In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the fierce wildness and ‘savage beauty’ of Belle-Île, the small island off the coast of Quiberon in Brittany, France, exerted a powerful attraction to creative artists of a late-romantic temperament. Delve into why Belle-Île’s temperate climate, magnificent coastline, and 60 beaches became a magnet for Australian impressionist painter John Russell.

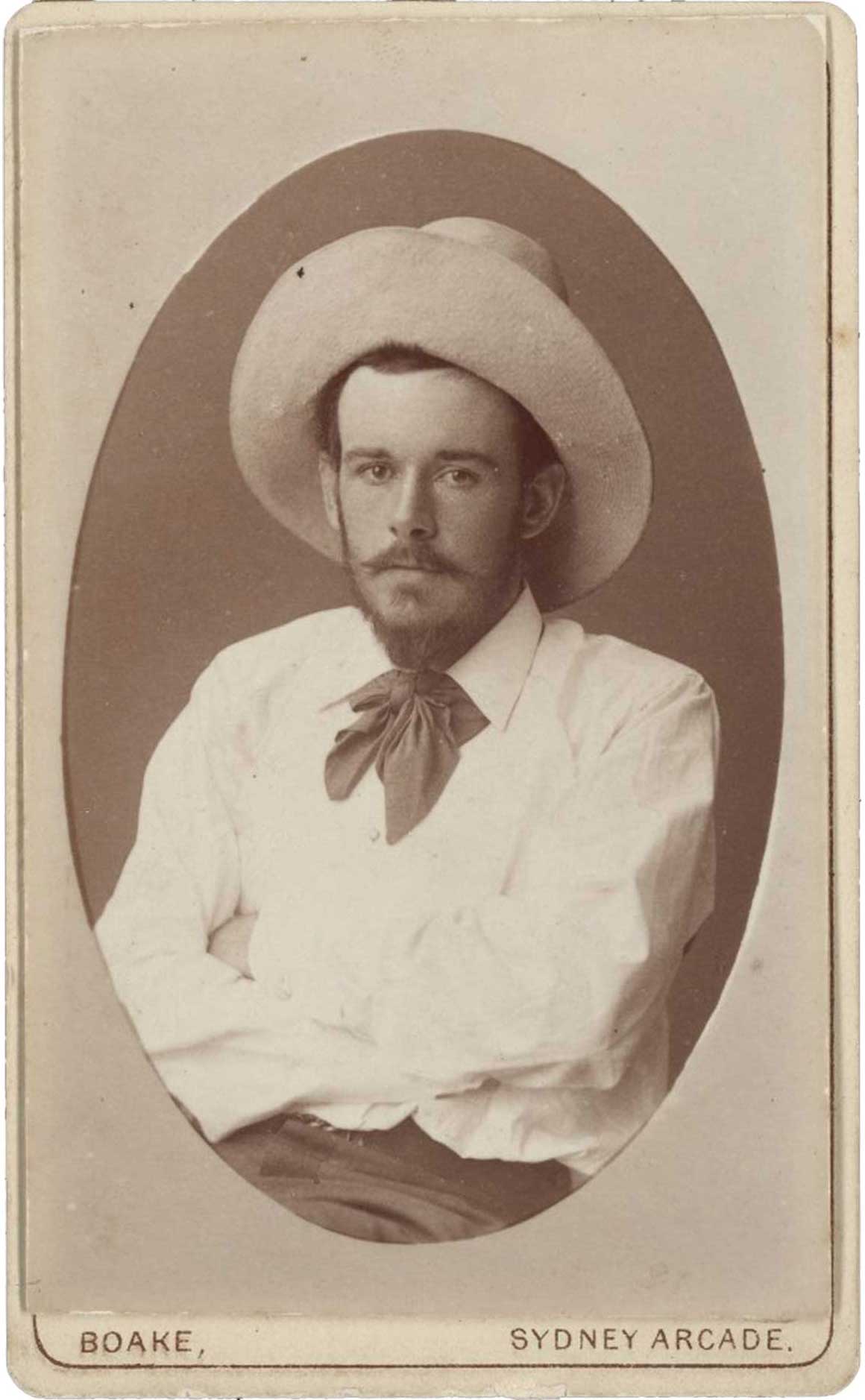

John Russell c.1883

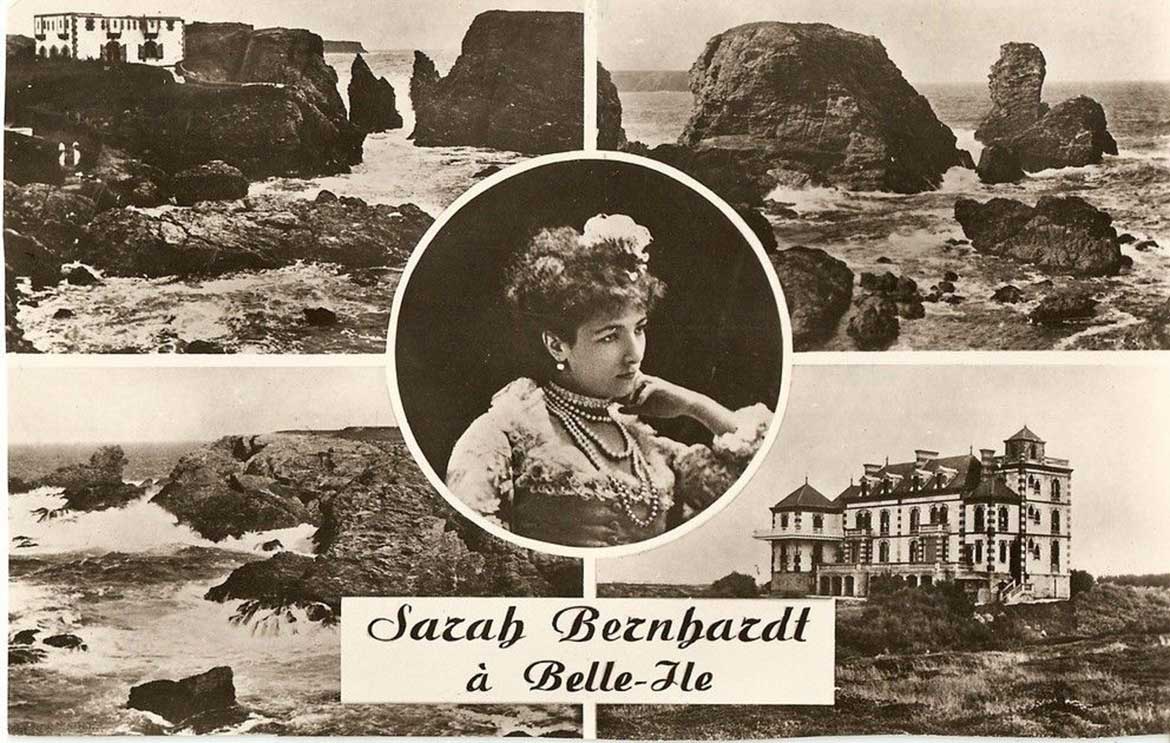

Located far from the fatigues of critical, competitive Paris (yet comfortably near by rail from Paris to Quiberon and then a one-hour steamer trip to Le Palais, the island’s tiny capital), at Belle-Île fraught nerves and sensitive natures could refresh themselves at Nature’s unspoiled source. As one famous summer resident, actress Sarah Bernhardt, reflected:

I like to come each year to this marvellous island and enjoy, amidst its simple and welcoming people, the whole charm of its wild beauty and grandness, and draw new artistic strength from its vivifying and restful sky.1

Belle-Île was far enough away to nourish a sense of being in another kingdom, another realm, where one could live by one’s own rules as did Sydney-born John (Peter) Russell with his wife Anna Maria Antonietta Mattiocco, called Marianna, and their six children.

Flat, relatively featureless, its beet-growing fields broken only by pines and tiny white cottages, Belle-Île was overwhelmingly a fishing island, centre of the vast sardine industry… the overwhelming attraction was the extraordinary westernmost coastline, ‘la côte sauvage’. Here where the land abruptly ends and drops into a boiling sea are to be found fantastically shaped rocks and grottoes formed over the centuries by that caressing and lashing sea.

