In 1957, artist James Gleeson, then art critic at The Sun newspaper, wrote that the paintings of Ian Fairweather (1891-1974) would never last.1 Reputedly using whatever materials came to hand within his itinerant lifestyle, the paintings of Fairweather are renowned as much for their fragility as their beauty, and this is part of their appeal.

Fairweather lived and painted on Bribie Island over a period of 21 years from 1953 until his death — he was 60 when he settled in a grass hut in the bush, lit only by hurricane lamps, on the smallest and most northerly of three major sand islands in Moreton Bay, just an hour’s drive from Brisbane.

Ian Fairweather painting in his studio

Materials

From 1958 Fairweather developed his late style using ‘plastic paints’ — in 1963 he recounted that he mostly used powder colour and poly vinyl acetate (PVA)2, however very little has been published on Fairweather’s materials and there is almost no reported medium analysis.

An initial examination of Fairweather’s late works in our collection revealed unstable paint and altered paint surfaces, with many artworks requiring reframing — as was with a previous treatment carried out on Head 1955. In order to plan a conservation approach to treat these paintings the QAGOMA’s Conservation section commenced a study to investigate materials and to develop suitable mounting and framing techniques.

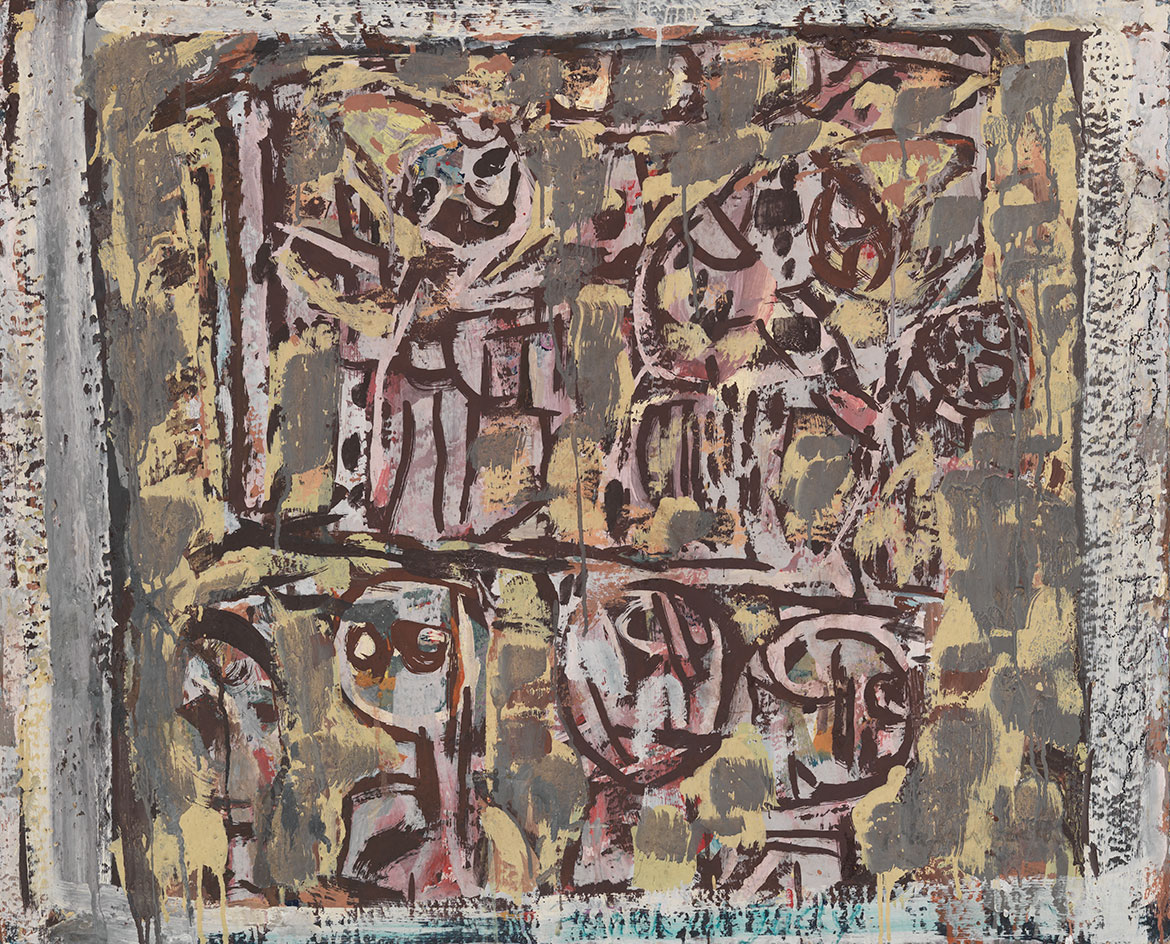

Ian Fairweather ‘Punch and Judy’

