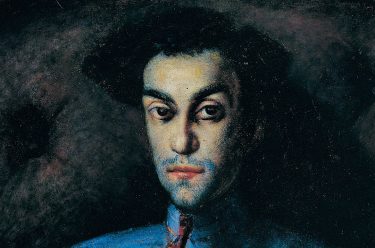

We take a look at William Dobell’s The Cypriot 1940 (illustrated), a portrait of his friend Aegus Gabrielides which is a strange and complex painting with an equally intriguing history. The Gallery’s painting is the last of six known portraits of Gabrielides by Dobell (1899-1970) over a period of several years.

RELATED: The life and art of William Dobell

In general Dobell is best known for lively and apparently spontaneous paintings, either small, rapid, sketch-like studies or larger bravura portraits. In The Cypriot, however, the outcome of so much preparatory study is not a finished portrait done with the well-rehearsed but brisk confidence of a first sketch; this is a painting in which every detail of the composition and nuance of the sitter’s character is minutely considered. The gradual evolution of the image into the intense final portrait may reflect the changing circumstances of the relationship between the two men, as well as the developing aspirations of the artist to create a portrait of enduring psychological power.

Dobell first painted Gabrielides in 1934. In this early version, the sitter meets the viewer’s gaze in an open way, hands on his hips, giving the portrait a slightly cheeky air. This reasonably straightforward recording of the man’s features was to culminate, six years later, in one of the most penetrating individual studies in Australian art.

The strength of Dobell’s best portraits lies in his determination to understand and, if necessary, to exaggerate details of the sitters’ appearance which distinguish them as individuals. It was this aspect of his art which, in the celebrated court case over his Archibald prize-winning Portrait of an artist (Joshua Smith) (private collection) in 1943, caused him to be branded a caricaturist. The brooding image of The Cypriot, however, is anything but a caricature. It is a severe, hieratic portrait which reveals more directly than any of his other works how much Dobell gained from the observation of old master paintings. It marks an important transitional point in the development of his technique from the relative sharpness and clarity of the more thickly worked, coarse-grained London paintings of the 1930s, in which paint was applied almost directly from the tube, to the feathery surfaces that came to distinguish his later work in Australia.

