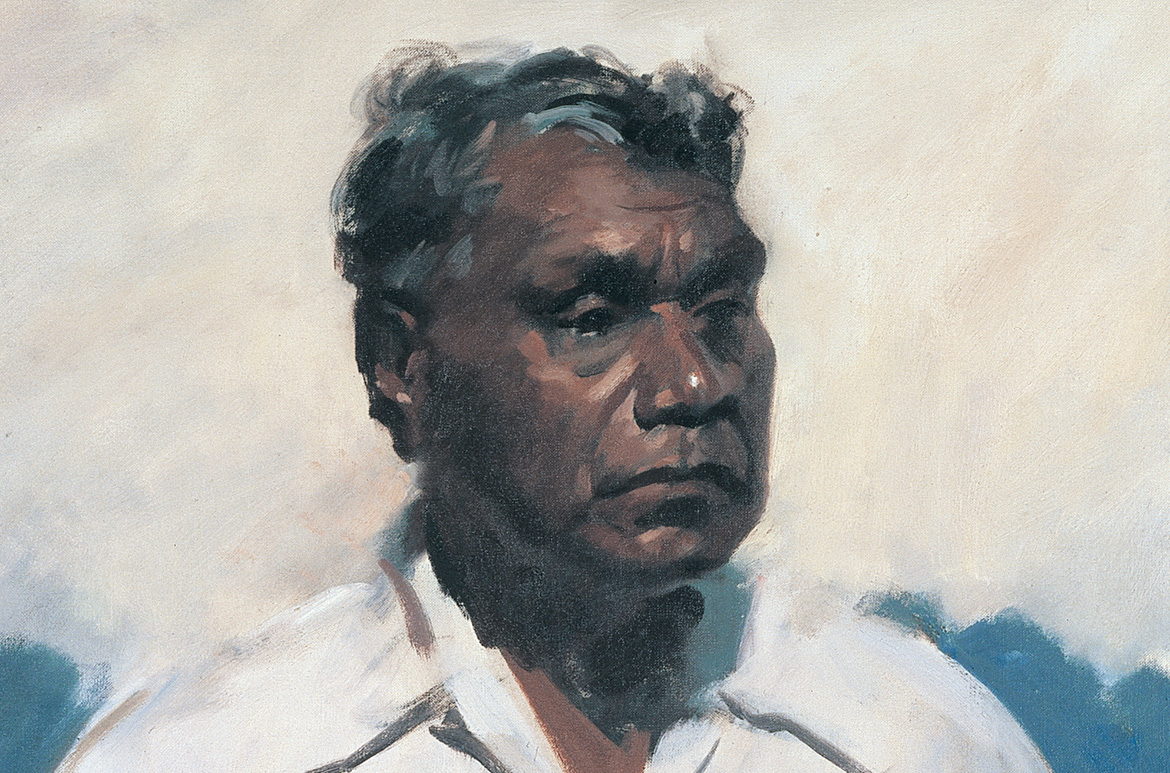

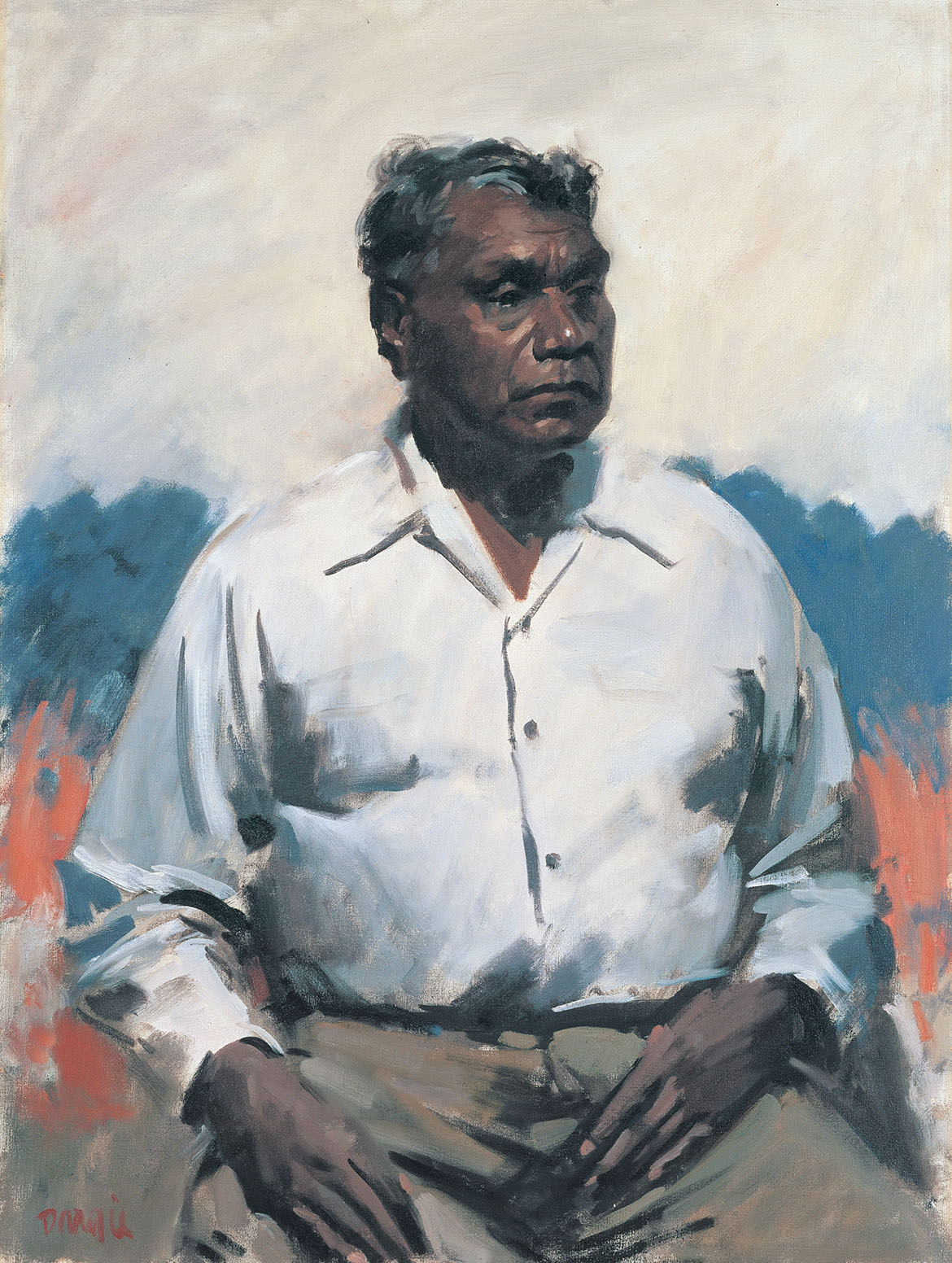

A conventional portrait — a seated half-figure painted from life — which is disrupted by the subject’s race. In mid-twentieth-century Australia, Indigenous people had rarely figured in a genre that confirmed the status of ‘elder statesman’ upon its (mainly male) subjects. William Dargie’s Portrait of Albert Namatjira 1956 (illustrated) has subsequently become the most identifiable image of the artist, familiar yet reserved. His facial expression is withdrawn, his eyes look away, and the head is likewise turned from frontal scrutiny to form a three-quarter profile.

William Dargie ‘Portrait of Albert Namatjira’

Namatjira’s self-contained composure resists revelations of character or psychological insights, yet there is a temptation to read the sombre face as a reflection of his own state of mind concerning recent events such as the death of his father and the denial of his rights as a non-‘citizen’.1 However, there is no sense of Namatjira as a victim, for the values implied in a commemorative portrait presuppose a viewer who will contemplate the subject at a respectful distance. Within the conventions of European tonal portraiture, there is a subdued drama between the open-necked white shirt and the skin it exposes, between the large, bulky torso and the long, fine-boned hands.

