Changes in our media technology and consumption, along with changes in the concept of the art museum itself, have sparked a renewed interest in performance art. Bree Richards explores the issues behind the medium as well as what to make of what remains once the ‘show is over’. Opening tomorrow at the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA), ‘Trace: Performance and its Documents‘ brings together new commissions with historical and contemporary works from across the Gallery’s Collection.

Performance art has undergone a resurgence in recent years, moving from the margins to the centre of contemporary art discourse. Several key museums have established departments, appointed curators, built spaces for presentation, and are now raising questions about how to collect and preserve performance.1 Alongside this marked increase in the number of works and venues, the medium has been embraced by new audiences around the world in ways that would have been unimaginable to artists working in the 1970s. Think of the effect that Marina Abramović’s endurance work The Artist is Present 2010, at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, had on the people who waited for many hours in long lines to sit across a table from her. Captured in a documentary seen by many more people around the world than saw the work at MoMA, the camera recorded the artist as she endured thirst, hunger and physical pain, as well as the responses of visitors confronted by her placid gaze — some wept,2 while others variously vomited, took their clothes off or proposed marriage. Just this year, music mogul Jay-Z presented his own take on Abramović’s work, as the basis for a video for his song about collecting art (‘Picasso Baby’), by rapping for six hours in front of art-world VIPs, including Abramović herself. The viewers’ response, however, was primarily to get up and dance.3

This renewal of interest in performative forms of art is being driven by a number of overarching factors: the abundance of new technologies has had a huge impact on the reception of performance, as it is now easier than ever to document and distribute; a growing trend towards self-surveillance and public sharing via online platforms and social networking; and the rise of mass media and a celebrity-obsessed culture. We live in a time that is essentially awash with ‘performance’, and the massive shifts occurring today are similar in scale to those that took place at the beginning of the twentieth century. For the Italian Futurists in 1909, the train, car and plane were the basis for an evolving aesthetic. They were responding to the speed and thrill of these high-powered machines, transporting information and people around the world at unprecedented speeds. Today’s equivalent is the computer, and specifically, the internet, alongside a raft of ever more advanced technologies spinning us ever faster into the future.4

Art museums have also changed dramatically. From places of quiet contemplation, where visitors spoke in whispers in the hallowed halls of art history, they have been recast as active, communal spaces, where large audiences can congregate and, with increasing frequency, encounter art as a physical experience.5 A number of works in the Gallery’s Collection come to mind, which have variously seen visitors whooshing down a two-storey slide (Carsten Holler’s Left/Right Slide 2010), eating a meal with strangers (Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Untitled (lunch box) 1998) or listening to improvised music created by families of finches flitting between harpsichord strings (Celeste Boursier-Mougenot’s from here to ear (v.13) 2010).

It’s true that, across time, artists have always painted, sculpted and drawn the human form. Yet recent art history has revealed a major shift in the way artists’ perceive the body: as ‘content’ of the work, but also as brush, frame, canvas and platform. Performance has been at the forefront of these developments for more than a century now, during the 1960s and 70s physical bodies were increasingly used to challenge the pretence of traditional artistic representation, and subsequent works were associated with an escape from the conventional museum with its wall- and plinth-based art.6 The fact that this era — which today is considered the ‘golden age’ of performance and conceptual art — is now history, also means the stories surrounding these works are now increasingly being told in contemporary art museums.

Mention of these ‘stories’ brings us to sticky questions regarding presence and absence — the apparent contradiction that lies at the heart of all performative practice. The upcoming exhibition ‘Trace: Performance and Its Documents’ seeks to explore this conundrum. It might seem obvious when talking about performance that ‘you really have to be there’, in the flesh, to get the story right. Yet if performance is only ever about presence, then what are we to make of the many traces it leaves behind?

While the experience of ‘being there’ certainly adds something particular — a subjective and personal relationship between an audience and an artist or performer — it is still possible to experience the work at a remove, whether via a screen, photographic documentation, or even a third-hand retelling of the action. In fact, geography and a lack of access to a time-travelling device mean the material produced for, about or during performance is the only way most of us can ever encounter these works. Historically, live work has become synonymous with its documentation, and in fact this is now a strength of art museum collections.