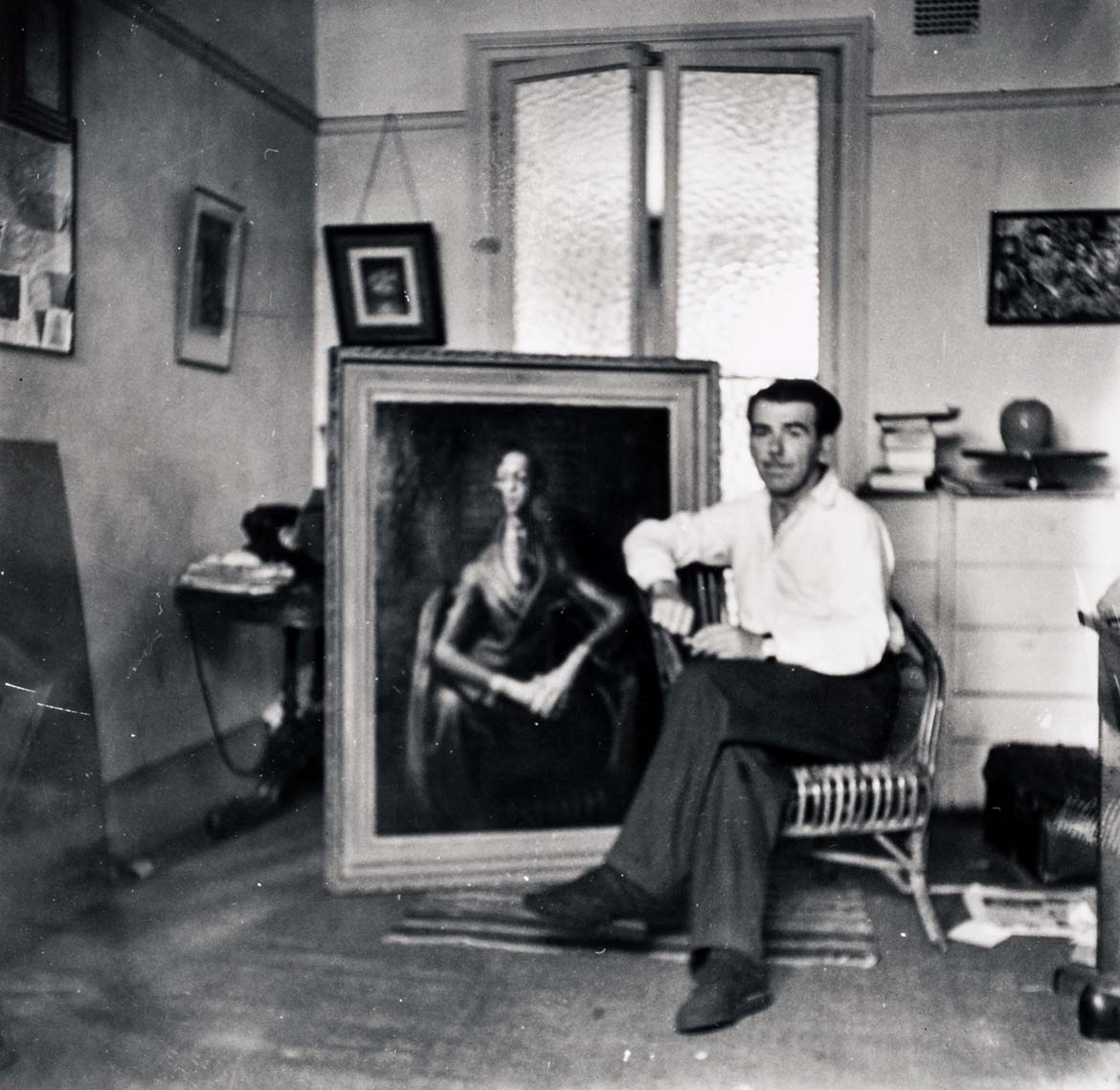

William Dobell in his studio

Dobell admitted that his art was generally rather at odds with twentieth-century Modernism. However, in The Cypriot it is possible to find, in embryo, the personal mannerisms of strong colour, the flurry of light brushstrokes and the bodily distortions (qualities he brought to his art from preparatory studies) with which Dobell would strive to make his work progressive.

All the studies for The Cypriot were made in London, presumably from the sitter. Back in Sydney, away from Gabrielides, this image of the man in a chair, impressed on Dobell’s memory from repeated depictions, could be manipulated according to his imagination. Dobell’s progress towards the final portrait is particularly well recorded in the preliminary versions he brought home from London. They allow us to see the finished picture taking shape and offer a glimpse into the artist’s private laboratory.

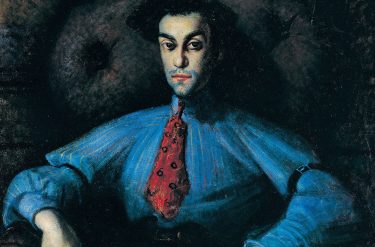

The starting point is a classically stable triangular composition, with the sitter placed symmetrically and looking directly at the viewer with a rather matter-of-fact expression, seated in a tall, button-tufted Victorian armchair. The chair-back rises above his head beyond the picture-frame. The transformation of the subject from a familiar waiter to a glamorous courtier was achieved through fairly subtle modifications. The upholstered chair was evidently of the rococo-revival design, its back topped with a circular curve that made a halo shape around the head of its occupant. This is how it appears in the first, 1934, version. In the final portrait, the pyramidal composition is destabilised by emphasising the vigorous outward thrust of the man’s bent elbows and repeating it in other details. The sitter seems taller, and he occupies the chair with greater authority. The shape of his hair is made to rhyme with the shape of the chair-back and the angles of his elbows. This exaggerated side-to-side lunge is charted like a seismographic movement by the pattern on his tie, and the jagged lines are combined with circles to create a frenetically unsettling design (although the gaudy, wide neckties of the 1940s make this detail plausible).

