Leaving his Chinese hometown of Quanzhou, Cai Guo-Qiang began wandering the world to experience life outside China. Around three decades later, the powerhouse artist is riding the crest of his career, and has created an enigmatic exhibition at the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) involving two brand new commissions.

‘Falling Back to Earth’, the first solo exhibition by Cai Guo-Qiang at the QAGOMA, invokes the spirit of Tao Yuanming (Tao Qian, 365–427), an ancient scholar–official who turned his back on government duty and returned ‘home’ to a life of reclusion in nature. His poems of rustic living and rural utopia have inspired Chinese brush‑and‑ink painters for centuries. In this exhibition, the shift of emphasis in Cai’s work away from gunpowder drawings and explosion events (representing the symbiosis of destruction/creation) towards a more grounded engagement, with motifs drawn from the natural world, might be regarded as a sign of middle-aged mellowing. It’s also in part a belated conceptual homage to the artist’s father, whose style of calligraphy and ink painting, with its emphasis on harmony and balance in emulation of the workings of the cosmos, Cai eschewed early on as he forged his own artistic path. Perhaps there’s also a desire to minimise risk, recalling how his large‑scale explosive and fire and water events planned for the 1996 and 1999 Asia Pacific Triennials were thwarted. In the sculptural installations Head On 2006 and two new commissions — Heritage (illustrated) and Eucalyptus (illustrated), both 2013 — Cai instead employs objects to focus attention not on the brilliant moment of detonation but on the fallout, effect or cost of violence caused by human actions, seen or unseen.

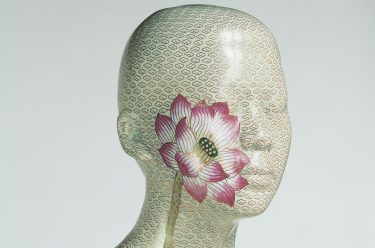

Cai Quo-Qiang ‘Heritage’ 2013

Cai Quo-Qiang ‘Eucalyptus’ 2013

RELATED: Cai Guo-Qiang’s ‘Heritage’

At an early stage in his artistic career Cai Guo-Qiang sought to understand and find his own place in a world that extended beyond his hometown and his motherland. In 1981, he left Quanzhou in Fujian (a front line province in the ongoing conflict between China and Taiwan) to study stage design at the Shanghai Theater Academy. At the end of his studies he went ‘wandering’ in far-north-west China, to Buddhist cave sites in Luoyang and Dunhuang, to the Muslim areas of Xinjiang, and to Tibet. He wanted to ‘create myself’, as he says, ‘by placing myself in Mother Nature and ancient cultures’.1 Five years later, in 1986, he travelled to Japan to study, became fluent in Japanese and went on to establish an international career as an artist. A decade later he relocated his life and studio to New York, which remains his primary base today.

Cai Guo-Qiang has worked with many of the world’s leading museums and galleries and with many different communities. He has garnered numerous international awards and is one of the most recognised figures in contemporary art.2 In acknowledgment of his stature as a mainland China‑born global artist, he was appointed Director of Visual and Special Effects for the opening and closing ceremonies of the 2008 Summer Olympic Games in Beijing. Cai’s explosion events are grounded in the materials and philosophy of China, where gunpowder was invented. The Beijing Olympics represented a creative homecoming of sorts, a high profile international event that brought the artist into a complex alliance with official China.

