Public collections in Queensland have few outstanding examples of the work of our early artists. Of the major works dating from the 19th century, the Panorama of Brisbane 1880 by JA (Joseph Augustine) Clarke (1840–90), Queensland‘s first professional artist and art teacher, is undoubtedly the best known and most significant.1 Visit the nearly 4–metre–long panorama in the Australian Art Collection at the Queensland Art Gallery and see if you can recognise the landmark buildings still standing.

Watch: ‘Panorama of Brisbane’ up close

JA (Joseph Augustine) Clarke, Australia 1840–90 / Panorama of Brisbane 1880 / Oil on canvas / 137 x 366cm / Collection: Queensland Museum

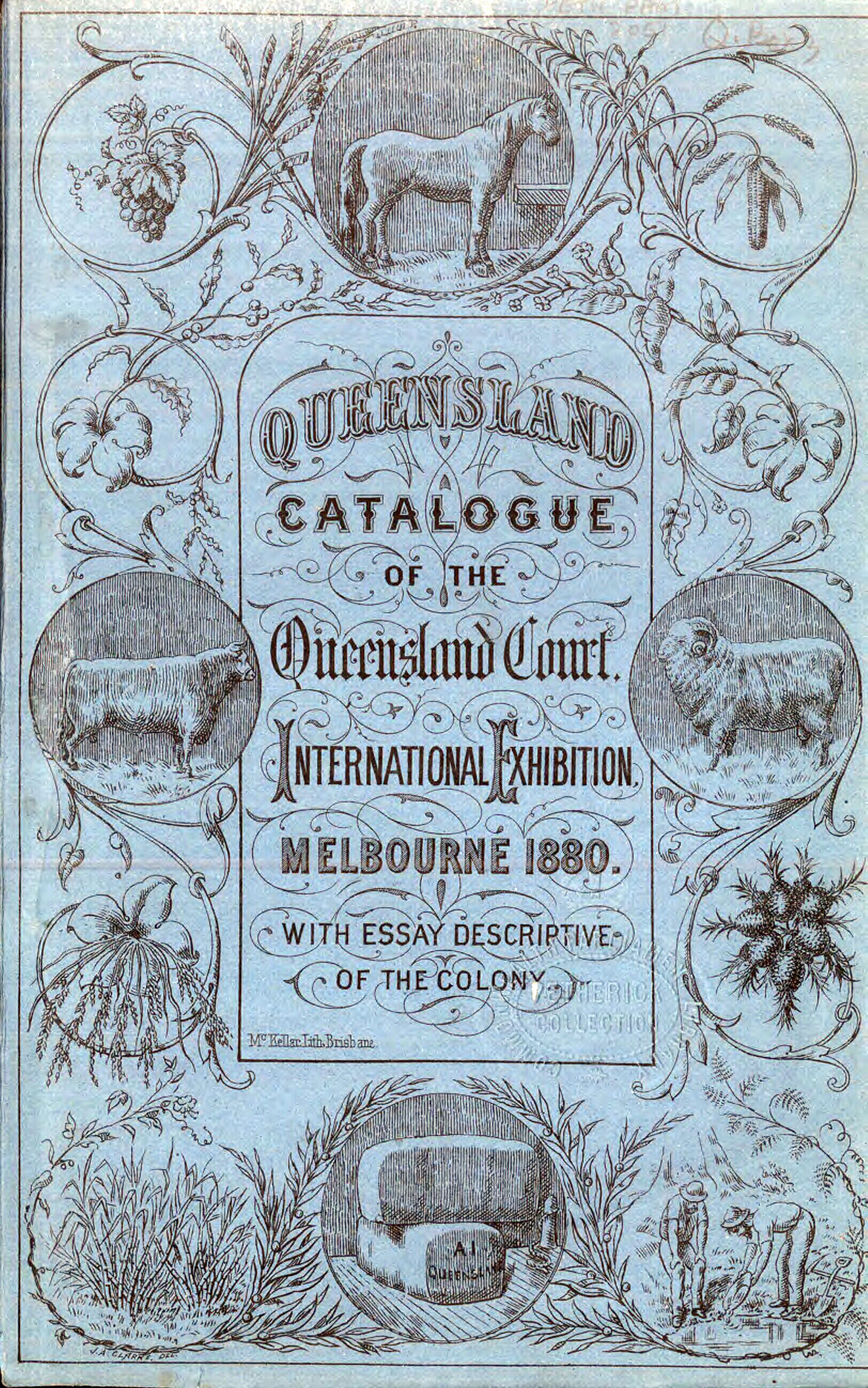

Clarke’s ‘grand picture’2 was commissioned by the Queensland Government for display at the Melbourne International Exhibition of 1880–81. This event, directing world attention to civilisation’s advances at the antipodes, was to open in Melbourne‘s new Exhibition Building on 1 October 1880. Queensland, the youngest of the Australian colonies, was slow in deciding to mount a court (as the various national or thematic sections of exhibitions were called), finally agreeing in March 1880, only six months before the event’s opening. It seems that Clarke’s commission to paint the picture was also a last-minute decision, as he had to suspend his regular duties as an art teacher to meet the deadline. He was still adding finishing touches to his large 4½ x 12ft (137 x 366cm) canvas in September that year,3 and was dissatisfied with its state of completion. He sought permission to continue working on the painting ‘for three weeks in a month’ on its return from Melbourne, without adding to his fee of £136/10/-.4 Before the painting was sent south it was put into an ornate gilt frame made by Charles Knights & Co, Brisbane’s leading gilders and picture frame makers of the time.

