Exploring art is not just a visual experience, the act of seeing can trigger a whole range of responses, our sensory awareness is awakened by visual cues by engaging our memories of smell, sound, touch and feel. From the slipperiness of soap to the flickering wick of an oil lamp, visceral connections increase the depth of visual enjoyment.

LIST OF WORKS: Discover all the artworks

DELVE DEEPER: More about the artists and exhibition

THE STUDIO: Artworks come to life

WATCH: The Met Curators highlight their favourite works

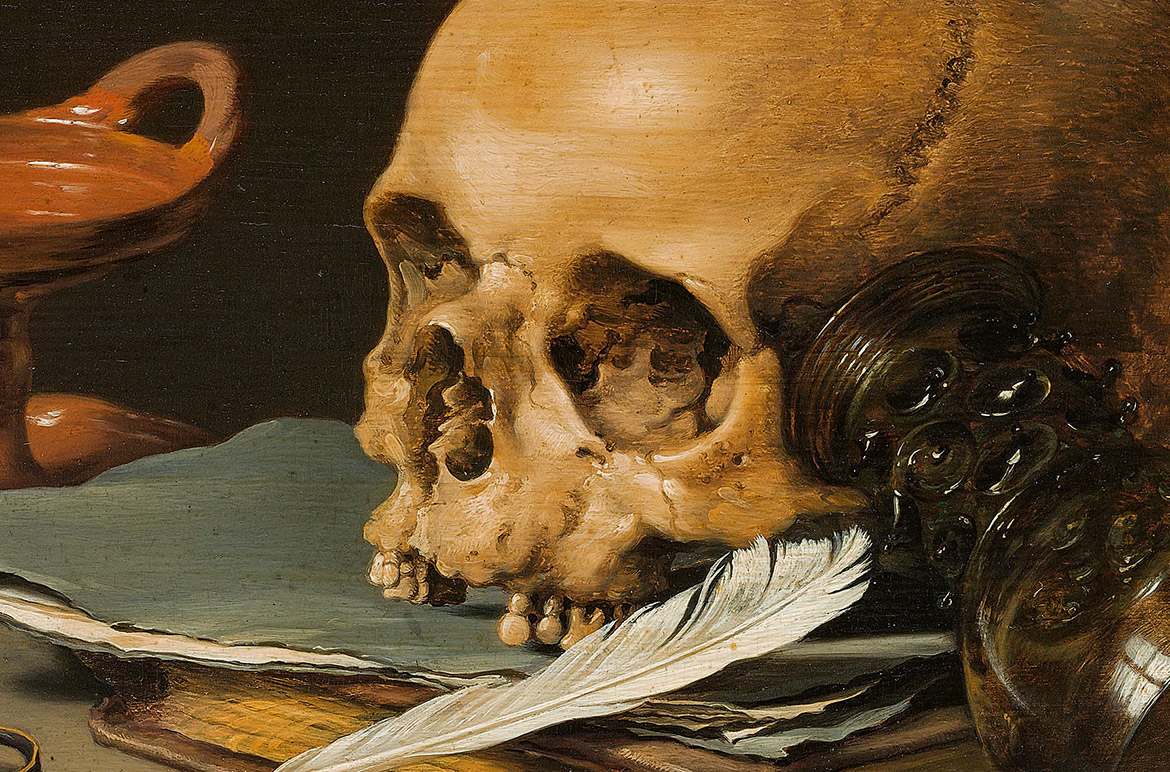

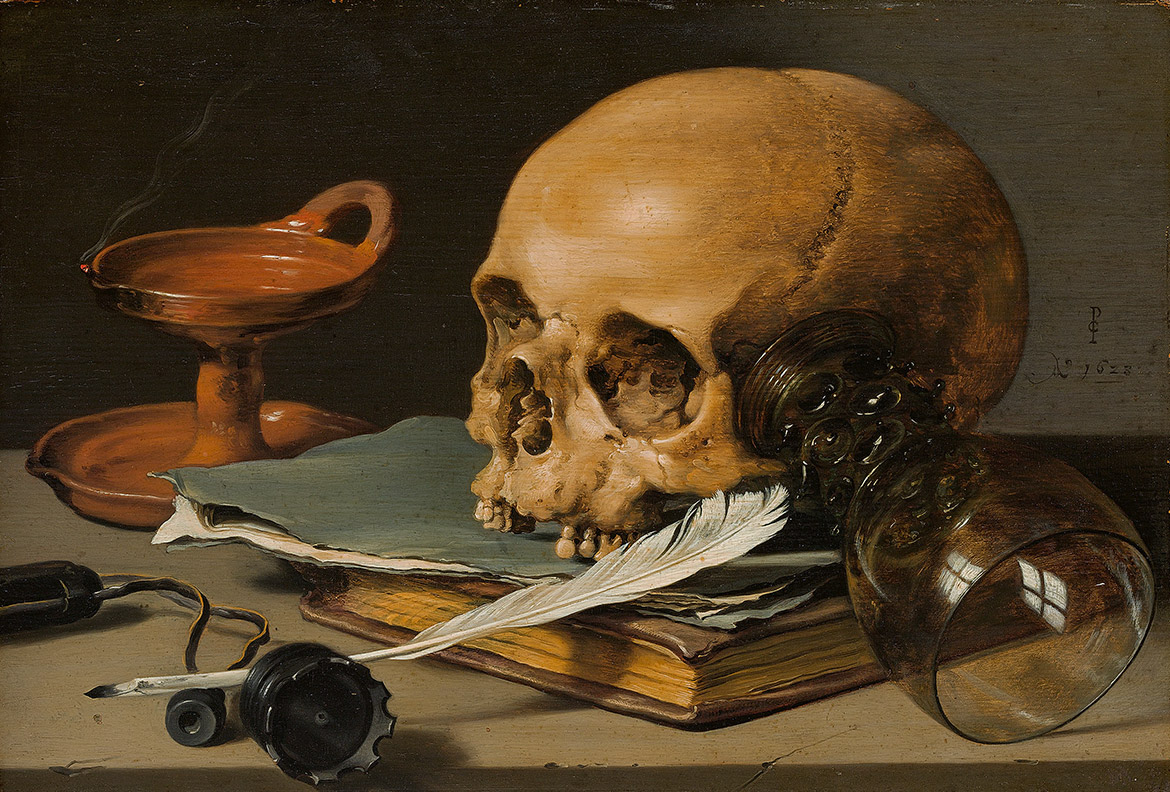

Pieter Claesz ‘Still Life with a Skull and a Writing Quill’ 1628

In Still Life with a Skull and a Writing Quill 1628 by Pieter Claesz, close observation and realistic detail operate in tension with explicit symbolism. Working with a limited palette of grays and browns, the toppled glass, gap-toothed skull, and flickering wick of an oil lamp all serve as stark symbols of life’s brevity.

In the seventeenth century, still-life painting flourished in Holland and Claesz was one of the finest still-life painters of the Dutch Golden Age. At a time of great mercantile wealth and frequent military conflict, vanitas paintings were meant to suggest that life is short and we ought to savour every moment. The Dutch Republic was becoming an important trading centre as commodities from around the world passed through its ports and into homes. Artists used commonplace objects to formulate what were often metaphysical symbols for intellectual and artistic accomplishments, or meditations on human purpose, faith and life after death. The futility and transience of life was explored by the use of objects symbolising worldly accomplishments — such as art and learning, wealth and earthly delights — as well as stark reminders of human mortality.

Dominating the composition the human skull resting on a worn stationery folder and leather-bound book, and writing quill, inkwell and toggled leather pen case lay claim to learned achievements. Propped against the skull is an overturned drinking glass, polished to sparkle, it reveals the subtle reflections of a window and poignantly alludes to past pleasures. A recently extinguished earthenware oil lamp, its wick still aglow, emits a thin plume of smoke to demonstrate that life is quickly passing us by.

