A new exhibition of Indigenous art takes movement, both literal and figurative, as its theme, inspired by the well-known song of the same name, ‘Get Up, Stand Up’ features ceramics, sculpture, etchings, photography and painting by artists across Queensland whose works are underpinned by the desire for engagement and justice.

‘It’s not all that glitters is gold, half the story has never been told,

So now you see the light, stand up for your rights

Get up, stand up, stand up for your rights,

Get up, stand up, don’t give up the fight1’

Recorded in 1973, the song ‘Get up, stand up’ by visionary Rastafarian musicians Bob Marley and The Wailers has long been synonymous with social resistance movements globally, including those within Indigenous Australia. Growing up in Jamaica in the 1950s and 60s, Marley was part of the black African diaspora, ‘that population throughout the world that had been scattered or colonized as the result of the slave trade and imperialism’.2 In the 1970s, recognising their commonalities, and at a time when Indigenous community services were being established across the country, many social movements in Australia adopted Marley’s reggae anthems as their own. His music and its themes of social justice lent a voice to the unheard and mobilised likeminded people searching for change.

Similarly, the works in ‘Get Up, Stand Up’ express their makers’ engagement with Indigenous cultural, familial and political movements. From depicting literal movements of the body — in dance and in protest — to figurative explorations of historical movements and events, this Collection exhibition focuses on the works of Indigenous Queensland artists who assert their sovereignty and seek political and social equality; an ongoing struggle that has gained a renewed sense of urgency with the Black Lives Matter movement.

Freedom of movement

In the latter half of the nineteenth century, Indigenous people’s freedom of movement was severely restricted: communities were forcibly moved from their traditional lands to the reserves and missions created by the governments of the day; and children were removed from their families,3 in an attempt to break ancient lines of cultural knowledge and practices. Here, a group of contemporary paintings by Lardil artists Joelene Roughsey, Wunun Wayne Williams and Gordon Watt show ceremonial body markings and dancewear, celebrating their freedom to practise culture and symbolic of their ancestors’ free movement across the land. The freedom to dance and conduct ceremonies is further highlighted in ceramic works by Naomi Hobson, Lawrence Omeenyo and Janet Fieldhouse. Finally, as the name suggests, Patrick Thaiday’s Zugub (Dance Machines) 2011 are articulated sculptural objects activated by dancers during performances — the most literal embodiment of the theme.

Naomi Hobson ‘Malkarti Poles (Dancing Poles)’

Janet Fieldhouse ‘Dance series: Transformation 4’

porcelain / Four parts: 18.5 x 4.5cm (diam.); 6 x 34.5 x 6.5cm; 9 x 32 x 10cm; 25.5 x 5.5cm (diam.); 18 x 32 x 36cm (installed) / Purchased 2009 with funds from the Bequest of Grace Davies and Nell Davies through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Janet Fieldhouse

Patrick Thaiday ‘Zugub (Dance machines)’

