Queensland-born artist Gordon Bennett (1955–2014) was deeply engaged with questions of identity, perception and the construction of history, and made a profound and ongoing contribution to contemporary art in Australia and internationally.

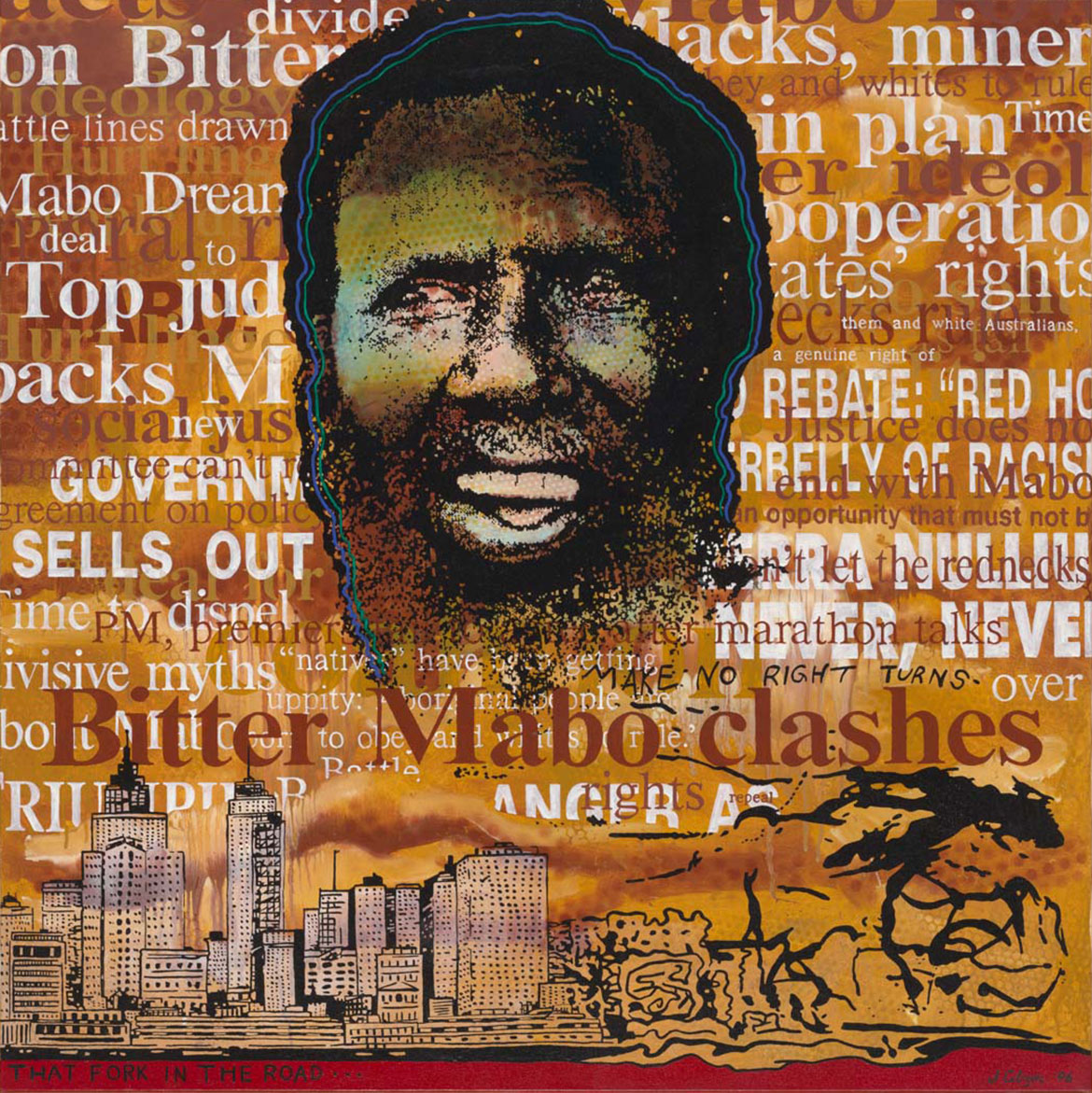

To me, the image of Eddie Mabo stood like the eye of a storm, calmly asserting his rights while all around him the storm, a war of words and rhetoric, raged. Gordon Bennett