Gunpowder trials

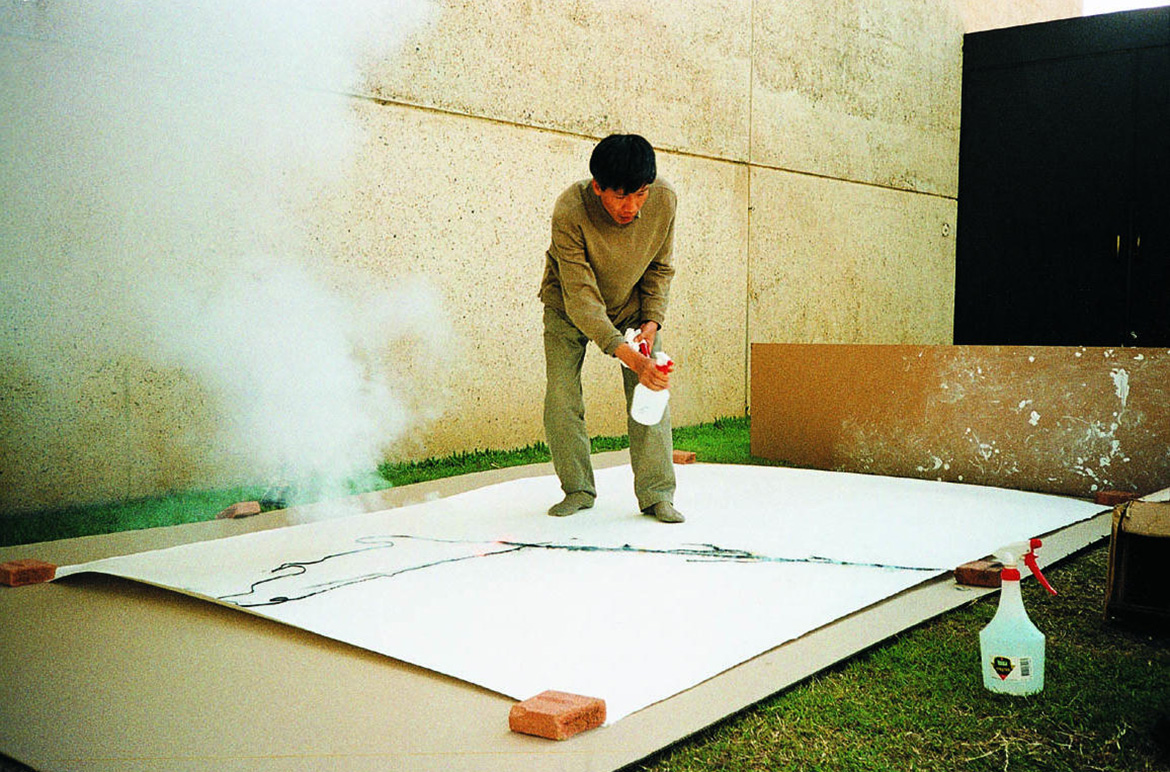

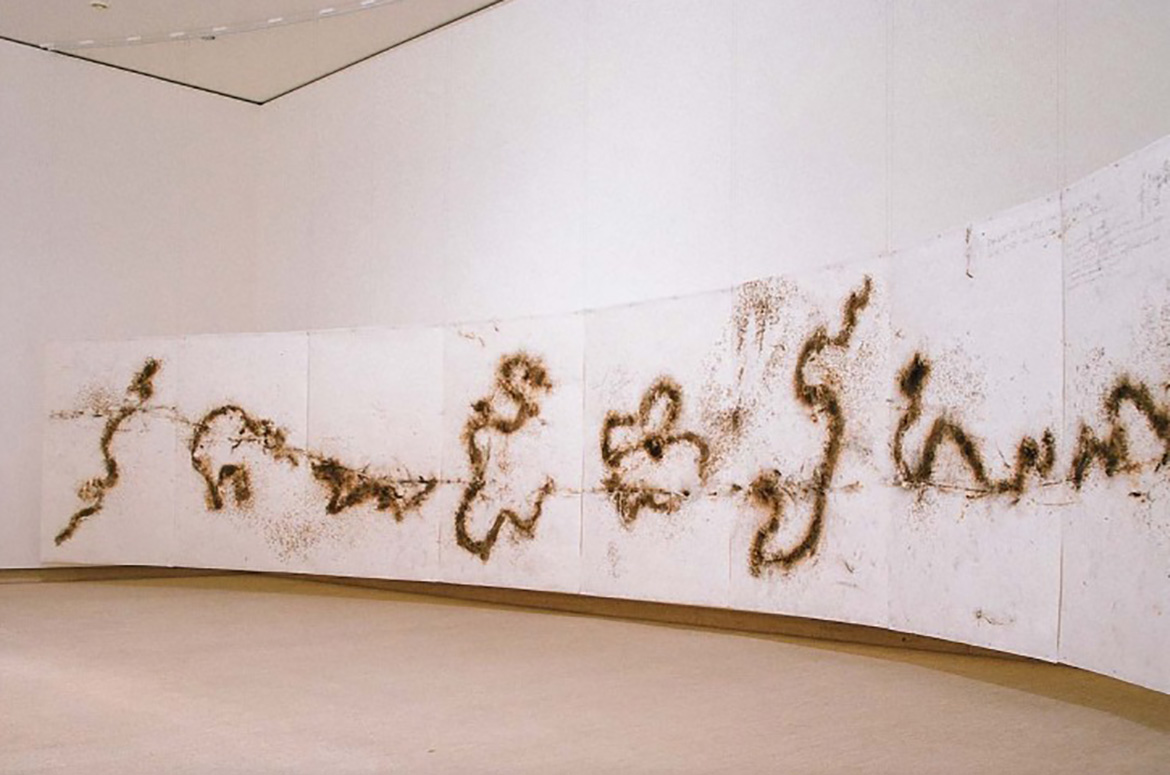

Cai Guo-Qiang ‘Dragon or Rainbow Serpent’ 1996

RELATED: Cai Guo-Qiang’s gunpowder drawing

Among Cai Guo-Qiang’s early works are two haunting self-portraits that employ gunpowder on canvas and convey humanistic interests that extend beyond his own immediate experience. Shadow: Pray for Protection 1985–86, created in Shanghai prior to his move to Japan, is concerned with the devastating effects of atomic warfare — the bombing of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945.3 In a scene that approximates Hell, mutilated bodies are strewn across a dark landscape, trapped within the shadow of an American B-29 bomber. The plane that wrought the carnage is also depicted in profile at the top right of the canvas, with a ruined clock stopped at 11.02am, the precise time of the explosion. These products of human ingenuity and invention are balanced by a white dove (a prayer for peace) that hovers in the upper right above a portrait of the artist who is witness to the horror. The dove and the artist appear like apparitions conjured from the darkness, their spirit conveyed by traces of pigment left by the fluttering wings of a live bird against the canvas. It is an unusual work by a Chinese artist in the way it transcends national boundaries and political rhetoric through its expression of empathy towards non-Chinese subjects. The second work, Self-Portrait: A Subjugated Soul 1985–89, also created prior to leaving China, was reworked in Japan after the 4 June massacre of 1989 and given its current subtitle.4 A charred stick figure — a spirit figure — emerges from the canvas, daubed with dull red and green pigment that bifurcates the body. The figure is illuminated by a halo of light and appears to emit sparks of energy, suggesting perhaps the ultimate triumph of the human spirit in the face of brute force. In an interview in Tokyo in 1990, Cai said:

The Tian’anmen Incident had an enormous impact on my soul. I was forced to change the directions of so many plans… It made clear the problems of the destinies of the era that humans face, and of immutable fate… A quest for one’s self is equal to a quest for the universe.5

With the birth of his daughter that same year, Cai and his wife, Hong Hong Wu, remained in Japan, with a sense of both hope and responsibility for the next generation. It was their fate.

