John Russell, like his contemporaries Claude Monet and Henri Matisse, were particularly captivated and inspired by the small island of Belle-Île, with its vivid turquoise waters, steep cliffs and craggy rock formations. Roger Benjamin visited France’s wild Atlantic coast to explore the island’s resonance as a motif in French painting.

In June 2018, before the height of the European summer, lecturing duties found me in La Rochelle, a venerable seaport on the Atlantic coast below Brittany. A curator friend invited me to stay on the remote island of Houat, off the narrow Quiberon peninsula that juts out into a shallow bay dotted with islands. Only upon peering closely at the map did I realise that Belle-Île was the island neighbouring Houat.

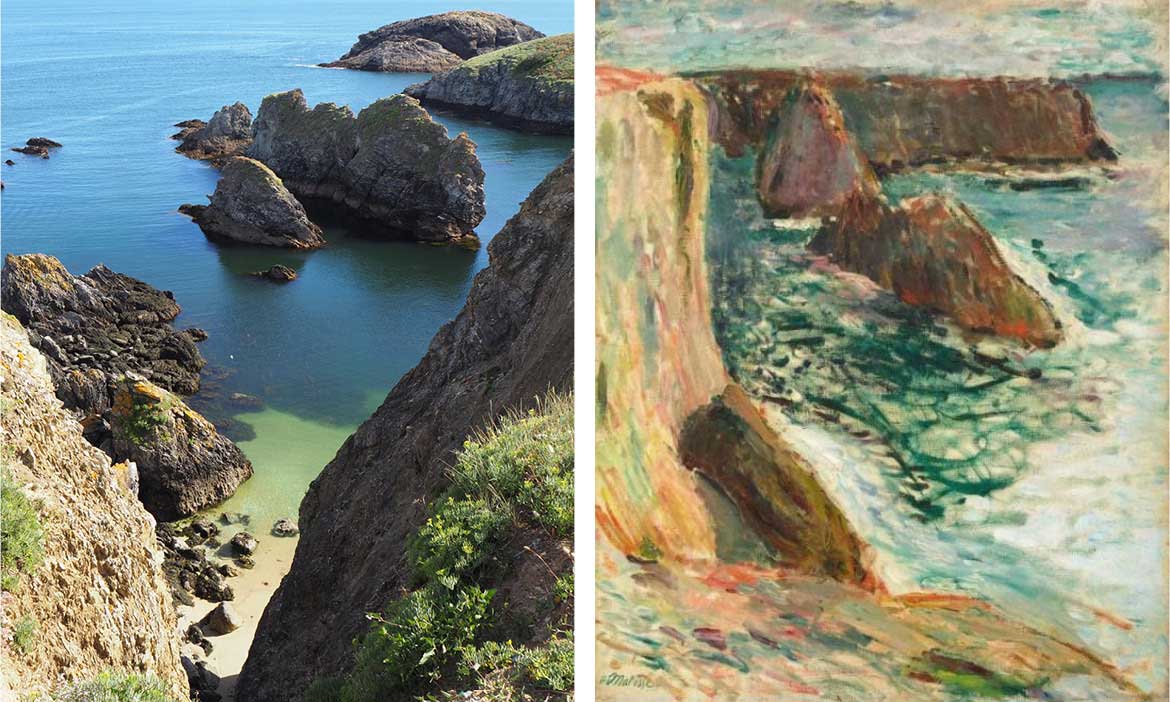

Belle-Île — a place of fable in the history of modern art. I had wanted to see it since my mid-twenties, spent researching the early career of Henri Matisse. The trainee painter had stayed on the island in the successive summers of 1896 and 1897, travelling with a now-obscure peer called Émile Wéry. Matisse also received lessons in colour on Belle-Île from John Peter Russell, an Australian painter and friend of artists. John Russell is chiefly remembered today thanks to research by Ann Galbally, my fine arts teacher at the University of Melbourne, who studied Russell for her doctorate and published the first book on him in 1977.1 QAGOMA holds fifteen works by Russell in its Collection, including several that date from the period he spent in France.

