The 10th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT) opening 4 December 2021, presents an opportunity to reflect on the courses that art has taken over the three decades of the APT’s existence. The exhibition ‘Reality and Invention: Contemporary Asian Art’ presents one possible framework for interpreting this history, from the perspective of the emergence of realism as a defining artistic strategy of the period.

RELATED: Delve into the Asia Pacific Triennial

From Chinese cynical realism to Japanese Neo-Pop and Indian figurative–narrative art, the emergence of realism in contemporary Asian art — underway since the 1980s — manifested as a diversity of innovative responses to seismic shifts. By the time the first APT opened in the early 1990s, the Cold War had come to an end, and the subsequent decline in influence of the traditional superpowers, in concert with economic booms in East and South East Asia, challenged conceptions of national and regional identity. Calls for political participation engendered transitions to civilian democracy in some contexts and authoritarian crackdowns in others, while urbanisation, consumerism and the dawning information age added powerful new social forces to an already dynamic mix. As the Queensland Art Gallery’s then deputy director, Caroline Turner, put it, ‘Sometimes artists have to confront changes which are bewilderingly rapid and, in a myriad of changing focuses, make sense out of contemporary events’.1 Unlike the Western European Realism movement of the nineteenth century, the various realisms that manifested in Asia could not be narrowly unified as a specific style or approach to subject matter, but rather, what Japanese curator Masahiro Ushiroshoji described in 1994 as ‘realism as an attitude’.2 In response to new realities, artists began to explore new artistic forms such as installation and performance, new materials that reflected the texture of everyday life, and the expression of new subjectivities. As society changed, so did art.

‘Reality and Invention’ accordingly takes in engagements with political and social structures, religion and spirituality, gender and sexuality, and the increasingly complex array of influences on lived experience presented by globalisation, all rendered in arresting and innovative forms. Though the exhibition focuses on the period between the late 1980s and the early 2000s, when Asian artists rose to international prominence, it also includes anticipations of the realist attitude from earlier decades as well as its persistence in more recent work.