A riot is the language of the unheard. Martin Luther King1

Bennett developed a unique form of appropriation and is known for his layering and repetition of elements from paintings by artists such as Kazimir Malevich, Piet Mondrian, Philip Guston, Margaret Preston and Jackson Pollock, as well as his sustained dialogue with the work of Haitian–American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat. These exchanges and excavations enabled Bennett to address the legacies of Western art and its relationship to colonial perspectives on non-Western cultures. One previously unexamined intersection is with the work of American artist David Hammons.

John Citizen ‘Eddie Mabo’ 1995

On 2 June 2020, ‘Blackout Tuesday’, there was an international expression of solidarity with the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protesters in the United States, following the murder of George Floyd. In Australia, Blackout Tuesday preceded Mabo Day on 3 June — a commemoration of Indigenous activist Eddie Koiki Mabo (1936–92) and his decade-long fight for the recognition of traditional ownership of the land.2

David Hammons ‘African-American Flag’ 1990

The alignment of dates seemed fitting, drawing attention to the way in which racial prejudice and violence in the United States mirrors Australia’s ongoing issues with Indigenous rights, including Aboriginal deaths in custody.3 To mark Mabo Day 2020, Gordon Bennett’s painting Eddie Mabo (After Mike Kelley’s ‘Booth’s Puddle’ 1985, From Plato’s Cave, Rothko’s Chapel, Lincoln’s Profile) No.3 1996 was projected at vast scale against the National Carillon on Lake Burley Griffin in Canberra.4 Coincidentally also the day Bennett passed away in 2014, it was a fitting tribute to two men — one an activist, the other one of Australia’s most highly regarded contemporary artists — who fought for humanity and justice in different ways.

In the United States, another artwork became associated with the BLM protests: David Hammons’s African-American flag 1990 was posted on social media and replicas were carried by demonstrators. First created for an exhibition in 1990, the flag combines the stars and stripes of the US flag with the red, green and black of the Pan-African flag.5 A hybrid creation, the ironic juxtaposition of elements draws attention to an uneasy coexistence, while also acting as a symbol of strength, resistance and unity to people of African- American descent.

Kazimir Malevich ‘Hieratic Suprematist Cross’ 1920-21

Gordon Bennett encountered David Hammons’s work as early as 1990, and mentioned him as an influence in his private notebooks. In June 1990, Bennett travelled to Amsterdam for the centenary exhibitions associated with Vincent van Gogh’s death.6 Then, on 9 June, he visited the exhibition ‘Black USA’ at Amsterdam’s Museum Overholland, writing in his notebook that it was ‘practically deserted, no line-ups, no crowds’.7 Identified as a watershed moment in art history, the exhibition included work by seven artists: David Hammons, Jules Allen, Benny Andrews, Romare Bearden, Robert Colescott, Martin Puryear and Bill Traylor. Hammons’s African-American flag, created specifically for the exhibition, flew outside the museum’s front door. In the days prior, Bennett had been viewing the abstract paintings of Russian artist Kazimir Malevich at the Stedelijk Museum. Malevich’s most renowned work is Black Square 1915, often regarded as the pinnacle of ‘pure abstraction’. In ‘Black USA’, however, black shed its formalist association with transcendence and purity and instead related to the skin, bodies and experiences of Black Americans. In addition, the works disrupted formalist readings of abstraction by alluding to blood, gunshots and lynchings, and through the use of materials connected to incarceration and slavery, such as wire and nooses.

