The Gallery’s major summer exhibition ‘The Motorcycle: Design, Art, Desire’ featured 100 examples of the popular machine spanning more than a century of excellence and eccentricity, with a glimpse into the future with current technological innovations.

An exhibition is most compelling when it provokes greater insight into ourselves, our history and our identity, both individually and collectively. So what has prompted QAGOMA to present an exhibition on the history and future of the motorcycle? Will an audience that finds inspiration in art be equally moved by an exhibition of machinery? Can motorcycles transcend their functional purpose to take us on an emotional or spiritual journey?

‘The Motorcycle’ exhibition was in Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) from 28 November 2020 until 26 April 2021.

RELATED: Suzuki Hayabusa: The world’s fastest production sportbike

The idea has appealed to gallery audiences before: in 1998, the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum in New York presented ‘The Art of the Motorcycle’ to mixed critical response, but, notably, at that time it was also the most popular and well-attended exhibition in the museum’s history, impressing visitors with a form of design that embodies beauty, danger, style, power and freedom. Design-based exhibitions, including those of fashion and architecture, are now part of an accepted ‘blockbuster’ typology, so it’s not a question of ‘why’ so much as ‘why now?’ What new ground will this exhibition claim? The Guggenheim show appeared in the final moments of the twentieth century, neatly and chronologically summarising 100 years of the development of the motorcycle; QAGOMA’s exhibition uses this same history to speak to the future.

DELVE DEEPER: Browse the LIST OF MOTORCYCLES

RELATED: Read more about the bikes in ‘THE MOTORCYCLE’ exhibition

We are 150 years on from the emergence of steam velocipedes — the first experiments in powered, two-wheeled transport. We are also at a pivotal moment of change between the internal combustion engine and an electrically powered future. At such a time, and with access to new and radically different technologies, designers of motorcycles can challenge conventions, discard the baggage associated with outmoded technology and break old rules. The potential of this moment is best understood when the story is told from the beginning.

In the late 1860s, French inventor Louis‑Guillaume Perreaux married a small steam engine to a Michaux bicycle to create the earliest motorised two-wheeled transport. The two-wheeled race to the future had begun, but, for Perreaux, that race was over before he had left the blocks: the principles of the internal combustion engine had already been envisaged with the first working engine firing up in Cologne in 1876. By 1894, Hildebrand & Wolfmüller in Munich began producing petroleum engine-driven motorcycles commercially, with around 2000 manufactured before the end of the century.