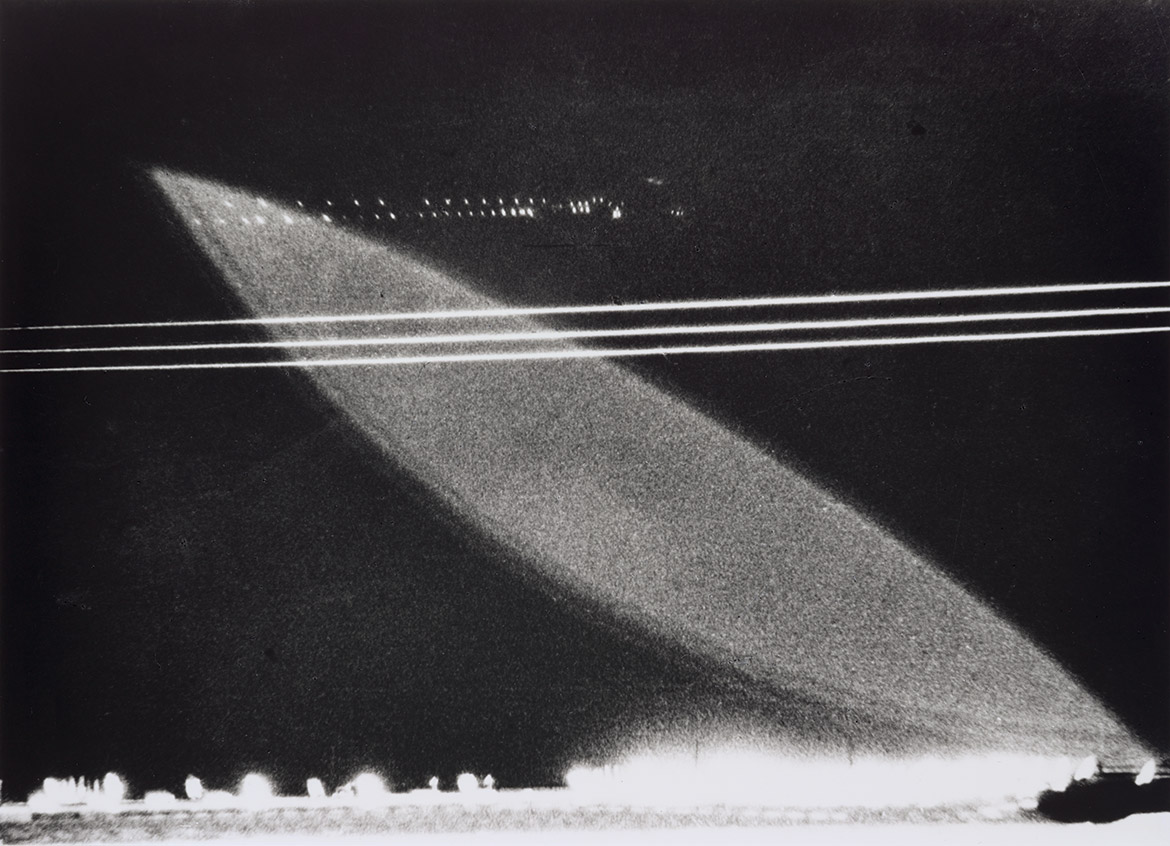

Examples by earlier generations of artists include a swirling canvas by Indonesian modernist Affandi (illustrated); two decades of photographic work by Nasreen Mohamedi (illustrated), abstracting lines found in shadows, sand and road markings into graphic constructions; and a highly significant early example of the figurative–narrative approach of Mohamedi’s fellow mentor at India’s Baroda School, Bhupen Khakar. Mao Ishikawa’s photographic portraits of marginal workers such as nightclub dancers and dockyard labourers at play in 1970s and 80s Okinawa are complemented by Ismail Hashim’s lovingly photographed and handcoloured Seats of bicycles of Penang port labourers 1993. These works set the tone for a widespread investment in the details of daily life at a point of transformation, and for the search for new modes of expression capable of honouring fleeting moments while keeping pace with social change.

Queensland Art Gallery Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © FX Harsono

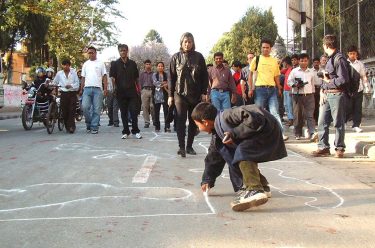

Dedi Eri Supria and FX Harsono were participants in Indonesia’s politically engaged Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru, or New Art Movement, which sought an ‘aesthetics of emancipation’ to transcend binary arguments of Western and Eastern culture. Supria developed an intricate photorealistic painterly technique and epic compositional style, represented here by his Labyrinth 1987–88 (illustrated), which reflect the ugliness and chaos of urban life through metaphor and mass-cultural quotation. A photographic installation by Harsono (illustrated) presents a sequence of hands spelling out the word ‘democracy’ in universal sign language, which can then be interactively translated into text by the viewer using ink stamps, suggesting art as a way of breaking through silence for those without voices. This invocation of democracy as an idealised political system and as an imperfect reality is echoed in locally focused paintings by Thailand’s Vasan Sitthiket and the Philippine artist collective Sanggawa (illustrated), which are by turns searing and satirical. Sharon Chin provides a more recent take, sewing patterns of weeds onto opposition party flags collected from the 2013 Malaysian election.

Feminism is a major thread in ‘Reality and Invention’, reflecting the centrality of women’s participation in broader political movements and in struggles over ethnic identity and gender roles amid shifting national and economic systems. Brenda Fajardo and Yun Suk-nam were both participants in broadbased intersections of art and social activism: the Philippines social realism movement of the 1970s and the South Korea’s prodemocracy- aligned minjung misul (people’s art) of the 1980s, respectively. Fajardo’s works on paper draw on Tarot to present alternative readings of Filipino history, while Yun’s striking installation Pink sofa 1996 (illustrated) allegorises female experience though a luxurious piece of furniture riven with knife-like spikes. Lee Bul, Emiko Kasahara and Mika Yoshizawa, on the other hand, speculate on women’s roles in possible futures, through Bul’s delicate ceramic feminine cyborg parts, Kasahara’s sculptures of embryonic human genitalia, and Yoshizawa’s slick, gestural painterly evocation of the gendered product design and popular culture.

Like Kasahara and Yoshizawa, Yasumasa Morimura and Shinro Ohtake are often associated the Japanese New Wave of the 1980s, which took their generation’s immersion in consumer culture, along with a fervent experimentalism, as its point of departure. Morimura’s photomontage Blinded by the light 1991 (illustrated), which parodies Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s iconic 1568 Parable of the Blind, shows the artist himself playing a cast of character archetypes of aspects of Japan at the height of its economic power. Ohtake, active since the late 1970s, is represented by a more recent work in his well-established style — a dense collage of cut-out photographs and other found materials, punctuated with burst of iridescent colour to create an intense visual field. By the 1990s, the New Wave had evolved into the even brasher forms of Tokyo Neo-Pop, almost indistinguishable from the field of popular culture itself, typified by Takashi Murakami’s monumental painting And then, and then and then and then and then 1994.

Neo-Pop finds a counterpart and a contemporary (albeit under different social conditions) in cynical realism — a heavily ironic take on the coexistence of Chinese communist ideology and free-market restructuring. In ‘Reality and Invention’, it provides a framework for showcasing selections from QAGOMA’s collection of contemporary Chinese painting. This includes Liu Xiaodong’s early experiment in the expressive power of figuration, the fully realised 90s cynical realism of magnificent paintings by Zhang Xiaogang and Fang Lijun (illustrated) , later innovations by key figure Yang Shaobin, and the feminist perspective of younger generation artist Duan Jianyu.

