The Australian-exclusive exhibition ‘European Masterpieces from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York’ is the second occasion on which Art Exhibitions Australia (AEA), The Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met), and Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) have come together to present an exhibition, following ‘American Impressionism and Realism’ in 2009. It is QAGOMA’s third collaboration with The Met, which also loaned ‘20th Century Masters from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York’ in 1986.

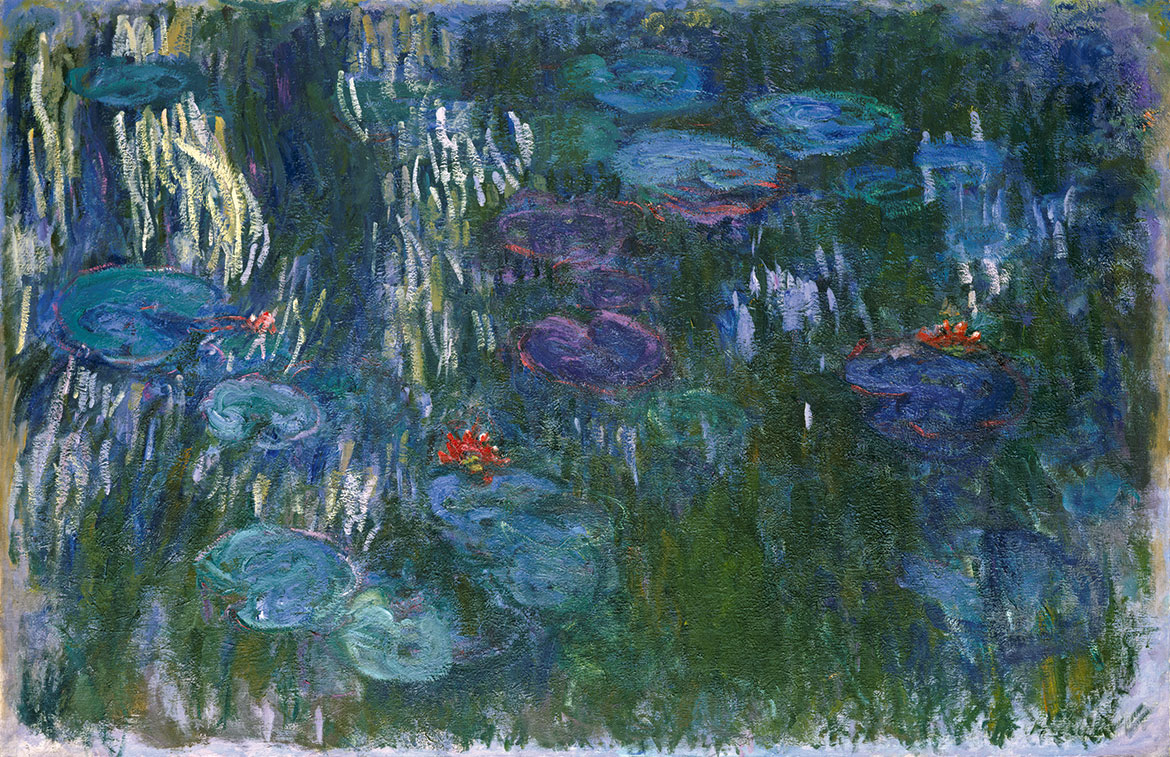

Spanning 500 years, ‘European Masterpieces’ is a breathtaking journey from the emerging Renaissance of the 1420s to the height of early twentieth century Post-Impressionism, including paintings by Fra Angelico, Titian, Raphael, Rembrandt, Turner, van Gogh and Monet. This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to experience works which rarely leave permanent display in New York as part of one of the finest collections of European painting in the world,

With portraiture, still-life, landscape and figure studies, ‘European Masterpieces’ is essential for art-lovers of all ages and anyone with an interest in history, society, beauty, religious iconography, mythology and symbolism.

The following excerpt from the Introduction to the exhibition publication by Katharine Baetjer, Curator Emerita, European Paintings, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, looks at the history of The Met, both as a collecting institution and as a landmark building on New York’s 5th Avenue.

LIST OF WORKS: Discover all the artworks

DELVE DEEPER: More about the artists and exhibition

THE STUDIO: Artworks come to life

WATCH: The Met Curators highlight their favourite works

Beginnings

Americans in Paris on 4 July 1866 celebrated the 90th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence with a reception, speeches and dancing in the Bois de Boulogne. The Union’s victory over the Confederate States in the American Civil War was a recent memory, and in the north-eastern United States, industrialisation and growth were rampant. In a speech to those assembled, New York attorney John Jay noted that it was ‘time for the American people to lay the foundation of a National Institution and Gallery of Art’,1 a suggestion taken up by a committee of the Union League Club of New York. In their October 1869 report, the committee drew attention to the city’s Central Park, which had just opened, and to the new Historical Society and the new Astor Library. Their proposals for an art museum were endorsed at a November meeting by some 300 individuals of standing who were present: all agreed that such a museum should be established and that, in the words of newspaper editor William Cullen Bryant, it should be ‘worthy of this great metropolis and of the wide empire of which New York is the commercial center’.2 On 31 January 1870 the trustees and executive committee were voted into office, with railway man John Taylor Johnston as president, and philanthropist William Tilden Blodgett as second-incommand. The Metropolitan Museum of Art was incorporated on 13 April 1870.