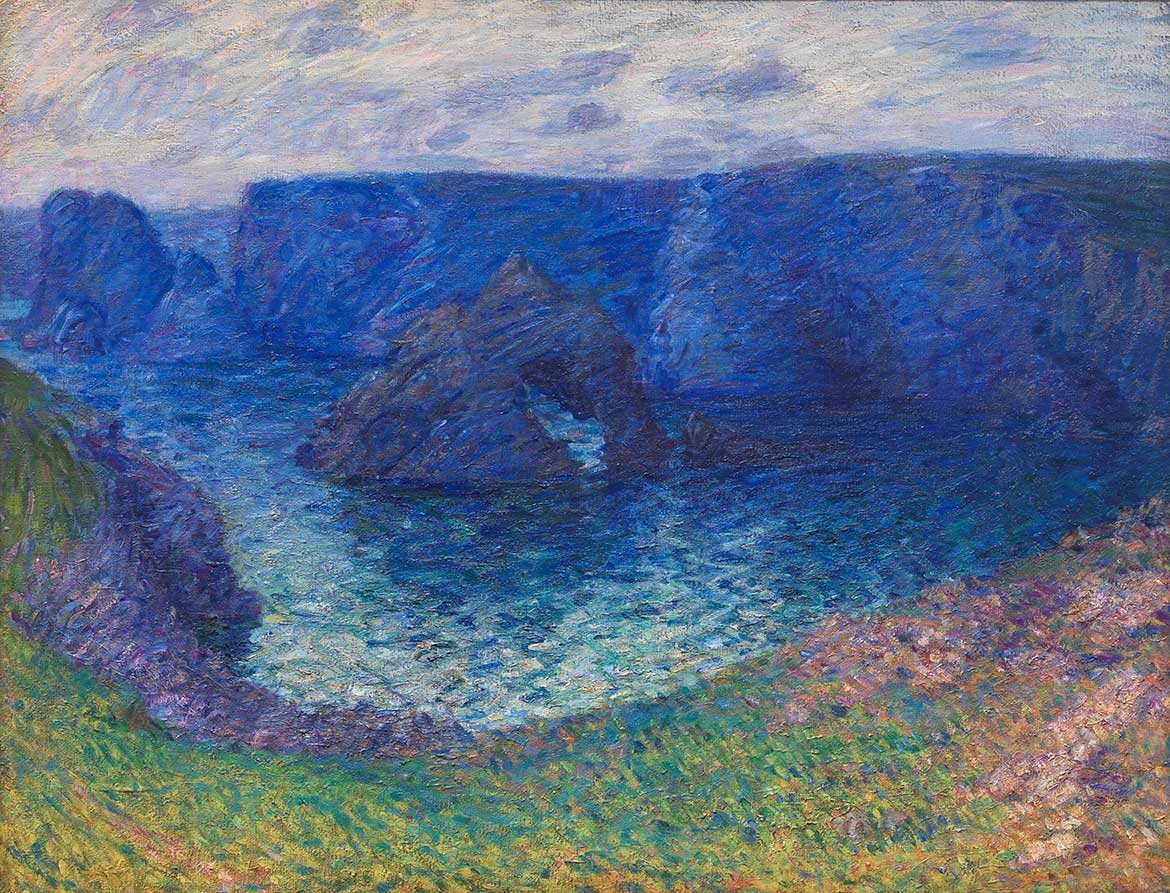

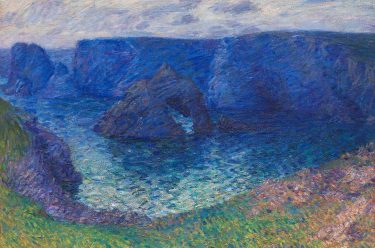

John Russell ‘Calm sea at Morestil Point’ 1901

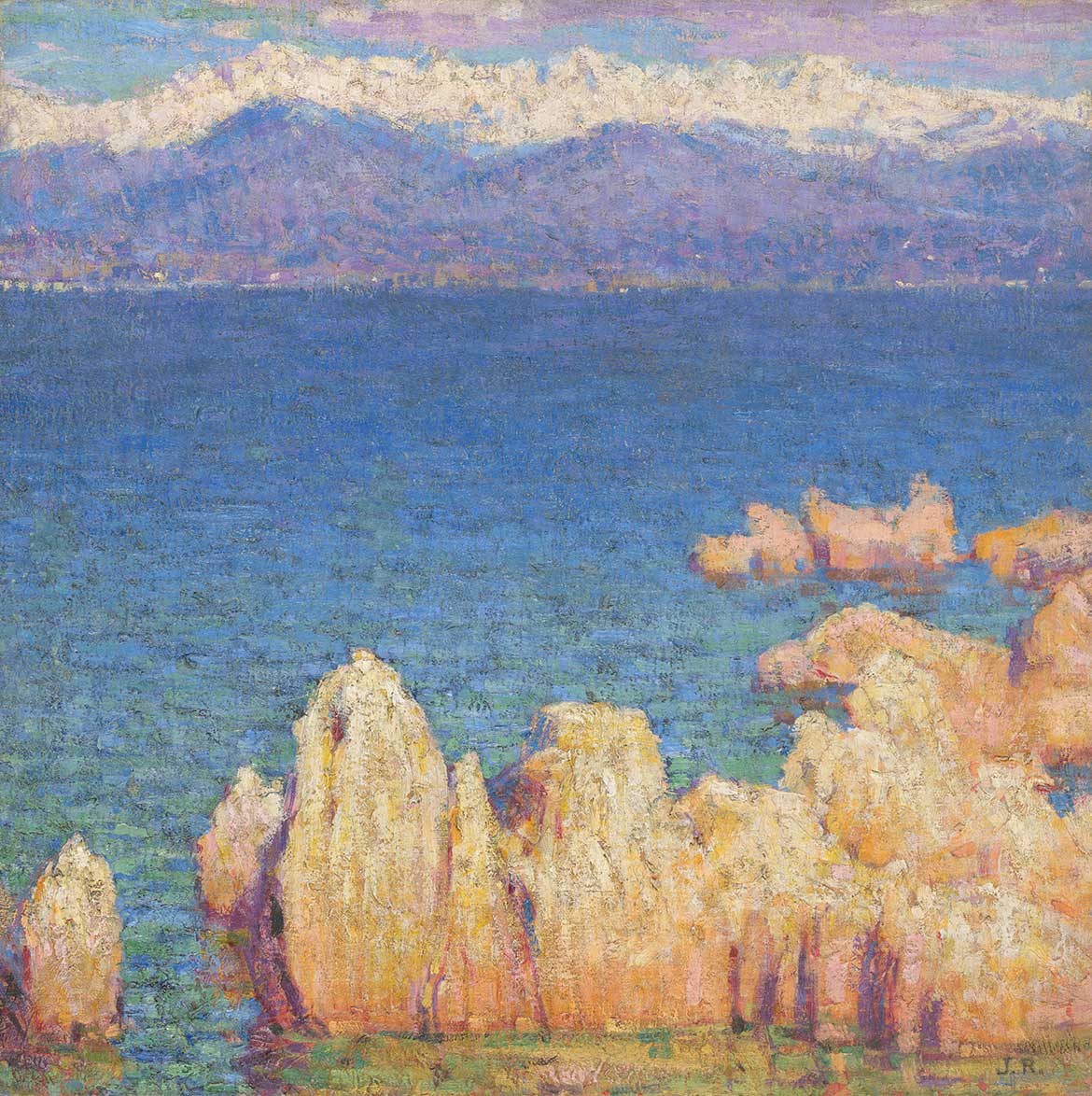

John Russell ‘Toul Rock (Guibel Rock’ 1904-05

Russell, Wéry and Matisse all painted Belle-Île in the wake of Claude Monet, who helped popularise the site as a destination for summer tourism in a series of great canvases of the Côte sauvage (‘wild coast’) in the summer of 1886. Monet’s Port Goulphar, Belle-Île 1887, acquired by the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) in 1949, has particularly resonated with Sydneysiders, who have always appreciated the appeal of great waves hammering a good sea-cliff. Thanks to this work by Monet we had heard of Belle-Île — but who ever travelled there? Maybe Dr Galbally, who located the Château de l’Anglais, the large country house built by Russell for his young family just metres inland from the same Port-Goulphar, and Matisse’s biographer Hilary Spurling.2

During my visit to France, the boat trip out to Belle-Île was a routine affair, conducted on a large diesel car ferry. Unlike the Island of Houat, on which private cars are forbidden, Belle-Île accepts tourists’ cars, ferried across at great expense while their holiday-making owners take in the view from the upper deck. The island has a long naval history, enshrined in the massive fortress — designed by Vauban, Louis XIV’s engineer — that overshadows the festive little port of Le Palais. Local histories emphasise the 1759 Battle of the Cardinals in Quiberon Bay, which saw a British fleet of forty ships defeat a French fleet intent on invading England.