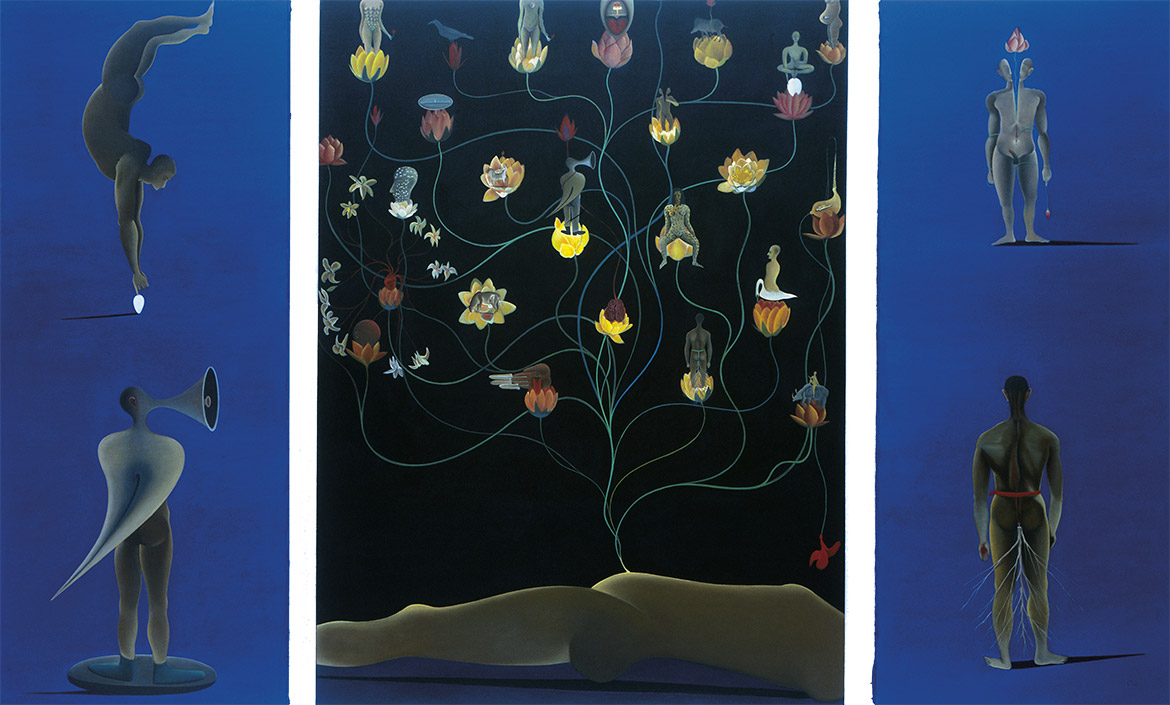

During a similar period, Indian artists of the Baroda School, who were inspired by the likes of Khakar and Mohamedi, rejected both the aesthetic purity of abstraction and the universalism of an earlier generation of Indian artists, and instead advanced a ‘figurative–narrative style’. Working with expansive pictorial planes, they incorporated a range of representational techniques while remaining firmly rooted in an immediate social reality. Several generations of artists, including NS Harsha, Nalini Malani, Pushpamala N (illustrated), Surendran Nair (illustrated) and Ravinder Reddy — all presented in ‘Reality and Invention’ — radically expanded the purview of postwar modernism to include popular idiom, rich art-historical references, and indigenous and vernacular styles. For their mentor, Gulammohammed Sheikh, this was a way of articulating experience of complexity amid social change, of ‘living simultaneously in several cultures and times’, a coexistence of past and present, ‘each illuminating and sustaining the other’3 — a fitting descriptor for the complicated reality confronted and engaged in by artists across this exhibition.

Reuben Keehan is Curator, Contemporary Asian Art, QAGOMA

Endnotes

1 Caroline Turner, ‘Internationalism and regionalism: Paradoxes of identity’ in Turner (ed.), Tradition and Change: Contemporary Art of Asia and the Pacific, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 1993, p.6.

2 Masahiro Ushiroshoji, ‘Realism as an attitude: Asian art in the nineties’, in 4th Asian Art Show Fukuoka: Realism as an Attitude [exhibition catalogue], Fukuoka Art Museum, Fukuoka, 1994, pp.33–8.

3 Gulammohammed Sheikh, ‘Among several cultures and times’, artist statement from Place for People [exhibition catalogue], Bombay and New Delhi, 1981, quoted in Chaitanya Sambrani, Edge of Desire: Recent Art in India [exhibition catalogue], Asia Society, New York, and Art Gallery of Western Australia, Perth, 2005, p.146.

‘Reality and Invention’ / Marica Sourris and James C. Sourris AM Galleries (3.3 and 3.4), Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) / 8 May to 19 September 2021.

Know Brisbane through the QAGOMA Collection / Delve into our Queensland Stories / Read more about Australian Art / Subscribe to QAGOMA YouTube to go behind-the-scenes

Featured image detail: Dede Eri Supria Labyrinth (from ‘Labyrinth’ series) 1987–88

#QAGOMA 2021-1