‘Unfinished Business: The Art of Gordon Bennett’ presents the work of an artist deeply engaged with questions of identity, perception and the construction of history. Simon Wright, a long-time friend of the artist, recalls the man in the studio in our two part series, beginning with his studio under the family home in Petrie.

DELVE DEEPER: Read about GORDON BENNETT’S STUDIO AT SAMFORD VALLEY

RELATED: The art of GORDON BENNETT

The painting space Gordon Bennett worked in during the late 1980s, as he studied and then graduated from Queensland College of Art, Brisbane (QCA), was cramped and modest. He and his partner, Leanne, converted their garage and set it up as a purely functional area under the family home on Deckle Road, Petrie: on the outer edge of Brisbane, with virtually no natural light, rising damp, and barely enough space to cut and stretch his own canvases. He established highly pragmatic ways to keep things moving there, with every material, paint pot or tool methodically positioned and labelled. The maximum dimensions of major works made at this time, for example, equalled Gordon’s own height and the width of his outstretched arms or comprised two or three units at that scale rather than one vast surface. He often unpicked blank, primed and pre-stretched canvases from their stretchers and stapled them to ply boards erected as makeshift walls, increasing the available surface space on which to paint. Gordon soon came to dislike this method, however, due to the difficulty of re-stretching painted works later and because there was little room to get long views on works, or to document them.

RELATED: Read about AUSTRALIAN INDIGENOUS ART

SIGN UP NOW: Be the first to know. SUBSCRIBE TO QAGOMA BLOG for the latest announcements, acquisitions, and behind-the-scenes features.

Despite space limitations, Gordon was determined to keep as much of his process in-house as possible. Just as the content of his work resonated with his lived experience, he also spent much time and skill creating the conditions for his work to be realised and documented — from cutting and priming substrates to DIY lighting for photography. As a former fitter and turner and Telecom linesman, completing manual tasks other artists usually outsourced or making products usually bought off the shelf gave Gordon a quiet sense of fulfilment and helped to build his confidence as an artist. It also drove necessary changes to ensure the studio remained functional and safe: fumes from the oil paints and cleaning solvents he used at that time, for example, were an ongoing challenge in such closed quarters, and it was not long before these were replaced with water-based synthetic polymer paints. This switch from oils to acrylics was a key early developmental shift in Gordon’s studio practice and led him to discover a new high-quality product, known as Derivan Matisse Flow Formula acrylic, which would become a favourite staple. The shift was also an early indicator that Gordon could adapt any medium to arrive at the image he was seeking. It was the conceptual and suggestive power of a work — its attendant narrative and contexts — rather than the medium he used to get there, that really mattered.

Gordon’s days were scheduled around his life as a mature-age art student, and the QCA’s studio-like teaching spaces and open critique presented him with a disciplined way of working. Rooted in centuries of Western tradition, this way of making art was a useful context for his analyses of representation, Modernism and the canon he studied. Accordingly, although Gordon’s voracious reading, notetaking, research and sketching was peripatetic, any act of ‘making’ a painting had to happen in his own dedicated studio space. The converted undercroft at Deckle Road suited his independent temperament and natural inclination for isolation; for him to have a very private retreat, far from the madding crowd, was ideal. Here, he could be immersed in his thinking and interact with the outer world on his own terms. This was no ‘drop-in’ or social zone, like university, and he was never one to be camera-ready or eager to show off a new work, even to friends, fellow students or, later, dealers. His studio was especially off-limits to the neighbourhood as well as the news and art media. It was difficult for Gordon to deal with his remarkable early success on leaving art school and the sudden interest in ‘him’ instead of in his work, especially given an early decision to avoid interviews as much as possible. The subsequent announcement and documentation of his ongoing work Non-Performance 1992–2014 — a refusal to talk about his practice in public — gave him an added sense of privacy which, ironically, further aroused curiosity and interest in his art.