DELVE DEEPER: Read our Queensland Stories

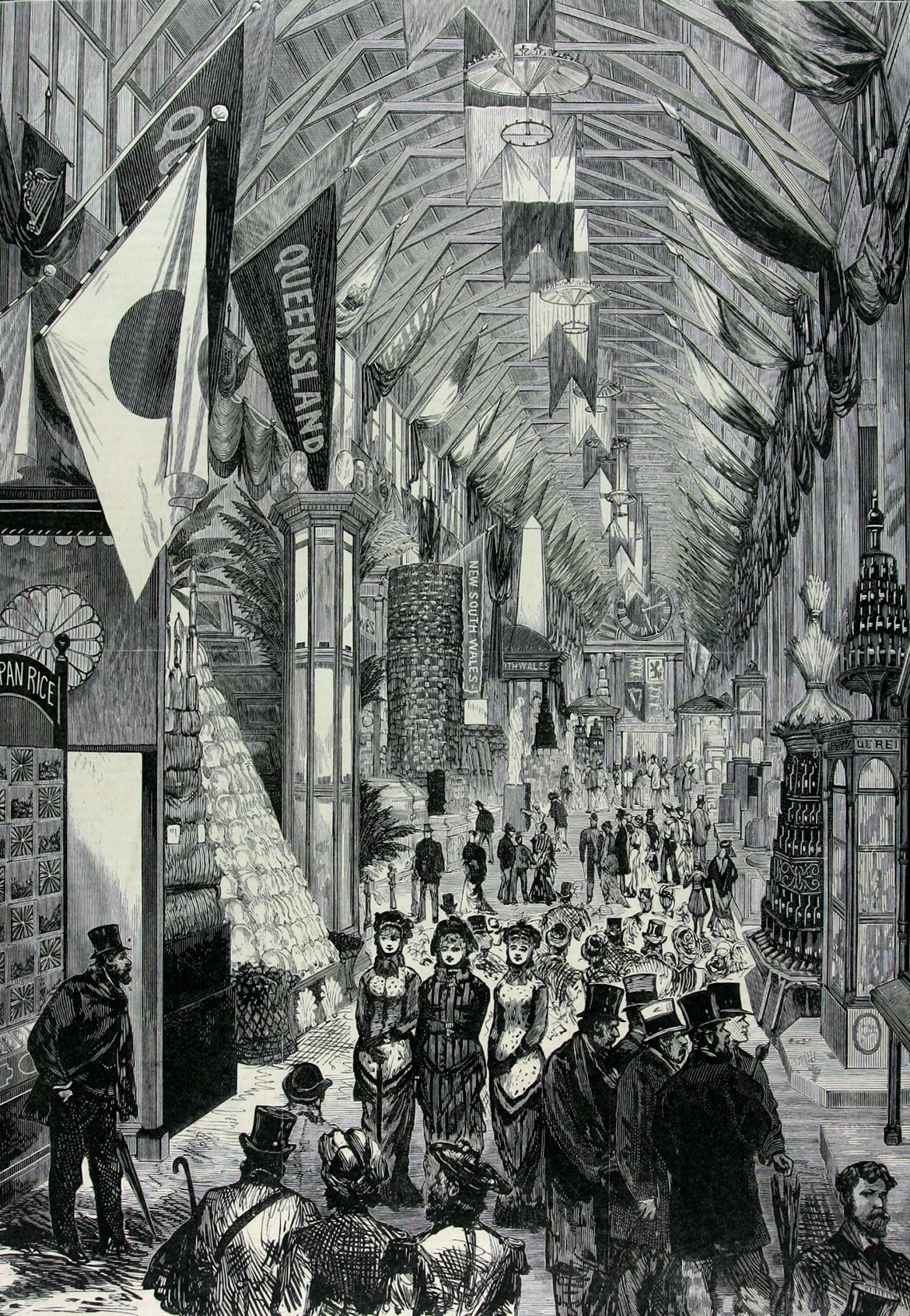

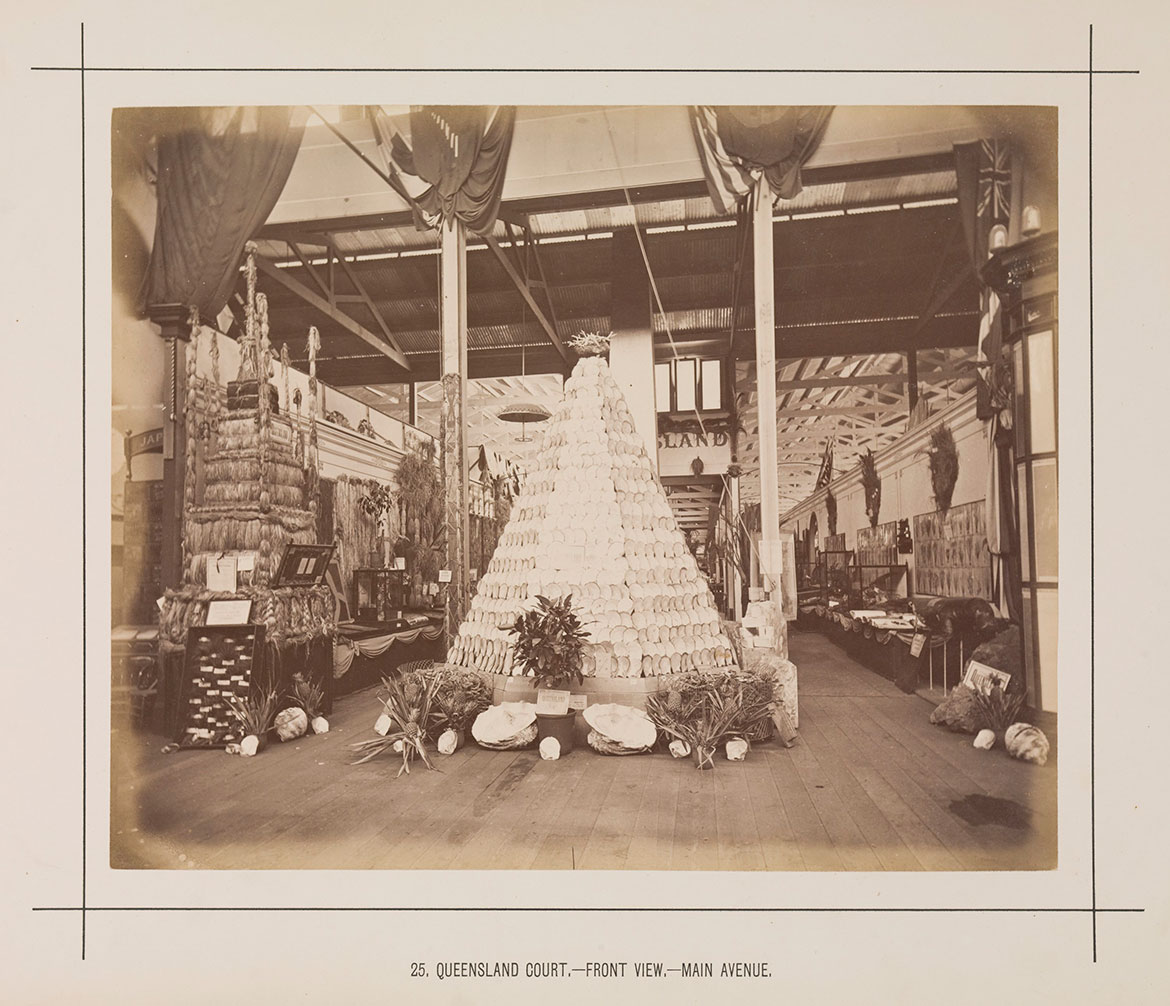

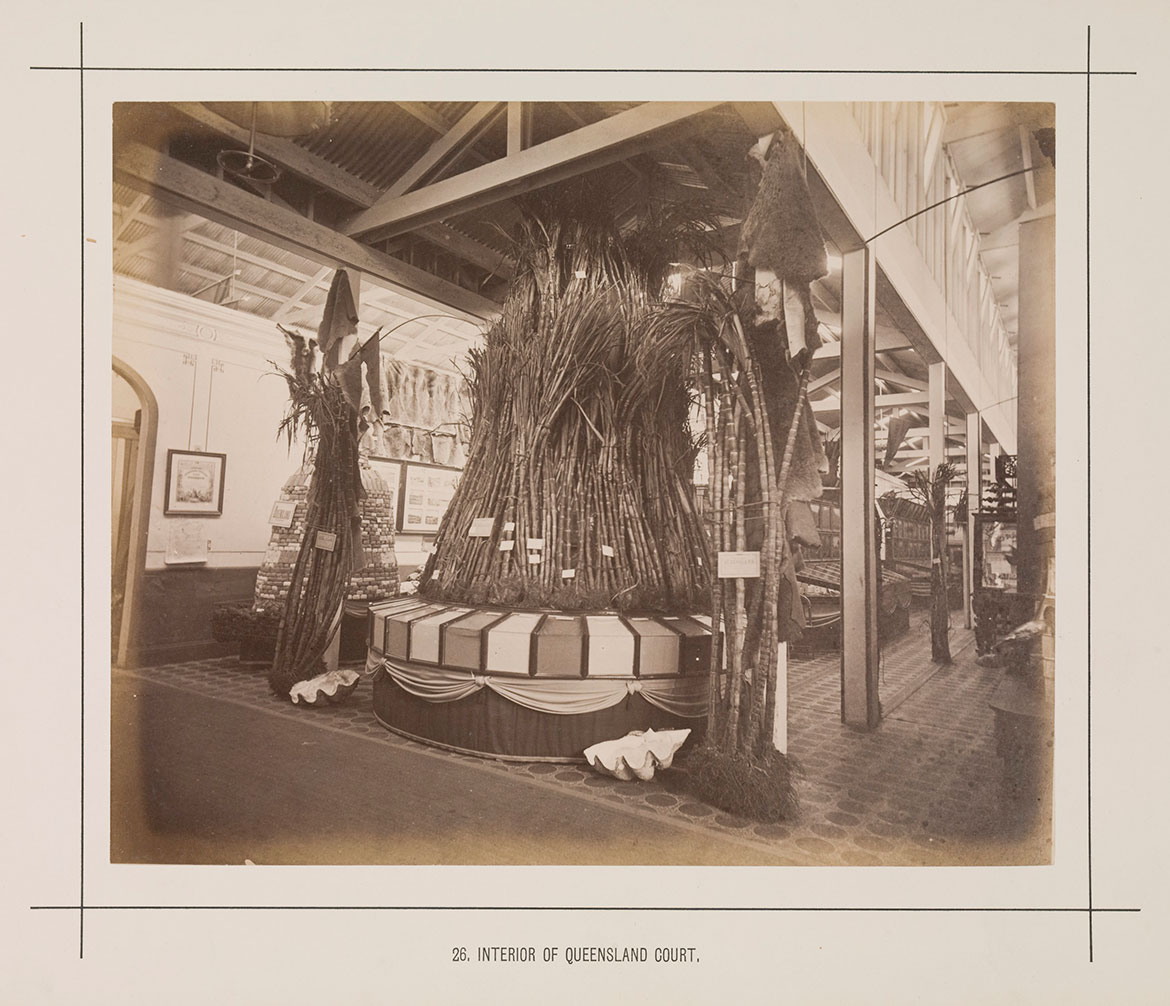

Due to Queensland’s late entry into the Melbourne exhibition its court was relatively small, in the annexe rather than the main building, and occupying a long narrow space with a low ceiling. The court was modest compared with the spectacular shows the colony made over the years at London exhibitions.5 It presented Queensland as a tropical paradise, a resource-rich frontier only waiting for investors and immigrants to exploit its riches. Unlike other courts showcasing arts and manufactured goods, it abounded in natural, agricultural and pastoral products—a veritable ‘museum of curiosities’ wrote the Argus reporter.6

Its contents included trophies and obelisks of tropical products and minerals; hides, skins, natural history specimens and the like filling the walls and display cases; and tropical ferns and fruits, potted plants and clamshells littering the floor. This melange was accompanied by maps, charts and photographs, notably geologist Richard Daintree‘s painted photographs of Queensland landscape. Clarke’s Panorama of Brisbane hung at the back of the court, above the office of Queensland‘s Commissioner for the exhibition, George King, a well-known pastoralist of Gowrie, Toowoomba.