Ian Fairweather ‘Alpha’ 1951

RELATED: Ian Fairweather

The story of Fairweather’s material use is long and complex. He formally trained at the Slade School in London, and his early works contain leached oil mediums. He began to avoid using oil paint in the late 1930s due to an allergic reaction. Thus, from 1939, he was looking for water-based matt and bodied paint.3 Suitable commercially available paints at this time would have included artist watercolours and gouache, decorator paints including casein and distemper, and poster colours made from cellulose. — water based synthetic paints were not yet available. War rationing and poverty would have also affected his material choices as interviews and letters describe his use of unusual materials from the 1940s until 1958, for example, soap, casein, Clag Paste and Reckitt’s Blue washing agent are mentioned.4 Paintings from this period are among the most fragile of Fairweather’s oeuvre.

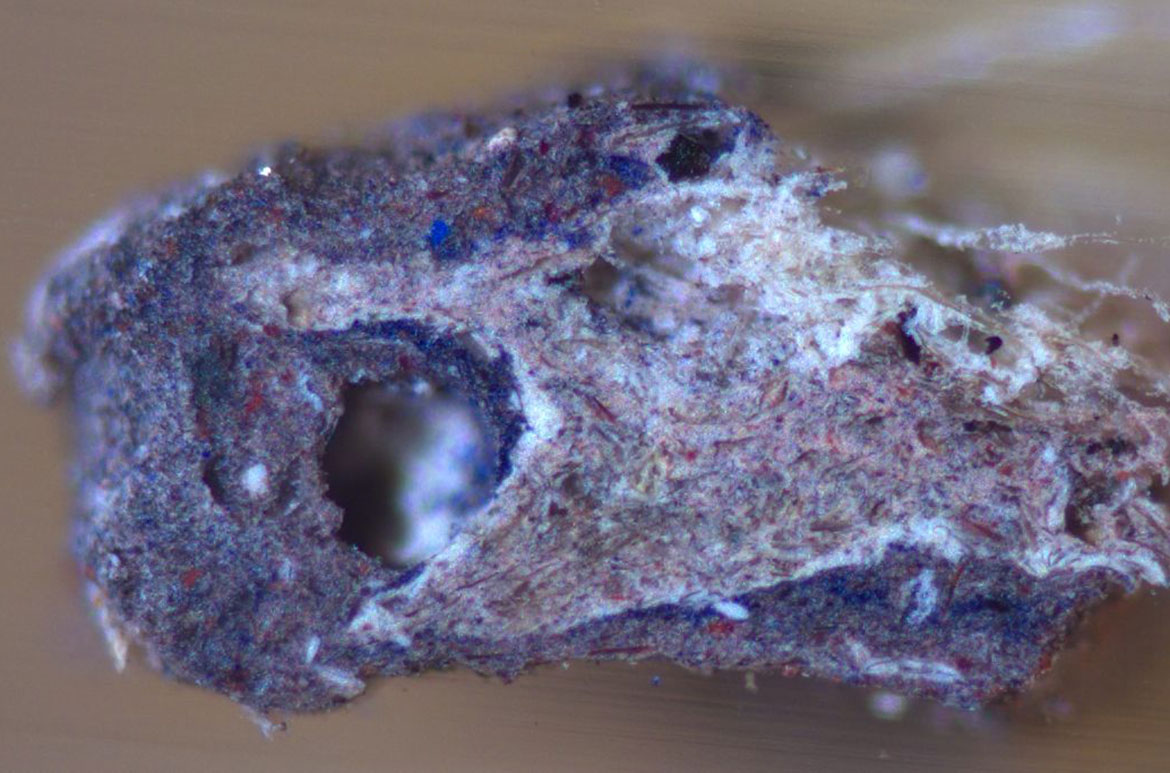

Paint analysis was undertaken through the QAGOMA Centre for Contemporary Art Conservation utilising fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) for initial characterisation, as well as ultraviolet light imaging (UV), infrared red reflectography (IR) and industry research. A material theory that is being investigated is that of Murray Bail who proposed that Fairweather only started painting his late larger paintings from 1958 when water based dispersions were available to him.