Only a few years after graduating, Gordon won Australia’s biggest contemporary art award, the Moët & Chandon Australian Art Fellowship, which had a profound impact on his studio practice. Between July 1991 and June 1992, as part of the prize, Gordon and Leanne resided at a rustic, two-storey Moët & Chandon property in Hautvillers, on the outskirts of Epernay, France. Larger living and working spaces were a welcome sight. This new, albeit temporary studio with ample walls, high ceilings, light and open plans would also become a pivot point from which the couple took short trips into European centres for gallery and artists research, and inspiration. Two dedicated trips to Amsterdam in 1990 and 1992 to experience Vincent Van Gogh’s 100-year celebration exhibition and Piet Mondrian’s works close up in Den Haag, especially the Suprematist compositions, as well as days spent in the Stedelijk Museum meant Gordon could quickly return to the Hautvillers studio and work up a dramatic new series, including some of his most famous paintings. The studio’s location in rural France, away from crowds or attention, was another benefit, and Gordon relished the privacy. There were still challenges, however. Being the recipient of the prize meant he had to be ‘on call’ throughout the residency to receive Australian journalists chasing a story, and several scheduled museum trips into Germany, Norway and the Netherlands were cut short because of these ongoing ‘promotional’ visits, which frustrated Gordon. He saw them as interruptions in his research and was never one to chase or embrace publicity.

Over the three decades I knew Gordon, he rarely got excited at the prospect of artworld visitors to his studio space, and actively encouraged ‘work’ meetings off site, usually at his dealers’ galleries or on neutral ground. There were odd, enduring exceptions, with a few close friends invited over, such as theorists Ian McLean and Nicholas Thomas, when they were in Brisbane. The times I saw Gordon really enjoying the company of guests were few, like the day Archie Roach and Ruby Hunter came for an evening barbecue and singalong at the Samford Valley studio during the production of Artists Up Front (1997), a rare exception to his non-participation stance on media projects. Mainly, though, Gordon and Leanne were most relaxed when there was no ‘art agenda’, when Gordon could just be a goofy dad with his daughter Cait and her friends in the pool, or lame dancing in the studio to Eminem, while planning another work. Music in the studio was a frequent accompaniment to making art, and he loved hip-hop and rap, often painting with Ice Cube, Dr Dre, Public Enemy, 50 Cent or NWA in the background, especially in the later years. While he was interested in rhyme patterns, flow and pauses within passages of lyrics, Gordon was more focused on narrative effect, ‘word stacks’ and linkages — interests borne out visually in several of his works.

Another major element of Gordon’s approach to running a studio was the importance of being able to separate ‘art’ from ‘life’, at least in the sense that his working space needed to be separate from his home. During his Macgeorge Fellowship in Melbourne (1993–94), Gordon spent time with artist Lin Onus. Lin operated two properties: one where he lived with his family, and the other, his studio at Upwey in the Dandenong Ranges. As Leanne recounts, it was after talking with Lin and seeing how he worked so productively away from home that Gordon became keen to build a dedicated studio on a vacant block in Samford Valley.1 This would be a way to separate the two sides of his life, and allow him to switch off and spend quality time with family when he returned to Petrie in the evenings.

Simon Wright is Assistant Director, Learning and Public Engagement, QAGOMA. This is an edited excerpt from his essay in the QAGOMA publication Unfinished Business: The Art of Gordon Bennett.

Endnote

1 Leanne Bennett, email to Simon Wright, 10 February 2020.

‘Unfinished Business: The Art of Gordon Bennett’