The strong outward movement of drapery folds and stripes in the shirt is interrupted and made more complex by buckled armbands, making the garment slightly reminiscent of a Renaissance doublet. The hands, which were originally placed at the same level, are enlarged and positioned asymmetrically, so that the hand on the right is advanced forward, is larger and lower, and hangs above the bottom edge of the painting like a claw. Dobell increased the arch of the sitter’s brows and deepened the shadows around his eyes. The fixed gaze and haughty pose seem rigidly frozen, yet the composition generates a force that pushes outward from the frame. The acanthus spirals, which spin like Catherine wheels on the ends of the chair’s arms, are a dramatically amplified variation on the relatively demure neo-rococo tendrils copied from the actual chair in earlier versions. These whorls of paint, and the urgently scribbled lines running down the necktie, are abstracted from the real motif.

William Dobell ‘The Cypriot’

El Greco ‘Portrait of the Grand Inquisitor Don Fernando Niño de Guevara’

Appropriately for the ‘Greek’ subject, the single greatest influence on this painting seems to have been the Renaissance artist El Greco, whose work provided a prototype for the highly charged variant on the classical formula of triangular portrait composition. The Cypriot is very similar to El Greco’s glowering portrait of the head of the Spanish Inquisition, Portrait of the Grand Inquisitor Don Fernando Niño de Guevara (The Metropolitan Museum of Art), painted in Toledo, Spain, in about 1600, a suitable subject for Dobell to use as a model for his darkly evocative character study. El Greco’s Portrait of Fray Hortensio Felix Paravicino c.1610 (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) would have been another obvious stylistic source for The Cypriot.

Of course, The Cypriot is also a picture of someone who seemed to Dobell to be interesting and perhaps attractive because of his foreignness. Gabrielides may have represented a kind of exoticism to Dobell. When he painted the final portrait back in Sydney, where Southern European faces were uncommon before postwar immigration, The Cypriot evoked a distant cosmopolitan world left behind in London, the world of great museums and old master paintings that had sustained the young artist.

As well as the paintings and drawings that have approximately the same composition as The Cypriot, in 1936 Dobell painted a picture of Gabrielides known as The Sleeping Greek (The Art Gallery of New South Wales). In this painting of the man’s head in extreme close-up with the brown upholstered chair as a background, Dobell captured him completely unaware, like a wild animal in repose. Dobell’s fascination with this natural sensuality is a recurring aspect of the small, brilliant character studies he made of other London personalities.

It is very possible that Dobell and Gabrielides were lovers. No other individual sat so often for Dobell, in the intimacy of his flat, over such a long period (at least four years). The closeness of their friendship is evident from the fact that Dobell was asked to be one of seven best men at the Greek Orthodox wedding of Gabrielides. In fact, Dobell went to the ceremony but did not participate, instead sitting at the back of the church, and knowingly or otherwise casting an inauspicious omen over the marriage by destroying the important numerical composition of the rites. Soon after this he returned to Australia. The exact nature of their relationship, and how Dobell regarded Gabrielides when finally he painted him from memory, can only be a matter for speculation. Much later, during an interview in the early 1960s, Dobell characterised his leading sitter as ‘dignified’, but also as a ‘coward’.

Despite being so well documented, The Cypriot remains an enigma. It is a completely uncharacteristic, even somewhat bizarre work. The sitter’s ambiguous expression is ultimately indecipherable. This is, of course, one of the reasons why it is such a successful portrait.

Extract from Timothy Morrell’s essay ‘Dobell and Modern Mannerism’ published in Brought to Light: Australian Art 1850-1965, Queensland Art Gallery, 1998.

Art conservation

Go behind-the-scenes with Anne Carter, QAGOMA Conservator, Paintings and watch as she delves into the secrets once hidden behind The Cypriot. There is a lot more to the painting than meets the eye — all hidden from view under the surface — until the painting was x-rayed.

Featured image detail: William Dobell The Cypriot 1940

#QAGOMA