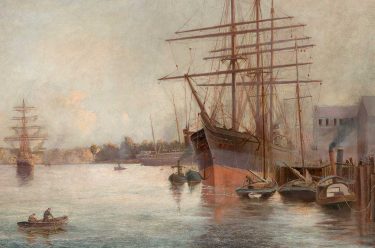

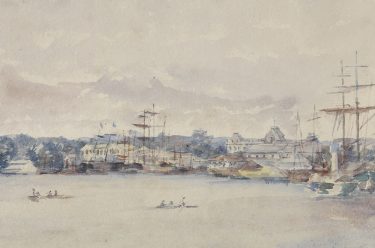

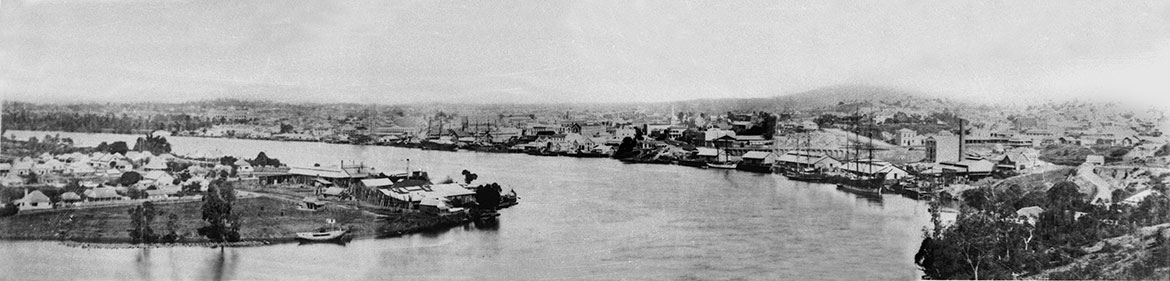

The purpose of Clarke’s panorama was, in the rhetoric of the time, to record the progress of civilisation in Brisbane since the advent of European settlement 56 years earlier. In a wide view extending from Kangaroo Point to Spring Hill, the city‘s appurtenances of civilisation are clearly visible — its wharves, warehouses, factories, shops, churches, residences, and above all, its fine public buildings, including Parliament House. In viewing the painting, the Argus reporter was relieved to see that except for the windmill (then known as the Observatory) all traces of Brisbane‘s convict past had been ‘well nigh obliterated’.7 Such panoramas were often used in the late 19th century to record the growth of towns and cities, mostly adopting the new technique of photography. Australia‘s best known example was a massive panorama of Sydney shown by New South Wales at the United States Centennial Exhibition, Philadelphia in 1876. This, the work of Bernard Holtermann and his assistant Charles Bayliss, comprised 23 photographs joined together to form a continuous 978cm sweep of the city and its suburbs.

Clarke’s panorama depicted Brisbane from a high vantage point on Bowen Terrace, in today’s suburb of New Farm, just east of where the Story Bridge now stands. The site was called ‘Judges’ View’ in pre-Separation days because visiting New South Wales judges used to stroll there to view the picturesque scene below.8 It was an obvious site for Clarke to choose, having been used by earlier artists Conrad Martens and Henry Douglas-Scott-Montague during the 1850s. The following is a contemporary description of Clarke’s painting:

‘The view is … a very comprehensive one, embracing as it does the greater part of North and South Brisbane and Spring Hill, with Taylor’s Range, and the more distant Little Liverpool Range as a background. The artist has succeeded admirably with those most difficult subjects — sky and water, and it is needless therefore to say that the remainder of the landscape is artistically painted. The river in front of Birley’s saw mills [Kangaroo Point] forms the immediate foreground, to which great life is imparted by a barque being towed up, the ―wake‖ produced by the tug being capitally managed. Spring Hill in the middle distance on the right of the picture is full of well–worked out detail, and the range of hills at the back, terminating in One Tree Hill, has an admirable effect. Parliament House is a prominent object in the centre of the picture, which, as a whole, will give strangers an excellent idea of the capital of Queensland. The artist has done in this work what so many of his brethren of the bush fail in — he has made his ships look like ships.’9