Ian Fairweather ‘Bus stop’ 1965

Research to date has revealed the earliest use of synthetic polymer in a painting from 1956, this being an oil modified alkyd paint which is likely to be solvent based. Material analysis supports his predominant use of poly vinyl acetate from 1959, but also revealed his continued use of alkyd as well as a yet uncharacterised paint media. FTIR analysis of media from pre 1956 paintings has proved difficult with samples not identifiable due to the paint being under bound. However, a significant finding is that Fairweather was not exclusively using water based paints at this time.

Ian Fairweather ‘Trotting race’ 1956

Fairweather’s technique continues to elude a simple understanding. He was an artist whose work, including the palette, was directly influenced by the availability of materials. This initial research confirms that the fragility of his paintings varies enormously depending on their date, the support, the type of paint materials used and environmental and conservation history. Even though the late paintings are more robust than works from the 1940s and early 1950s, the way Fairweather used paint, what he added and how he adjusted the medium has not rendered all late paintings inherently stable.

Mounting

Two techniques have been developed to prepare Fairweather’s paintings for display. Both techniques — cradle mounting and sink mounting — have been designed to manage the fragile nature of the artworks.

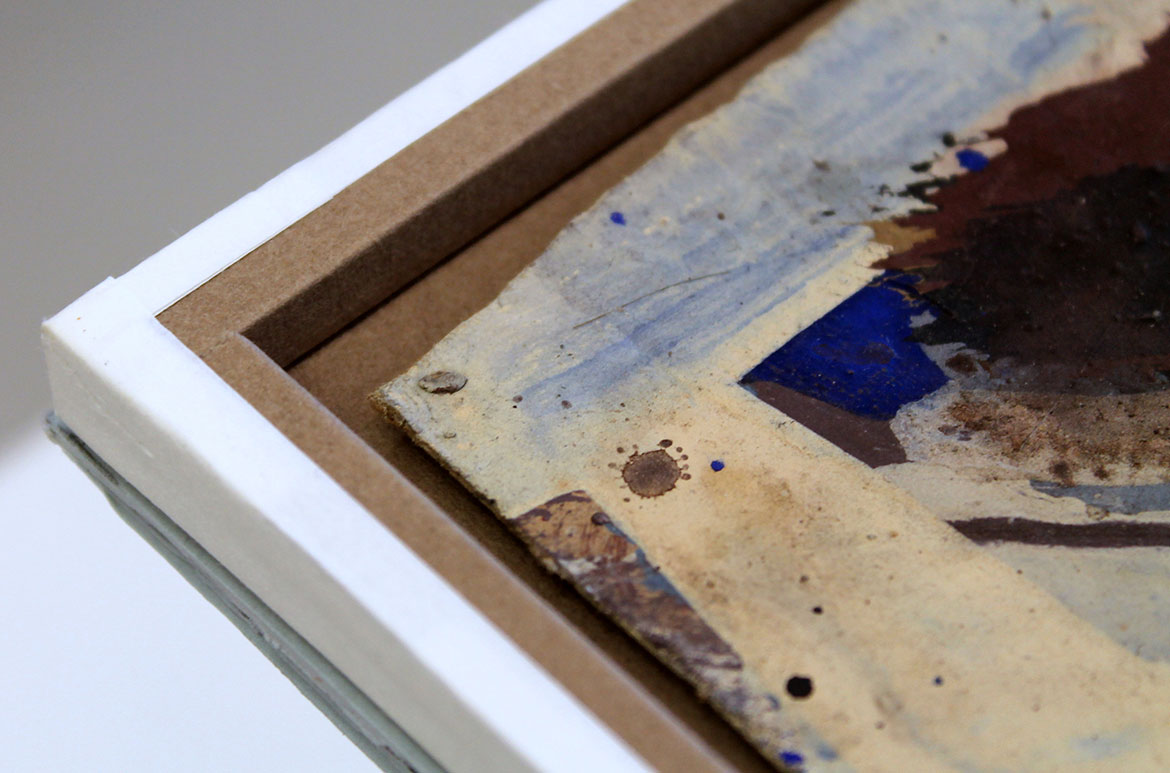

An assessment of our Fairweather paintings revealed that most of the painted surfaces extended to the edges of the supports. Some artworks were also found not square and others with quite irregular edges — interestingly, in numerous paintings the artist has used a painted border as a framing device.

The main objectives that were addressed in developing new mounting techniques were:

- To reduce the impact of the frame on the delicate, vulnerable edges of the paintings

- To ensure that the frame glazing never comes in contact with the paint surface

- To reveal as much of the painted surface as possible, given that the artist frequently painted up to the very edge of the support

- To create a sound working edge for framing

To prepare paintings that have been adhered to Masonite for framing, wooden Western Red Cedar ‘cradles’ were manufactured measuring 1cm larger on all sides than the artworks. The artworks were then carefully attached to the cradles using a Velcro system. When a painting is attached, the cradle acts as a ridged auxiliary support taking the distributed weight and pressure of the frame away from the delicate edges of the painting support and the paint film at the edges.

