Our culture — its art, music, theology and techno-science — is filled with the promises of monsters, that is to say, the irreverent energy of those who deviate from prescriptive normality.1

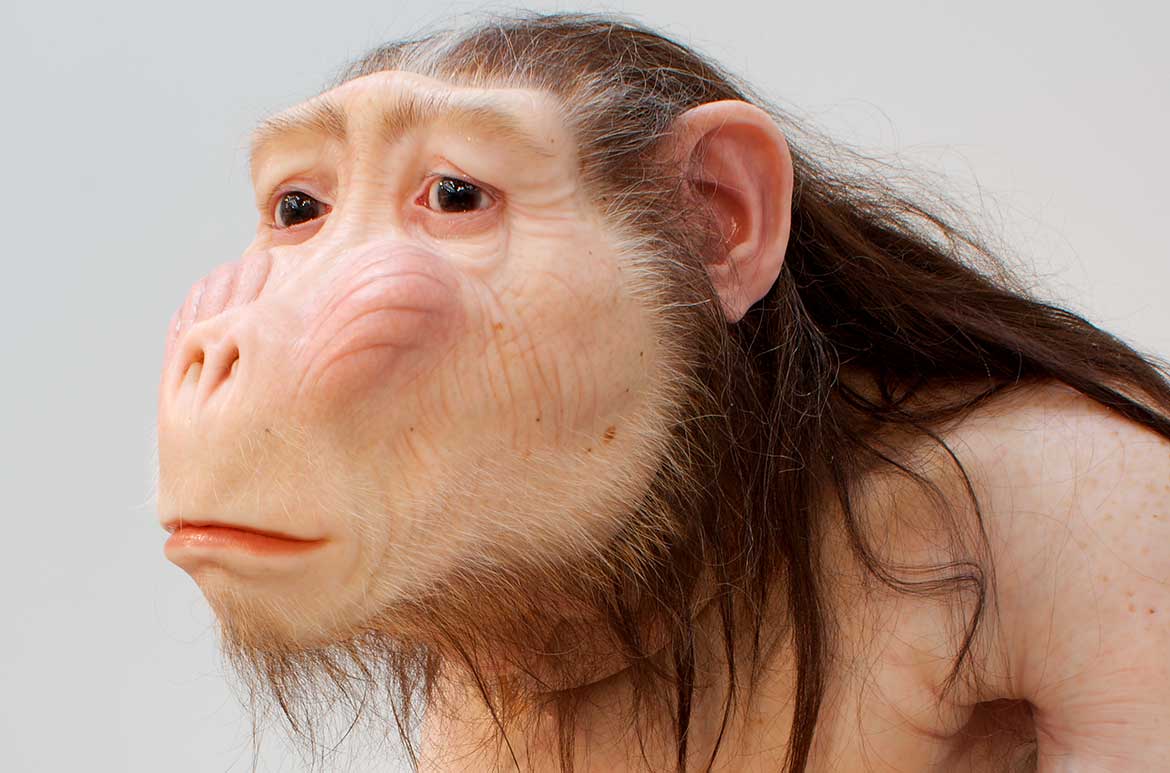

Known for her imaginative lifelike creatures, visit ‘Patricia Piccinini: Curious Affection‘ at GOMA until 5 August 2018, and ponder our place in a world where advances in technology are challenging the boundaries between human and monstrous hybrid creatures.

The connotations of that very term — monsters — however, tell a significant tale about our collective relationship to those who are otherwise embodied, both anthropomorphic — having human characteristics, and animal. Considered ‘other’, it is as if monstrous, non-human, animal and hybrid others inhabit a specific dimension that endows them with exceptional imaginary and metamorphic powers. They are both less-and-more than human, and other-than human at the same time.

Connection and empathy are at the heart of my practice. My creatures are imaginary beings that are almost possible. They are not always traditionally beautiful, but they have a beauty and an honesty within them. They are more vulnerable than threatening.