The island well deserves its epithet of ‘the Beautiful’; in midsummer it is all green hedgerows, narrow winding roads lined by thick grass, fields of ripening wheat and rows of poplars. Villages of single-story stone houses, be they vintage or modern, punctuate the 17-kilometre length of the island. At its mid-point, just inland from Port Goulphar, is an enormous nineteenth-century lighthouse visible far out to sea.

Tourism and agriculture are Belle-Île’s two main industries, fishing having fallen away. Wealthy Parisian families might own a maison secondaire on the island. Many of the larger buildings in Le Palais contain hotels, and the easy hire of lightweight transport — bicycles and mopeds through to very small cars (mine was a Renault ‘Twingo’) — service the environmental and beach tourism of 2018.

What struck me in Le Palais was the lack of publicity about Belle-Île as a motif in French art. I would have though a little historic museum was obligatory, at the very least. Reproductions of Monets were not in every second cafe, as I expected. One morning in Le Palais I found a bookshop where, tucked in among the picture-postcards and guidebooks, was a well-researched hardcover, Belle-Île en Art, by local historian Henri Belbéoch.3 From it I learned that, although various artists painted there prior to Monet, in his wake literally dozens of artists — most of them impressionists of more or less orthodoxy — made the train trip to remote Quiberon and thence to Belle-Île. Their numbers included impressionists such as Armand Guillaumin, Henry Moret and Maxime Maufra, Fauves such as Jean Puy and Georges d’Espagnat, through to surrealist painter André Masson and the abstract artists Jean-Paul Riopelle and André Marchand.

My mission was to personally experience the motifs that Matisse, Monet and Russell had painted on the wild Atlantic coast,4 just as I had recently researched the visit of Russell and Tom Roberts to Granada, Spain, in 1883.5 The landscape did not disappoint. The waters along the Côte sauvage, famous for their immense storms, were completely calm on this summer afternoon. Port-Goulphar (described in the catalogue as a ‘fjord’), ‘The Needles’ (a kind of celtic Twelve Apostles) and Port-Coton (named for the great scuds of foam whipped up by winter storms) succeed one another along a three-kilometre stretch of coast. Pulling up in my Twingo, it was easy to park and to walk along well-kept gravel paths just metres from rocky cliffs that fell thirty or forty metres to the water. Peering straight down from such giddy heights, I saw that the clear waters were tinted green — as Gustave Flaubert wrote in his matchless travelogue of 1847 — by seaweed laid over grey pebbles.6 There were no restraining bollards or fences; instead, prim little panels exhorted visitors to respect the native vegetation and to remove their litter.

All I could hear was the whistling of the breeze straight off the Atlantic, although near the site of Russell’s former mansion, a reception centre was hosting a high-end wedding party whose very vows, to my chagrin, were broadcast towards the fabled cliffs where rustic landscapists had once roamed free.

Back at my hotel outside Le Palais, the hotelier knew little of the visual arts and was surprised to hear that an Australian had been one of the most prolific painters of Belle-Île 120 years before. Visitors to the mainland provinces of Vendée and Morbihan are today more likely to be professional rugby players or trainee vintners than artists. The Sydney painters Euan Macleod and Luke Sciberras are fascinating exceptions.7

My last morning on Belle-Île saw me up with the lark, heading to the remote northern tip of the island and the port town of Sauzon, with its lighthouse and chugging fishing boats. A few miles beyond lie the rocky outcrops of Les Poulains (‘the Colts’), a dramatically picturesque zone of craggy schist monoliths breasting the waves like young horses. Although embraced by painters, the locale is best known today for the Château of Sarah Bernhardt, an unprepossessing blockhouse sheltering among grassy folds close to the sea. A century ago, the world-famous actress sought seclusion there in the twilight of her career. Today, the odd dog-walker or jogger aside, a few illustrated panels vaunt the project of restoring the dune vegetation and the shingle beach to its pristine, savage beauty.