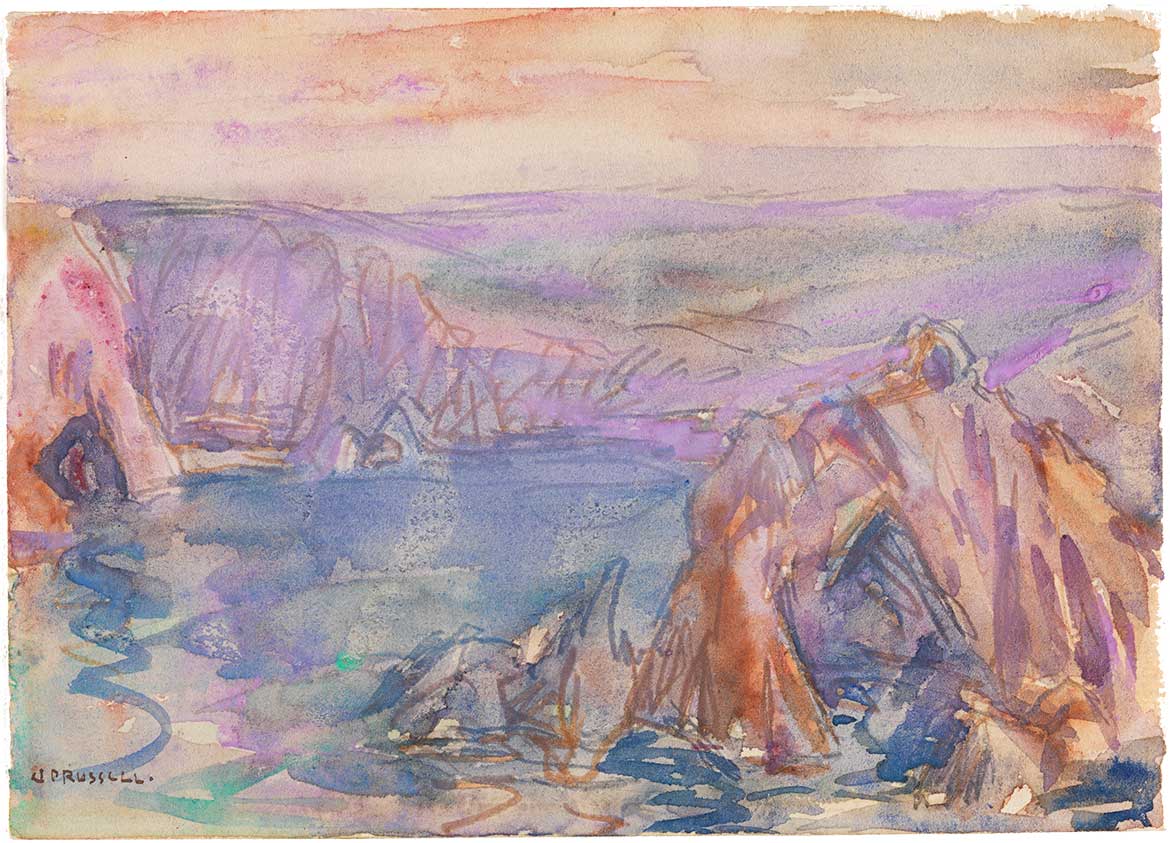

John Russell ‘Belle-Île’ c.1888-1909

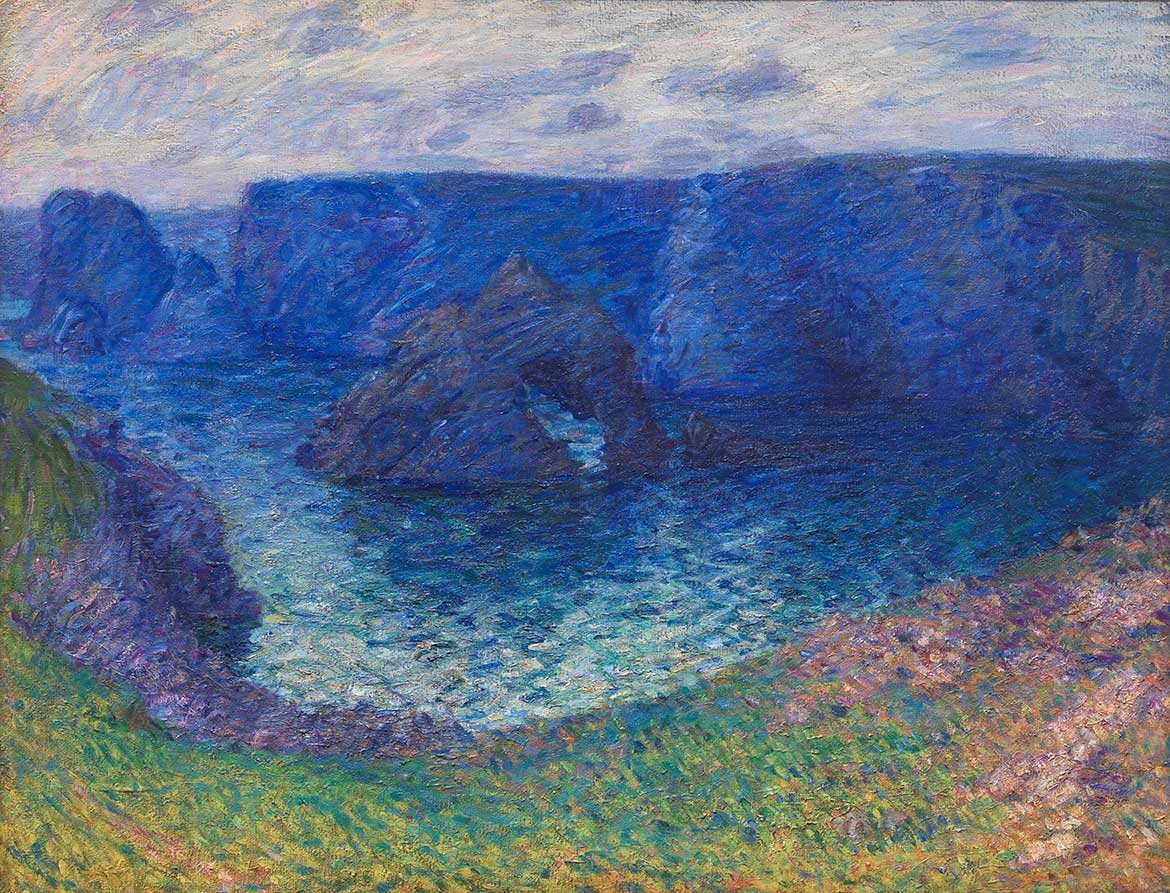

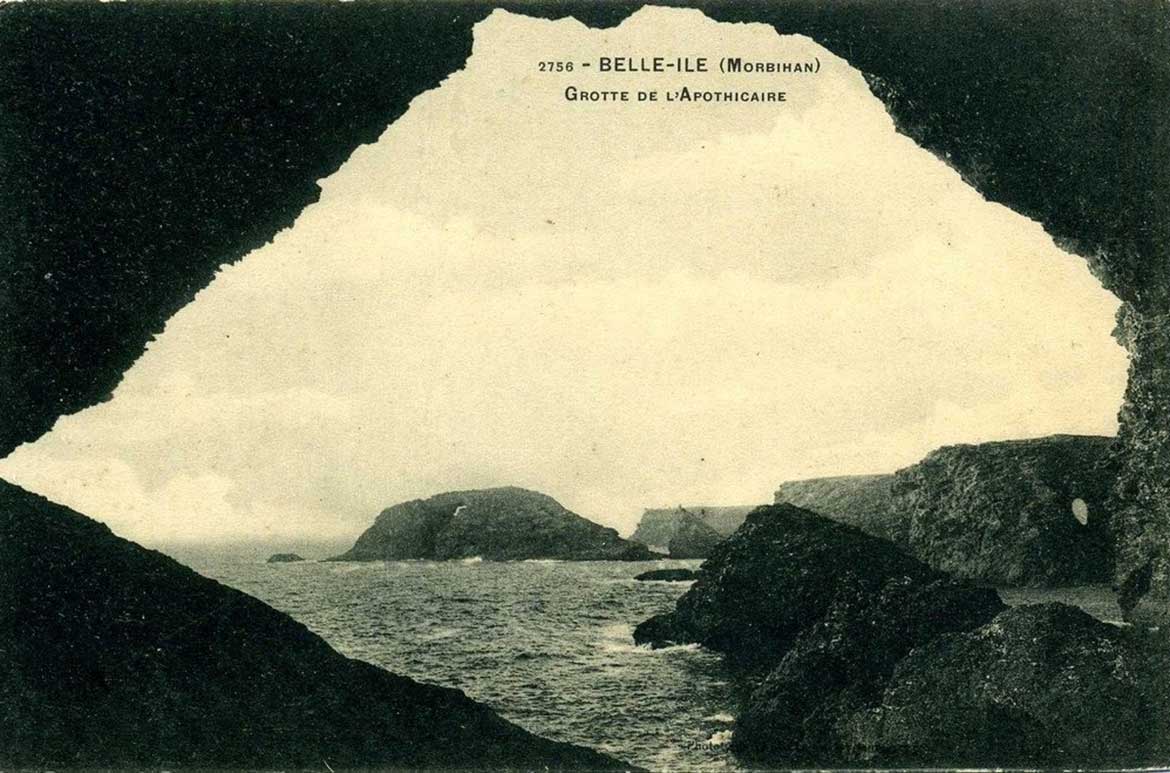

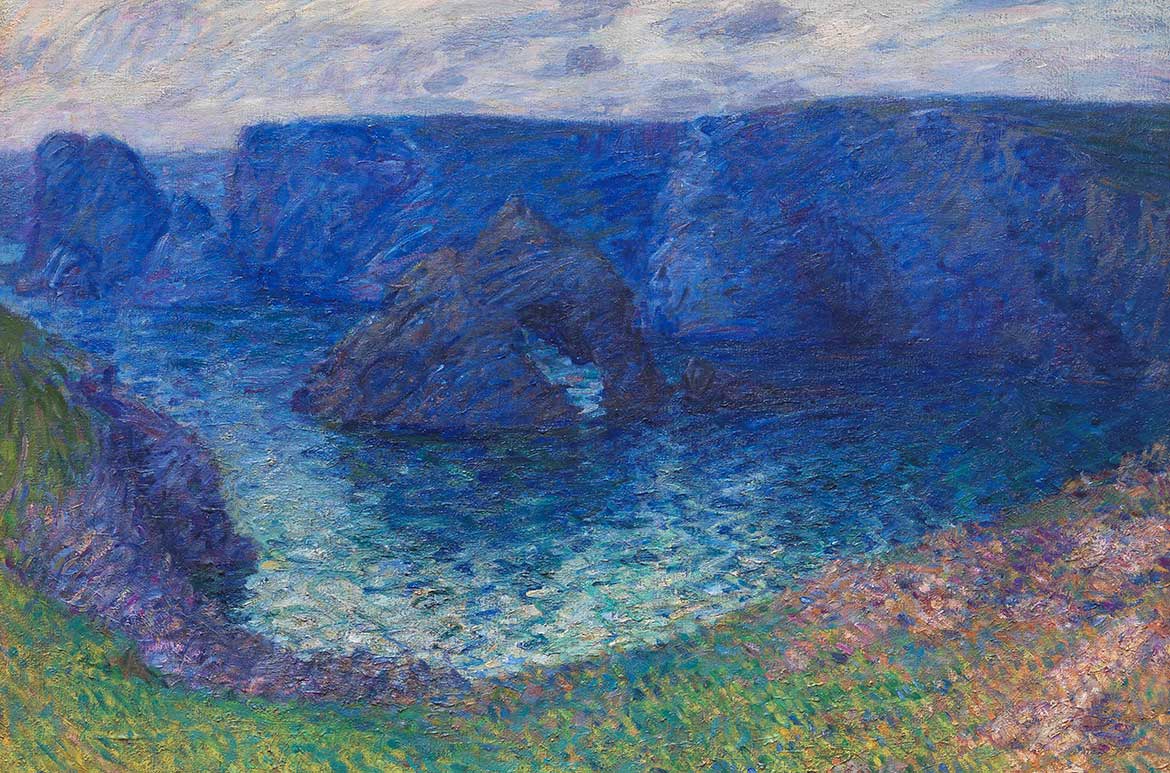

The strange shapes of the rocks had attracted fanciful names over the centuries. It was on the northernmost point of the island, Pointe des Poulains (Foals Headland), that Sarah Bernhardt built her ‘fort’. From here one can see the famous ‘Dog Rock’ — ‘Le Rocher du Chien’ — painted by both Claude Monet and John Peter Russell. Moving southwards, the rock islands ‘Roch Toull’ or ‘Roches percées’ are to be seen; next, the fantastic ‘Grotte de l’Apothicairerie’ accessible only by boat, where on one famous occasion Russell took a nervous but appreciative Auguste Rodin.

