If you ask, nearly everyone seems to have a place to travel to in mind — for a holiday, family reunion, destination for study or work, the site of some natural wonder or another culture of interest. Travel can be an incentive, or a consolation for the present moment. Flights of fantasy are dreamt and booked. We bring objects and insights back with us, and often leave something behind, too.

With an inquisitive mind and open attitude, we become travellers of some sophistication. Of course, most of our day-to-day travels are brief and seem better described as a chore, the protagonist merely a commuter. Repetition primes us to become weary and jaded, yet familiarity can also be comforting, and being alive to the smallest changes in our surrounds, the seasons, a plant in bloom, a startled animal, even a rock out of place, can offer a similar kind of stimulant for the spirit if we let it — as in the work of English ‘walking artist’ Hamish Fulton, or Takahashi Hiroaki of modern Japan’s shin-hanga movement.

Takahashi Hiroaki ‘Figure with snow falling’

Not all passages take place under such tolerable (or should that be tolerant?) conditions, and a traveller from somewhere else might not be seen as a traveller at all. Instead, they are considered an outsider, a stranger, bohemian, drifter, foreigner or alien. More and more, people crossing borders in search of safety are being referred to as illegal, recast as fugitives instead of casualties, and their movement is treated with fear and suspicion.

JMW Turner ‘The Temple of the Sibyl, Tivoli’

Tivoli was a favoured destination for wealthy European ‘grand tourists’, who often spent years, and fortunes, engaging in the latest fashions and culture of Europe for reasons of self-improvement. When JMW Turner visited Tivoli on his first journey to Italy in 1819, he was so struck by the area that he devoted an entire sketchbook and several watercolours to it. An early watercolour by Turner — The Temple of the Sibyl, Tivoli c.1794–97, however, predates his visit, it was most probably copied from another artist’s work as an exercise. Turner’s watercolour is a curious invocation of a place not yet visited, and likely a tribute to its reputation as a worthy destination.