A vanitas composition is not just a reminder of death and decay but also an encouragement to embrace more fully the pleasures of life.

Jean Siméon Chardin ‘Soap Bubbles’ c.1733–34

In Soap Bubbles c.1733–34 a delightful and playful scene is enacted. Framed within a window, a boy with curled hair is absorbed in blowing a bubble, while his younger companion peers over the sill to catch a glimpse. The older boy endeavours to blow just enough air into his bubble to expand it to the maximum extent, while the younger boy looks on, wide-eyed and enthralled by its fugitive mix of elasticity, surface tension, chemistry and light.

Despite the simplicity of its title and subject, the painting is emblematic of the era’s emerging scientific approach to understanding the world and its origins. These are the children of the Enlightenment, caught in a moment of play and curiosity about the world.

Jean Siméon Chardin drew inspiration from the seventeenth century Dutch genre tradition for both the format and the subject. While it is not certain that the artist intended the picture to carry a message, soap bubbles were then understood to allude to the transience of life. Soap Bubbles can be seen as a vanitas image, Chardin using the delicacy of a soap bubble to allude to life’s fragility. The artist was a pioneer in the rejection of mythological and historical subject matter. Instead, Chardin sought to portray the ordinary in life, and a favourite topic was children playing.

This Australian-exclusive exhibition was at the Gallery of Modern Art from 12 June until 17 October 2021 and organised by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in collaboration with the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art and Art Exhibitions Australia.

Featured image detail: Pieter Claesz Still Life with a Skull and a Writing Quill 1628

#QAGOMA #TheMetGOMA