The painting is not only a valuable record of Brisbane’s buildings in 1880, but also the key work of Queensland’s first important artist. English born and trained Joseph Augustine Clarke was a recognised topographical artist when he arrived here in the mid-1860s. In 1863 he had been appointed instructor in topographical drawing at the Imperial Central School at Poona, India. In Brisbane, he took a leading role in cultural life: as a prolific illustrator of newspapers, books and other publications; as a decorative artist; as co-founder, with the poet James Brunton Stephens, of the Queensland Punch newspaper; as a founding member the Johnsonian Club; and as a participant in early art exhibitions. Clarke is best remembered as a pioneer art teacher. In 1869–74 he was the only drawing teacher in Queensland Government schools, later also teaching at the Brisbane Girls’ Grammar School and All Hallows’ School. In 1881 he initiated art classes at the Brisbane School of Arts, at first offering drawing and later also painting and clay modelling.10 It was largely due to him that the School of Arts’ classes became a Technical College in 1884.11

At the Melbourne exhibition Clarke’s panorama was well received by local critics, first by C.L. Fletcher, an artist who was employed as curator of the Fine Arts galleries and assisted Queensland officials in unpacking and hanging the huge painting.12 Its topographical accuracy led another critic to mistake it for a coloured photograph,13 possibly confused by the painterly qualities of Daintree’s photographs hanging nearby in the Queensland court. Clarke also achieved success in the exhibition’s Fine Arts section, exhibiting paintings, newspaper illustrations and an etching, Creek Crossing at Ashgrove, near Brisbane; he won a third order of merit for the etching.14 The Fine Arts section was extensive and included works by members of London‘s Royal Academy and the Royal Scottish Academy; a selection from Queen Victoria’s own collection; Italian works; and works by Australia’s best-known artists, including Louis Buvelot, Eugene von Guerard, Julian Ashton and Ellis Rowan. It was no mean feat for works by a Brisbane art teacher to be noticed among such company.