Further south, at the westernmost point of the island, is Port-Coton, behind which stands the great lighthouse. Here are to be found two tall thin adjoining rocks, known as ‘Les Aiguilles de Port-Coton’, or ‘needles’, named for the spumes of froth and spray that are whipped up from the narrow space of sea between them. Crossing the Port-Goulphar and rounding this westernmost point we come to another rocky inlet featuring a pierced rock in the centre, known as ‘La Roche Guibel’ — which is believed to be the actual subject of Roc Toul 1904-05, identified as such by former QAGOMA Director Raoul Mellish during a trip to the region. At the southernmost point of the island is yet another fantastic rocky cave, made famous by Alexandre Dumas père as the hiding place used by one of his three musketeers, Porthos, in the popular story published in 1844-45.

Russell settled on the island in 1888, building a rather grand house at Goulphar on the ‘côte sauvage’ at the point where the small Goulphar creek empties into the sea. From his high perch Russell could look out onto the Atlantic, but for his art he needed to develop a more intimate relationship with his preferred motifs — these strange rocks and the surrounding waters of the western seafront.

There was nothing unique about Russell selecting the rocks of the ‘côte sauvage’ as a painterly motif. Well before this, romantic travellers and artists had sought out such subject matter as a site for emotional expression… It was a time when island retreats were becoming fashionable for artists.

