These works, recently acquired for the Collection with the generous support of Alex and Kitty Mackay, illustrate the processes, and challenges, of the artist’s gender modification. The works will feature in ‘GOMA Q: Contemporary Queensland Art’, opening 11 July 2015.

As a young teen, Tyza Stewart was frequently preoccupied with a desire to be a man, and more explicitly, a gay man. More than a precocious curiosity about the differences between the human form and a developing sexuality, Tyza’s sense of self grew with new information about masculinity, homosexuality, gender identity and gender modification. Many works present the artist’s head atop a muscular male body, painted as both a picture of personal desire and a demonstration of will against the expectations of society. Some more recent works diarise the artist’s process of gender modification, including two new acquisitions purchased with funds from Alex and Kitty Mackay.

Painted in shades of violet, Untitled 2014 presents the artist side on, looking away from the viewer with discreet determination. The somewhat matter-of-fact pose throws a tight cluster of pimples along the jaw line into the centre of the composition. Restrained and eloquent, Tyza infuses the scene with an illustrative quality, as if it was composed chiefly to present certain facts — namely, that these pimples are one of the more common signs of testosterone treatment that individuals can expect as part of the modification process, and as such have also become one of the artist’s first empirical observations to reflect upon. On balance, bad skin seems a fairly minor issue; and so the choice of subject here perhaps reveals the artist’s dry sense of humor as it brushes against a culture that cultivates and exploits our vanity.

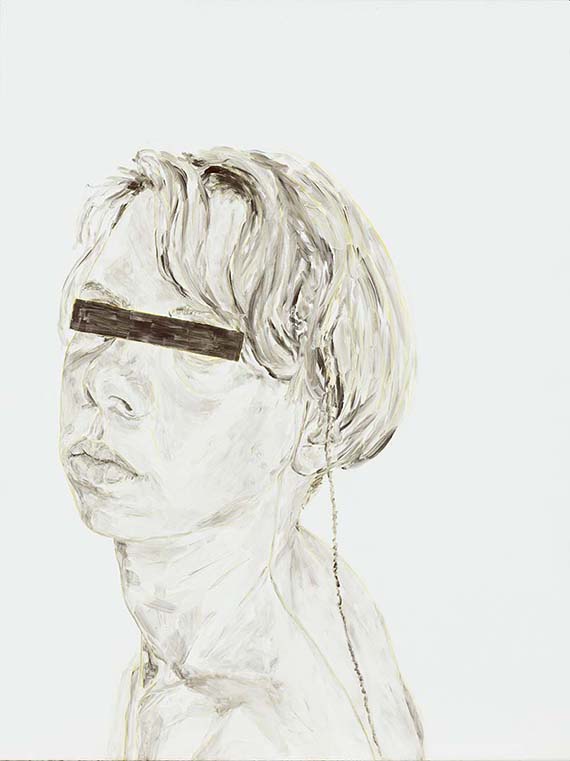

Untitled 2014 makes note of the relatively impersonal experience of being a medical subject or patient in the healthcare system, and on a more subtle level how the conventions and procedures associated with the medical field can test an individual’s self-perceptions. While this is clearly a self‑portrait, we can also see that, by drawing a thick black line across the eyes, the artist has rendered the subject anonymous. This is a standard practice in medical text books to protect (and perhaps neutralise) a subject’s identity. Talking about discovery of clinical interpretations of gender modification, Tyza has previously said that:

My dad had some psychology text books from uni and I’d been reading about that a bit and it just seemed like a medicalised disorder, and it wasn’t portrayed as anything that could be a gender identity. So I think it was a long time before I realised that it could be an identity, something that’s not bad, and not medicalised.1

Tyza has previously spoken of the political aspects of asserting a transgender identity, stating that, ‘by resisting and engaging with popular understandings of transsexual narratives, I aim to highlight some alternatives to the strict binary understandings of gender that constantly proliferate within our society’.2 In the influential book Gender Trouble (1990), cultural theorist Judith Butler similarly describes how we learn to understand ourselves through a strict binary system, coining the term ‘gender performativity’ to describe gender as the effect of repeated feminine or masculine acts rather than something innate. Butler posits that what is considered ‘true gender’ is in fact a narrative, sustained by ‘the tacit collective agreement to perform, produce, and sustain discrete and polar genders . . . and the punishments that attend not agreeing to believe in them’.3

Stylistically accomplished and uniquely disarming, Tyza Stewart’s painting practice grapples with and ultimately disregards the masculine/ feminine binary gender norms and the limitations they impose on the individual in favor of a concept of spectrums. Yet, while this work creates space for individual difference by asserting an identity, it is perhaps the freedom of expectation that it fosters in its audience that is the larger, and more subtle, achievement.

Endnotes

1 Dewi Cook, ‘Painter Tyza Stewart blurs the lines drawn between male and female’, Sydney Morning Herald, 27 September 2013, http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/art-and-design/painter-tyza-stewart-blurs-the-lines-drawn-between-male-and-female-20130926-2ugry.html, accessed 19 November 2014.

2 Alison Kubler, ‘Introducing: Tyza Stewart’, Manuscript 2014, http://www.manuscriptdaily.com/2014/08/introducing-tyza-stewart/, accessed 19 September 2014.

3 Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (Subversive Bodily Acts, IV Bodily Inscriptions, Performative Subversions), Routledge, New York, 1990, p.179.