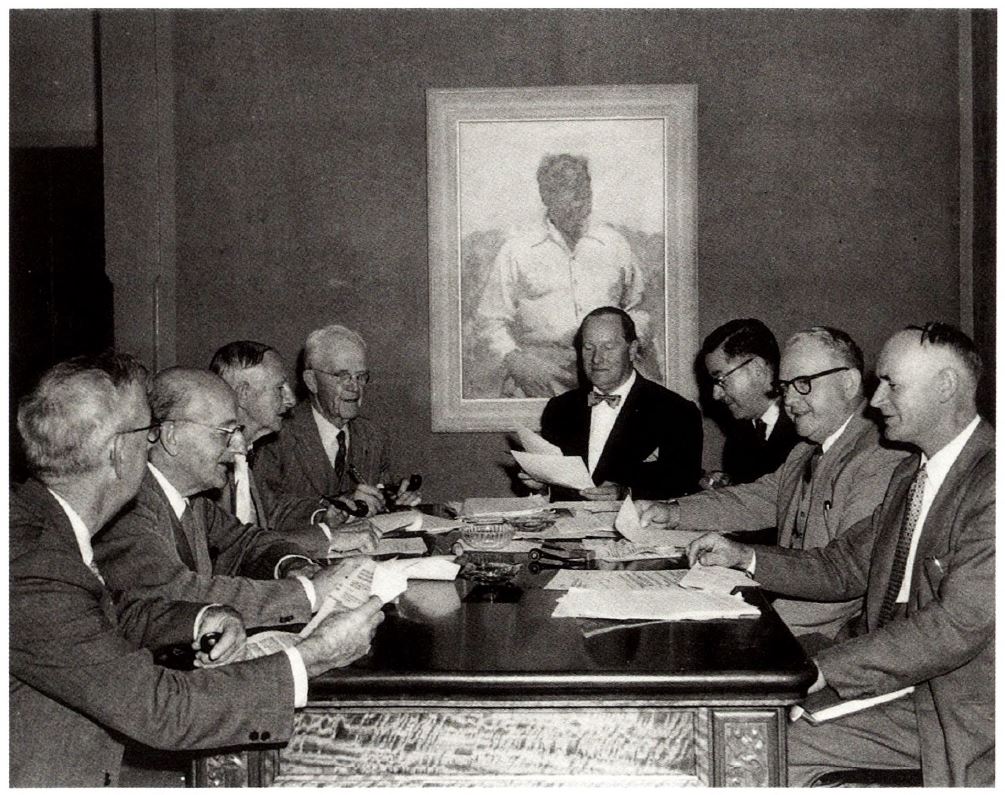

Sir William Dargie was the favoured ‘court’ painter of the Robert Menzies era (Menzies served as Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1939 to 1941 and again from 1949 to 1966), his name synonymous with the portrayal of captains of industry, knights of the academy and society dames.2 He was both a skilled adviser and confidant to government, serving for over twenty years on the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board, and a popularly acclaimed practitioner, eight times winner of the Archibald Prize for portraiture in Australian art.

This portrait was his last Archibald win and was acquired the following year by the Queensland National Art Gallery (now QAGOMA), for ‘the highest [price] ever paid by the Gallery Trustees for a painting’ — a fact that drew national media attention to the artist:

William Dargie, whose portrait painting earns him more than many top-level business men make and who looks more like a business man than an artist.3

RELATED: Albert and Vincent Namatjira

RELATED: Albert Namatjira

A portrait by Dargie, who was then at the pinnacle of his achievement having recently painted the Queen for the Commonwealth, represented the confirmation of great social value in 1950s Australia. Such portraiture seems now to occupy such a narrow place in our culture that one would imagine that his name could be left undisturbed on the walls of war memorials and boardrooms. Yet how do we reconcile the sense of a moribund practice when confronted by this singularly impressive portrait of Namatjira which challenged the attitudes of his contemporaries?

