From its enduring classics to its modern-day interpretations, the continuing social relevance and popularity of the Western film genre is evident, writes Jason Jacob. The Australian Cinématheque presents ‘The Western’ screening until November, a curated program of selected works by filmmakers such as John Ford, Sergio Leone, Clint Eastwood, Takashi Miike, Quentin Tarantino and more.

The vitality and endurance of the Western is a product of that genre’s continuing engagement with something of central importance to the human race: the nature and meaning of settlement under the condition, or shadow, of modernity. In every great Western, such matters are either central to the narrative or infectiously ambient across character and setting, viz., What does it mean to civilise a frontier? Is violence a necessary component of building a safe, productive society? Is the history of settlement, particularly that in the western frontier of the United States in the nineteenth century, one of courageous grasping at Manifest Destiny, or genocidal destruction? What response is available to fight against the emerging impersonal dynamism of large scale capitalist expansion by the fragile frontier communities? Are women civilising forces or an enfeebling restraint on What A Man’s Gotta Do? Once we have safe, secure, domesticated societies, why do we continue to thirst for the heroic individual, the spectacle of violence, the energising clash of principles? Westerns stage the emergent realisation that our morality is intimately tied to our capacity to decide our political and social and communal future: they present the existential question (listen for it in the dialogue), what ought we to do to? Such questions continue to find resonance long after the real historical events of the westering of the US because they are our questions today, too. As world events indicate, we have still not found secure and shared answers.

Often people assume they know what a Western is and what it does, but it can be limiting to think of a genre as merely the sum of variations across a fixed group of elements: black-and-white, cowboy hats, the homestead, saloon, gunfighter, rancher, whore with a heart or Noble Savage on a painted horse. Rather, as philosopher Stanley Cavell argues, a genre is a medium, ‘something through which or by means of which something specific gets done or said in particular ways’1: the Western is a medium that thinks through the questions in the paragraph above in particular narrative and aesthetic ways. Although the genre crosses a wide range of popular and fine art forms (comics, novels, radio serials, painting, photography), its central artistic contribution is instanced in the great Hollywood movies of the twentieth century.

‘Westerns’ were not referred to as such during the early period of cinema: ‘frontier picture’, ‘historical film’ and ‘topical crime picture’ were among the labels given to the short films that were shot on location in outdoor settings, often in combination with some thrilling action moments. The Great Train Robbery 1903, conventionally understood as the first Western, still exhibits some of these elements (although it was shot in New Jersey), but it also reminds us that at that time, the frontier had already become history and therefore a rich source of fiction, as mass urbanisation generated an appetite for mythic foundational stories. Many films of this early period and into the 1920s continued to develop and enrich the emerging genre, but it was not until John Ford’s Stagecoach 1939 that we can genuinely see the genre’s full artistic potential. An apparently simple narrative of seven strangers sharing a dangerous journey across Indian territory is in fact a critical questioning of whether these archetypal figures — all strangers, with no common history or tradition — can find the moral and social resources to survive, live and work together on that journey, and in a new town, a new world. It is the story of the United States and, as such, the journey of the stagecoach driving across the planet is also an emblem of the question of whether a unified nationhood is possible. As Robert Pippin puts it, ‘This turns out to be a question not just about social cooperation but about a higher and more complicated unity — something like a political unity’.2 Ford’s Westerns dominate any account of the genre because of the depth to which they investigate and raise troubling questions about the possibility of such unity: The Searchers 1956, a long and difficult film, is unmatched in the extent of its confrontation with the unsettling fact that, to quote Pippin once again:

. . . the origin of the territorial United States rest on a virulent racism and genocidal war against aboriginal peoples, a war that would not have been possible and perhaps could not have been won without the racist hatred of characters like the John Wayne character.3

What is most troubling about the film is its insistence that our regret and apologies in the here and now for such events may not help us transcend that past. Equally troubling, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance 1962 raises the difficult matter of whether a society that needs to tell itself lies about the past in order to function politically is one worth living in at all.

