Sometimes we feel a sensation of freefall, perhaps when looking down from a high-rise building to the street below. We can also see from this perspective in floating views of the landscape from the Japanese Heian period, in the bird’s-eye view used by Australian Aboriginal artists to represent their traditional knowledge of country, and in artworks referencing early wartime aerial photography.1

raised through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation Appeal / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Kota Ezawa

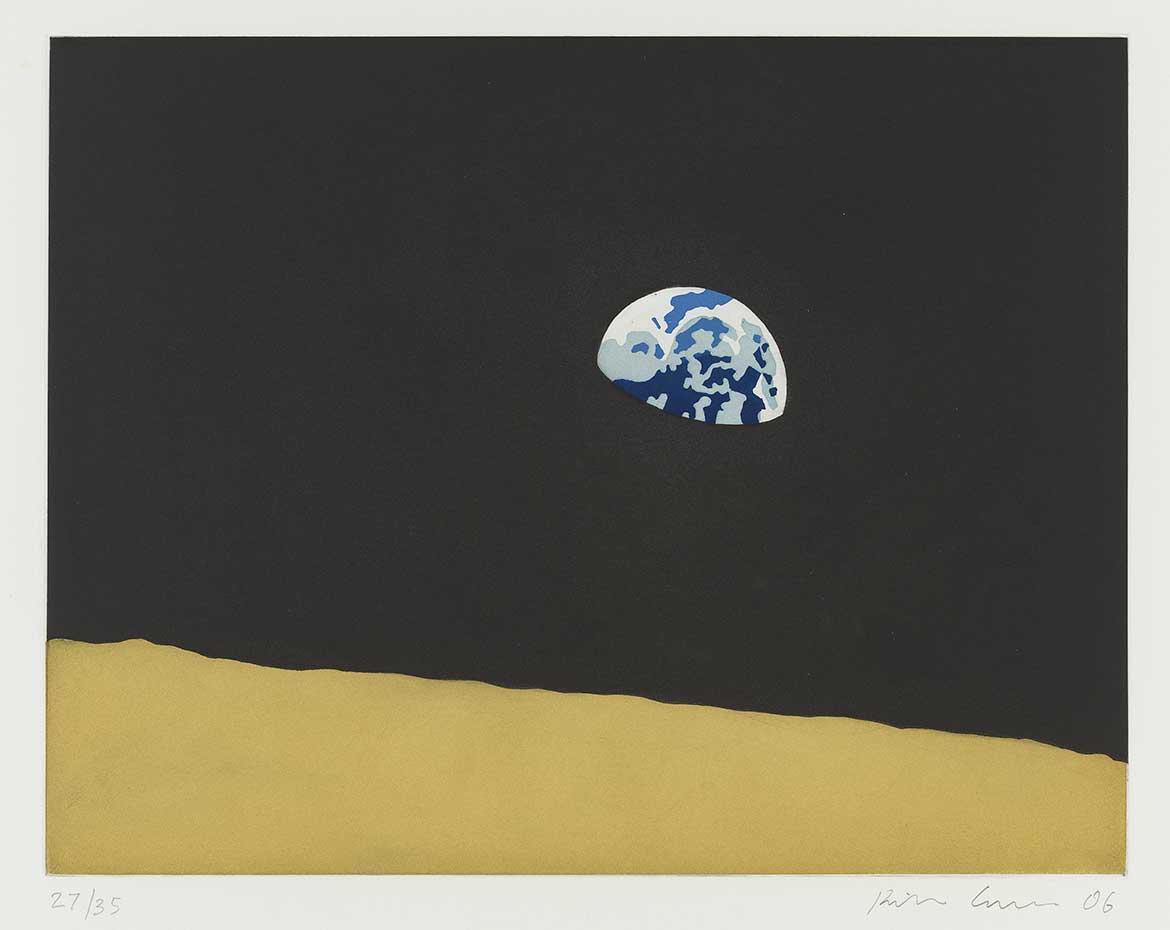

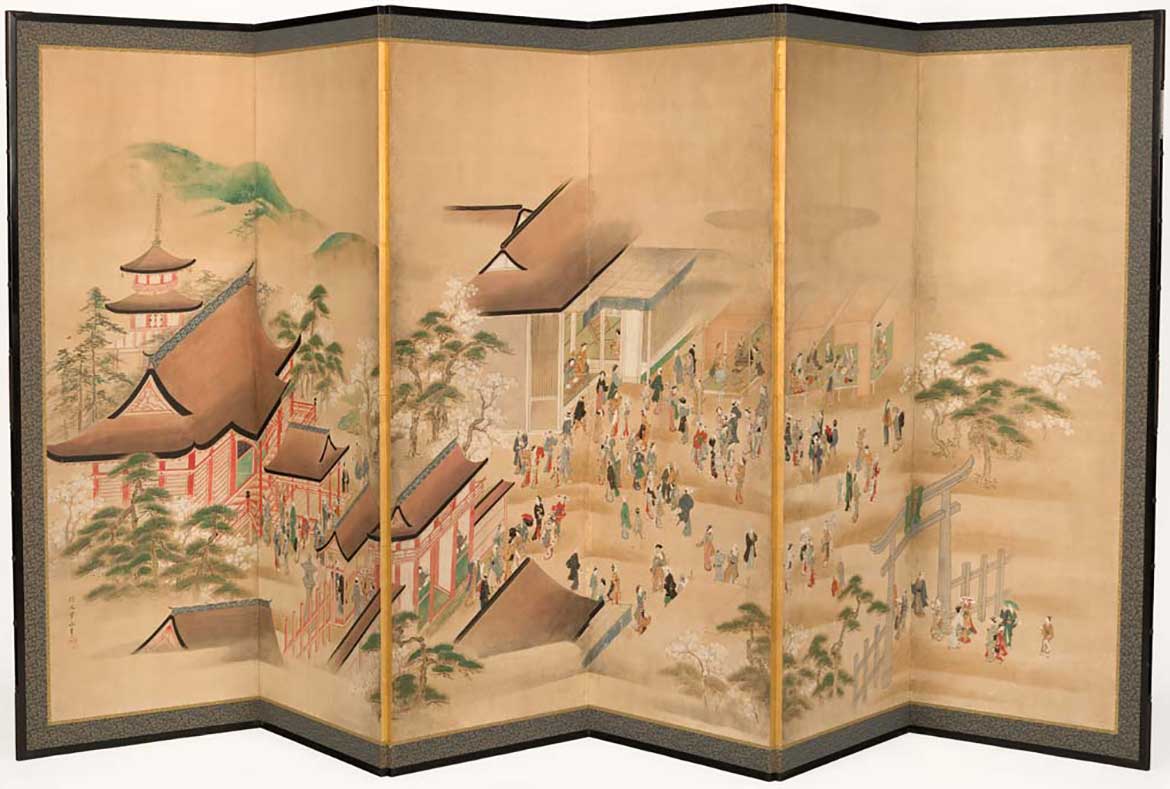

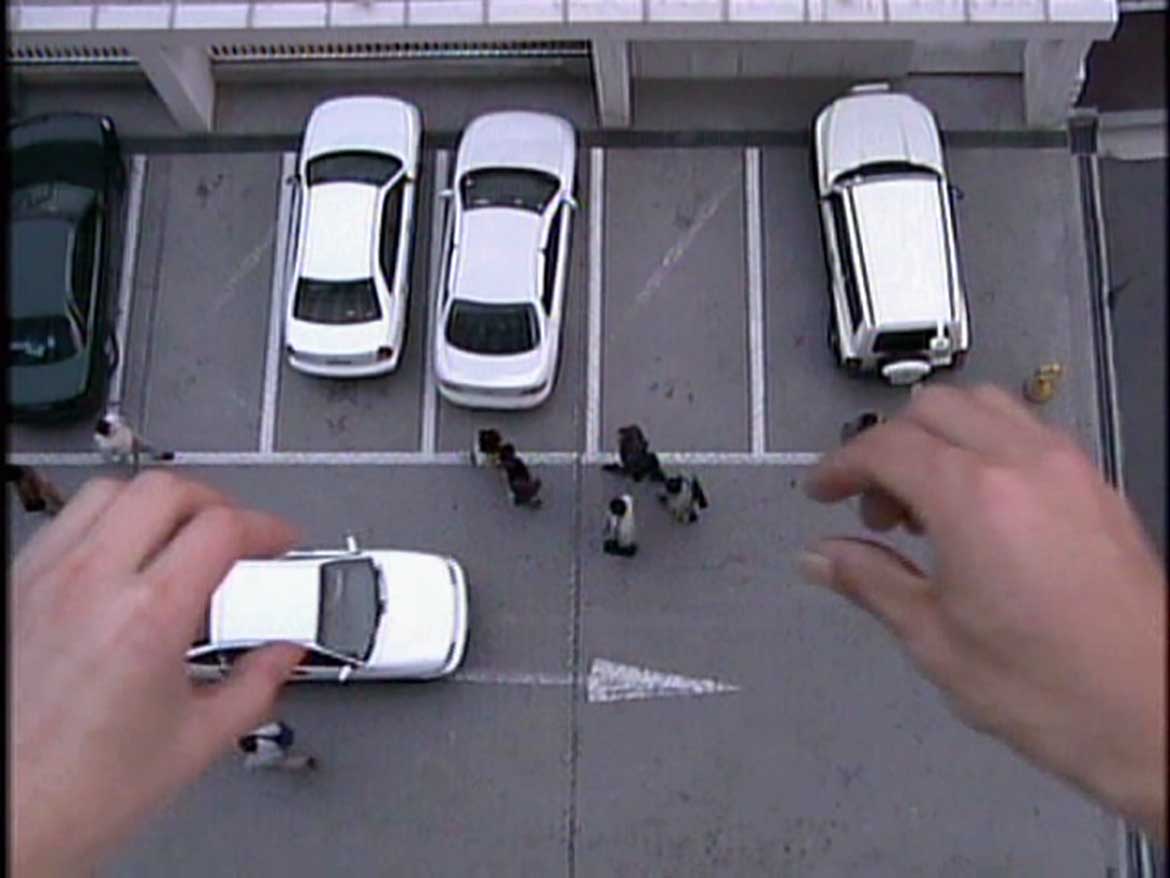

The famous 1968 photograph of Earth rising behind the moon, reproduced by artist Kota Ezawa, crystallised the precariousness and fragility of our small planet floating in a vast universe. This lack of a secure footing is represented in Chinese and Japanese landscape painting traditions, where unmoored mountain valleys appear to loom up in the picture plane, and interior scenes are glimpsed through breaks in the clouds. In the eighteenthcentury work Six-fold screen: Cherry blossom at Yasaka Jinja, Kyoto, artist Kawamata Tsunemasa has used a zigzagging planar recession to depict a Shinto shrine. This intense perspective is now ubiquitous to our experience of contemporary megacities. In 1 Parking 2001–02, Junebum Park films the street from such a sharp angle that it appears as if he is manipulating toy-sized cars below with his hands, articulating how the God’s-eye view is synonymous with power.

The increasing sophistication of mapping technology can give us a sense of control over our place in the world, but anyone who has been lost in the desert, at sea, or in a forest will have experienced how easily the scale of the natural world can overwhelm us. Eiichi Tanaka’s photographs of sand dunes on Fraser Island and Helda Groves’s abstract evocation of the ocean floor capture the immensity of the natural landscape and how it can fill our field of vision.