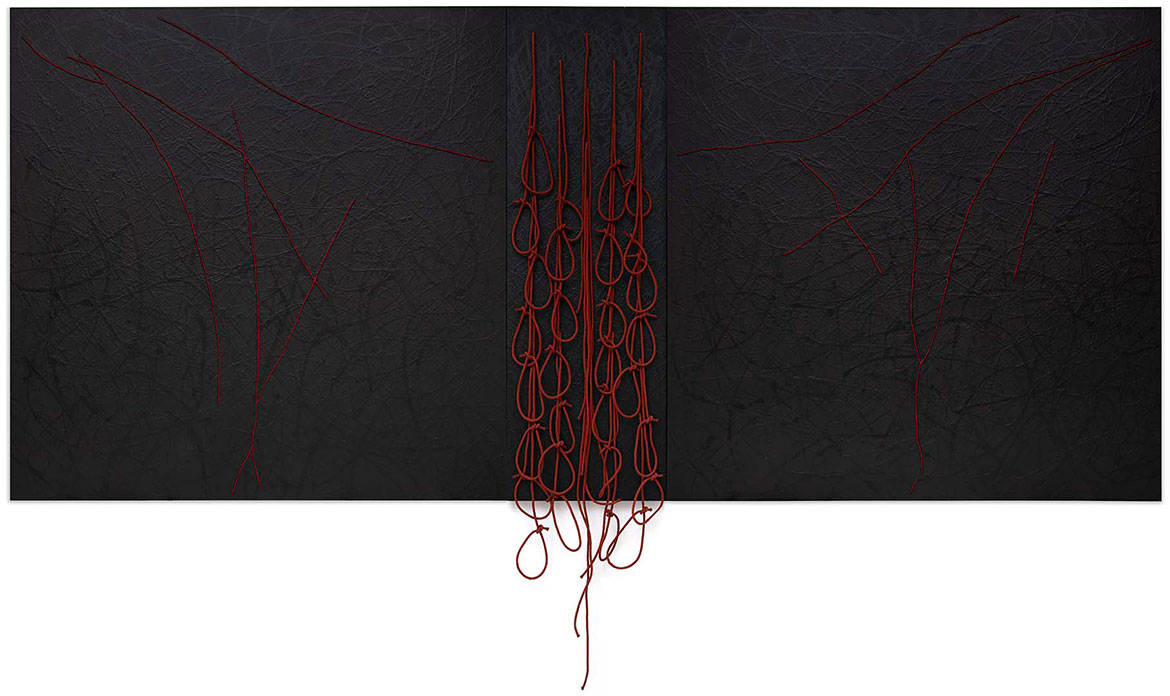

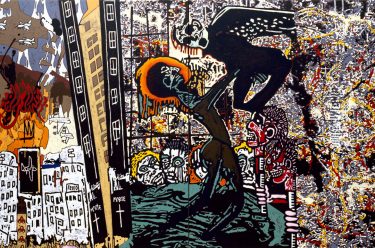

‘Unfinished Business’ is the first large-scale exhibition of Bennett’s work and features 200 artworks ranging from installation and sculptural assemblage to painting, drawing, video and ceramics. In his lifetime, Bennett was widely regarded as one of Queensland’s, and indeed one of Australia’s, most perceptive and inventive contemporary artists. Queensland-born, Bennett (1955–2014) was deeply engaged with questions of identity, perception and the construction of history, and made a profound and ongoing contribution to contemporary art in Australia and internationally.

Bennett voraciously consumed art history, current affairs, rap music and fiction, and processed it all into an unflinching critique of how identities are constituted and how history shapes individual and shared cultural conditions. Working closely with the artist’s estate, the exhibition gives a new sense of Bennett’s aims, ideals and objectives, offering insights through a focus on the serial nature of his practice.

‘Unfinished Business: The Art of Gordon Bennett’ was in the Marica Sourris and James C. Sourris AM Galleries (3.3 and 3.4), Gallery of Modern Art from 7 November 2020 until 21 March 2021.