Cai’s explosion events, conducted outdoors in the presence of an audience, began in earnest in 1989. Human Abode: Project for Extraterrestrials No.1 took place in a park outside Tokyo on 11 November 1989. A tent — described by Cai as a yurt of the kind used by nomads in Central Asia, but not unlike the tents that provided shelter for hunger strikers in Tian’anmen Square less than six months earlier — was the site of an explosive event. The damaged structure was dismantled, reinstalled in a nearby ancient shrine and displayed for a week as an act of commemoration.

Cai Guo-Qiang ‘Dragon or Rainbow Serpent’ 1996

Cai’s interest in gunpowder and explosions relates to their association with the Big Bang or the origin of life rather than its more violent connotations. He uses gunpowder to communicate with the universe and to heal the effects of human activity in the world. In Chinese, gunpowder is huoyao, meaning ‘fire medicine’. A chance encounter with theoretical physicist, cosmologist and author Stephen Hawking at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 1990 provided an opportunity for dialogue, intensifying the artist’s exploration of concepts of deep time and space in his creative practice. The three works that comprise ‘Falling Back to Earth’ are linked by the implied interrelationship between human beings, nature and art. Head On, originally created as a site-specific work for the Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin, is a massive installation of 99 wolves that run through the air in a tight pack. Oblivious to danger, they crash, one after the other, into a glass wall the exact height and thickness of the Berlin Wall.6 The wolves fall to the earth injured, only to rise and return to repeat what appears to be an instinctive, self-destructive action. The two new installations were inspired by his experience and understanding of Australia. Eucalyptus comprises a mighty Queensland gum tree that was to be felled to make way for urban development. Displayed in a museum setting, the tree appears as a fallen sentinel, compelling the viewer to confront our complicity in its abject fate. Similarly, Heritage presents 99 replica animals from around the world (including dingoes and kangaroos) gathered at a pool of water as if for their final drink. An incessant dripping sound draws attention to the preciousness of water, the source of all life. Unlike an old-fashioned museum diorama that recreates lost human or natural heritage as miniaturised containers of memory, Cai has enlarged the size of the animals and removed all boundaries between what is past and present, making the viewer occupy the same space as the animals and highlighting the interconnected fate of all of us who inhabit planet Earth.