Gordon Bennett ‘Notebook sketch after David Hammons’ 1993

Gordon Bennett ‘Notebook sketch 2 July’ 1993

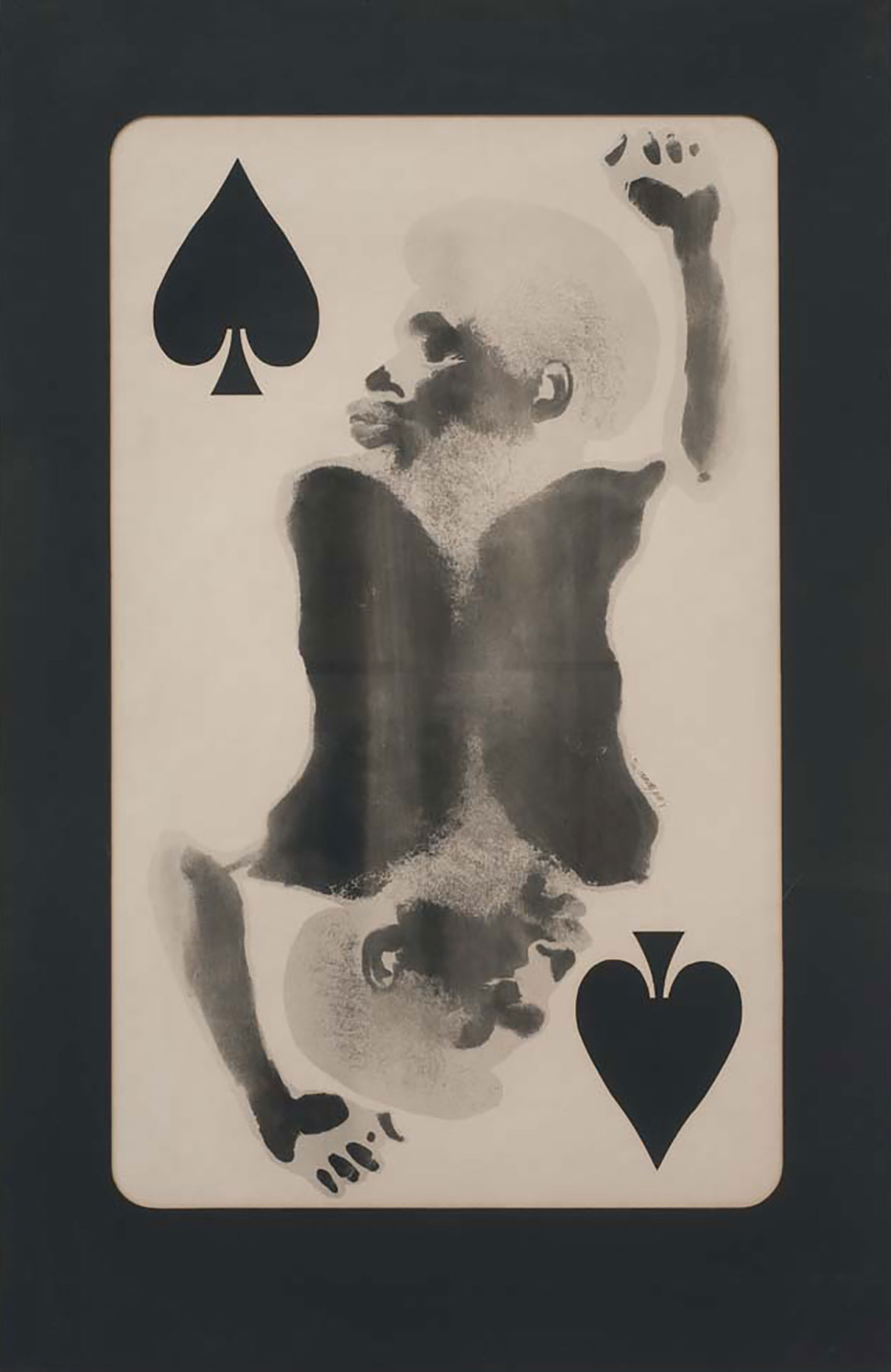

David Hammons ‘Spade (Power for the spade)’ 1969

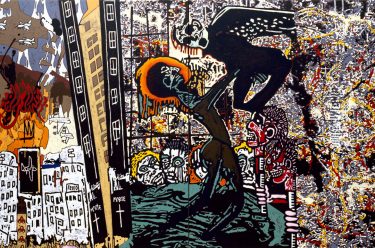

Both Hammons and Bennett began practising as artists at times when issues of sovereignty and civil rights were coming to the fore in their respective countries. Hammons’s ‘body prints’, like America the beautiful 1968 or Spade (Power for the spade) 1969, were made after Martin Luther King’s assassination in 1968, which sparked violent uprisings and race riots across the country. In Australia, Bennett graduated from college in 1988 — the bicentenary year marking Captain James Cook’s ‘discovery’ and ‘possession’ of Australia7 — and witnessed historic moments such as the Mabo decision of 1992, which led to the Native Title Act 1993. Paintings such as his Possession Island 1991, Outsider 1988 and Myth of the Western Man (White man’s burden) 1992 directly refer to these events.