My impression is that Monet said just about all there was to say on Belle-Île as a motif for painting. He brilliantly grasped that, on the Côte Sauvage, the plateau is almost flat before the cut-away of the crags, giving versatile horizon lines that are as solid and natural as those provided by the sea. Not content to merely copy Monet, Matisse had trouble with the cliffs and fjords in the half-dozen views of them that survive. He often seemed to prefer the modest goal of depicting the farmhouses emerging from the muddy plains of Kervilahouen, the village where both Monet and Matisse lodged. He also dealt with the port scene at Le Palais, bringing the hulls of small steam packets and fishing boats into proximity with the vast — and in his works almost unintelligible — geometric forms of Vauban’s spectacular fortress.

John Russell ‘Rocks at Belle-Ile’ c.1900

Russell is said to have destroyed Belle-Île canvases in despair following the death of his muse (and the mother of his seven children), Marianna Mattiocco in 1908. Of his surviving works, Russell outdid his friend Monet in conveying the sublime energy of the tempests that battered the Belle-Île coast every winter; Russell had, after all, lived there for two decades. The best time to visit Belle-Île for ‘les tempêtes’, my hotelier told me, is in the depths of January, when a hardy new breed of winter tourist appears to witness extreme weather. Would that I might one day join their number, and complete my pilgrimage to the Côte sauvage, begun as an accidental tourist on a cheery June day.

Roger Benjamin is Professor of Art History at the University of Sydney

Endnotes

1 Ann Galbally, The Art of John Peter Russell, Sun Books, Melbourne, 1977.

2 Wayne Tunnicliffe (ed.), John Russell: Australia’s French Impressionist, Sydney, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2018. The exhibition runs from 21 July – 11 November 2018.

3 Henri Belbéoch and Florence Clifford, Belle-Île en Art [self-published], Plonévez-Porzay, France, 1991.

4 See Ursula Prunster and Ann Galbally, Belle-Île: Monet, Russell & Matisse in Brittany, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2001.

5 See Roger Benjamin, Emilio Escoriza and Emma Kindred, ‘Tom Roberts and Friends at the Alhambra’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, vol.15, no.1, 2015, pp.52–74.

6 Gustave Flaubert, ‘Belle-Isle’, in Par les champs et par les grèves (Voyage en Bretagne), Paris, 1881.

7 The exhibition ‘Belle Île: Luke Sciberras & Euan Macleod’ ran from 13 July to 2 September 2018 at the Manly Art Gallery and Museum, Sydney.

Delve deeper into the Collection

John Russell ‘Almond trees and ruins, Sicily’ 1887

Amandiers et ruines, Sicile (Almond trees and ruins, Sicily) is an early work painted during John Russell’s visit to Sicily in 1887. After meeting Claude Monet at Belle-Île in the summer of 1886, Russell returned to classes in Paris. Feeling that he needed to make substantial changes to his work to encompass all he had learnt, he set out to explore the southern coastlines of Italy. Settling for a time in the Sicilian town of Taormina, in the shadow of Mount Etna, Russell travelled to the other side of the island to view the Hellenic ruins overlooking the Mediterranean at Agrigento. This spectacular site, around 1 000 metres above sea level, houses several Greek temples. Russell chose to paint the picturesque temple of Castor and Pollux, comprising just four columns and a portion of architrave scavenged from other temple sites, a reconstruction made in 1836. Russell’s painting inspired Van Gogh to paint similar scenes in the south of France.