Interruption of movement

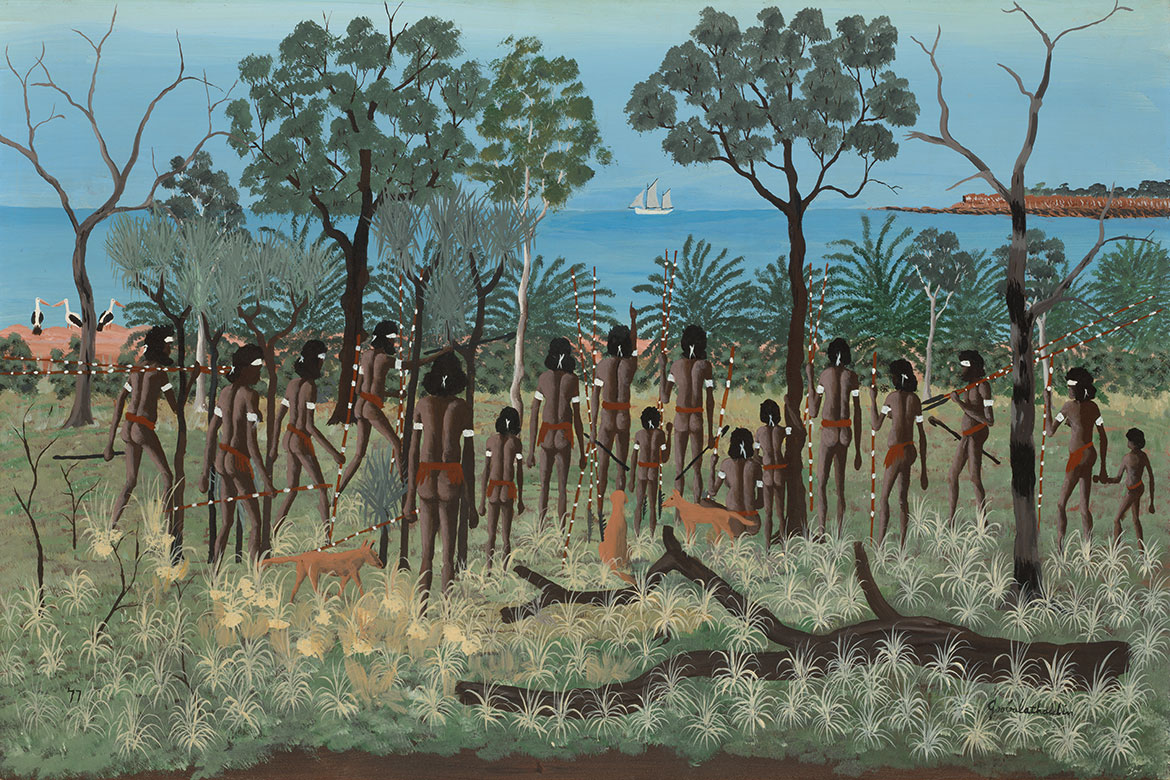

The exhibition includes works that point to the frontier era of Australian history and depict restrictions on freedom, but which also acknowledge the introduction of new artistic aesthetics. Based on his Elders’ early experiences, Goobalathaldin Dick Roughsey’s illustrative history paintings offer glimpses of first contact with Europeans in the northern Cape. Vincent Serico’s Carnarvon collision (Big map) 2006 shares an important historical narrative, including both pleasantries and hostilities. And while Serico uses oral accounts of colonisation from his family and community to create new visual narratives, Danie Mellor takes advantage of existing colonial photography of his ancestors and their rainforest home, shown here in a blue palette inspired by the decoration on English Spode ware. Dale Harding’s abstract ochre painting We breathe together 2017 incorporates natural pigment from his ancestral region, Carnarvon Gorge, interrupted by a field of Rickett’s Blue laundry whitener, once a highly prized and traded item on the frontier, and for Harding, symbolic of the domestic labour that generations of his female ancestors were forced into under government policy.4

RELATED: Read more about Danie Mellor’s ‘The pleasure and vexation of history’

RELATED: Delve into the work of Goobalathaldin Dick Roughsey

Goobalathaldin Dick Roughsey ‘First Missionary, Mornington Island’

Vincent Serico ‘Carnarvon collision (Big map)’

Danie Mellor ‘The pleasure and vexation of history’