RELATED: The life and art of Jeffrey Smart

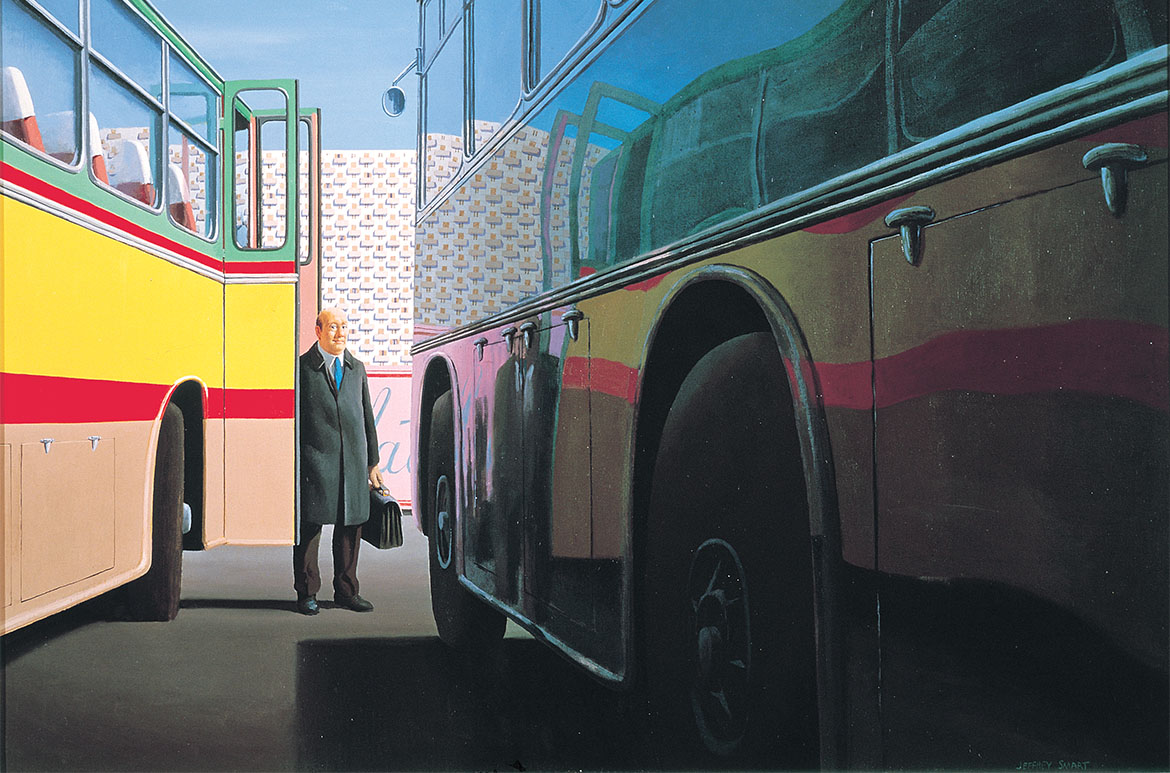

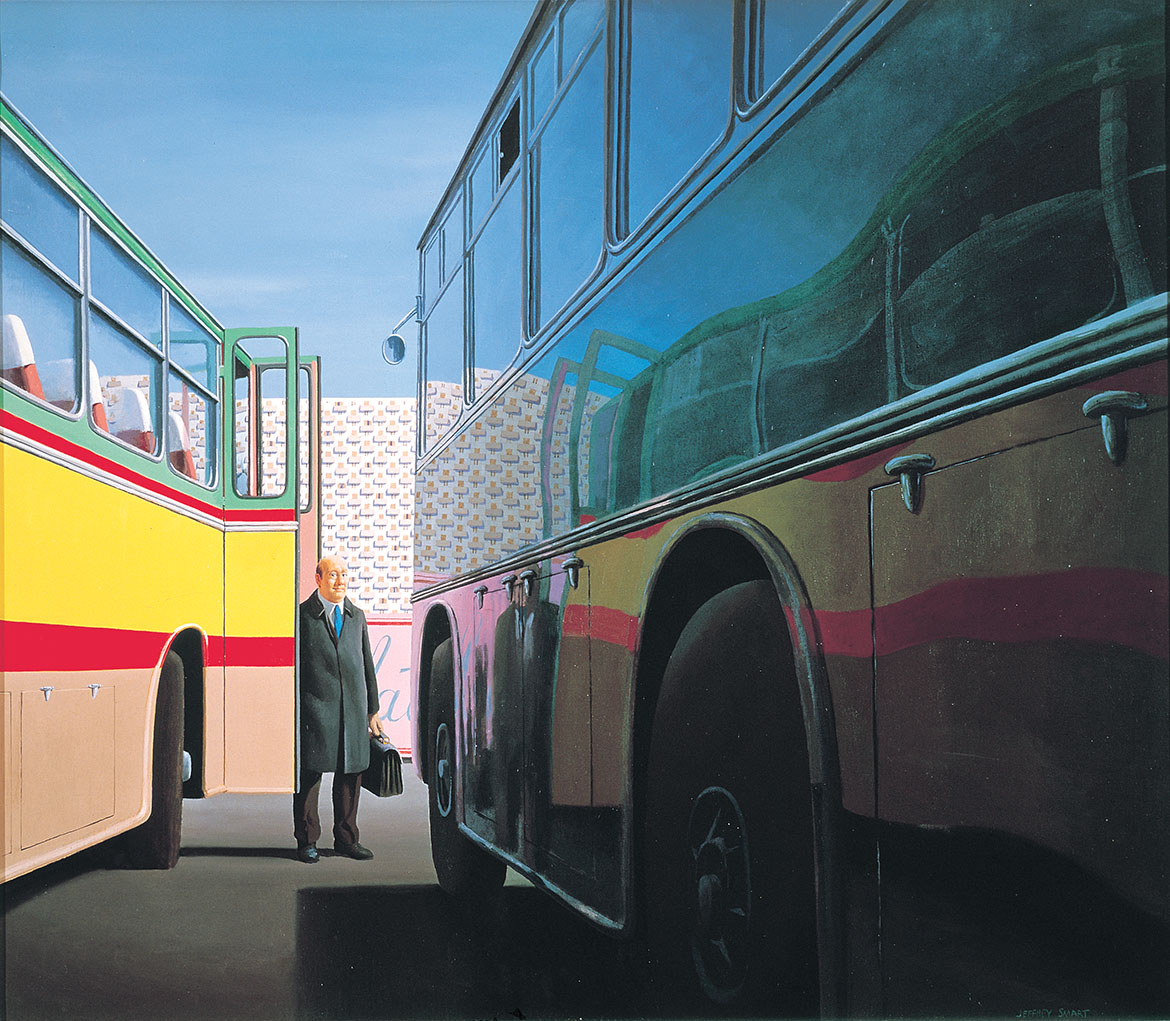

The work is rigid and upright, painted before his swirling storms of colour, and corresponds neatly with Australian painter Jeffrey Smart’s The reservoir, Centennial Park 1988 and The traveller 1973. Known for his meditative arrangements of modern construction, Smart’s vision aligned with the serene order of early Renaissance artist Piero della Francesca, in particular, and in The reservoir, Centennial Park he evokes a similar humanistic appeal. In this painting, however, the ‘tours’ of its figures seem rather less grand, navigating the everyday surrounds of asphalt and concrete with their swift strides and laboured steps.

