The story of Judy Watson’s tow row transcends its physical form and speaks of cultural retrieval and community activation. This stunning work, generously funded by the Queensland Government, the Neilson Foundation, Cathryn Mittelheuser AM and others, is a fitting acknowledgment of the ancestor spirit of Kurilpa.

Public art has the power to change the cultural landscape in which it stands. Recently, Judy Watson’s impressive cast bronze sculpture, tow row, was installed in the forecourt of GOMA. Watson’s work was the recipient of the Queensland Indigenous Artist Public Art Commission (QIAPAC), a competitive process that would ultimately see a major work by an established Queensland contemporary artist of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander heritage take pride of place at the entrance to GOMA. The commission is part of a broader project in which the Gallery engages with Indigenous art, culture and community, as highlighted by the recent adoption of its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Engagement Strategy.

Watch | Judy Watson introduces ‘tow row’ 2016

Judy Watson, Waanyi people, Australia b.1959 / Judy Watson with tow row 2016 / Bronze / 193 x 175 x 300cm (approx.) / Commissioned 2016 to mark the tenth anniversary of the opening of the Gallery of Modern Art. This project has been realised with generous support from the Queensland Government, the Neilson Foundation and Cathryn Mittelheuser AM, through the QAGOMA Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art / © Judy Watson

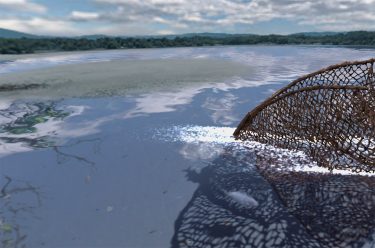

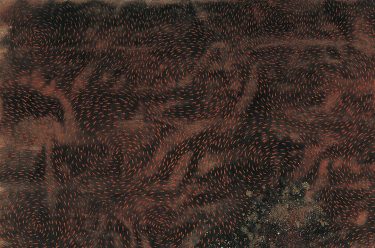

Watson’s sculpture is a reimagination of a traditional fishing net used by Aboriginal people, including on the Brisbane River, barely 100 metres away. The nets, locally known as ‘tow row’, were used to scoop up fish near the banks of the river, or to catch entire schools of fish in smaller creeks, where fishermen would stand midstream during the dropping tide, trapping the fish. Traditionally, this type of fishing was the work of men, and senior fishermen took pride in large bone callouses developed by binding the wooden armature of the nets to their wrists and forearms.1

The importance of the correlation between past, present and future is acknowledged by Watson who, in her initial proposal, noted that:

[The] use of fibre and water as the conduit for catching fish evokes ideas of sustenance, family, culture, survival. The fragility of the object cloaks its hidden strength, a metaphor for the resilience of Aboriginal people who have held onto the importance of land, culture and family through adversity and deprivation. It will be a lasting memory of the indelible Aboriginal presence that is a part of this shared space. Judy Watson

tow row, like so many of Watson’s public works, was the product of a robust, collaborative exchange. No tow row is known to have been made in the last half century, so Watson engaged local Quandamooka weaver Leecee Carmichael and together they examined the weaving techniques of local nets in the Queensland Museum. Carmichael recreated the knotting techniques to make an enormous net with the help of numerous members of local Indigenous and non- Indigenous communities, which was then cast in bronze by UAP (Urban Art Projects), an internationally recognised local foundry with whom Watson has worked for over 20 years.

Mogwaidja is the local language term for the story/place of the spirits of ancestors, equivalent to the dreaming. It explains that the Mogwai (ancestor) whose spirit imbues this area is Kuril, a young female weaver. And so this sculpture of a woven object, and its permanent home at the entrance of one of Kurilpa’s most significant institutions, seems a fitting acknowledgment to the story of this place.

The story of Watson’s work is one that transcends its physical form and speaks of cultural retrieval and community activation. By creating this contemporary public sculpture, Watson enables us to glance at the history of the site. She has also encouraged the renewal of a weaving and netting tradition dormant for decades, and allows us to see a present where local Indigenous art, culture and traditions can stand strong and proud alongside — and in front of — some of the world’s greatest contemporary art at GOMA.

Bruce McLean is former Curator, Indigenous Australian Art, QAGOMA

Endnote

1 Constance Campbell Petrie, Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences of Early Brisbane, University of Queensland Press, Brisbane, 1992 (first published 1904), p.73.

QAGOMA is appreciative of funding from the Queensland Government and generous philanthropic support from the Neilson Foundation, Cathryn Mittelheuser AM, Gina Fairfax, and Professor Susan Street AO, who have made this Commission possible.

Acknowledgment of Country

The Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the land on which the Gallery stands in Brisbane. We pay respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders past and present and, in the spirit of reconciliation, acknowledge the immense creative contribution First Australians make to the art and culture of this country. It is customary in many Indigenous communities not to mention the name or reproduce photographs of the deceased. All such mentions and photographs are with permission, however, care and discretion should be exercised.

#QAGOMA