While no explosive events are associated with ‘Falling Back to Earth’, Cai did create a thematically related gunpowder drawing titled Homeland in Shanghai on 25 September 2013, marking the first Christie’s auction in mainland China. Christie’s obtained its licence to operate there — the first granted to an international auction house — in April 2013, after French billionaire Francois-Henri Pinault (whose family owns Christie’s) agreed to repatriate two bronze sculptures, originally looted during the destruction of the Summer Palace by foreign powers in 1860. (Pinault had purchased the sculptures following Christie’s stymied attempt to auction them as part of the collection of late French fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent in 2009.)7 Cai Guo‑Qiang’s large, eight-panel landscape was created inside the Union Church (now regularly used for art exhibitions) before an audience of influential art executives. The force of the explosions, recorded by witnesses on their mobile phones, created a picturesque blast image of old Quanzhou, Cai Guo-Qiang’s hometown. The gunpowder drawing was later sold for charity at the inaugural auction, realising 15 million yuan (A$2.6 million), more than Picasso’s Homme assis (Seated man) 1969, which fetched 9.6 million yuan (A$1.6 million). The proceeds of the sale will contribute to the construction of the Quanzhou Museum of Contemporary Art (QMoCA), designed by Frank Gehry. The museum is part of ‘Everything is Museum No.4’, one of Cai’s community based projects, and will function as an integrated site for temporary exhibitions, artist residencies and performances. With this museum project in his hometown, the life and art of Cai Guo-Qiang come full circle. Through the awe-inspiring scale and real‑life staging of the museum, Cai gives back to the community that nurtured him, returning from the stratosphere and falling back to earth.

Dr Claire Roberts is Senior Lecturer in Art History at the University of Adelaide. She has worked closely with Cai Guo-Qiang and QAGOMA on the Asia Pacific Triennials of Contemporary Art.

Endnotes

1 Primeval Fireball – The Project for Projects, P3 Art and Environment, Tokyo, 1991.

2 The most comprehensive catalogue of Cai Guo-Qiang’s work to date is Thomas Krens and Alexandra Munroe, Cai Guo-Qiang: I Want to Believe, Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2008. The exhibition opened in New York and travelled to the National Art Museum, Beijing, and the Guggenheim, Bilbao, in 2008–09.

3 Krens and Munroe, catalogue 3, pp.84–5.

4 Krens and Munroe, catalogue 2, p.83.

5 Cai Guo-Qiang + P3, Primeval Fireball.

6 The latter was effectively breached by the citizens of East Berlin on 9 November 1989, reuniting the two parts of the city that had been divided during the Cold War. Later presentations of this work retain the height but not the thickness of the Berlin Wall.

7 The Chinese government had unsuccessfully tried to block the sale and the highest bidder was a Chinese national who refused to pay on the grounds that the objects were looted. In order to diffuse the high profile case the sculptures, valued at US$40 million, were acquired by Pinault. The bronze heads of a rat and a rabbit (two of the 12 animals of the Chinese zodiac) were looted in 1860 by British and French forces during the Second Opium War, taken from Haiyan tang — a Western-style palace, designed by Jesuit artists, in the Garden of Perfect Brightness (Yuan Ming Yuan, the main imperial pleasance for much of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911)). See Edward Wong and Steven Erlanger, ‘Frenchman will return to China prized bronze artifacts looted in nineteenth century’, New York Times, 26 April 2013, <http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/27/world/europe/frenchman-will-return-to-china-prized-bronze-artifacts-looted-in-19th-century.html>

Featured image detail: Cai Guo-Qiang Heritage 2013

#QAGOMA