Involuntary movement

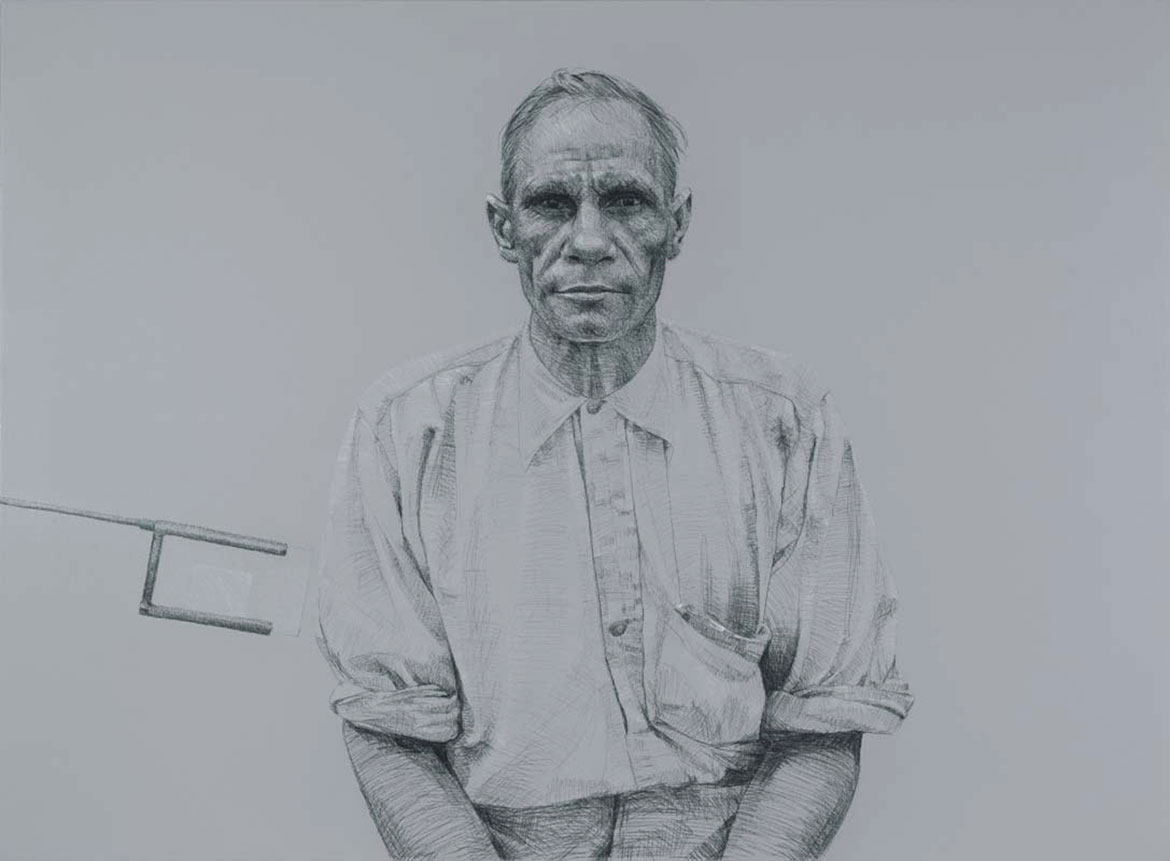

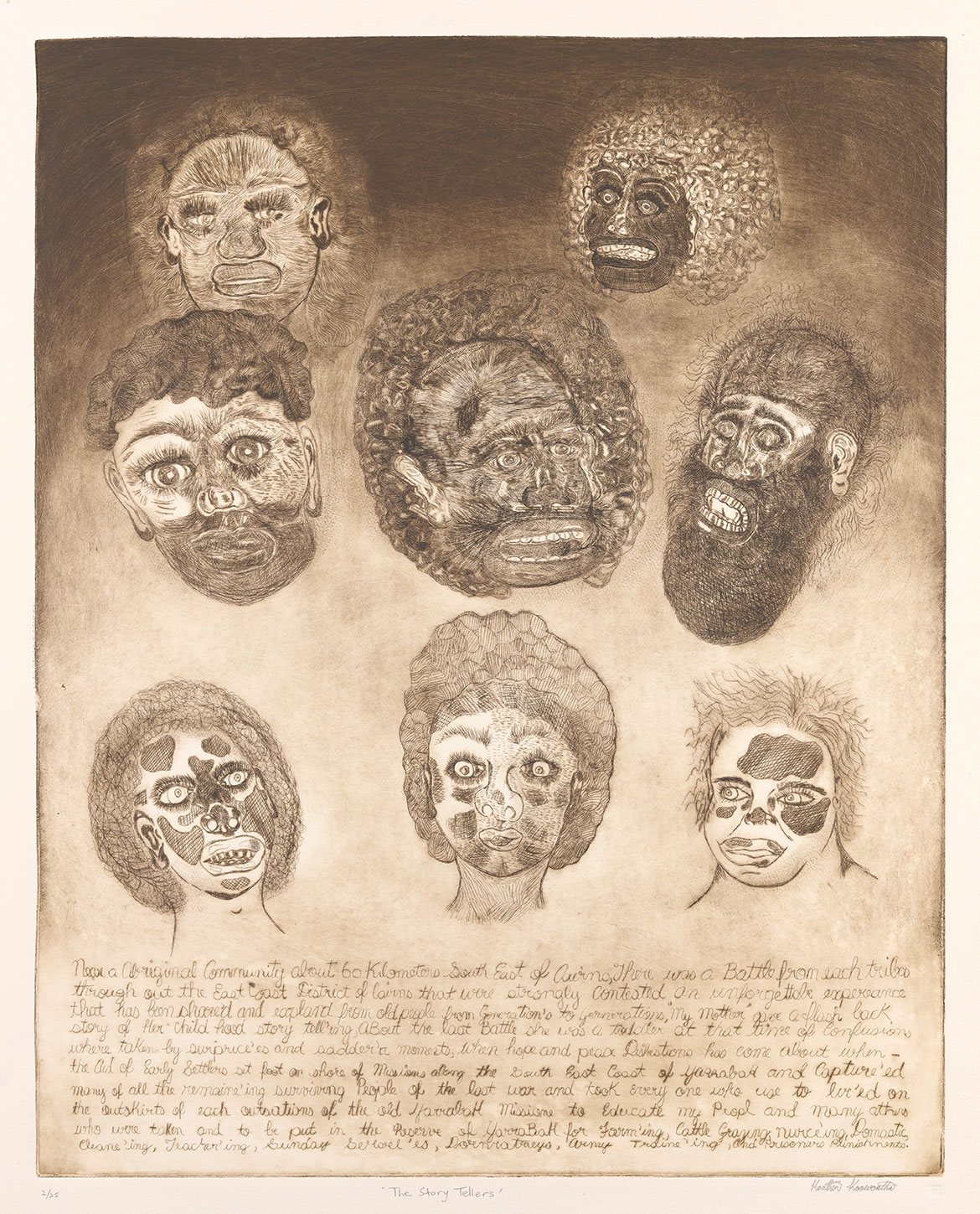

Reflecting their families’ experiences of involuntary movement off Country, away from family and onto missions and reserves, as per the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of Sale of Opium Act 1897, personal portraits by Vernon Ah Kee and Heather (Wunjarra) Koowootha expose the Act’s ongoing effects on community. The introduction of Christianity is a common thread in works by Archie Moore and Cornelius Richards, presenting complex perspectives on its arrival, which provided both sanctuary and oppression. Richards spent many years working with the Yarrabah Guyala Pottery from the 1980s onwards: as with Yarrabah, many other missions opened commercial operations involving art and craft. Artist Mervyn Riley also created works at the Barambah Pottery that are typical of the 1970s era. Due to their production-line manufacture, however, many objects produced at Barambah (now known as Cherbourg) lack artists’ inscriptions and instead credit ‘Cherbourg artists’ with their creation.

Vernon Ah Kee ‘neither pride nor courage’

Heather Marie (Wunjarra) Koowootha ‘The story tellers’

