‘My Country, I Still Call Australia Home: Contemporary Art from Black Australia’ examined strengths within the Queensland Art Gallery collection of Indigenous art and recognised three main central themes: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander versions of history; responses to contemporary politics and experiences; and connections to place. These themes are expressed in the three main Gallery spaces as the visual chapters: ‘My history’, ‘My life’ and ‘My country’.

Gordon Hookey ‘Blood on the wattle, blood on the palm’

The works presented in ‘My life’ show the crucial engagement of artists of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander heritage with contemporary politics. Worldwide, agitation for sovereignty, self-determination, justice, freedom and social and legal equality has traditionally flowed from street movements into the arts. This is equally true of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander protest and political movements in Australia.

The recurring shame of Aboriginal deaths in custody features prominently in the exhibition. Across Australia, the first meetings between Aboriginal people and the police were often facilitated at the end of a gun barrel. Mounted police and their ‘native’ recruits were used to clear the frontier of ‘problem’ Aboriginal populations; ‘to disperse’ became a euphemism for killing entire groups of people. Today, ‘to defy’ has become a common response from Aboriginal people who still bear the scars of a historically abusive relationship. Gordon Hookey’s painting Defy 2010 bears witness to this history while acknowledging the contemporary reality that little has changed.

This strained relationship shows scant sign of healing, with alarmingly frequent reports of police assaults on Aboriginal people and continued deaths in custody, despite a 1990 Royal Commission into the matter. The issue was brought to a head by the death of Daniel Yock, an 18-year-old Aboriginal man and well-known dancer who was killed by police in West End, Brisbane, in 1993. Vincent Serico’s Deaths in custody was made that year and encapsulates the mournful feeling attached to this era. It refers to a friend who took his own life in jail after a series of visions. In it, a mopoke owl — a reference to the totemic spectre of death — watches over the jail cell.

Perhaps most famously, in 2004 an Aboriginal man died while in police custody on the Queensland Aboriginal community of Palm Island. The ensuing political circus tore the heart out of the proud community. Vernon Ah Kee’s Tall Man 2010 pieces together amateur video from the day a tipping point was reached following the report that this death was the result of an accident. This flashpoint is one that is just moments from exploding in nearly every Aboriginal community. Gordon Hookey’s Blood on the wattle, blood on the palm 2009 (illustrated) stands in solidarity with the leaders of the resistance or ‘riot’ that ensued on Palm Island. His painting is fuelled by anger at the fact that the only people jailed after the killing of one of their own are Aboriginal. Hookey’s work references Bruce Elder’s controversial book Blood on the Wattle: Massacres and Maltreatment of Aboriginal Australians Since 1788 8 and recalls Henry Lawson’s iconic poem ‘Freedom on the Wallaby’, penned to galvanise the Barcaldine Shearer’s Strike of 1891:

So we must fly a rebel flag

As others did before us.

And we must sing a rebel song,

And join a rebel chorus.

We’ll make the tyrants feel the sting

O’those they would throttle;

They needn’t say the fault is ours

If blood should stain the wattle.9

Hookey connects this stand to the historical mistreatment of Aboriginal people and to universal struggles against tyranny.

Life in all Aboriginal communities is complex. There are still struggles with the legacy of colonial conflicts and policies, yet life continues to be far richer than as reported in mainstream media. Community life is an important aspect of ‘My life’. Lama Lama painter Adrian King reminisces about times of happiness in the Lockhart River community and the unifying effects of football competitions, as well as his return to Wenlock Outstation on his own country; Bindi Cole illuminates the story of the ‘Sistagirls’ or ‘Yimpininni’ of the Tiwi Islands, bringing just one of countless diverse Indigenous experiences to light; Christian Thompson’s sinister ‘Black Gum’ 2008 series contrasts Australia’s infatuation with native flora with ideologies that correlate Aboriginal people with flora and fauna, not humanity. The black ‘hoodie’ that the artist dons alludes to the growing numbers of disaffected Aboriginal youths for whom the gap between their realities, and those of the general Australian populace, continually widens.

Importantly, the exhibition also examines issues of racism in three realms of contemporary Australian society — sport, music and art — which are often theatres for racial tension, despite Indigenous Australians making significant impacts.