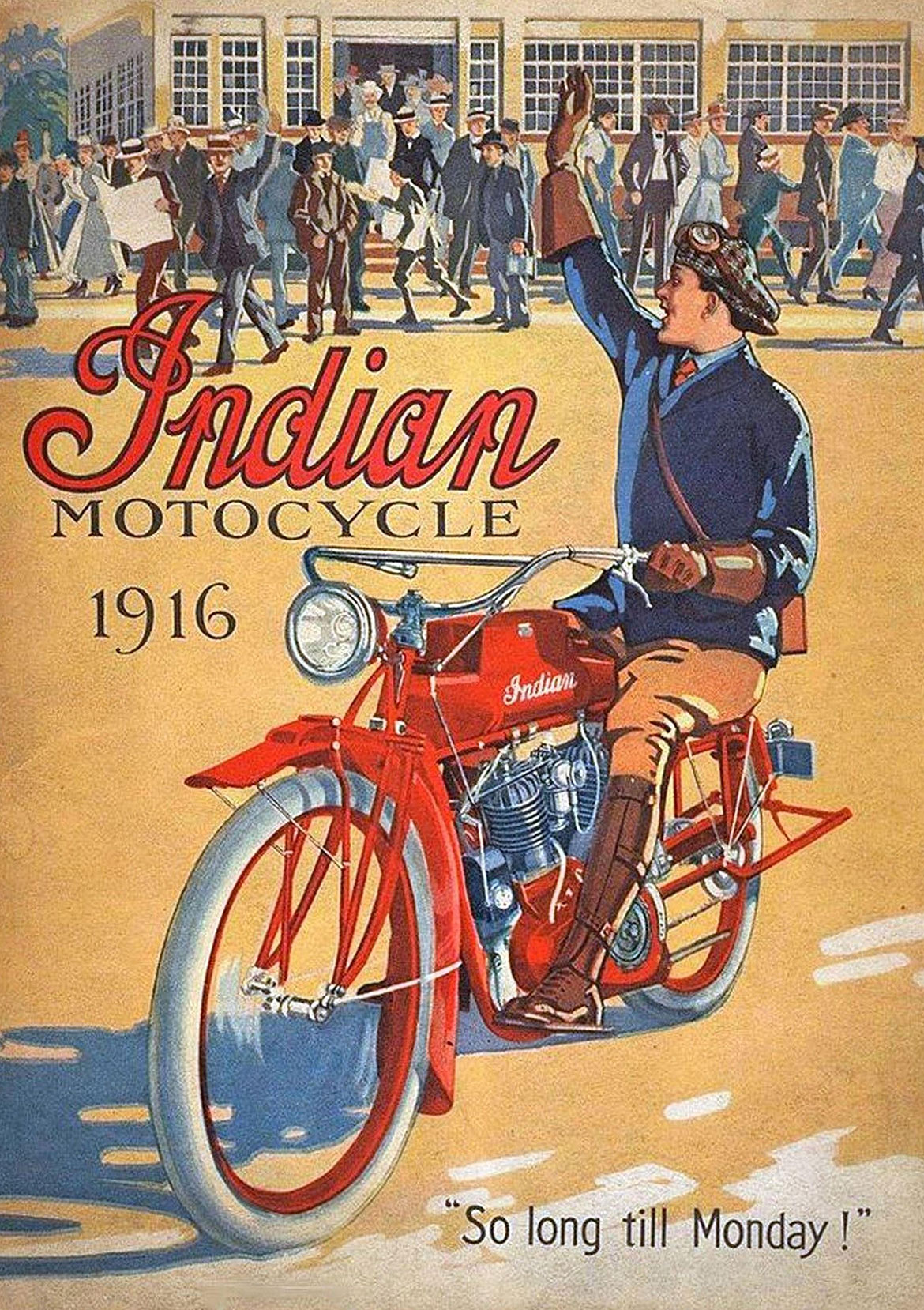

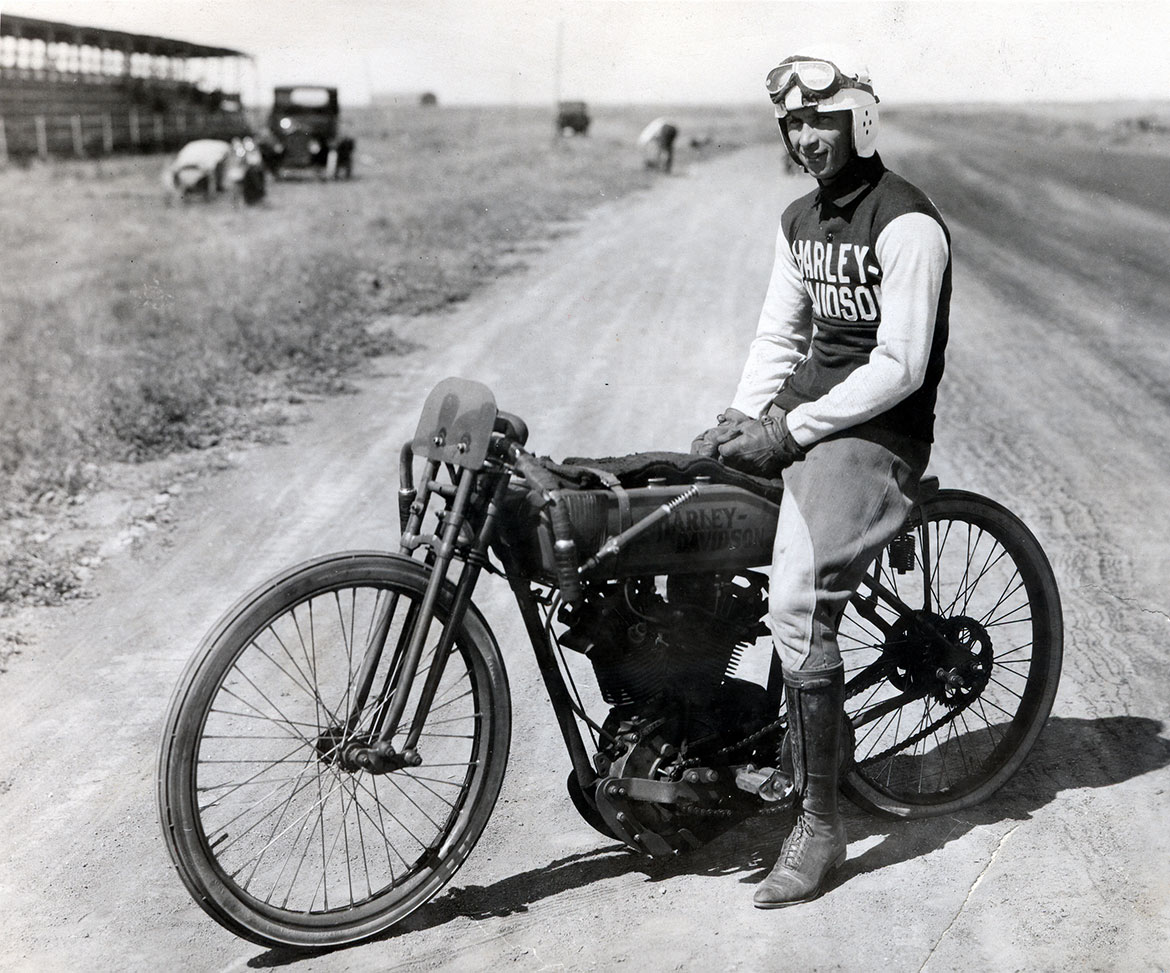

At the turn of the century, motorcycles as we recognise them today began to emerge. These early examples had their own charm and beauty; small internal combustion engines set into ‘safety’ bicycle frames, complete with chain-drive transmissions and pneumatic tyres. The innovations that gave rise to the bicycle boom of the 1890s now made the advancement of the motorcycle possible. Within the space of a few years, there was an explosion of invention, with various forms of internal combustion engine-powered, two‑wheeled transport appearing around the world. In 1902, Triumph launched their first model in the United Kingdom, while Indian did the same in the United States, followed soon after by Harley Davidson in 1905. As we prepared for our exhibition, we discovered possibly the earliest motorcycle designed and fabricated in Australia — the Spencer, created by David Spencer in a shed behind his house in Torwood, Brisbane. ‘Design, Art, Desire’ will include the only known intact Spencer from 1906, number three of ten believed to have been built around this time.

RELATED: Read more about the David Spencer story

As soon as motorcycles were invented, so too were motorsports, with enthusiasts racing each other, and the clock. By 1909, David Spencer was racing his motorcycle competitively where the Gabba cricket ground now stands. Motorcycles quickly evolved in response to the requirements of racing in various conditions. While Spencer’s design was sufficient for powered motion, the introduction of gearing, effective brakes, suspension and increasingly powerful engines soon led motorcycle development in myriad directions. Invention and commercial production were underway from the earliest moments of the twentieth century. The basic design of the motorcycle was established and, for the most part, remained unchanged for the rest of the twentieth century, with very few exceptions.