In painting a fellow painter there is frequently a desire to match or invoke the other’s work, Dargie does not compete with his subject. In the early 1950s he had painted with Namatjira in Central Australia several times and a mutual respect developed between Dargie the oil painter and Namatjira the watercolourist. Dargie recalls:

We had agreed that he was going to sit for me. I liked his natural rebelliousness.4

In the portrait there are no signs of Namatjira’s own work or tools of trade, the painter’s hands lie unused in his lap. Only a vague reference is made by the loosely brushed bands of orange and blue behind the figure, alluding to the colours that Namatjira used to represent his country. In fact, the background is the least convincing aspect of the painting, like a flat stage-set at odds with the interior lighting that highlights his features.

Namatjira was ten years Dargie’s senior and both were household names of the time. In November 1956 they were photographed in a Sydney art supply shop holding tubes of paint, and the press finally pursued Namatjira to Dargie’s studio where, half a dozen times over a fortnight, he had sat in the early mornings while Dargie worked on the canvas.

Dargie’s identity is eclipsed by his subject whose work continues to influence contemporary Indigenous culture and artists beyond his own community.

Edited extract by Ann Stephen from ‘Namatjira in the guise of an elder statesman: William Dargie Portrait of Albert Namatjira‘ in Brought to Light: Australian Art 1850-1965, Queensland Art Gallery, 1998.

Endnotes

1 In 1950 Namatjira bought land in Alice Springs. However, the Northern Territory government refused to allow transfer of the land title to him. In 1957 Namatjira was granted Australian citizenship by being excluded from the Northern Territory register of ‘full-blood’ Aboriginal wards. The following year he was imprisoned for supplying alcohol to Aborigines, who were not citizens. See Hardy, Megaw & Megaw (eds), Chapters XIX-XX.

2 Dargie: 50 Years o f Portraits, Gallery 499, Roy Morgan Centre, Melbourne, 1985.

3 Sydney Morning Herald, 15 May 1957, Adelaide News, 23 May 1957, amongst press clippings in acquisition file, Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane.