Jeffrey Smart ‘The reservoir, Centennial Park’

Jeffrey Smart ‘The traveller’

Ancient Chinese water vessels point to the long historical importance of transporting water; what was once an errand is now infrastructure. In the large-scale ‘still life’ Travellers no.3 2001, Australian potter Gwyn Hanssen Pigott also refers to this history, but operates in another symbolic realm. Her ‘families’ of cups, bottles and bowls appear to stand together in groups, while others drift apart — as do people throughout their lives. Here, Hanssen Pigott finely orchestrates a combination of contours and spacing, alluding to the push and pull of human experience.

Gwyn Hanssen Pigott ‘Travellers no. 3’

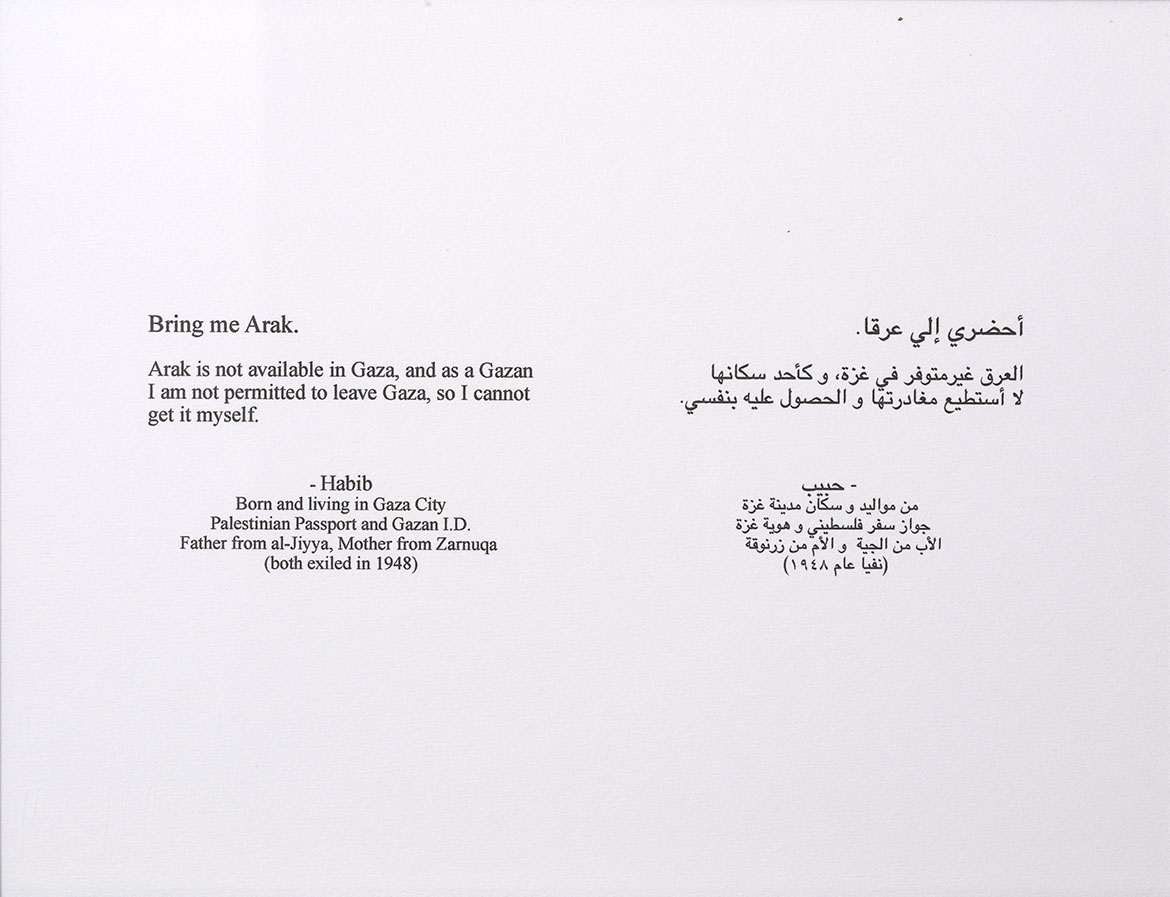

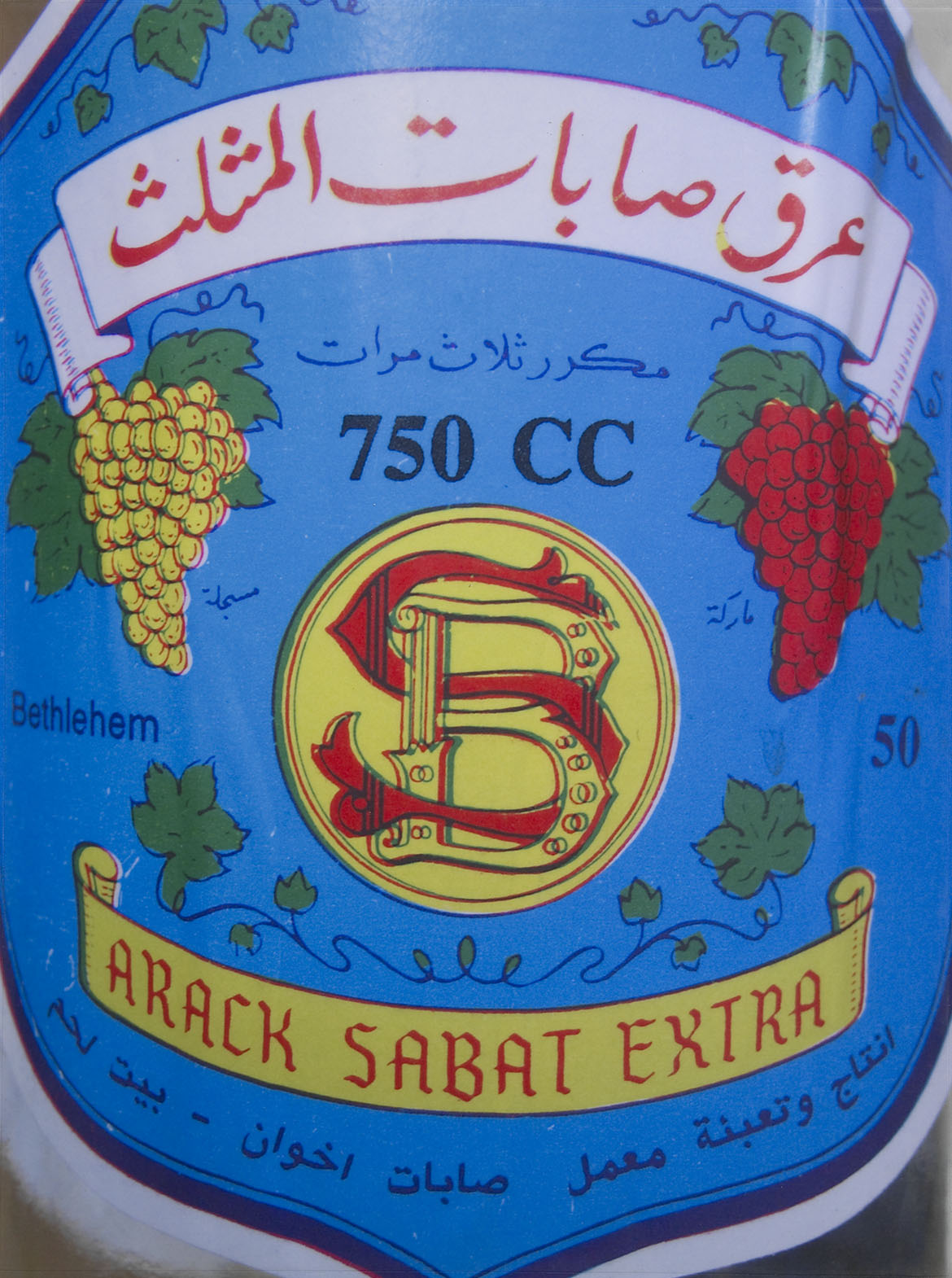

Palestinian artist Emily Jacir uses her freedom to travel to respond to a complex political situation. Much of Jacir’s work is predicated on the relative ease with which she can travel between her studio in New York and her family home in the West Bank city of Ramallah — a region the United Nations describes as an Israeli-occupied territory — owing to her United States citizenship. For the series ‘Where we come from’ 2001–03, Jacir asked Palestinians living in exile: ‘If I could do anything for you, anywhere in Palestine, what would it be?’ Documentation of the artist’s attempts reveals something of the poignant ways in which such restrictions have influenced individual lives. President Trump’s recent travel bans and the ‘extreme vetting’ being implemented in the US might soon generate alternative readings of this series.