Patricia Piccinini

Piccinini’s monstrous bodies blur the distinction between normal and pathological, self and other, human and non-human, and, in this capacity, they are a privileged site of phantasmic projection. Their influence on the cultural imagination is far-reaching: hybrid, monstrous bodies are cast in the mode of a familiar, yet threatening, otherness — a quasi-kin. They embody ontological impropriety. As objects of simultaneous wonder and fear, admiration and disgust, they cause a disturbance in the status quo, evoking a mixture of fascination and loathing. Whatever the response, they are culturally produced as sensational objects of visual display.

There is also a paradoxically reassuring quality about them: their hybrid, monstrous bodies have already undergone a catastrophic mutation and have survived. Most people go through life dreading that they will have to confront a traumatic experience, but monsters already have. They embody both the trauma and the act of overcoming; having passed their test in life, they count as existential aristocrats.2 Their resilience grants them a cathartic function in relation to those — especially humans — who are still fearfully anticipating a blow.

Patricia Piccinini highlights her favourite works

The artist challenges us to review our preconceived ideas and socially enforced relationships with the otherwise embodied. This critical process starts by questioning the very cultural repertoire and mental habits that have structured our visual, cognitive and affective relationships with these others.

Piccinini’s hybrid, monstrous creatures return our gaze, they look back at us and thus undo the consumeristic objectification of their otherness. They also look into us, with eyes full of compassion and understanding. Their intensity explodes the boundaries between human normality and its others. They stand in their plenitude, looking at our lack. Although it is tempting to take this remark as a humanisation of their gaze and their moral fibre, it would also be condescending to attribute human qualities, as if these traits were inherently superior. It is rather the case that Piccinini’s others transcend the binary divides altogether and come to exist in a continuum with a multitude of human and non-human others. In so doing, they challenge and shift boundaries. Their relational power induces a trans-species form of care, while their empathic force expresses a posthuman relational ethics.

Read more on our blog / Subscribe to YouTube to watch behind-the-scenes footage and exclusive interviews / Buy the publication

Patricia Piccinini, Australia b.1965 / Big Mother 2005 / Silicone, fibreglass, polyurethane, leather, human hair; ed. 2/3 + 1 AP / 175cm (high) / Gift of S Angelakis, John Ayers, Candy Bennett, Cherise Conrick, James Darling AM and Lesley Forwood, Rick Frolich, Frances Gerard, Patricia Grattan French, Stephanie Grose, Gryphon Partners Advisory, Janet Hayes, Klein Family Foundation, Edwina Lehmann, Ian Little, David and Pam McKee, Dr Peter McEvoy, Hugo and Brooke Michell, Jane Michell, Paul Taliangis, Michael and Tracey Whiting and anonymous donors through the Art Gallery of South Australia Contemporary Collectors 2010 / Collection: Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide / © The artist

Endnotes

1 Donna Haraway, ‘The promises of monsters: A regenerative politics for inappropriate/d others’, in Lawrence Grossberg, Cary Nelson and Paula A Treichler (eds), Cultural Studies, Routledge, London and New York, 1992.

2 Diane Arbus, Diane Arbus, Millerton, New York, 1972, p.3.

Professor Rosi Braidotti was born in Italy and grew up in Australia, where she received a First-Class Honours degree from the Australian National University in Canberra in 1977. She went on to receive a degree in philosophy from the Sorbonne in Paris in 1981. She has taught at the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands since 1988, when she was appointed as the founding professor in women’s studies. In 1995, she became the founding Director of the Netherlands research school of Women’s Studies, a position she held until 2005. She was also founding director of the Centre for the Humanities from 2007 until 2016. Braidotti is a pioneer in European women’s studies and her fields of interest include social and political theory, cultural politics, gender, feminist theory and ethnicity studies.

Feature image detail: Patricia Piccinini’s Big Mother 2005

Edited extract from ‘Affirmation and a passion for difference: Looking at Piccinini looking at us’. Read the full essay in Patricia Piccinini: Curious Affection.

#PiccininiGOMA