4 Sir William Dargie, telephone conversation with the author, 21 December 1996.

Delve deeper into the collection

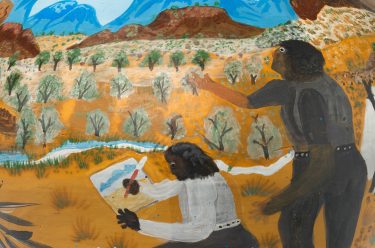

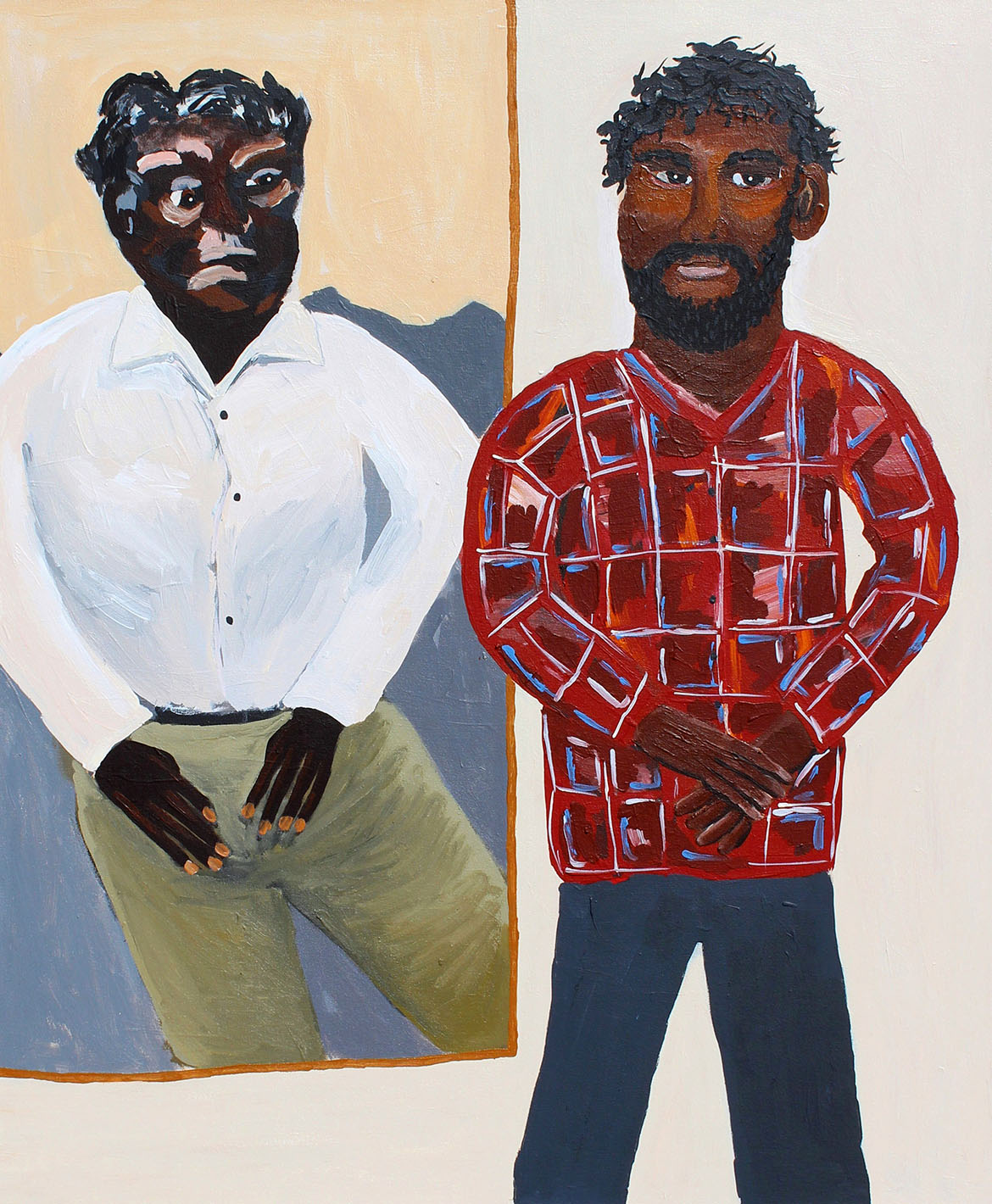

Albert and Vincent 2014 (illustrated) is the result of Vincent Namatjira’s visit to the Gallery to view Portrait of Albert Namatjira 1956. Previously Vincent had seen the work only as a reproduction, and as a portrait painter whose work is often inspired by the image and cultural impact of his grandfather, he had a strong desire to view the work in person. Visiting the Gallery Vincent sketched the portrait of his grandfather, taking his sketches home and finishing the work there. He imbued it with the conflicting emotions so often evoked by Albert’s stories, giving the portrait a celebratory feel while retaining a sombre sensibility.

RELATED: Albert and Vincent Namatjira

Vincent Namatjira ‘Albert and Vincent’

Acknowledgment of Country

The Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land upon which the Gallery stands in Brisbane. We pay respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander elders past and present and, in the spirit of reconciliation, acknowledge the immense creative contribution Indigenous people make to the art and culture of this country.

It is customary in many Indigenous communities not to mention the name of the deceased. All such mentions and photographs on the QAGOMA Blog are with permission, however, care and discretion should be exercised.

Featured image detail: William Dargie Portrait of Albert Namatjira 1956

#QAGOMA