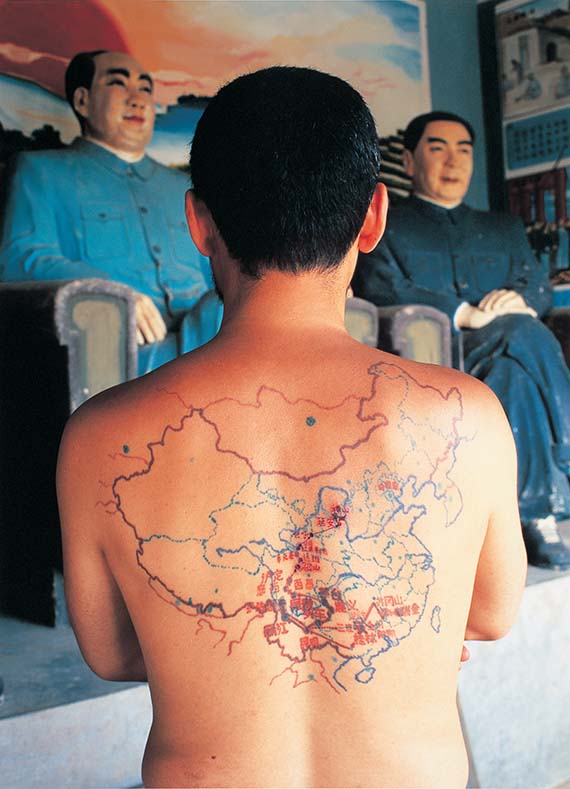

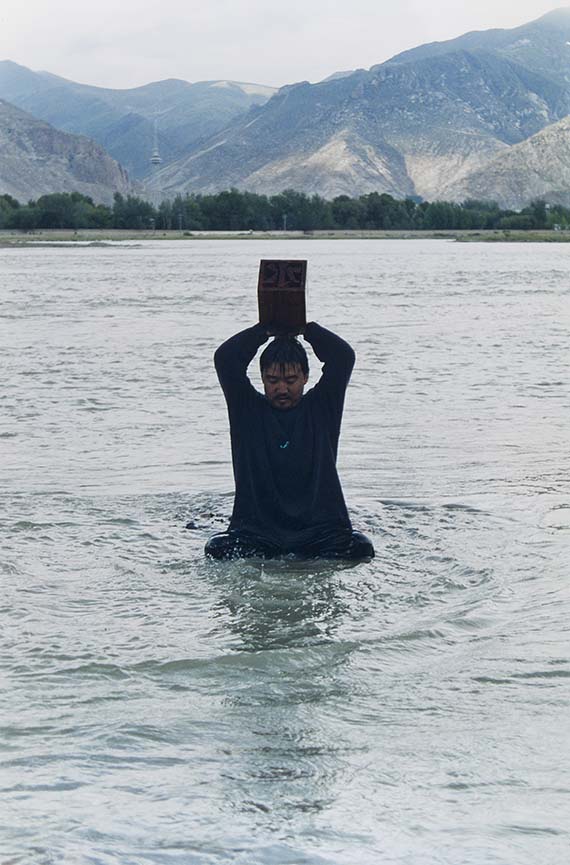

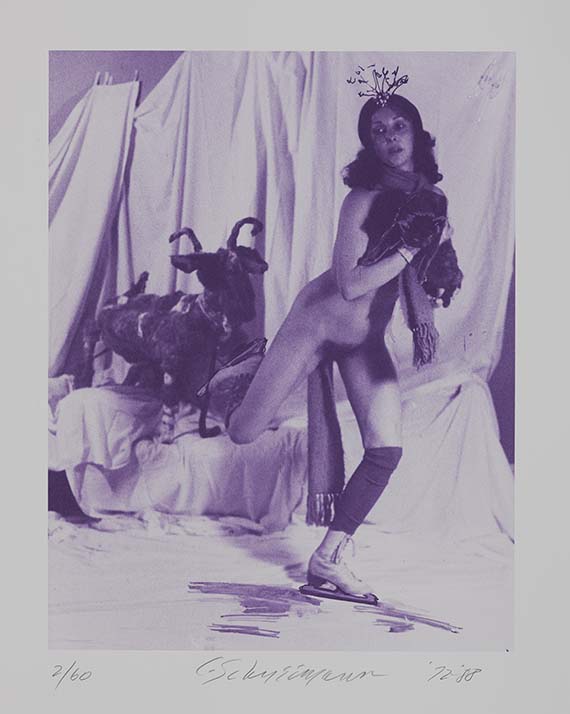

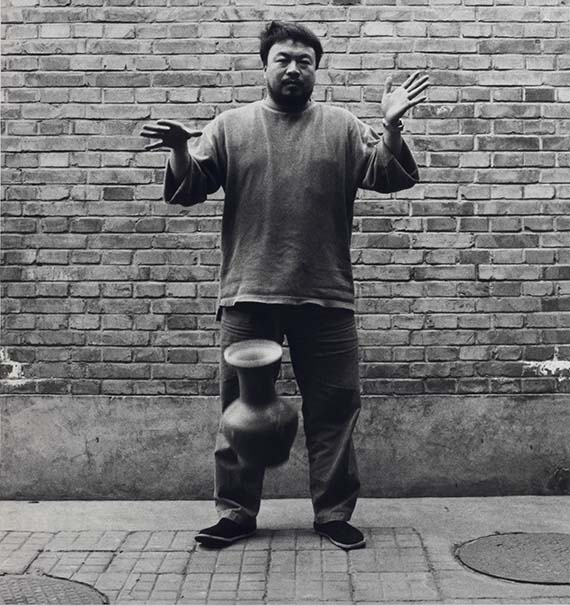

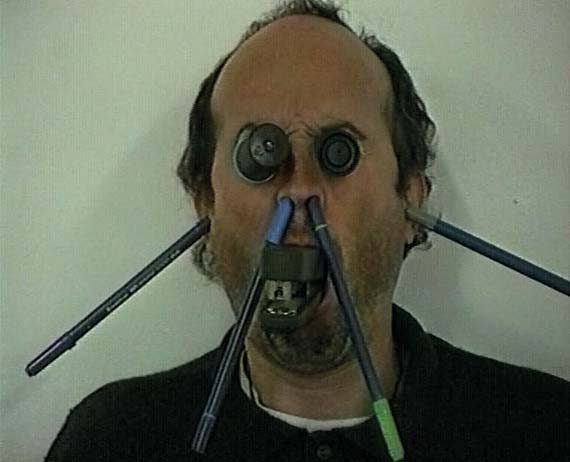

‘Trace’ draws out the relationship between temporal and embodied practice and its documents, bringing together new commissions with historical and contemporary works from across the Gallery’s Collection. The exhibition includes works by artists such as John Baldessari, Rebecca Horn, Bruce Nauman, Mike Parr, Campbell Patterson, Qin Ga, Carolee Schneemann, Sriwhana Spong, Song Dong, Stelarc, Ai Weiwei, Gosia Wlodarczak, Erwin Wurm, Zhang Huan and more. Spanning an array of cultural contexts and varying forms of performativity — feats of endurance, repetitive actions, shamanistic rituals and vaudevillian acts — the works in this exhibition also range wildly in tone: from the sublime to the icky to the out-and-out funny.

Alongside a key interest in questions of presence and absence, and in the body, ‘Trace’ explores several core themes. A number of works are about the gesture: simple bodily acts, behaviours and everyday situations are transformed into art, and the artists’ or others’ bodies are both object and subject. Another group of works deals with ritual and transgression in performance practice, where the body is treated as material with which to challenge social expectations, often in rituals that sought to perform a cathartic function. From here we turn to works that examine body boundaries — between the inside and outside of the body itself, and between the individual and social environment. Elsewhere, artists seek to extend the body