The trustees had neither a collection nor money, which had to be raised. In November 1871, the first object was offered to the Museum and accepted: a Roman sarcophagus presented by Abdo Debbas, American vice-consul at Tarsus. Mr Blodgett had settled in Paris before the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War on 19 July 1870, and in August he bought 57 European old master paintings; in September he acquired a second tranche, of 100 paintings; and in November, a final group of 17 paintings. Each of the first two groups was supposed to represent the holdings of an individual divesting due to financial difficulties arising from the war, and so Blodgett and the trustees believed. In fact, the 174 pictures had been assembled by the dealers at public sales, or from their unsold — because relatively undesirable — stock. Blodgett, who intended the works for the nascent New York museum, offered them at cost in March 1871. Payment was completed in December, funds having by then been raised by public subscription.

The new Metropolitan Museum of Art opened on 22 February 1872 in a townhouse on Fifth Avenue near St Patrick’s Cathedral (which was then under construction). What was there to see? Influenced by the city’s Dutch heritage, the trustees focused on northern European art, with works by Anthony van Dyck (above), David Teniers the Younger and Salomon van Ruysdael. France was represented by Jean-Baptiste Greuze, and Germany by Christian Wilhelm Ernst Dietrich. In the June 1872 Atlantic Monthly, Henry James offered an anonymous assessment. Although there was ‘no first-rate example of a first-rate genius’, he thought that the new collection would be ‘a source of profit to students debarred from European opportunities’.3

In December 1872, Johnston, Blodgett and financier Junius Spencer Morgan authorised the purchase of a huge assemblage of Cypriot antiquities offered by Luigi Palma di Cesnola. This individual had begun life in northern Italy as a military officer, emigrated to the United States and fought for the Union in the Civil War. In 1865, he secured an appointment as American consul in Cyprus. Widescale digging was the order of the day, and Cesnola excavated and exported 5756 pieces before the Ottoman authorities clamped down on his activities. Failing to sell this material to museums in London, Berlin or St Petersburg, Cesnola turned his sights to familiar shores. In 1873, he arrived in the port of New York with hundreds of packing crates. The paintings previously acquired were moved to the Douglas Mansion at 14th Street between Sixth and Seventh avenues, which was large enough to receive the antiquities as well, on a temporary basis. As only the seller knew what the cases contained, Cesnola was hired to unpack, identify and install selected vases, bronzes, terracottas and especially sculptures, including many large limestone pieces from the site of Golgoi.

The first museum building opened without benefit of staff other than security. Trustee and publisher George Putnam then became the volunteer superintendent, with the understanding that a paid clerk would be hired to assist him. The Douglas Mansion was the second temporary home from 1873 until 14 February 1879. When Cesnola returned from a second tour in Cyprus, he was named secretary, and on 15 May 1879 he became the first director, serving until 1904. He and the trustees undertook the move to the new Metropolitan Museum of Art building at Fifth Avenue and 82nd Street. At first, Cesnola was supported by temporary hires. A curator and a librarian were engaged in 1882, and an organisational plan for a managerial staff of 22 was developed for the future. After studying European precedents, another curator was appointed; the first was responsible for paintings (plus works on paper, photographs and textiles), and the second for sculpture (anything that was not flat). Cesnola’s tenure also witnessed the installation of turnstiles, telephones and electric lights in the Museum.