Monet visited the island in the autumn of 1886. Russell had been there since June with Marianna, and Monet wrote of their meeting to his friend Madame Hoschédé, saying that he believed himself to be alone in ‘ce coin perdu’ (this isolated place) but had encountered ‘un peintre américain’ who had come up to him and asked if he were Claude Monet ‘the prince of the impressionists’? After this introduction Monet warmed to him and allowed Russell to watch him work (a rare privilege), noting in a second letter that he had been on the island for four months and was married to an Italian model.2

Russell spent almost twenty years on the island during which time he remained obsessed with the sea and the ‘côte sauvage’ as a pictorial motif. Studies of his wife and children and of the local fishing identity Père Polyte provided the only distraction. Amongst his oeuvre the large body of paintings of the rocks, sea and sky dominates. Many motifs such as Les Aiguilles de Port-Coton, Le Rocher du Chien and the Port-Goulphar inlet were painted repeatedly, at different times of the day and in varying weather conditions and seasons.

John Russell ‘The Needles, Belle-Ile’ c.1890

Russell’s obsession with this subject was very much of its time. Around the turn of the century, interest in the sea and its surrounds as an artistic motif was reaching new heights. Art nouveau artists and designers delighted in abstracting forms from the natural shapes of seaweed, rocks and marine life forms.

Over these years, the settled domestic life that Russell had organised for himself on Belle-Île meant he had the time and concentration to experiment and to work through his understanding of the technical demands of pigments and media — a passion that had begun in his student years in Paris. There he had adopted the idea of painting a particular motif repeatedly in varying situations and conditions. In Paris it had been blossom trees and branches, inspired by his love of Japanese prints. On Belle-Île the repeated motif became the rocks of the ‘côte sauvage’.