Gordon Bennett ‘Possession Island’ 1991

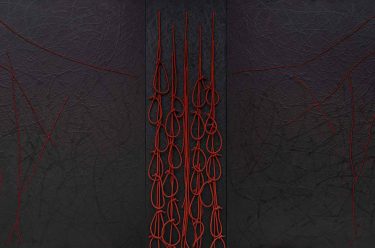

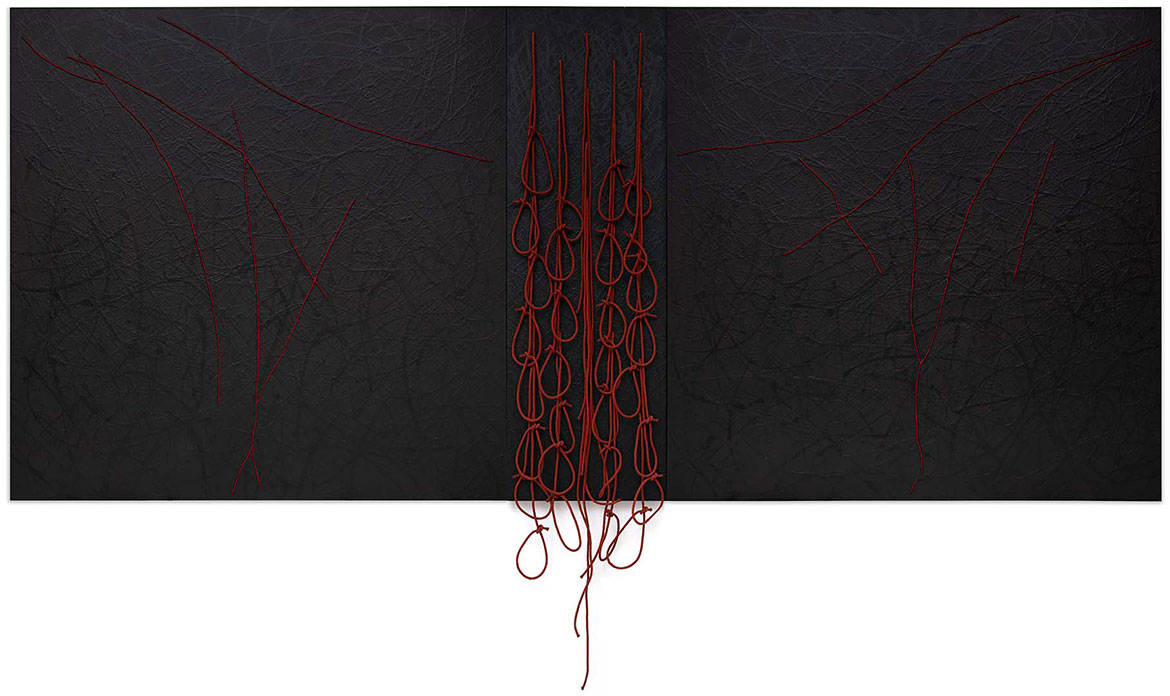

Bennett made two sketches for works ‘after David Hammons’ in 1993. Both related to Hammons’s series of ‘spade’ works, which played on the literal and derogatory meanings of the word. For Hammons, the spade symbol (like that seen on playing cards) encapsulated and signified ‘blackness’ and the experience of being Black in America. One of Bennett’s sketches directly alluded to Hammons’s Spade with chains 1973, a wall-based work made from an actual tool looped with chains, suggesting a makeshift African mask, the destruction of culture and a history of slavery. Bennett’s sketch showed a rectangular spade with chains on either side, threaded with blank cards that he planned to write or paint on. This spade would later morph into a stockman’s whip, more accurately representing Australian colonial history, hung with the same cards and the letters a/b/c/d (Bennett’s cipher for the derogatory words ‘abo, boong, coon, darkie’). The stockman’s whip became part of his ‘Welt’ painting Self‑portrait interior/exterior 1992 and was also a component of Self-portrait (Suit) c.1995. These black, scarified, ‘poxed’ and cut works also included the triptych Bloodlines 1993, with its central panel of red oxide‑stained nooses alluding to Aboriginal deaths in custody.

Gordon Bennett ‘Self-portrait (Suit)’ c.1995

Gordon Bennett ‘Bloodlines’ 1993

paint and rope on canvas on wood / Triptych: 182 x 420cm (overall) / Purchased 2019 with funds from the Neilson Foundation through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Estate of Gordon Bennett