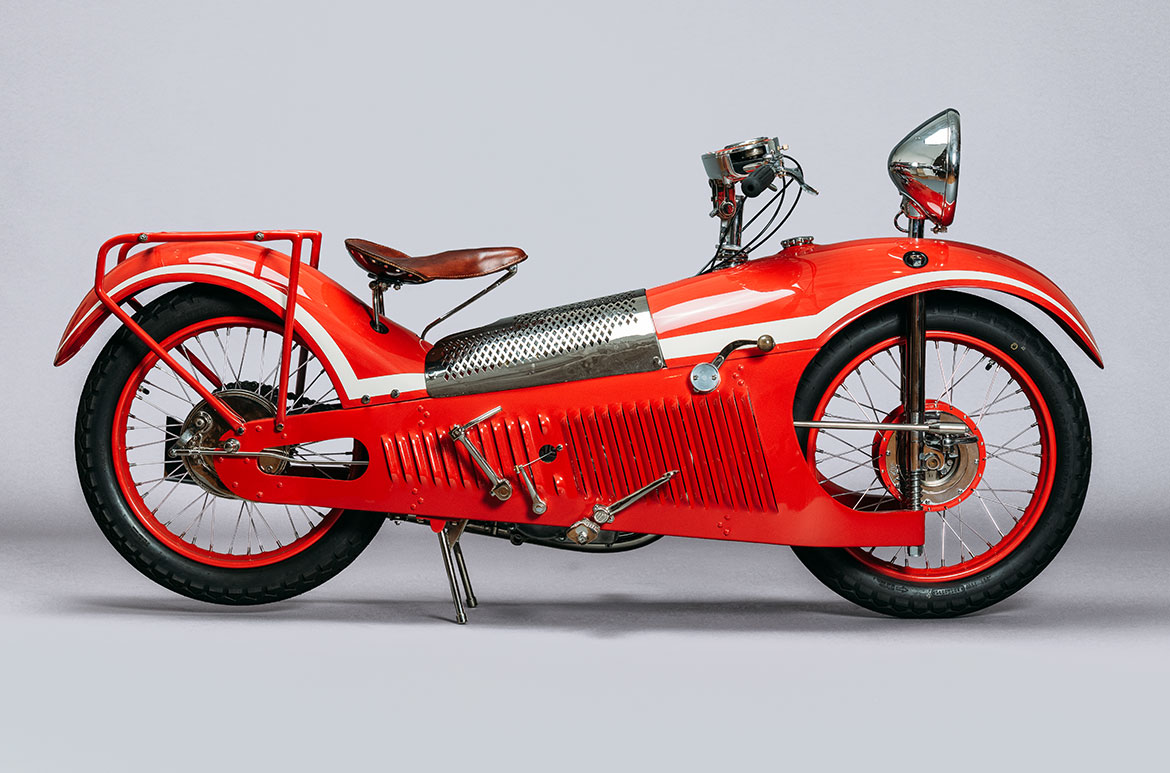

While the emphasis of early motorcycle design was function, within a couple of decades, designs emerged that shifted the focus squarely to form. The design of the Majestic, invented by Frenchman Georges Roy, seemingly drew more inspiration from the Art Deco design movement and stylish European Grand Prix racing cars of the 1920s — like the legendary Bugatti Type 35 — than any motorcycles of the day. With the workings of the machine concealed beneath brightly painted pressed-metal panels, the Majestic was a sculptural object. It was a visionary design for what would ultimately be a commercial failure in the context of the Great Depression, but it established the motorcycle as a truly aesthetic, and highly desirable, work of art.

When Corradino D’Ascanio designed the Vespa for Enrico Piaggio in 1945, he was charged with designing a vehicle that could be ridden by women and men, including priests in their Roman cassocks. D’Ascanio wanted to put Italy on two wheels, but not on motorcycles as Italians knew them. His new vehicle had to be reliable, comfortable, compact, economical, and easy for everyone to ride, no matter the attire. The resulting creation also happened to be elegant, streamlined and iconic. Its pressed-steel monocoque chassis and detachable side panels concealed engine, fuel tank and cables. The step-through frame accommodated all manner of clothing, while leg shields offered protection from road debris and the weather. This beautiful object of design combined commercial and aesthetic agendas so perfectly that it would become one of the most popular and romanticised forms of transport in the twentieth century.