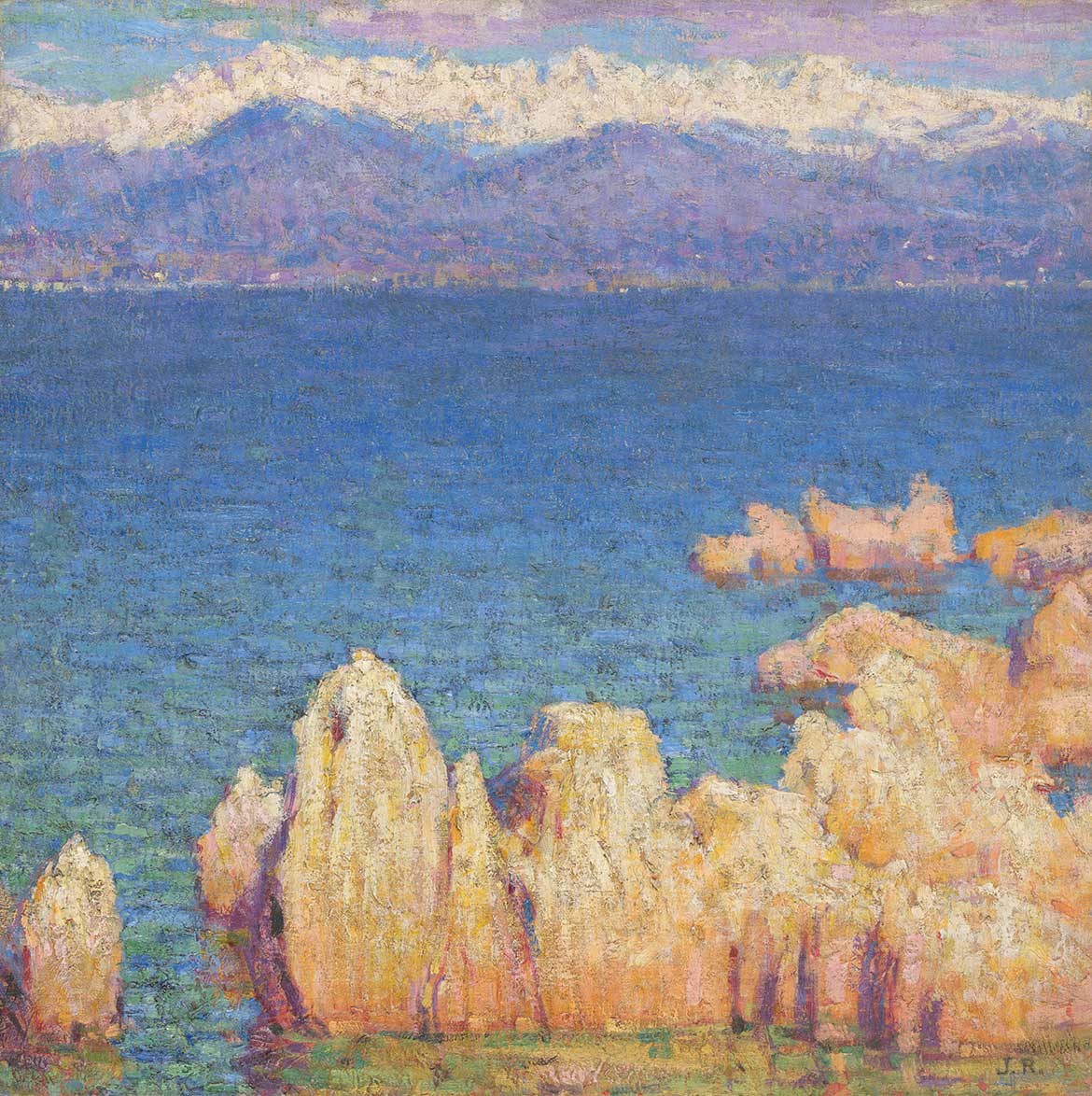

John Russell ‘Toul Rock (Guibel Rock)’ 1904-05

Roc Toul (Roche Guibel) is thought, on stylistic grounds, to have been painted about 1904-05, towards the end of Russell’s stay on the island [due to its’s] mastery of colour and sureness of touch. Roc Toul is unsigned and was not known to have been exhibited in Russell’s lifetime. However, it appears to have been highly thought of by the artist. He brought it with him to Paris when he sold his Belle-Île home in 1909. Two years later, at the commencement of the peripatetic lifestyle he was to adopt in the years before and after the First World War, he left the large canvas with a friend in Paris, a Monsieur Boisard, inscribing on the verso: ‘Dear Mr Boisard. Please keep this oil (of Orpheus) in the meantime while waiting for a 3rd Act? Kind regards John Russell 14/3/ll’.3 The references to Orpheus and a ‘3rd Act’ to come may refer to his perception of his own life, or they may refer to incidents in his daughter Jeanne’s career as a singer, which was then taking shape.

Roc Toul is a painting remarkable for its colour intensity. There is little doubt that colour is the real subject of the work. Russell’s use of brilliant cobalts and emerald greens, set off by the softer yellows and touches of rose madder, clothes the harsh rock shapes in an air of almost theatrical mystery. Nothing disturbs the colour harmonies; no other object is introduced into this magical world of iridescent blue rocks and their watery reflections, set against the yellow-green glow of the cliff top from which they are viewed. La Roche Guibel sits in the centre of the inlet, its arched opening providing a further glimpse of shimmering water. Russell’s brushwork is loose and confident. He has constructed webs and clouds of colour and has left well behind his earlier obsession with form. Roc Toul is a fine example of Russell’s mature colour painting. For him, as for Monet, the subject had become but the excuse for a display of sensuous colour harmony.

Edited extract from ‘L’allure de la Cote Sauvage: John Peter Russell Roc Toul‘ from Lynne Seear and Julie Ewington (eds). Brought to Light: Australian Art 1850-1965, Queensland Art Gallery, 1998. Dr Ann Galbally was Reader and Associate Professor of Fine Arts at the University of Melbourne.

Endnotes

(Translations from French to English by Annick Bouchet)

1 ‘J’aime à venir, chaque année, dans cette île admirable, au milieu de sa population simple et accueillante, goûter tout le charme de sa beauté sauvage, grandiose, et puiser sous son ciel vivifiant et reposant de nouvelles forces artistiques (Sarah Bernhardt, ¡n Gil Blas, 1896, quoted in Anatole Jakowsky, Belle-lle-en Mer, Editions La Nef de Paris, Paris, n.d. p.62).

2 Claude Monet, letters to Mme Hoschédé, 18 and 20 September 1886, Collection D. Wildenstein, Paris.

3 Cher M’ Boisard. Veuillez garder cette toile (d’Orphée) en attendant 3eme acte? Salute et en amité John Russell 14/3/11

Delve deeper into the Collection

John Russell ‘The route du Littoral on the West side of Cap d’Antibes, looking towards Nice, the Baie des Anges and the Alps’ c.1890s