Along with Ford, the Westerns of Anthony Mann, Howard Hawks and Budd Boetticher (to name some favourites) are fascinating in their patterning of deep moral and political matters that often get perfunctory attention as merely elements in a genre. Nicholas Ray’s outstanding Johnny Guitar 1954 pivots around similar questions of the courage and capacity for violence needed by an individual to defend a settlement against evil; in this case, it is an entrepreneurial saloon-keeper, Vienna (Joan Crawford), fighting for her life against malevolent community leader Emma (Mercedes McCambridge in her best performance). Ray’s film reminds us of the centrality and complexity of the Western’s handling of the feminine: sometimes as a domesticating force that is seen as a limitation, or an ideal; or as a moral and generative figure variously idealised or punished.

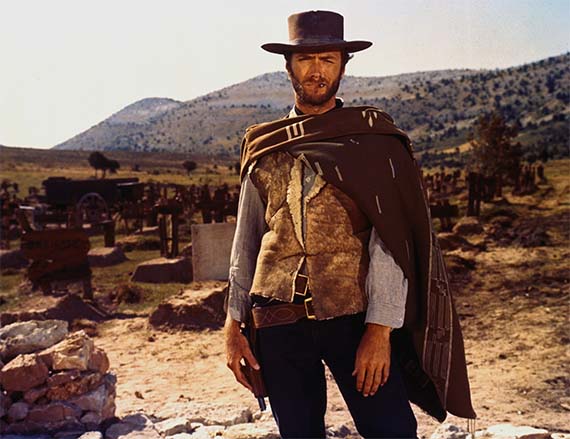

Over the past four decades, Westerns have tended to answer the question of whether civilised settlement is possible or, indeed, desirable, far more pessimistically. Sam Peckinpah’s Westerns already yearned for a world where a homosocial community forged in the common pursuit of order and justice was not corrupted by the temptations of modernity; while Clint Eastwood’s, in a related manner to Sergio Leone’s output, see a world in which individuals with the skilled capacity for violence are incompatible with the rest of society but will not disappear from it. Modern films in the genre, such as No Country for Old Men 2007, depict societies where the figures of law are ‘overmatched’ by both corporate and individual evils.

But there are grounds to be optimistic, and some recent instances of the genre can help us navigate that. Nicolas Ray’s The Lusty Men 1952, set in the world of rodeo stars, suggests that yearning for a safe domestic life is not some conformist submission to a suburban dream: it has substance, and allows the generative pressure of companionship and family to flourish. Deadwood (2003–06), the HBO television Western, stages a primordial world of mud and violence in a gold-mining town in the 1870s, pulling together the threads of damaged, violent and criminal individuals who, despite themselves, build a community (almost) sufficient to defeat the malign forces of capitalism. Finally, Nic Pizzolatto’s True Detective (2014–15) combines noir atmospherics with the moral search for meaning characteristic of the Western medium, depicting a world where civilisation or settlement is vanishing, leaving behind the moral and industrial wastelands of Louisiana and Los Angeles. In those worlds, as in Stagecoach, characters who share no history have to muster the resources of hard work, wholeheartedness and companionship in order to imagine that a better world is possible.

Jason Jacobs is Professor of Screen Aesthetics and Head of the School of Communication and Arts at the University of Queensland. He is author of Deadwood (BFI TV Classics, British Film Institute, 2012) and co-editor of Television: Aesthetics and Style (Bloomsbury Academic, 2013).

Endnotes

1 Stanley Cavell, The World Viewed: Reflections on the Ontology of Film, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Harvard University Press, London, 1979, p.32.

2 Robert B Pippin, Hollywood Westerns and American Myth: The Importance of Howard Hawks and John Ford for Political Philosophy (The Castle Lectures in Ethics, Politics, and Economics), Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2011.

3 Pippin.