Ron Hurley ‘Bradman bowled Gilbert’

Ron Hurley’s Bradman bowled Gilbert 1989 (illustrated) unites the contrasting lives of two depression-era sporting heroes — Donald Bradman and Eddie Gilbert. Even in an impoverished era, Australians paid handsomely to watch these enormously popular sportsmen play. But on one day in 1931, Gilbert, considered one of the world’s fastest ever bowlers, did the unimaginable. He bowled Bradman for a ‘duck’, which led to controversy over Gilbert’s bowling action.10 Soon the Queensland Cricket Association instructed the Protector of Aborigines in Queensland to ‘return Gilbert to the Cherbourg Aboriginal Mission at once’. He was scarcely heard of again until news of his death emerged in 1978 after he had spent the preceding 29 years in a Brisbane psychiatric hospital.11

From the world of music, Gordon Bennett’s If Banjo Paterson was black 1995 imagines what the life of Australia’s most famous poet might have been had he been born Black. Musicians in the pre-modern era were marginalised while their music was appropriated. Bennett connects this practice to the appropriation of designs from First Nation and traditional societies by an art world intent on liberating them from their original contexts and mitigating meaning until a modern art design remains. Bennett’s cubist-inspired banjo sculpture takes aim at the appropriation of African traditions by one of Europe’s most important art movements, while his mirror-lined box of ‘Coon Sticks’ (a confectionary produced in Melbourne in the early 1900s) is:

‘a metaphor for complexity and the indescribable (with language) “reality” of the human mind with its constant flow of thoughts, knowledge, memories of the past, experience of the present and imaginations of a better future’.12

Richard Bell considers the same history in Bell’s Theorem (Trikky Dikky and friends) 2005, but he goes one step further, listing the names of visual artists he believes have appropriated Aboriginal designs or misrepresented the art and culture of Aboriginal people in their works.

One of the most important social movements toward positive change in recent decades has been the Reconciliation Movement, which gained momentum in the wake of then prime minister Paul Keating’s 1992 ‘Redfern Address’, perhaps the most significant and stirring oration concerning Indigenous people and issues by any Australian politician. In the address he asked Australians to imagine themselves in the shoes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in a particularly poignant passage:

. . . it might help us if we non-Aboriginal Australians imagined ourselves dispossessed of land we have lived on for 50 000 years — and then imagined ourselves told that it had never been ours . . . Imagine if ours was the oldest culture in the world and we were told that it was worthless. Imagine if we had resisted this settlement, suffered and died in the defence of our land, and then were told in history books that we had given up without a fight . . . Imagine if we had suffered the injustice and then were blamed for it . . . It seems to me that if we can imagine the injustice then we can imagine its opposite. And we can have justice.13

Richard Bell’s I didn’t do it 2002 looks at the popular backlash against this move toward social change and equality. Unfortunately, not all Australians were touched by Keating’s words. Instead, collective amnesia and forfeiture of responsibility for Australia’s colonial history dogged this campaign, and continues to tarnish political, social and historical debates surrounding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and issues. Bell’s I didn’t do it takes aim at this ideology, explaining that, to some extent, every Australian is living off the wealth of colonisation and the deprivations of Australia’s First Nations.

Former prime minister Kevin Rudd’s ‘Apology to Australia’s Indigenous Peoples’ was another move toward recognising the hurt to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, brought about by past policies and practices:

We apologise for the laws and policies of successive parliaments and governments that have inflicted profound grief, suffering and loss on these our fellow Australians. We apologise especially for the removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families, their communities and their country . . . For the pain, suffering and hurt of these Stolen Generations, their descendants and for their families left behind, we say sorry.14