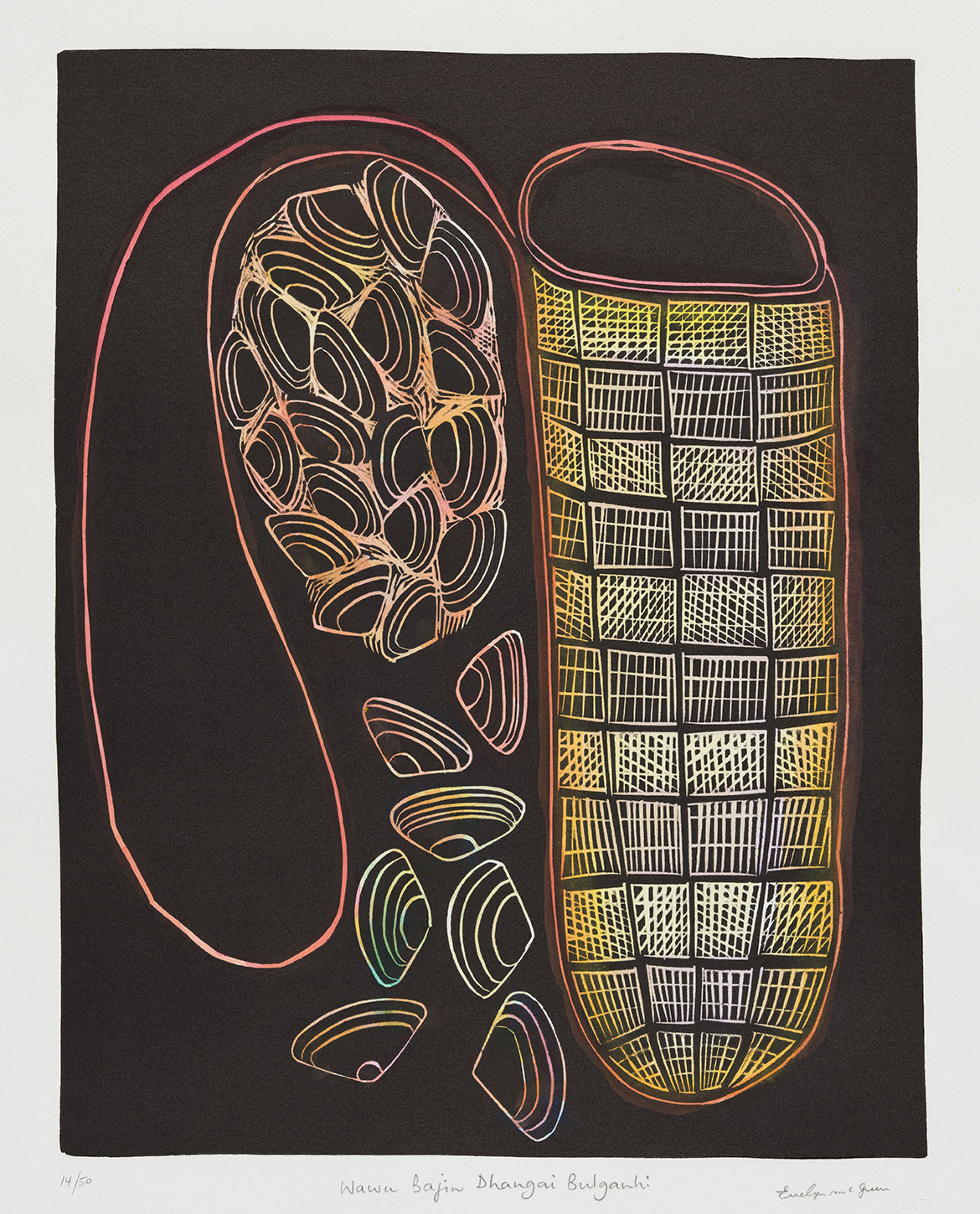

A series of fibre works demonstrates the diversity of materials and techniques in Queensland fibre art practices, specifically bag-making. The rotating selection of works includes traditional forms and stitching, styles taught by missionaries, and contemporary experimentation. Examples range from Abe Muriata’s rainforest Jawun (bicornial baskets) to Jenny Mye and daughter-in-law Charlotte Mye’s polypropylene tape bags (used in place of customary coconut leaves); from Clara, Margaret, Doreen and Mynor Yam’s string bags associated with their home, Kowanyama, to Philomena Yeatman and Ruby Ludwick’s coiled palm-fibre works — a technique introduced to the regions; to Wilma Walker and Dorothy Short’s kakan and puunya (baskets), created from materials and techniques unique to their ancestors. These are complimented by Evelyn McGreen’s portfolio of prints, depicting the multitude of functions for a variety of basket shapes.

Evelyn McGreen ‘Wawu bajin dhangay bulganghi (Strainer for washing clams and shellfish)’

Providing a darkly humorous conclusion to the group is Sue Elliott’s painting Christ I’m tired c.1993, which features the crisp use of the colloquialism with the concentric dotted circle now synonymous with ‘Aboriginal Art’. Significantly, the early mission franchises encouraged artists to use dominant stylistic devices like dot-painting in their works, instead of more individual techniques, in order to raise revenue.

