In the early 2000s, senior Wik and Kugu law men from the Aurukun region on the west coast of Cape York Peninsula, Far North Queensland, pioneered a significant contemporary movement: They reimagined their ceremonial visual traditions as contemporary art. Embodying ancestral narratives in a way that maintains spiritual and historical connections between the past and present, this new approach to art fostered an indispensable intergenerational exchange.

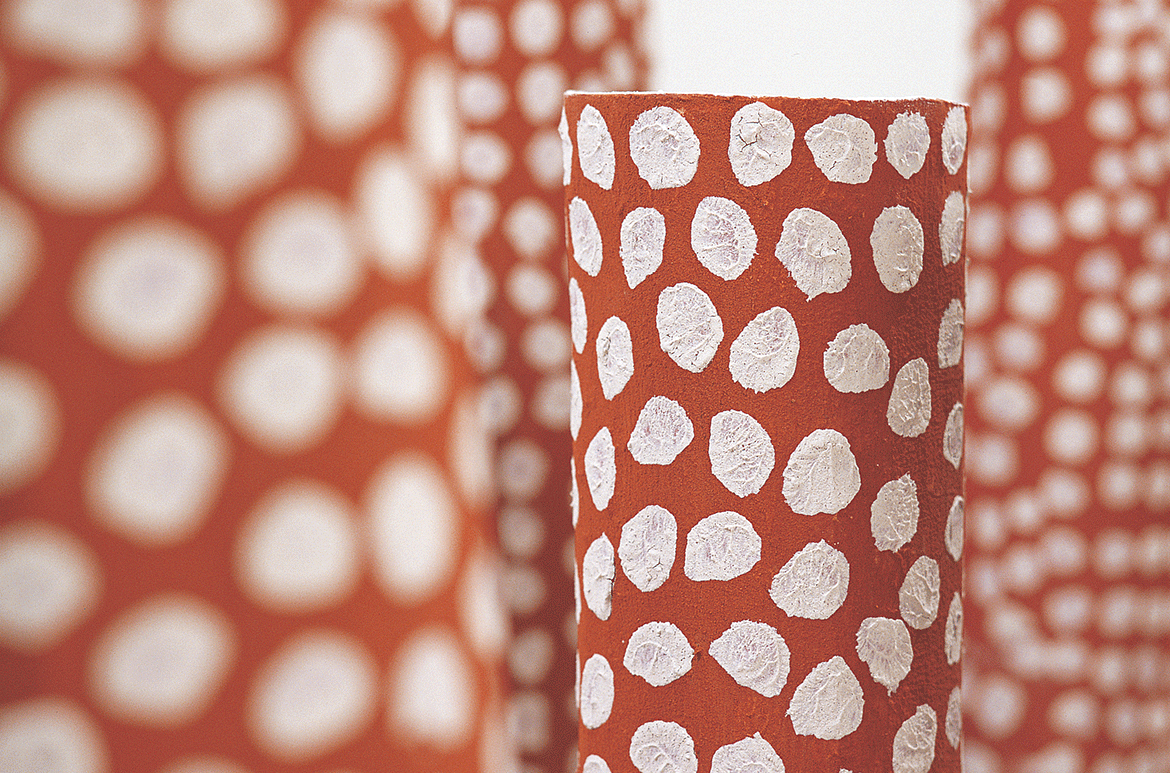

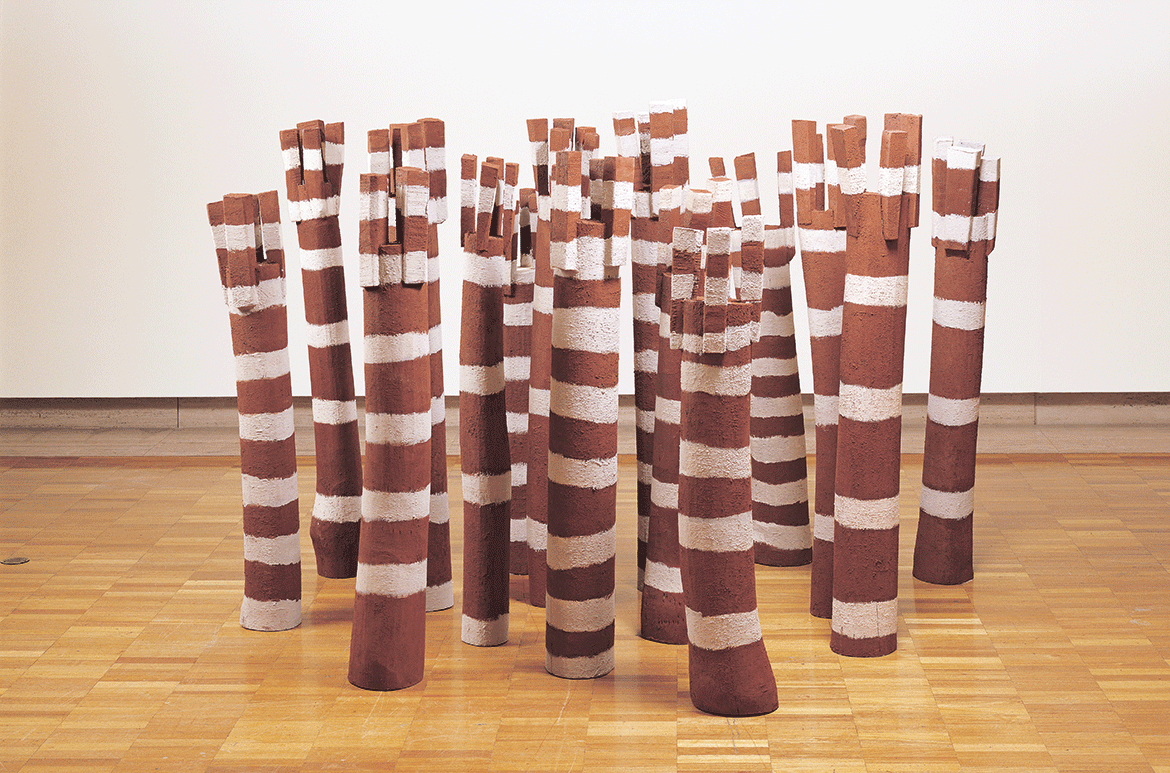

The Thuuth thaa’ munth (law poles) 2002–03 by Wik-Ngathan Elder and custodian Ron Yunkaporta (b.1956) hold potent significance. Traditionally created to be part of a mortuary ceremony, the poles’ white ochre dotting on a red ochre background represents the shimmer of water, referencing the ceremonial body designs of the Apelech people (‘Apelech’ meaning ‘clear water’ in the Wik-Mungkan language).