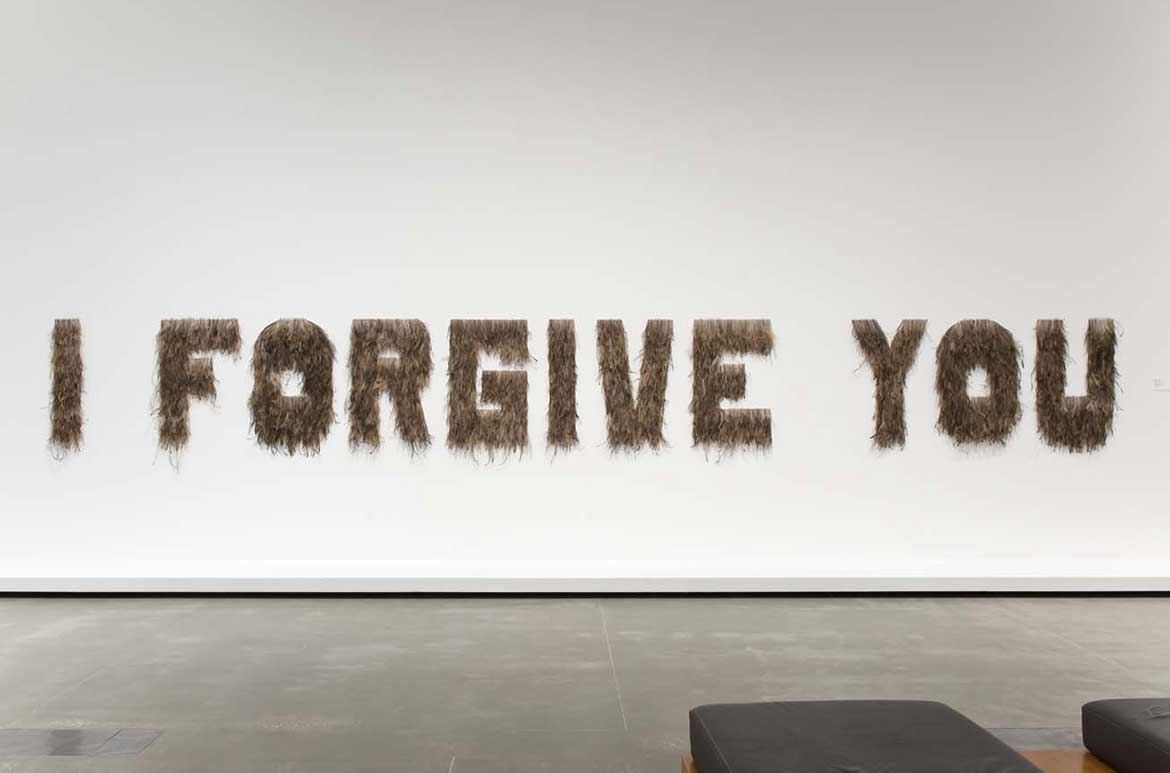

Bindi Cole ‘I forgive you’

Bindi Cole’s brave work I forgive you 2012 (illustrated) was created in response to this apology, and to events that have affected her family for generations, such as the government- mandated forced removal of mixed-race children from Aboriginal families.

In February 2013, the fifth anniversary of the Apology, and on the passing of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Recognition Bill 2012,15 Prime Minister Julia Gillard commented that:

. . . there is no record of any Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander person taking part [in building our national charter] . . . No mention of their dispossession, their proud and ancient cultures, their profound connection to the land or the unhealed wound that even now lies open at the heart of our national story . . . No gesture speaks more deeply to the healing of our nation’s fabric, than amending our nation’s founding charter . . . We are bound to each other in this land and always will be. Let us be bound in justice and dignity as well.16