After his Panorama of Brisbane returned from Melbourne, Clarke spent some time ‘touching up and improving’ it before it was shown again at Brisbane’s National Association exhibition of August 1881.15 Soon afterwards the Queensland Government gave the painting to the Queensland Museum (there was then no state gallery) on condition that it would be ‘properly hung… well cared for and returned to the Colonial Secretary when required’.16 The painting was displayed prominently in the museum’s old William Street building, confronting ‘the visitor as he enters … straight in front’.17 It was so popular that by 1882 the Brisbane photographic firm Mathewson and Co. was producing ‘handsome’ photographic copies for sale, in no less than three sizes.18

This collaboration with the Mathewson firm provides a clue as to how Clarke achieved his topographical accuracy. His painting shows the same panoramic view of Brisbane from Bowen Terrace used by Thomas Mathewson in his well-known photograph of 1881, and possibly in other earlier photographs.19 It was not uncommon for 19th-century artists to base their pictures on photographs; for instance, J.C. Armytage and Thomas Baines produced scenes of Brisbane without ever having visited the city.

Later, when the Queensland Museum moved to Brisbane‘s former Exhibition Building on Gregory Terrace in 1889, Clarke’s panorama remained a popular exhibit, so much so that it was at times damaged by visitors pointing eagerly at familiar landmarks. In 1959 it became the centrepiece of the Queensland Museum’s historical exhibition for the State‘s centennial celebrations. Today it is on display in the Queensland Art Gallery’s Australian Art Collection, on long-term loan from the museum.

Dr Judith McKay is a former Queensland Museum curator. She was guest curator of the Queensland Art Gallery‘s retrospective exhibitions on the noted Queensland sculptors Harold Parker (1993) and Daphne Mayo (2011).

Endnotes

1 This article is an updated version of Judith McKay‘s earlier publication: ‘JA Clarke‘s ― grand picture’ of Brisbane‘, Australiana, vol. 10, no. 4, November 1988, pp. 119–21.

2 Brisbane Courier, 11 August 1881, p. 3.

3 Telegraph, 14 September 1880, p. 2

4 George King (Executive Commissioner) to Colonial Secretary, 19 November 1880, COL/A302, 1880/6115, Queensland State Archives.

5 Judith McKay, Showing Off: Queensland at World Expositions 1862 to 1988 (Central Queensland University Press and Queensland Museum, Brisbane, 2004).

6 Argus Exhibition Supplement, 6 October 1880, p. 14.

7 Argus Exhibition Supplement, 15 October 1880, p. 30.

8 Brisbane Courier, 20 May 1882, p. 3.

9 Telegraph, 14 September 1880, p. 2.

10 In 1888–90 one of Clarke‘s modelling students was Harold Parker, later to win international acclaim as a sculptor.

11 Judith McKay, entry for Joseph Augustine Clarke in Design & Art Australia Online https://www.daao.org.au/bio/joseph-augustus-clarke/biography/, accessed 30 October 2020.

12 George King to Colonial Secretary, 19 November 1880, op. cit.

13 Brisbane Courier, 11 August 1881, p. 3.

14 Melbourne International Exhibition, 1880–81, Official Record (Mason, Firth & McCutcheon, Melbourne, 1882), p. 399 – Queensland.

15 Brisbane Courier, 11 August 1881, p. 3.

16 A.H. Palmer to Queensland Museum Chairman of Trustees, 7 October 1881, Queensland Museum inwards correspondence 81/1949.

17 Report of a visit to the Queensland Museum, Brisbane Courier, 24 January 1883, p. 5.

18 Brisbane Courier, 8 May 1882, p. 2.

19 Mathewson‘s photograph, State Library of Queensland neg. no 104075, is dated as 1881; however a slightly later date would be more accurate as Butler Bros’ Adelaide Street warehouse, at the far right, was not completed until May 1882.

On display in the Josephine Ulrick & Win Schubert Galleries, Australian Art Collection at the Queensland Art Gallery.

Additional research and supplementary material by Elliott Murray, Senior Digital Marketing Officer, based on QAGOMA curatorial research.

#QAGOMA