Defiant movement

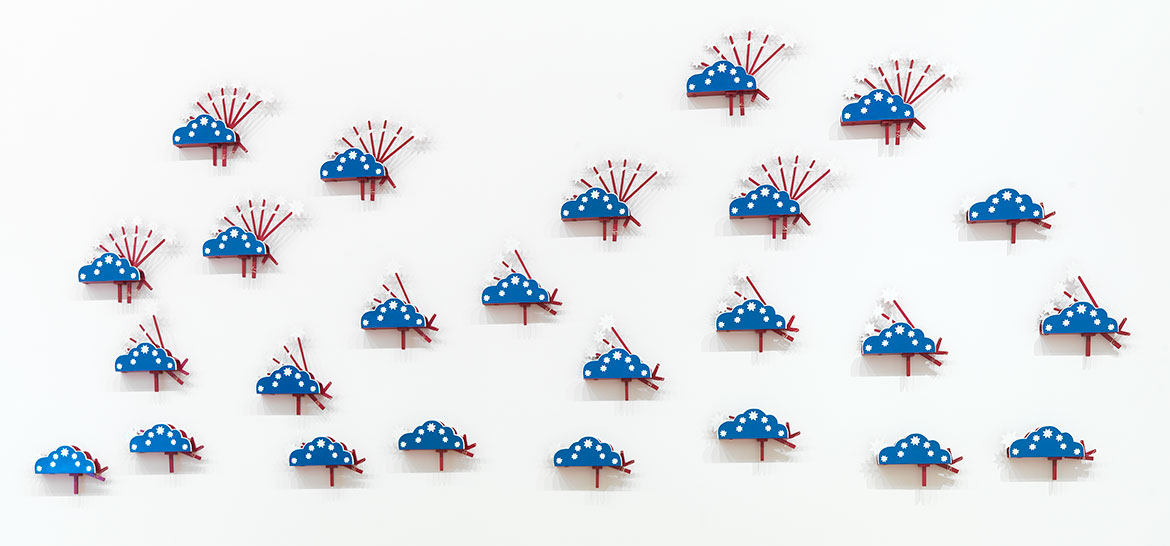

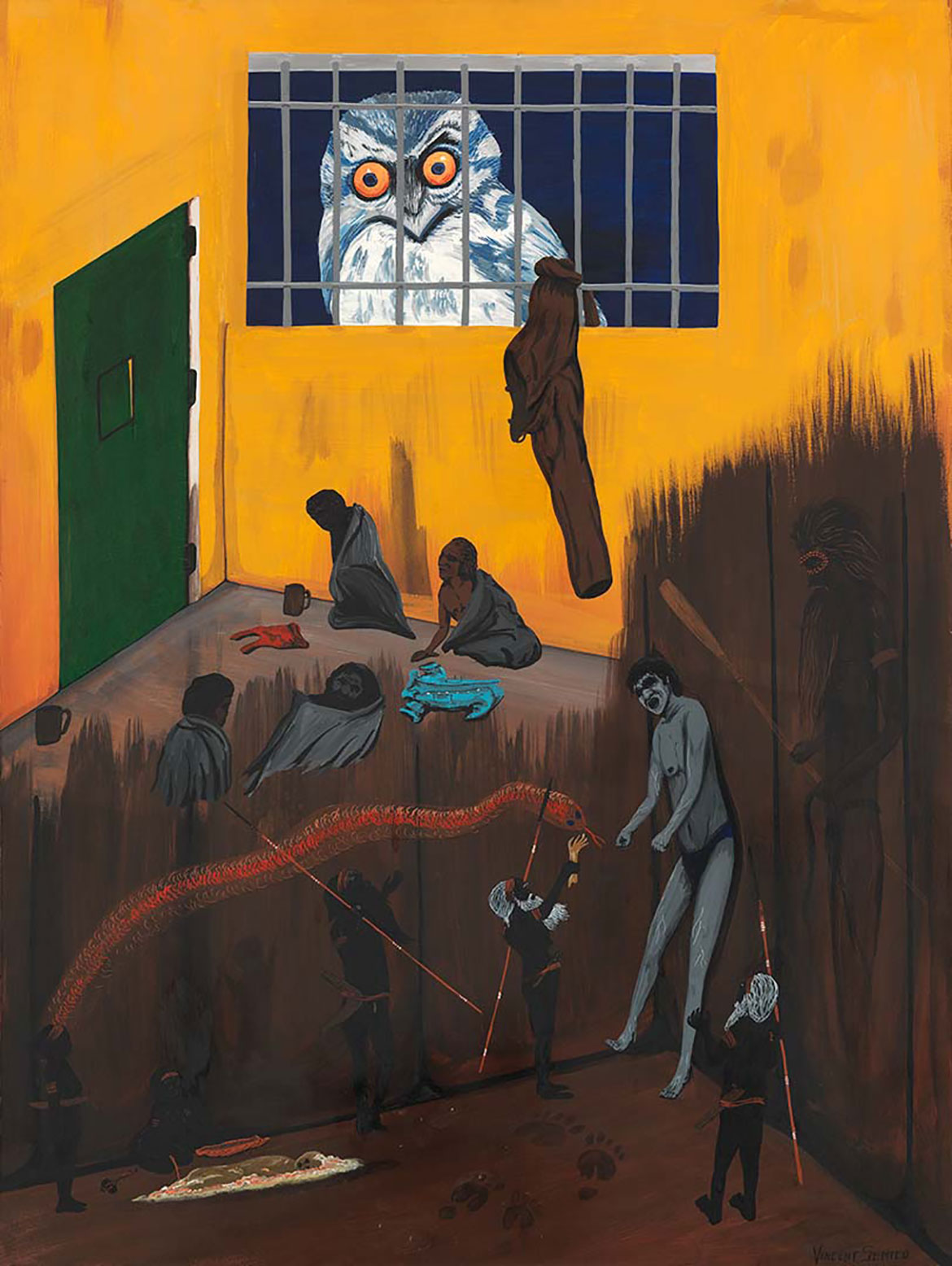

Protest takes hold in Richard Bell’s Prospectus.22 1992–2009, in which he seeks to trade British colonial rule — due to there being no treaty in place — with the People’s Republic of China. The overtly political works of Gordon Hookey and Vincent Serico — Wreckonin 2007 and Deaths in custody 1993, respectively — graphically present content relating to the deaths of Indigenous people in legal custody. Deliberately provocative and inflammatory, Hookey’s work responds to what he sees as Australian society’s silence on the subject of Aboriginal justice and the system’s lack of accountability; while the central figure in Serico’s painting suffers the punishments of both traditional beliefs and white man’s justice, trapped not just by a cell but by inescapable despair.

Gordon Hookey ‘Wreckonin’

Vincent Serico ‘Deaths in custody’

Revered movement

Numerous works in ‘Get Up, Stand Up’ honour hard-won achievements — the freedom to play sport, to connect or reunite with family — and celebrate the actions of those whose sacrifices paved the way ahead. Aboriginal fast-bowler Eddie Gilbert was Ron Hurley’s childhood hero and is immortalised in Hurley’s Bradman bowled Gilbert 1989. While Gilbert was an exceptionally skilled cricketer, it was Bradman who would go on to be knighted and become a household name. With this work, Hurley comments on the difference in the lives of these two equally talented men.

RELATED: Read more about Shirley Macnamara’s ‘Skullcap’

