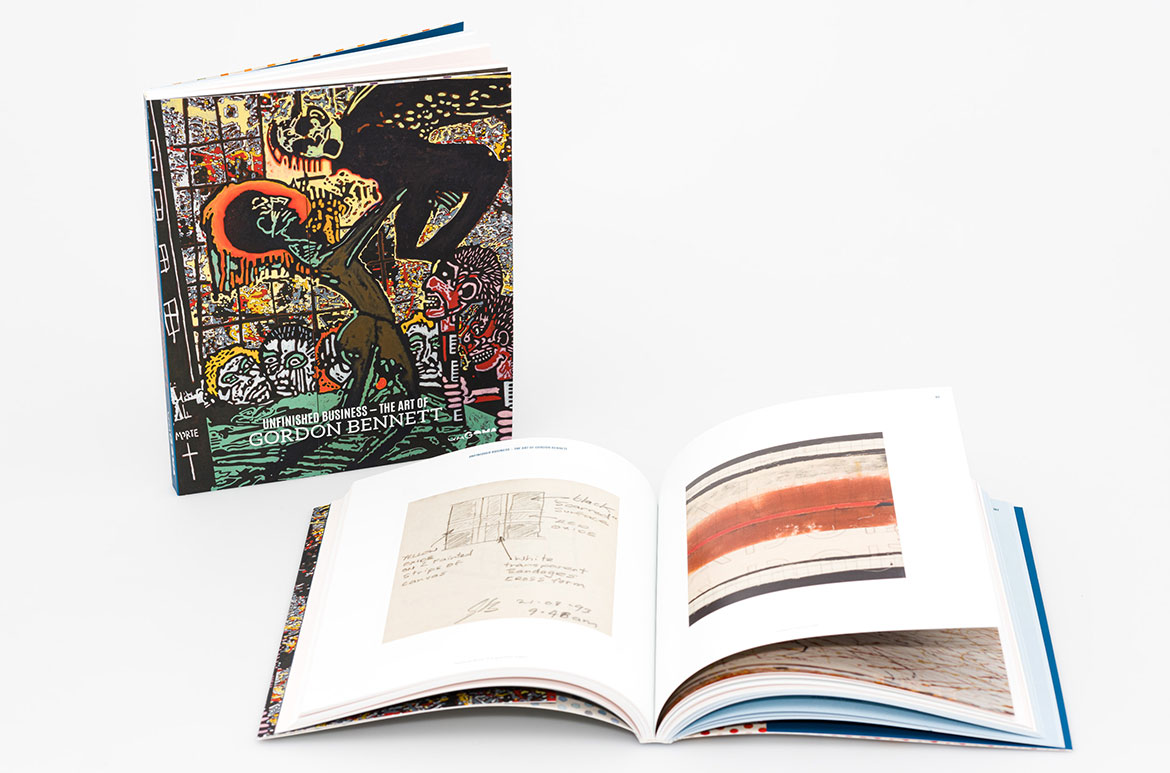

The publication

At 200 pages and with more than 120 colour illustrations, Unfinished Business: The Art of Gordon Bennett includes works created from the 1980s to 2014 sourced from studio, public and private collections, including early installation works; Bennett’s ‘history’ paintings; mirror paintings, De Stijl works; his ‘Home décor’ series; ‘Notes to Basquiat’ works; abstract ‘Stripe’ paintings; and late works showing renewed engagement with political contexts. Pages from the artist’s personal notebooks, as well as archival photographs provided by the Gordon Bennett Estate, provide intimate insight into how the artist worked. The publication has been sponsored by the Gordon Darling Foundation.

Know Brisbane through the Collection / Read more about Australian Art / Subscribe to QAGOMA YouTube to go behind-the-scenes

Acknowledgment of Country

The Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land upon which the Gallery stands in Brisbane. We pay respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander elders past and present and, in the spirit of reconciliation, acknowledge the immense creative contribution Indigenous people make to the art and culture of this country.

It is customary in many Indigenous communities not to mention the name or reproduce photographs of the deceased. All such mentions and photographs are with permission, however, care and discretion should be exercised.

Featured image detail: Gordon Bennett Bloodlines 1993

#GordonBennett #QAGOMA