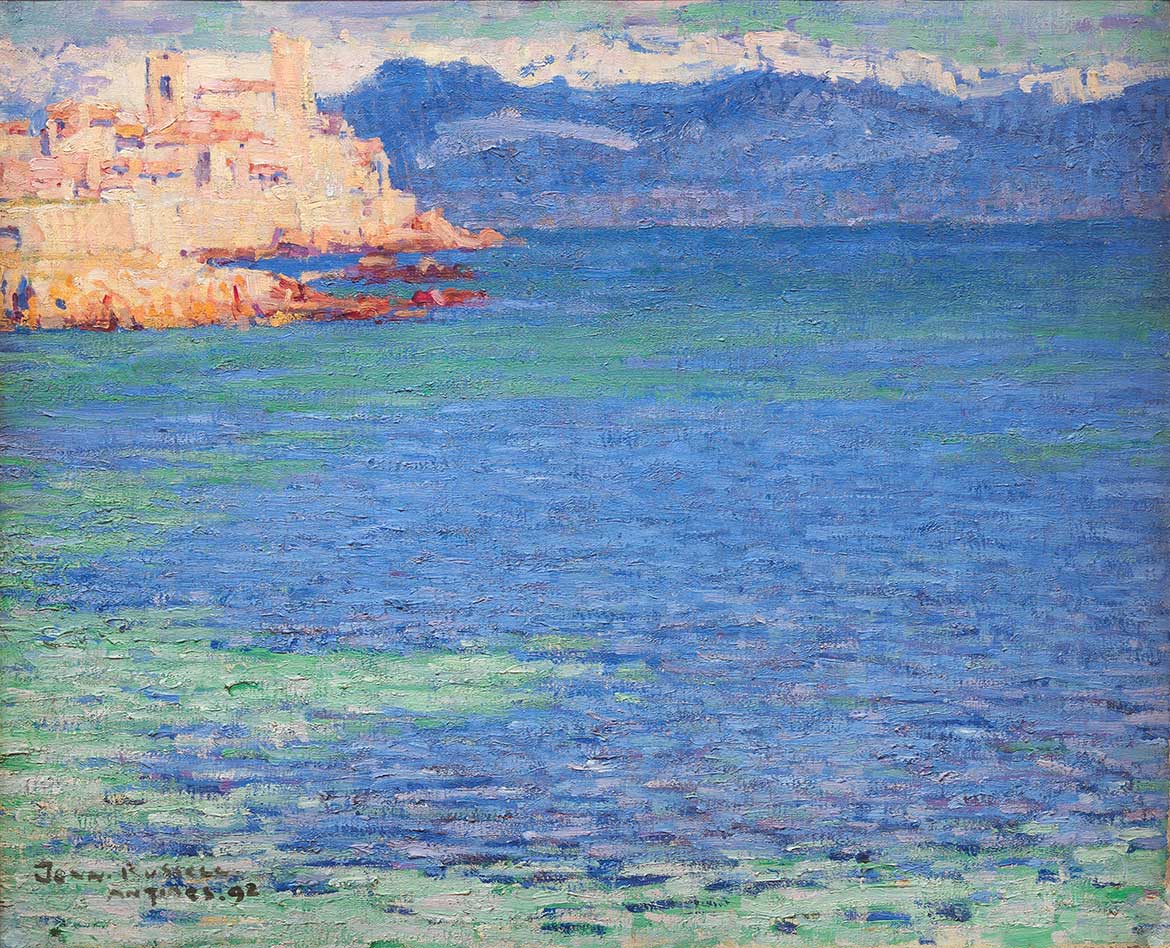

John Russell ‘The route du Littoral on the West side of Cap d’Antibes, looking towards Nice, the Baie des Anges and the Alps’ c.1890s

John Russell ‘View from Hotel Jouve, plage de la Sallis, looking towards the medieval walls and the Grimaldi Castle, Antibes 1892

John Russell’s seascapes, portraying the alternately stormy and calm aspects of the Côte d’Azur, are characteristically Impressionist in technique, high-keyed and preoccupied with light, colour and a sketch-like facture. The heavily textured paintings are worked in pure colour, the pure strokes of complementary colours, placed one beside the other, resonate and convey an effect of immediacy, the result is an impression of nature at a particular moment.

Featured image: John Russell’s Rochers de Belle-Ile (Rocks at Belle-Ile) c.1900 / Chosen for the cover of the AGNSW retrospective, ‘John Russell: Australia’s French Impressionist’ 2018

#QAGOMA

thank you for this information and superb paintings ..we are very fortunate to have such works in our collection

Thank you for this delightful post, I have long been an admirer of John Russell’s works and it is great to see that an expert can validate my thoughts and opinion that his sea paintings of Belle Isle en Mer outdo Monet’s!

Thank you. A French friend has invited us to stay at her holiday house on Belle-Ile and I was intrigued to learn that John Russell had stayed and painted there. We have in common a love of wild seas and big waves so it was fascinating to see Russell’s impressions. I am now motivated to visit the Queensland Art Gallery to see the Russell paintings and of course to visit Belle-Ile.