Bennett’s ‘Altered body print’ series of 1993–94 also points to Hammons’s body prints, in keeping with his practice of visual quotation and re-presentation. In the late 1960s, Hammons used margarine to grease his body, hair and clothing, before rolling on a sheet of paper, leaving an imprint that he then sprinkled with black pigment. The resulting images — seen in Spade (Power for the spade), for example — appear violently compressed and downtrodden, in keeping with prevalent racial and class stereotypes. (One of Hammons’s most shocking images, Injustice Case 1970, alludes to the silencing of Black Panther Bobby Seale during his trial.) For his ‘Altered body print’ series, Bennett painted his skin black, and pressed his chest, hands, pelvis, thighs and feet onto canvas or paper while supporting his weight on his arms. The impressions he left were distorted and splayed, suggesting a kind of dismemberment. While Hammons used grease for its association with the everyday, Bennett’s works alluded to Aboriginal body painting as well as Yves Klein’s Anthropometries series of 1960, creating works that fused European, colonial and Indigenous references.

Gordon Bennett’s ‘Body prints’ performance in the Petrie studio 1994

Gordon Bennett ‘Altered body print (Purity of hybrids)’ 1994

Like Hammons’s Spade (Power for the spade), Bennett’s diptych Altered body print (Purity of hybrids) 1994 raises questions of race, skin and identity. On the left panel, a headless figure with disjointed limbs appears against an ochre background, accompanied by Kazimir Malevich’s crucifix symbols in red and black — a repeating motif in Bennett’s practice, signifying both the association of abstraction with purity and the Christianity imposed on a colonised and subjugated people. The outline of a falling baby on the right is perhaps a reference to the Stolen Generation, as well as the recent birth of his daughter and his fears that she would be subject to the same experience of racism he had encountered.