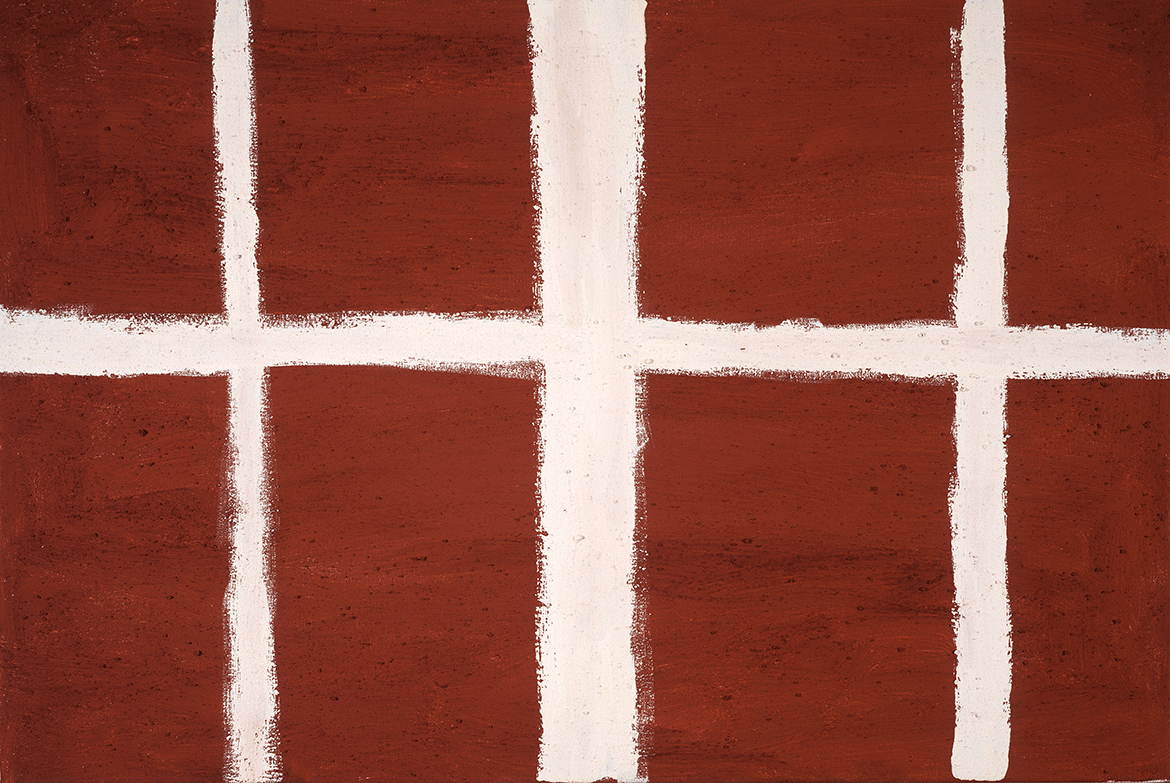

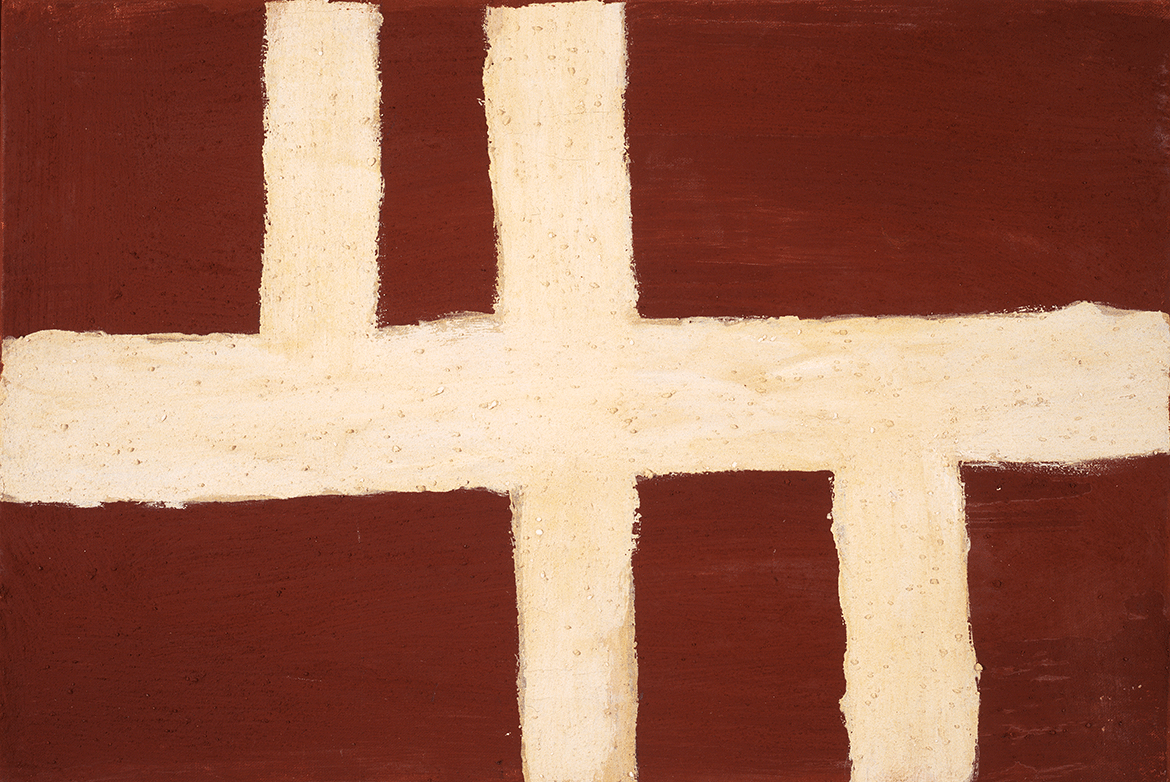

Joe Ngallametta (1945–2005), a Kugu Elder and custodian for the Wanam ceremonial group, was one of the first Wik or Kugu artists to translate their ceremonial painting traditions onto canvas. These early works imbue a powerful, raw quality through the thick application of ochre and white overlay of ceremonial designs still used today. Known as ‘the professor’ throughout northern Queensland, Joe Ngallametta was a performer and senior law man who was head singer for songs about Kang’khan (Sea Eagle) and the Kang’khan Brothers. Kang’khan brother: face 2004 is a simple yet bold abstracted translation of the painting design used by the Kang’khan Brothers to paint their faces whereas Kang’khan brother: face and body painting 2004 is a literal transcription of the face painting of the creator ancestors.

In each, a face is clearly recognisable where the artist paints a central line running along the nose and two lines either side to signify the markings on the outsides of each eye. Thap yongk (Law pole) 2004 and Pole design 2004, are abstracted designs representing the poles made by the most senior law men of the Kugu people.

Joe Ngallametta was also an accomplished carver. Though he only began carving late in life, he became the chief maker of the Thap Yongk, which symbolise ceremonial and ancestral knowledge held in trust for new generations. Thap yongk (Law poles) 2002–03 represents upturned trees, the poles extend from the ground, suggesting branches hidden beneath the earth, while the roots are at the top of the poles, drawing the spirits and returning them to the earth. These poles are an important part of Wanam law and a significant element of ceremony, song and dance for Ngallametta’s people.