Emily Jacir ‘Where we come from (Habib)’

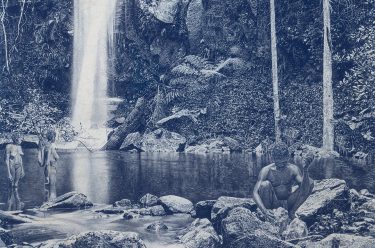

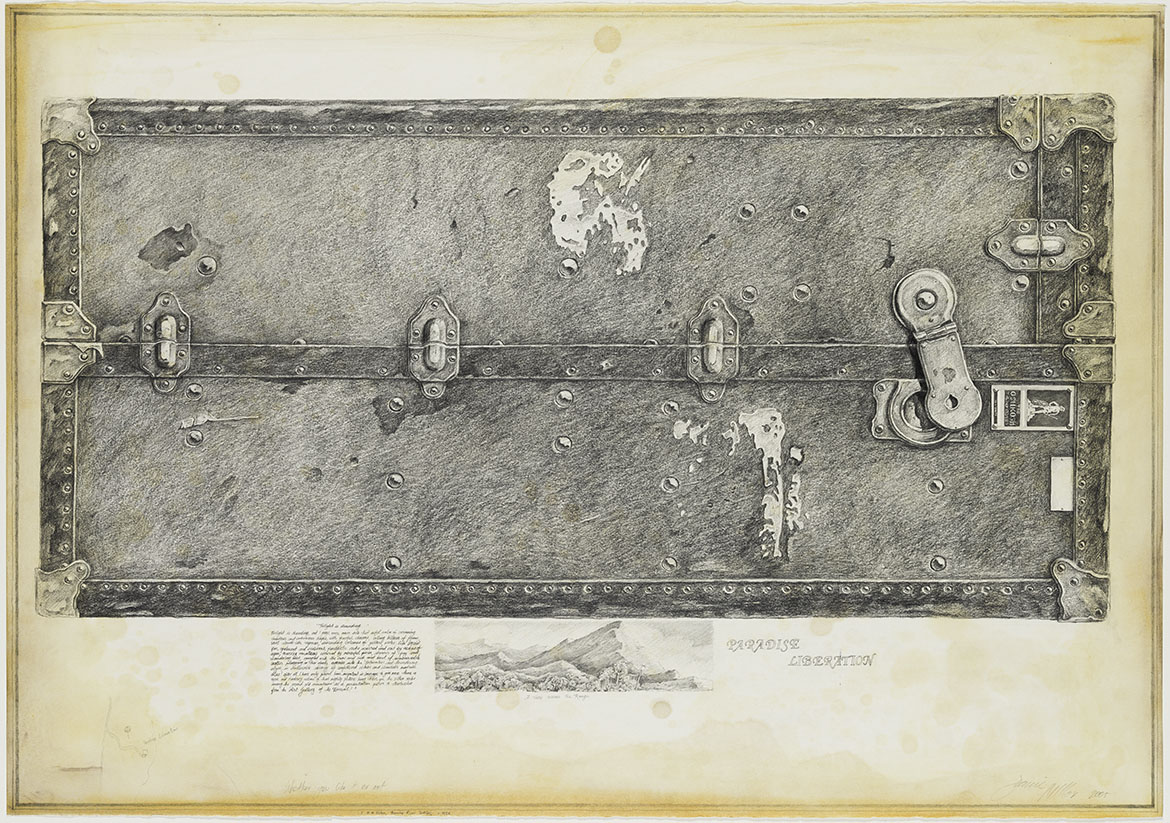

Aboriginal artist Danie Mellor echoes Jacir in the drawing Whether you like it or not 2005. The image of an antique travelling trunk signifies an Aboriginal diaspora and the involuntary circumstances under which they were made to travel. Under the trunk, a sketch of a mountain range shows Mellor’s traditional lands around the Atherton Tableland. Next to this, the words ‘paradise’ and ‘liberation’ appear multiple times. These are, in fact, the names of deluxe models of campervan — from a latenight television advertisement that resonated with Mellor — being promoted to consumers for the purpose of unhindered travel; contrasting with the movements of the country’s original inhabitants, who were forced from their country onto reserves and settlements.

