A multitude of voices in a nation’s cultural history are often dimmed by the emergence of a dominant narrative. In the case of Aboriginal art in the last half of the twentieth century, that narrative is the story of the desert painting movements. However, it is important and valuable to consider the experiences and artworks of Aboriginal artists from other parts of the country.

A number of important engagements occurred between Aboriginal artists and the wider art world prior to the emergence of desert or ‘dot’ painting from Papunya in 1971–72. The most notable of these, of course, is the story of Albert Namatjira and the Hermannsburg School of watercolour landscape painting, but others of the same period include Western Australian carvers Jack Wherra and Butcher Joe Nangan, watercolour painter Wattie Kurrawarra, as well as painters Joe Rootsey and Segar Passi from Queensland, among many others.

The Barambah Pottery was one such example of thriving cultural activity in Queensland, a pottery studio based in the Aboriginal settlement of Cherbourg, previously Barambah Aboriginal Reserve. It was inspired in part by the work of Michael Cardew (1901–83), the eminent English studio potter who had previously worked with communities in West Africa — Nigeria and Gold Coast (now Ghana) — then in 1968 at Aboriginal communities in Bagot (Darwin) and on Bathurst Island (Tiwi Pottery). The Barambah Pottery was established around 1967, following a feasibility study by Queensland potters Carl McConnell and Jeff Shaw, with McConnell serving as the inaugural instructor.1

The pottery was somewhat anomalous: it was set up through a regular state government departmental process — as was nearly everything officially related to Aboriginal people, especially those living in the reserves system — but was conceived and locally managed by well-known artists, who envisioned it as a place of art making rather than as a government curio production depot. McConnell, noted as the most important potter of the post-World War Two generation in Queensland, left after less than a year, after the Department of Aboriginal and Islander Advancement suggested that he build the promised pottery studio and kiln himself. The attitudes of departmental officials would plague the pottery throughout its existence.

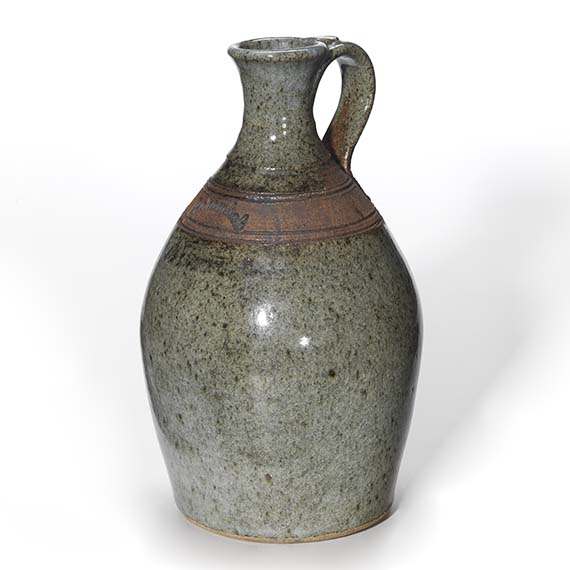

In the six years between the departure of McConnell and the arrival of Kevin Grealy in June 1974, the work of the Barambah Pottery was largely driven by officials of the Queensland Government’s Department of Native Affairs, which insisted that the potters make stereotypical works based on ‘market research’, which suggested that Jolliffe-style cartoons, symbols and designs from other parts of the country, and Aboriginal faces on ashtrays, would sell best.2 After Grealy’s arrival, and during his tenure until March 1976, the artists were afforded a little more artistic freedom, though departmental officials still tried to control the centre’s output.3 The pots produced often featured ‘Cherbourg style’ art, in which stylised X-ray and decorated animal paintings — reflective of north-Queensland rock art (where many of Cherbourg’s residents originated) — and particular line and dot motifs predominated. This visual repertoire was mixed during this period with an elegance of form and Japanese-style brushwork, the hallmark of potters such as Cardew, McConnell and Grealy. Although the pottery was quite successful and was well-known both locally and nationally, many specifics about its operation are still unknown and details about the individual artists remain scarce. A wealth of information likely exists in departmental files, awaiting further research and discovery.

These works represent a period in Queensland art during which, for one group of artists, production was controlled by the state. Yet the artists here showed that a mastery of the medium — and the subtle subversion of departmental dictation — meant works of great quality could still be produced.

Endnotes

1 Kevin Grealy, ‘Barambah Pottery, Cherbourg’, in Pottery in Australia, vol.16, no.2, 1977, pp.3–7.

2 Grealy.

3 Grealy.