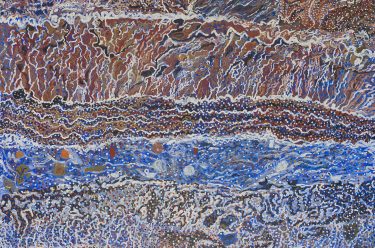

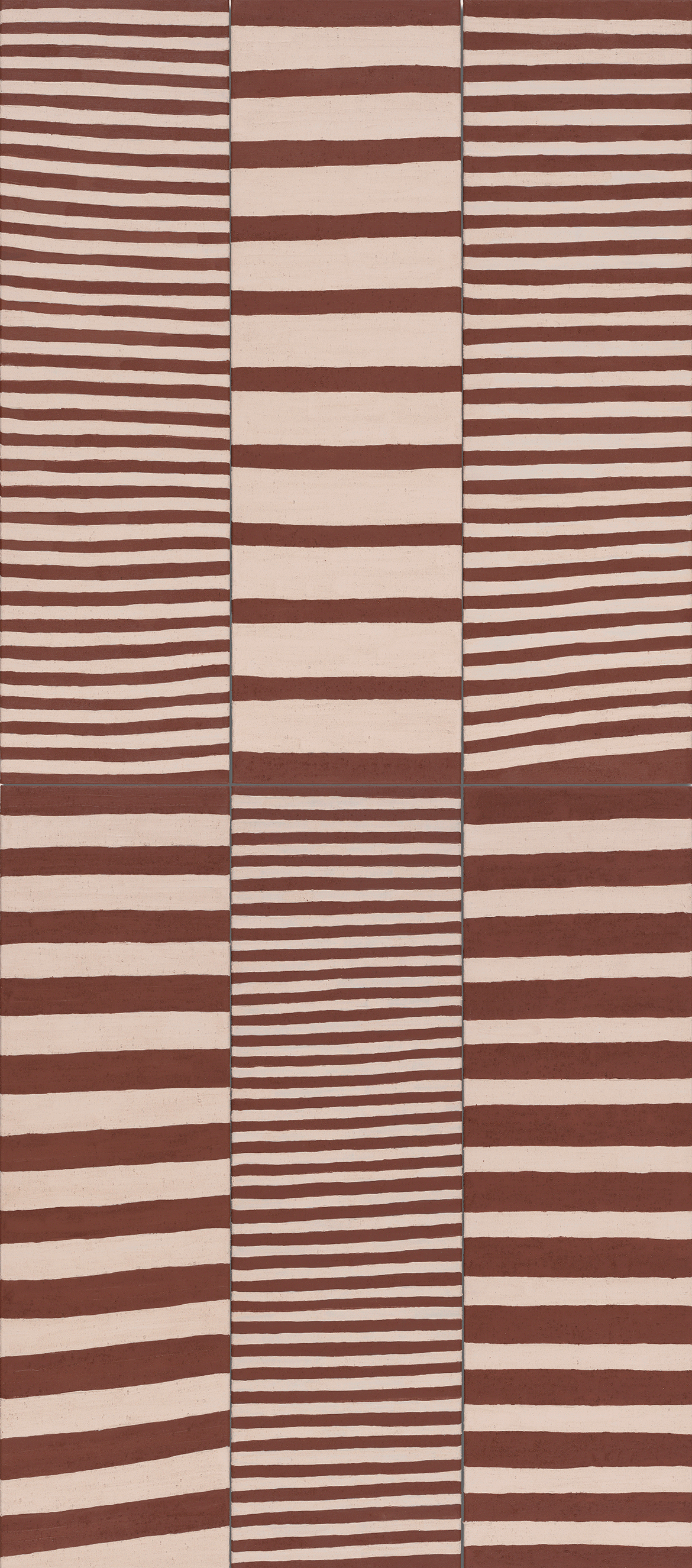

Kugu-Muminh/Kugu-Uwanh leader Joel Ngallametta (1966–2019) inherited significant cultural knowledge from his father, Joe, along with the right to reproduce and reinterpret the customary sculptures and designs of his father’s Kugu clans. Each panel of his sixpanel work Thap Yonk 4 2018 shows a slight variation on the Wanam clan body-painting design, featuring bold alternating bands of red brown ochre and white clay — the same design seen on the Thap Yonk poles — the repetition of these designs onto the painted surface reiterates their enduring importance for Kugu people. According to Joel, the red ochre represents the reflection of the sun as it sets over the Gulf of Carpentaria, the white the reflecting salt water of the shore.1

Similarly, Kalben (A Sacred Site in the Flying-Fox Story) and Walkaln-Aw (Bonefish Story Place) 2008-09 is an intergenerational collaboration between Wik-Mungkan artists Alair Pambegan (b.1966) and his late father, Arthur Koo’ekka Pambegan Jr (1936–2010), a revered law man and Elder. As custodians for the Winchanam ancestral storyplaces of Walkaln-Aw and Kalben, the artists inherited the rights and responsibilities for their associated stories. The left half of the sculpture represents the Flying Fox Story from Kalben. Based on the journey of two young male initiates, it imparts an enduring reminder to Wik-Mungkan people of the importance of observing cultural law and protocol. The right half symbolises the Bonefish Story from Walkaln-Aw, in which two brothers journey from the tip of Cape York in search of a place to call home, only to meet a tragic end and transform into bonefish. The work brings

together two significant Winchanam ancestral stories, reaffirming the multilayered cultural connections of these artists and the ongoing importance of intergenerational artistic and ceremonial collaboration.

Sophia Sambono is Associate Curator, Indigenous Australian Art, QAGOMA

This is an expanded version of an article originally published in the QAGOMA Members’ magazine, Artlines, no.1, 2021

Endnote

1 Joel Ngallametta: Saltwater, Creative Cowboy Films, https://www.creativecowboyfilms.com/blog_posts/joel-ngallametta-saltwater, accessed 23 November 2020.

Acknowledgment of Country

The Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the land on which the Gallery stands in Brisbane. We pay respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders past and present and, in the spirit of reconciliation, acknowledge the immense creative contribution First Australians make to the art and culture of this country.

It is customary in many Indigenous communities not to mention the name of the deceased. All such mentions and artworks are with permission, however, care and discretion should be exercised.

Featured image detail: Ron Yunkaporta Thuuth thaa’ munth (Law poles) 2002-03

#QAGOMA