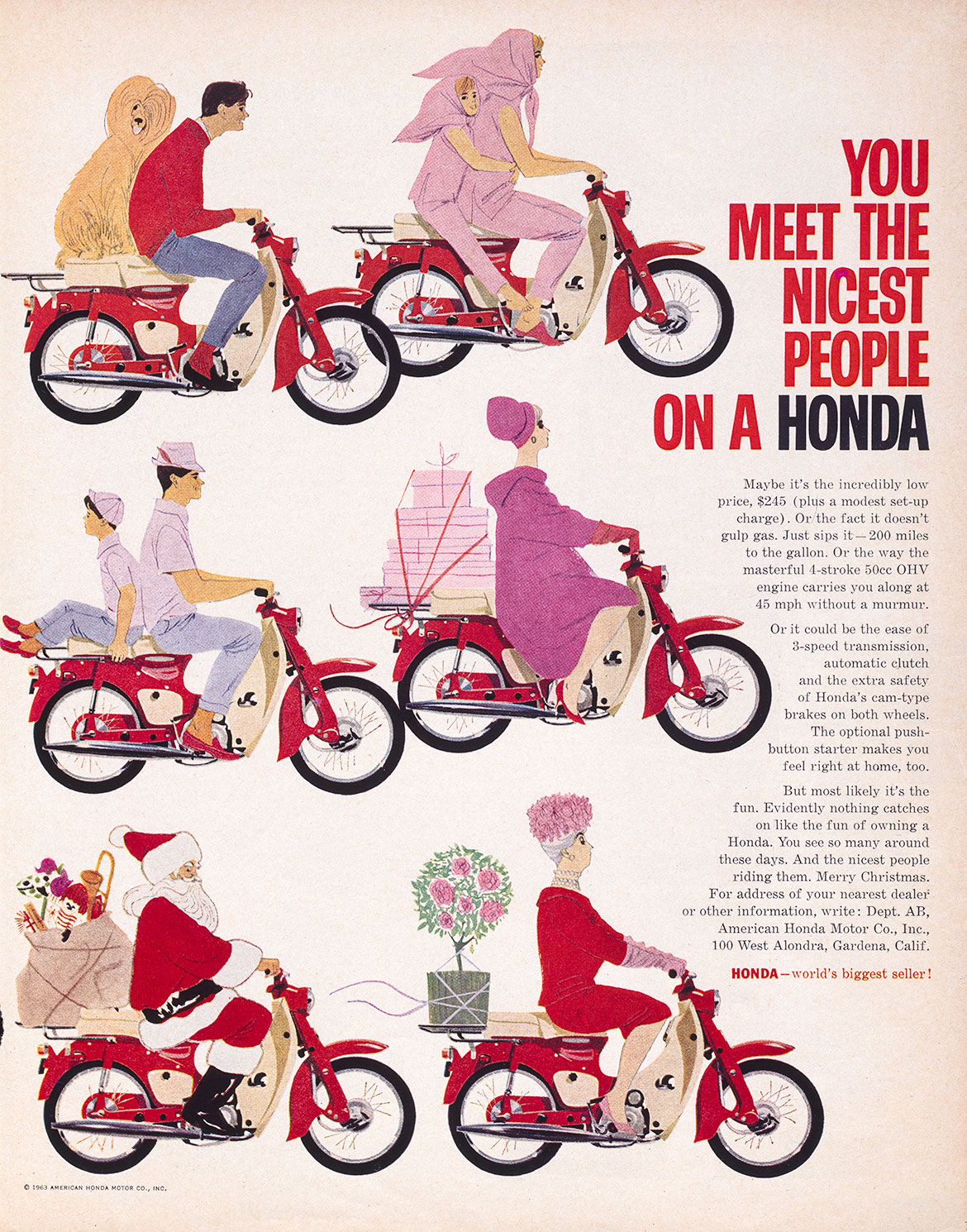

From the post-World War Two boom to the present day, motorcycles have evolved and diversified to address both mass and niche markets. Some makes have become ubiquitous in many parts of the world and have changed very little because they adhere so well to the fundamental rules of motorcycle design and fulfil the demands of the market. Production of the Honda Super Cub, continuously manufactured since 1958, hit 100 million units in recent years, and can rightly take credit for mobilising whole nations in parts of the world. In the Super Cub’s lifetime, thousands of other makes and models have come and gone, but after 60 years, its current iteration still bears a striking resemblance to its first. ‘Design, Art, Desire’ showcases a critical selection of the most important, beautiful and best loved of these machines, and brings them together in one unique story of the motorcycle.

There is a twist at the end of this story: technologies developed over decades are now converging to create something new and radically different. Lithium batteries, LED lights, 3D printing, computer-aided drafting, and the rapid exchange of ideas fostered by the internet are conspiring against the existing rules of motorcycle design and fostering some incredible experiments. Whether it’s the reductive design of the Zooz, which strips away the superfluous elements of old technology; the spectacular Fuller Moto ‘2029’, which reimagines the Majestic as an electric bike from the future; or the completely disruptive Segway Ninebot One S2, which throws out the rule book altogether, one thing is clear: looking forward, the two-wheeled race to the future is promising to be very different to its first 150 years.

Michael O’Sullivan is Design Manager and Coordinating Curator of ‘The Motorcycle: Design, Art, Desire’ at the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) from 28 November 2020 to 26 April 2021.

Read more about Motorcycles / Subscribe to QAGOMA YouTube to go behind-the-scenes

Featured image: Georges Roy’s ‘Majestic’, 1930 / Bobby Haas and Haas Moto Museum / © Haas Moto Galleries LLC / Photograph: Grant Schwingle

Show off your ride with #MotorcycleGOMA #QAGOMA

I am bitterly disappointed with this exhibition which failed miserably to live up to its media hype. The curator of this exhibition has lost a golden opportunity to communicate the skill and value of design both in the past and the present. There are many examples I could make to back up my statement but I shall offer just one; Paul Bigsby was a brilliant designer not just of the Crocker motorcycle but also of the Bigsby guitar which influenced Leo Fender (who he assisted) to create one of the great design icons of the 20C that being the Fender Telecaster guitar. He also designed and manufactured the Bigsby tremolo arm. This is onl one example of the obvious ignorance with which this exhibition was created.

Hi Paul. We appreciate your comments and will pass this on to the curators. Regards QAGOMA

A great show. Thoroughly enjoyed my visit. Yes I looked for some motorcycles that I thought iconic. eg. BMW Rennsport which blew away the opposition prewar. Or the BMW r90s, which transformed BMW’s image from staid reliable transport to reliable sports tourer. But where do you stop and perhaps they are iconic to me and not for everyone.

A great show and thank you to all the museums and families who released their pride and joy for us to see in the flesh and enjoy for a moment.

Regards

John

Hi John, glad to hear you enjoyed the ‘The Motorcycle’ exhibition. Hope to see you back soon. Regards QAGOMA