These works remind us how concepts of mapping change our perception of a place. Depending on the way we approach the world, we can read the cityscape or the natural landscape as teeming with information or reduced to abstraction. For instance, some viewers see George Tjungurrayi’s optical painting Untitled (Mamultjulkulnga) 2007 as a dizzying abstract pattern, where others see a detailed map that embodies a claypan site at Wilkinkarra (Lake Mackay) on the border of the Northern Territory and Western Australia. In Habitat, on loan from the artist, Taloi Havini uses a range of perspectives to create different associations with the land in and around the Panguna mine in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville. Succinctly referencing the mine’s history at the centre of a civil war, and as a site of ecological devastation, the scene is captured in sweeping overhead shots that evoke the view from a military helicopter.

Warfare is one of the main drivers of the growing sophistication of mapping technology. Just as aerial photography was refined during World War One, satellite imagery and drone footage dominate the recording of contemporary conflicts. Google Maps reference points are specified by an information architecture established by the US Government. In Propaganda (The red word is Iraq and the rest are saying: we can see you. Don’t use your nuclear or biologicals or chemical weapons!) 2009, Moataz Nasr stitches together images of a satellite, a map, and a human on the ground to bring into focus relationships that have become abstracted by technology. George Barber’s Freestone Drone 2013 is imagined from the point of view of an anthropomorphised drone, whose laconic self-reflection shows him being unresponsive to orders and flying without purpose. The work is a reminder that, while drones may be unmanned, they are still controlled by someone.

Dramatic changes in perspective can prompt us to rethink how we perceive the world. The limitations of representation and the political blinkers shaping our observations are addressed in video works by Nathan Pohio, Mike Parr and Peter Kennedy. In Landfall of a spectre 2007, Pohio mimics a large sea swell by using swaying movements while filming a lenticular print (in which two different images can be seen from different