Ian Fairweather ‘Bus stop’ 1965

Paintings on paper supports, such as cardboard and newspaper that have not been adhered to solid secondary supports are some of the most vulnerable to paint cracking and damage, this is because the paper support responds to changes in humidity and temperature by cockling and bending. The paint layers are not as flexible as the paper support and consequently can crack — these works are also difficult to handle as the paper is flexible and the paint is not.

Preparation of these works for framing required the use of thick acid free cardboard auxiliary supports, attached using Japanese tissue tabs and starch paste. In a similar method to the cradle, the cardboard was larger all the way around the perimeter of the artwork, allowing the cardboard support to take the pressure of the frame. Once tabbed to a cardboard support, the works on paper were fitted with a sink mount. A sink mount is a surrounding edge of cardboard that is high enough to allow for any dimensional changes in the paper, essentially the sink mount acts as a spacer to keep the glazing from touching the paint surface.

Ian Fairweather ‘Trotting race’ 1956

Framing

Fairweather left the choice of selecting picture frames for his paintings to others. Very little information is available in regard to the way in which Fairweather envisaged how his paintings would be framed or displayed. All of his artworks were sent to dealers or galleries unframed thus entrusting the decision of selecting profiles, styles and finishes to a second party. The main sources of information documenting the styles of picture frames used on Fairweather’s paintings exist mainly in exhibition installation photographs, oral records or on paintings in both public and private collections.

The frame styles used on these artworks were contemporary to the period. The picture framing industry of the early to mid-20th century was vastly different to that of the 19th century with the use of gold leaf and carved or applied ornament being replaced with painted finishes, plain mouldings and linen slips. There was a shift towards simplicity of design throughout the 20th century away from earlier heavier styles of the preceding centuries.

Technological advancements in manufacturing techniques and materials influenced architecture, interior design and consequently picture frames. Gold leaf, the traditional finish on picture frames for centuries, was being replaced with other decorative surface finishes such as aluminum and silver leaf, painted and textured finishes, the use of fabrics and natural finishes sealed with polishes or wax, all designed to harmonize with modern interior spaces.

Mid-20th century modern design introduced profiles and shapes to picture frame mouldings that retained some elements of historical framing vernacular while eliminating all forms of applied ornament, thus exposing the frame’s simple structure. Original period frame styles found on artworks by Fairweather epitomize this modern aesthetic, consisting of simple linear mouldings, usually one, two or three sections of varying profiles either used individually or in combination.

Picture frame mouldings were constructed locally from native and imported species of timber, mostly from the Araucaria genus, such as the local Hoop pine. These mouldings were purchased ‘in the raw’ — having no finish — directly from the manufacturer with the mouldings then being cut to size. The frames were mostly painted with colours selected by dealers to harmonize with the tonal values of paintings or left in the raw, being either waxed or polished — occasionally combinations of the two finishes can be found on a frame. Throughout Fairweather’s artistic career the mid-20th century modern aesthetic influenced the way in which his paintings were housed and ultimately the way in which they were presented to the public.

Following research into frame styles for the QAGOMA collection of Ian Fairweather paintings, the Conservation Framer designed and manufactured 10 frame sample profiles and finishes to suit his paintings. A selection of these profiles were then used to craft reproduction frames for the Fairweather paintings on display.

Anne Carter is Paintings Conservator, QAGOMA

Samantha Shellard is Paper Conservator, QAGOMA

Robert Zilli is Conservation Framer, QAGOMA

1 Gleeson, James. ‘An artist minus a soul: Fine work spoilt’. Sun, 20 November 1957.

2 26 Nov 1965 transcripts of interview between Hazel de berg, Bribie Island, National Library of Australia. Quoted in Bail, Murray. Fairweather. 2nd edn., Murdoch Books, Sydney, 2009. p265

3 26 Nov 1965 transcripts of interview between Hazel de berg, Bribie Island, National Library of Australia. Quoted in Bail, Murray. Fairweather. 2nd edn., Murdoch Books, Sydney, 2009. p265.

4 Bail, Murray. Fairweather. 2nd edn., Murdoch Books, Sydney, 2009. p266

A selection of Ian Fairweather’s works are on permanent display in the Australian Art Collection, Queensland Art Gallery (QAG)

Featured image: Looking for clues to date the works

#QAGOMA