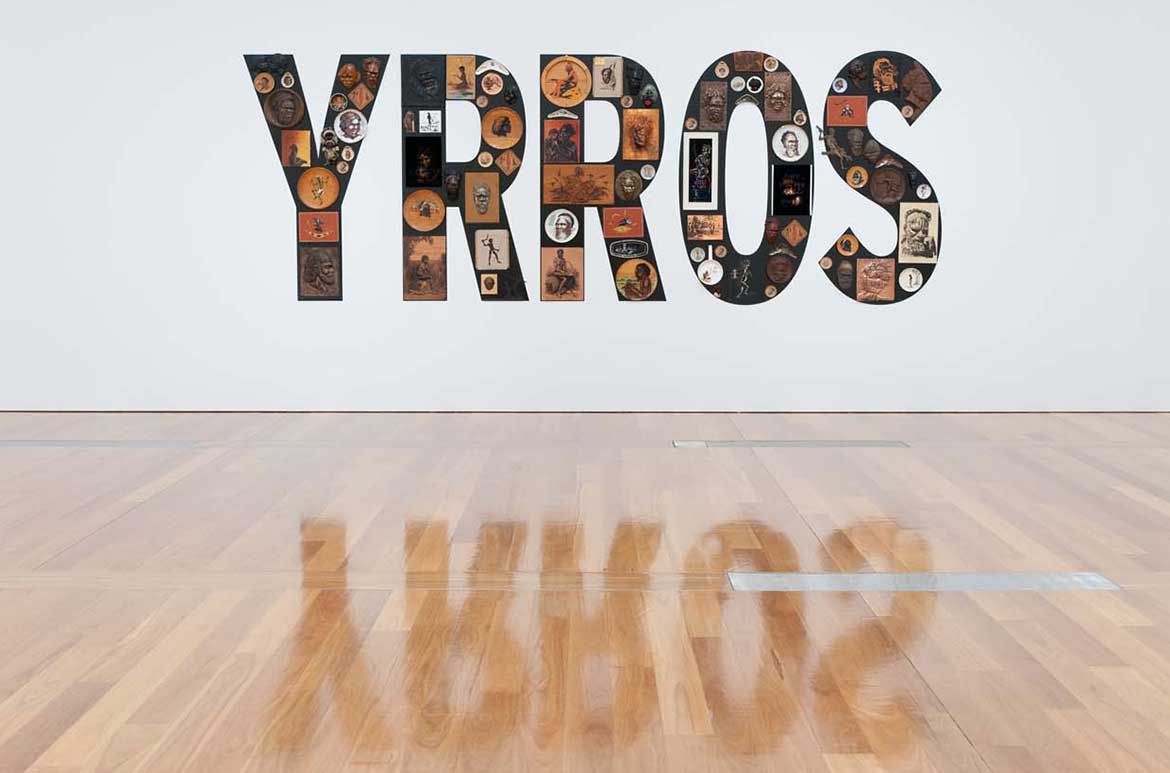

Tony Albert ‘Sorry’

Despite these hard-won victories, Bell, Albert and many other Aboriginal people view these speeches and apologies as piecemeal or as an emotional sideshow distracting people from the ultimate goals of self- determination, land rights (over Native Title) and recognised sovereignty for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. In recent years, Albert’s Sorry 2008 (illustrated) has been installed backwards to highlight this point.

Bruce McLean is former Curator, Indigenous Australian Art, QAGOMA

Extract from the ‘My Country, I Still Call Australia Home: Contemporary Art from Black Australia’ exhibition catalogue essay ‘This land is mine / This land is me’

Endnotes

8 Bruce Elder, Blood on the Wattle: Massacres and Maltreatment of Australian Aborigines Since 1788, New Holland Publishers, Frenchs Forest, NSW, 1988.

9 Henry Lawson’s ‘Freedom on the Wallaby’ was first published by David A Cumming in the Brisbane newspaper, The Worker, 16 May 1891, p.8.

10 The Queensland Cricket Association president rejected the ensuing claims that Gilbert had a suspect bowling action, saying that ‘every umpire whose business it was to decide the question passed him’. However, controversy about Gilbert’s bowling action abounded, no doubt contributing to a slump in form for a man many Queenslanders saw as a hero. There were suggestions that the colour of his skin obscured a ‘chucking’ action. Sunday Mail, 3 September 1995, p.1 by John Hay.

11 For more on Eddie Gilbert see Mike Coleman and Ken Edwards, Eddie Gilbert — The True Story of an Aboriginal Cricketing Legend, ABC Books, Sydney, 2002.

12 Bennett, in a letter from the artist, to Sue Smith, art writer for the Courier-Mail, 11 May 1995.

13 For more on the Redfern Address see australianscreen/ National Film and Sound Archives: http://aso.gov.au/ titles/spoken-word/keating-speech-redfern-address/ and http://aso.gov.au/titles/spoken-word/keating- speech-redfern-address/notes.

14 The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Recognition Bill 2012 aims to begin the process to formally recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the constitution.

15 Former prime minister Kevin Rudd, Apology to Australia’s Indigenous Peoples http://australia.gov.au/ about-australia/our-country/our-people/apology-to- australias-indigenous-peoples.

16 Eleanor Hall, ‘Recognition Act a step to constitutional change’ (ABC News/The World Today) http://www.abc. net.au/worldtoday/content/2013/s3689301.htm.

‘This land is mine / This land is me’ is an extract from the 2013 exhibition catalogue ‘My Country, I Still Call Australia Home: Contemporary Art from Black Australia’ by Bruce McLean.

#QAGOMA

Very moving

Perhaps art will reach people’s hearts and minds in a way that words can not.

It was my last morning in Brisbane that I saw the exhibition My Country , I Still Call Australia Home: Contemporary Art from Black Australia. It was extraordinarily painful and often stunningly beautiful, so much so that I needed many breaks as I viewed the artworks. I had spent a few days at an interfaith conference called Engaging the Other and I thought any one of the artworks would work as a way of engaging the other. They spoke from within the Black experience to challenge the white normality in way that reached into the psyche and disturbed the comfort that even those of us who like to think we are critical or enlightened. Each of these works seeks in different ways to unbalance the white viewer. Often this is done by alienating us from narratives of white history. Sometimes it seeks to render the reality of dispossession and alienation through sardonic reflections on white neurosis and loss or on the often baleful effects of colonial or religious oppression. Often it just works by creating a Black view as the norm. I just want to thank you for providing this very confronting and also very beautiful experience.