Bennett and Hammons shared a similar visual language and a humanist desire to participate in the creation of a better world. Hammons expressed his sense of a ‘moral obligation as a black artist to try to graphically document what I feel socially’, while Bennett acknowledged his foolishness in wanting to create ‘the one painting that will change the world, before which even the most narrowminded and rabid racists will fall to their knees in profound awareness and spiritual openness’.8 Adopting objects, symbols and materials as signifiers of Black and Indigenous bodies, cultural histories and identities, each played on the ‘slipperiness and subterfuge’ of language, creating provocative works that have been highly influential on following generations of artists.9

David Hammons and Gordon Bennett grew increasingly reticent as their careers progressed, refusing to be interviewed or to attend openings. Both artists felt trapped by the association of their work with ‘blackness’.10 To see their artworks reappear in the context of Black Lives Matter highlights both the ongoing pertinence of their practices and how very far we have yet to go.

Abigail Bernal is former Assistant Curator, International Art, and co-curator of ‘Unfinished Business: The Art of Gordon Bennett’.

Endnotes

1 See Lily Rothman, ‘What Martin Luther King Jr really thought about riots’, Time, 28 April 2015, https://time.com/3838515/baltimore-riotslanguage- unheard-quote/, viewed 3 July 2020.

2 Mabo day marks the anniversary of the historic Mabo decision of 1992, when it was decided that the Mer people (from Murray Island) were the traditional owners of the land. This was a significant ruling which refuted the idea of terra nullius and led to the Native Title Act 1993.

3 This confluence was also acknowledged in the social media hashtags #blacklivesmatter and #indigenouslivesmatter associated with demonstrations in Australia.

4 The National Carillon was a gift from the British Government to the people of Australia to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the national capital. Queen Elizabeth II accepted the National Carillon on behalf of Australians on 26 April 1970.

5 Marcus Garvey’s Pan-African Flag with three horizontal stripes in black, red and green was first adopted by the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League in 1920. The colours are symbolic, with red for blood, black for skin, and green for the fertile land they forcibly left behind. David Hammons’s flag was initially created as an edition of five, and there are a number of subsequent variations on the theme in public collections in the United States and Europe.

6 The Museum Overholland was in a prominent position, surrounded by the Rijksmuseum, the Van Gogh Museum, the Stedelijk Museum, and also the US Consulate General, making Hammons’s flag even more politically apt and the lack of crowds during the Van Gogh centenary more notable.

7 As with other countries ‘discovered’ and colonised by European explorers, the celebration of this moment excluded First Nations people, denying their long habitation of the land and the history of violence that followed.

8 Gordon Bennett quoted in Bernhard Luthi (with Gary Lee), Aratjara: Art of the First Australians: Traditional and Contemporary Works by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Artists [exhibition catalogue], DuMont, Koln, 1993, p.91.

9 Gabriel Cox, ‘David Hammons’, Art Review, May 2016, https://artreview.com/may-2016-feature-david-hammons/, viewed 3 July 2020.

10 Hammons jokingly remarked that he would love to make works with light like James Turrell, but he was not ‘free’. His full comment was: ‘[Turrell’s] got a completely different vision. Different than mine, but it’s beautiful to see people who have a vision that has nothing to do with presentation in a gallery. I wish I could make art like that […] I would love to do that because that also could be very black. You know, as a black artist, dealing just with light. They would say, “How in the hell could he deal with that, coming from where he did?” I want to get to that, I’m trying to get to that, but I’m not free enough yet. I still feel I have to get my message out’. See ‘David Hammons turned off the lights in an empty gallery. What happened next was a masterpiece’, Artspace, 9 March 2016, https://www.artspace.com/magazine/art_101/book_report/davidhammons-phaidon-dca-excerpt-53590, viewed 20 August 2020.

Acknowledgment of Country

The Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land upon which the Gallery stands in Brisbane. We pay respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander elders past and present and, in the spirit of reconciliation, acknowledge the immense creative contribution Indigenous people make to the art and culture of this country. It is customary in many Indigenous communities not to mention the name of the deceased. All such mentions and photographs on the QAGOMA Blog are with permission, however, care and discretion should be exercised.

Featured image detail: Gordon Bennett Possession Island 1991

#QAGOMA