through prosthetics, exploring alternative states of consciousness, transforming it into something more than human. Others take performance itself as subject, and so too, performing the subject — to investigate issues of representation and identity. And finally, there are those that deal with the echoes of performance. In these works, the body is often notably absent, yet the works carry a psychological imprint, the suggestion of a physicality after now, and are as much about that which remains as the original act involved in its creation. Whether recorded images, texts, objects or other remains, ‘Trace’ gives presence to the tangible residue of a performance. Alongside the works themselves, these remnants testify to the relevance of ephemeral work in the art museum: it appears, disappears, then reappears in various guises.

Endnotes

1 RoseLee Goldberg, ‘The performance era is now’, Art Newspaper, issue 240, 9 November 2012, <http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/The-performance-era isnow%20/27883>, viewed 8 October 2013.

2 There’s even a dedicated Tumblr: ‘Marina Abramović Made Me Cry’, <http:// marinaabramovicmademecry.tumblr.com/>, viewed 8 October 2013.

3 Emma Allen, ‘The rapper is present’, New Yorker, 11 July 2013, <http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/culture/2013/07/jay-z-marina-abramovic-pace-gallery-picasso-baby.html>, viewed 21 October 2013.

4 RoseLee Goldberg, interview with the author for das Super Paper, no.26, Sydney, March 2013, p.34.

5 Goldberg.

6 Tracey Warr, ‘Preface’, The Artist’s Body, Phaidon, London, 2000, p.11. ‘Trace: Performance and Its Documents’ opens at GOMA on 22 February 2014.