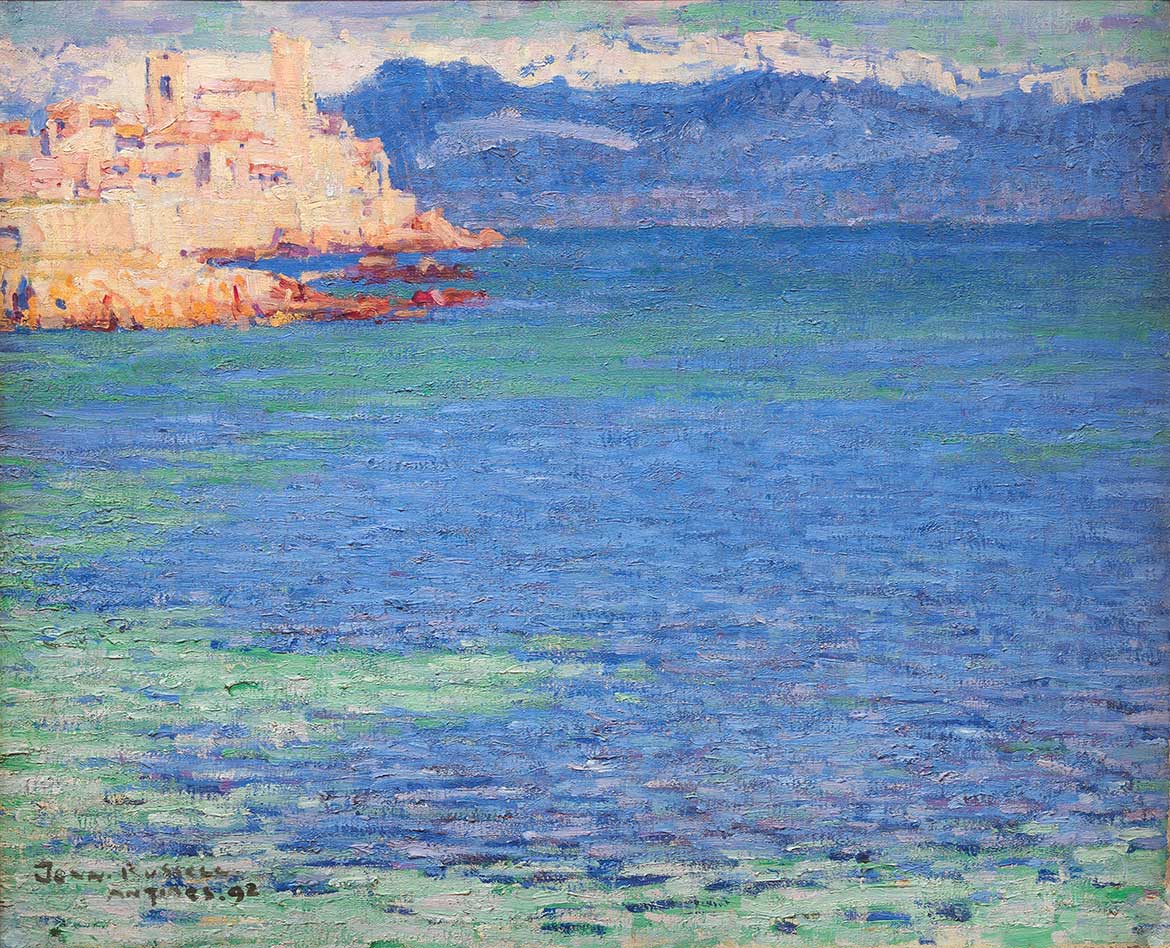

John Russell ‘View from Hotel Jouve, plage de la Sallis, looking towards the medieval walls and the Grimaldi Castle, Antibes’ 1892

John Russell ‘Rocks at Belle-Ile’ c.1900

John Russell ‘Calm sea at Morestil Point’ 1901

Featured image: John Russell Roc Toul (Roche Guibel) (Toul Rock (Guibel Rock)) 1904-05

#QAGOMA

Thankyou for this wonderful entree into the Artists of Belle Isle. About to travel there this year and having read this article and hearing about Russell is a very helpful grounding from which to appreciate the unique landscapes and rock formations which have inspired many famous artists. Russell would have been in the same era of art as an artist great aunt of mine, Mabel Coutts who would have travelled to Paris and maybe even knew Russell, and was perhaps part of the same bohemian art society frequenting Montmartre in the early 1900s.

It makes me wonder also if there are any works of my aunt Mabel, who studied in the Julian Ashton Art School, housed in the archives of Gagoma. I believe she may have exhibited there, or in the AGNSW from time to time. In the latter years of her life Mabel lived in a quaint cottage at 2 Chisholm Street, Greenwich, Sydney.

Hi Suzie. We don’t have any works by your Aunt Mabel in our Collection [https://collection.qagoma.qld.gov.au/], however there seems to be two works entered by ‘M B Coutts’ who exhibited in Sydney’s Archibald Prize of 1931. Thank you for your inquiry. Regards, QAGOMA