Buildings

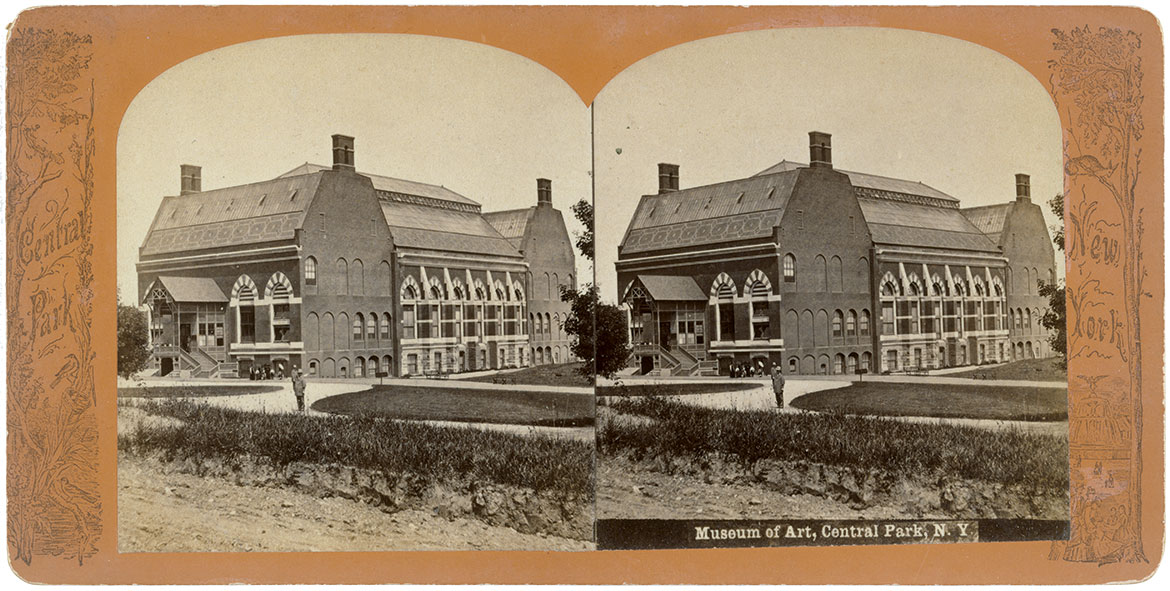

Although park officials had wished to preserve the purity of the laboriously manipulated natural environment of Central Park, architects Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted judged a site at 82nd Street and Fifth Avenue appropriate for a museum or gallery, because the plot, tightly circumscribed, was ‘too small for the formation of spacious pastoral grounds’.4 Its use was designated in 1869, months before The Metropolitan Museum of Art was incorporated. Half a million US dollars was set aside for construction, with the result that both the building and the land upon which it stands belong to the City of New York. Architectural development was haphazard: within 15 years, the original High Victorian Gothic Revival structure (below) had been bracketed by two U-shaped Neoclassical additions of different design to form a square, with crossings and four interior courts. On the main floor were the antiquities, and upstairs the European paintings (the European old masters are still there, under new glass roofs affording controlled natural lighting) (below).

Two major American architects then took charge in succession. Richard Morris Hunt designed the central block on Fifth Avenue, with the Great Hall (below) and a gallery and staircase behind joining it to the original building. These structures were completed in 1902, after his death. The next architect, selected by the third president of the Museum, J Pierpont Morgan, was Charles Follen McKim, principal of the famous New York firm of McKim, Mead and White, who designed the extensions to the north and south in a more restrained classical style. His ambition was to create interiors with light, space, ease of circulation and flexibility, and important parts of these wings (completed in 1922) still serve the Museum’s needs. Hunt and McKim’s 300-metre-long facade is what you see when you approach the building today (below).

Various additional spaces — a library, rooms for European decorative arts, an auditorium and the American Wing — were built contemporaneously and later, with interruptions not only for two World Wars but also periods of economic decline. Thomas Hoving became director in 1966. He and board chairman C Douglas Dillon selected Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo and Associates to implement a master plan, building the various wings outwards in a rectangle, into the park behind the facade (above). Roche flanked the existing structures with glass‑roofed courtyards and glass-curtain walls, designing additions that as much as possible are absorbed into the landscape (opposite). These wings house the Egyptian Temple of Dendur, the collections of donors Nelson Rockefeller and Robert Lehman, and the holdings of modern and contemporary art. The program was completed under Philippe de Montebello in 1990, with money raised by him and his predecessor from private sources. The size of the building doubled to 185 806 square metres to accommodate more than 1.5 million objects. In 2018, The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s three buildings (including The Cloisters in Fort Tryon Park and the Breuer Building on Madison Avenue) received more than 7 million visitors.

Extract from European Masterpieces from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. ‘Introduction’ by Katharine Baetjer, Curator Emerita, European Paintings, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Endnotes

1 John Jay, letter to Museum director Luigi Palma di Cesnola, 30 August 1890, quoted in Winifred E Howe, A History of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1913, p.100.

2 William Cullen Bryant quoted in Howe, p.107.

3 Henry James quoted in Katharine Baetjer, ‘Buying pictures for New York: The founding purchase of 1871’, Metropolitan Museum Journal, vol.39, 2004, p.177.

4 Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, letter to Henry G Stebbins, February 1872, Appendix B, Letter 2: ‘Examination of the design of the Park and of recent changes therein’, Second Annual Report of the Board of Commissioners of the Department of Public Parks for the Year Ending May 1, 1872, William C Bryant and Co., New York, 1872, p.100.

‘European Masterpieces’ publication

The full-colour 240pp hardback publication European Masterpieces from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York was available in two special cover editions — either Caravaggio’s The Musicians 1597 or Marie Denise Villers with Marie Joséphine Charlotte du Val d’Ognes 1801 (illustrated).

This Australian-exclusive exhibition was at the Gallery of Modern Art from 12 June until 17 October 2021 and organised by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in collaboration with the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art and Art Exhibitions Australia.

Featured image: The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 300-metre-long facade from the north-west / © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

#QAGOMA #TheMetGOMA