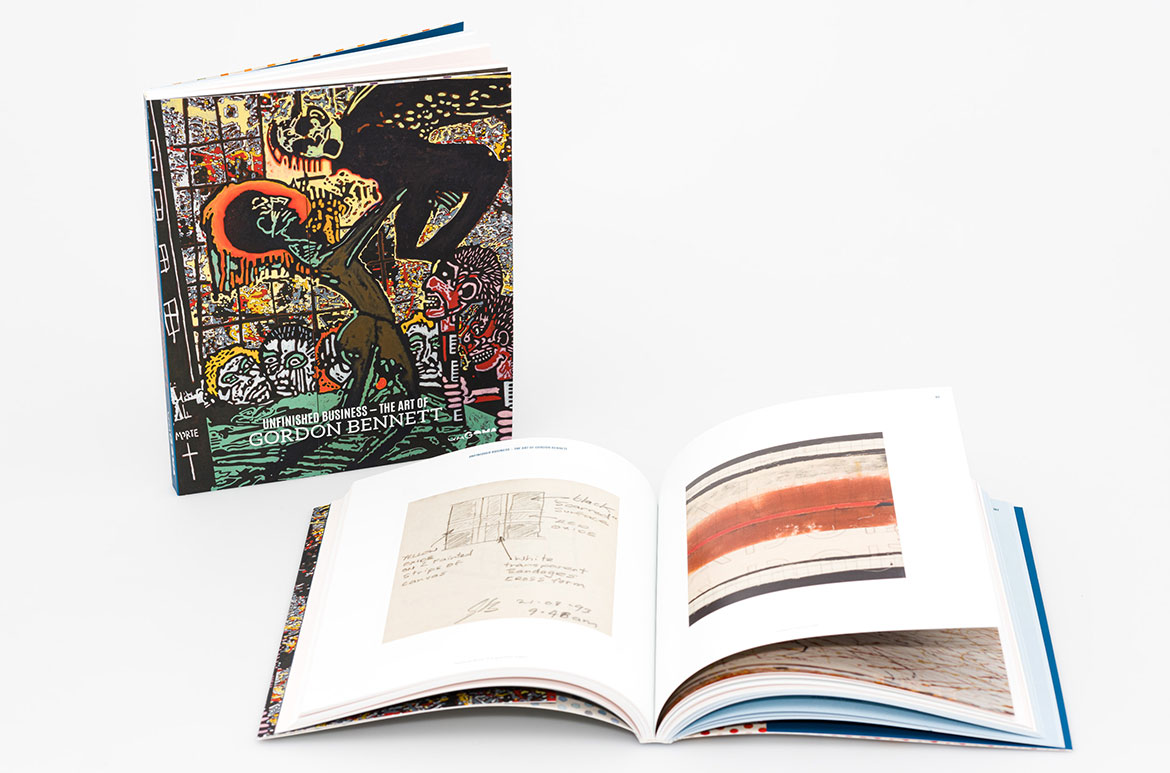

The publication

At 200 pages and with more than 120 colour illustrations, Unfinished Business: The Art of Gordon Bennett includes works created from the 1980s to 2014 sourced from studio, public and private collections, including early installation works; Bennett’s ‘history’ paintings; mirror paintings, De Stijl works; his ‘Home décor’ series; ‘Notes to Basquiat’ works; abstract ‘Stripe’ paintings; and late works showing renewed engagement with political contexts. Pages from the artist’s personal notebooks, as well as archival photographs provided by the Gordon Bennett Estate, provide intimate insight into how the artist worked. The publication has been sponsored by the Gordon Darling Foundation.

Know Brisbane through the Collection / Read more about Australian art / Subscribe to QAGOMA YouTube to go behind-the-scenes

Featured image: Gordon Bennett at the Queensland College of Art, Morningside campus, Brisbane 1987 / Image courtesy: The Estate of Gordon Bennett / Photograph: Leanne Bennett

#GordonBennett #QAGOMA 4-2020

I so enjoyed this exhibition and was fascinated by the language aspect of Bennett’s work. Where may I buy the written material about him? The GOMA shop had sold out.

Hi Mary. ‘Unfinished Business: The Art of Gordon Bennett’ unfortunately has now sold out at the QAGOMA store, it was also distributed through Thames & Hudson Australia but see this is also out of stock. Of interest, there have been recent listings on ebay, more might pop up if you keep an eye out for them. Sorry we can’t be of any more help. Regards QAGOMA