angles) of a colonial ship. Looping endlessly, this ghost ship appears to be forever adrift, unable to claim ground. As Parr pushes a Bolex 16mm camera over a hill, the screen is predominantly filled with blades of grass, with ‘visionary eruptions’ of the sky and the shaky horizon.2 Under such extreme conditions the camera is unable to focus, signalling that, like human vision, there are limits to what it can see. Both of these works create a sense of destabilisation, using the metaphor of vision to shake our assumptions.

The artworks in this exhibition reflect on the way that contemporary discussions about vertical perspective have a precedent in many aesthetic traditions.3 Bringing together a broad range of artworks — videos, paintings and works on paper from contemporary and historical periods, some of which are on loan from the artists — this exhibition connects human vision, mapping and surveillance to encompass broader aesthetic histories and ways of conceptualising the landscape.

Ellie Buttrose is Associate Curator, International Contemporary Art, QAGOMA

Endnotes

1 See Paul Virilio, War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception, trans. Patrick Camiller, Verso, London and New York, 1989.

2 Mike Parr, in conversation with Stephen Jones, recorded 26 August 2010, quoted in ‘Pushing a camera over a hill: Mike Parr’ in Scanlines: Media Art in Australia Since the 1960s, http://scanlines.net/object/pushing-camera-over-hill, accessed May 2017.

3 Engaging examples include Stephen Graham, Vertical: The City from Satellites to Bunkers, Verso, London and New York, 2016; and Grégoire Chamayou, Drone Theory, trans. Janet Lloyd, Penguin Books, London, 2015.

Know Brisbane through the QAGOMA Collection / Delve into our Queensland Stories / Read more about Australian Art / Subscribe to QAGOMA YouTube to go behind-the-scenes

‘Limitless Horizon: Vertical Perspective’ included a film- and video-screening program, and an array of artistic approaches that represent the landscape from above / Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) / 26 August 2017 – 25 March 2018

Featured image detail: Kota Ezawa’s Earth from moon 2006

#QAGOMA