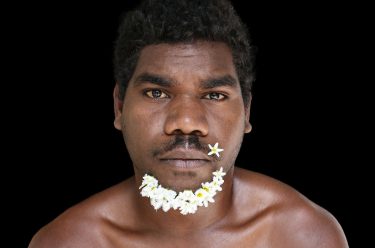

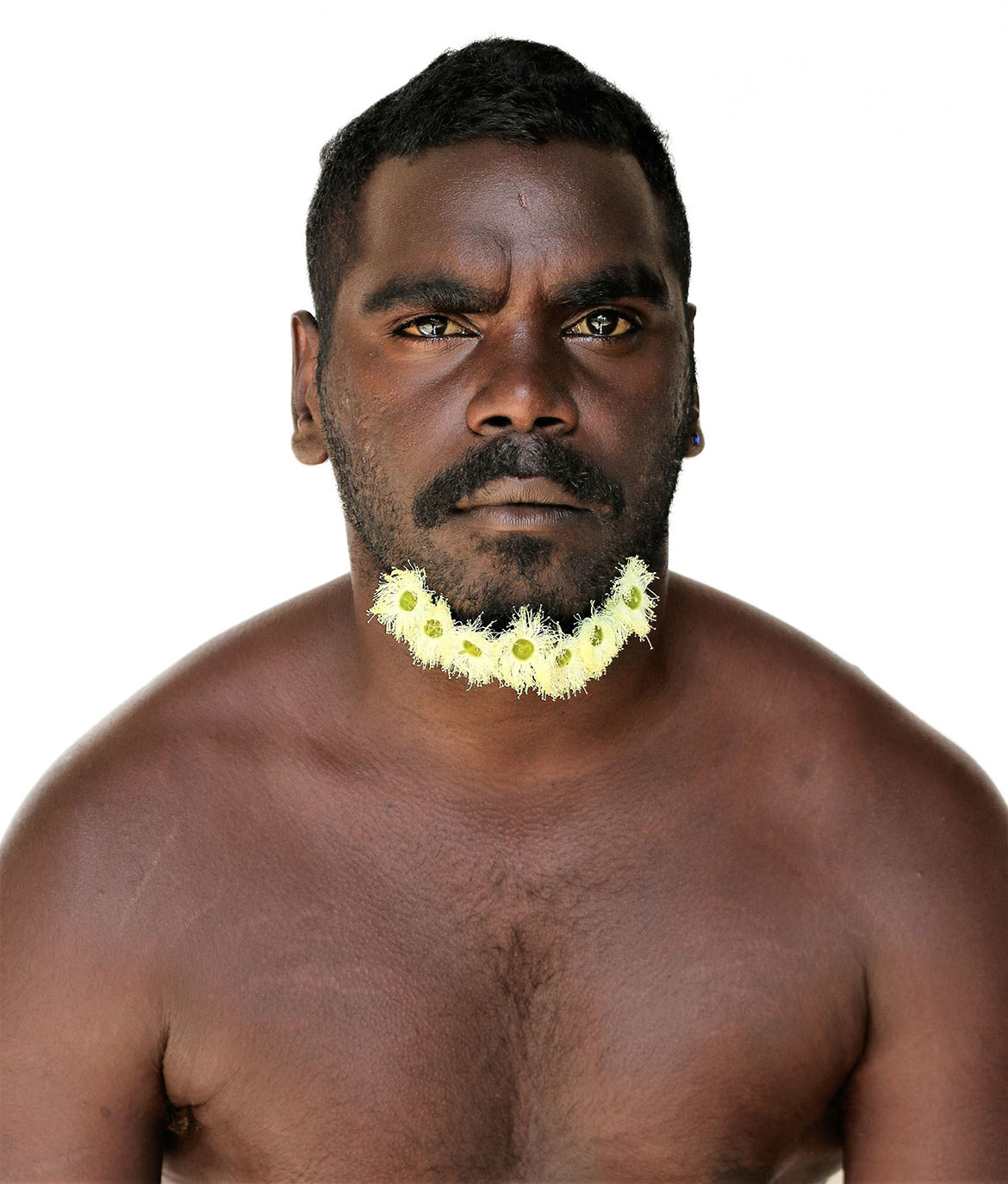

On a more sombre note, Shirley Macnamara’s Skullcap 2013 is a memorial to the many thousands of Aboriginal soldiers who have fought for their communities and Country — locally, nationally and internationally, and in wars throughout history both written and unwritten. Naomi Hobson’s ‘A Warrior without a Weapon’ series of 2018 also highlights the role of Aboriginal men, and pictures men and boys from the artist’s hometown of Coen and nearby Lockhart River adorned with flowers — a traditional decoration. The series aims to counteract the overwhelmingly negative contemporary portrayal of Indigenous men in Australian media, with Hobson having witnessed the harm such representations can cause, and instead shows their nurturing and compassionate qualities.

Engaged with Australian social movements both literal and figurative, ‘Get Up, Stand Up’ presents elegant ceramics, sculptural works, figurative etchings, portrait photographs and paintings by Indigenous artists from across Queensland, and illustrates the ongoing impact of the country’s modern history on Australia’s Indigenous peoples.

Katina Davidson is Acting Curator, Indigenous Australian Art, QAGOMA

Endnotes

1 Lyrics from ‘Get up, stand up’, penned by Bob Marley and Peter Tosh, 1973.

2 Mikal Gilmore, ‘The life and times of Bob Marley: How he changed the world’, Rolling Stone, 10 March 2005, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/the-life-and-times-of-bob-marley-78392/, viewed 20 September 2020.

3 See John Gardiner-Garden, ‘From Dispossession to Reconciliation’ [Research Paper 27, 1998–99], Social Policy Group, Parliament of Australia, 29 June 1999, https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp9899/99Rp27#nineteenth, viewed 13 October 2020.

4 See Ella Archibald-Binge, ‘New exhibition re-examines Australian history through art’, NITV, SBS, 3 October 2017, https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/nitv-news/article/2017/09/29/new-exhibition-reexamines-australian-history-through-art, viewed 14 October 2020.

Ron Hurley ‘Bradman bowled Gilbert’

Shirley Macnamara ‘Skullcap’

Naomi Hobson ‘A Warrior without a Weapon 3’

‘Get Up, Stand Up’ / Queensland Art Gallery / 19 December 2020 until 20 November 2022

Acknowledgment of Country

The Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land upon which the Gallery stands in Brisbane. We pay respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander elders past and present and, in the spirit of reconciliation, acknowledge the immense creative contribution Indigenous people make to the art and culture of this country.

It is customary in many Indigenous communities not to mention the name of the deceased. All such mentions and photographs on the QAGOMA Blog are with permission, however, care and discretion should be exercised.

Featured image detail: Naomi Hobson A Warrior without a Weapon 3 2018

#QAGOMA