RELATED: Danie Mellor

Danie Mellor ‘Whether you like it or not’

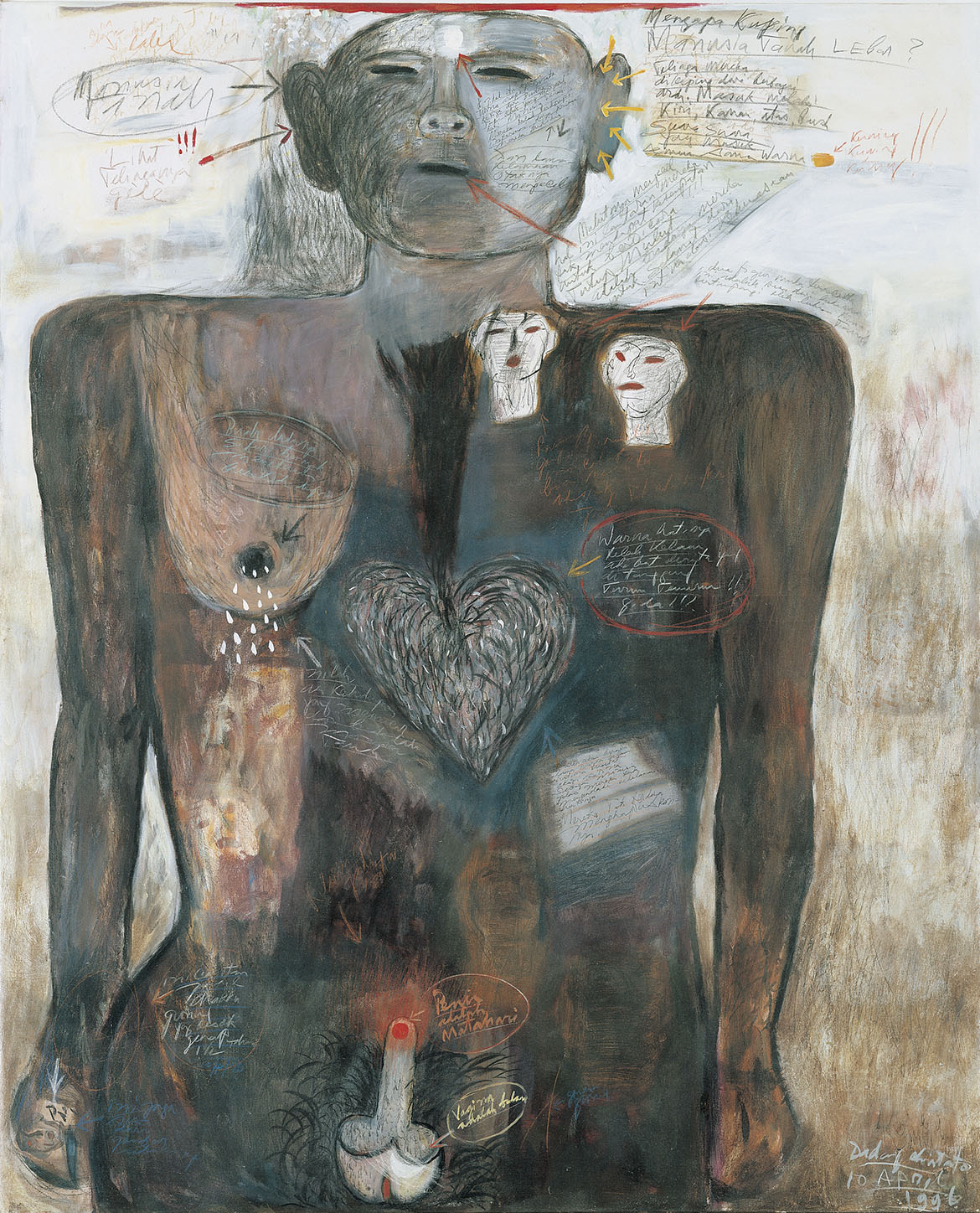

Taking a wider lens still, Dadang Christanto draws on his Indonesian heritage, specifically the rich coexistence of Hindu and Muslim religious cultures. His Manusia tanah (The earth human) 1996 makes reference to the half-female, half-male Hindu deity Ardhanarishvara — the composite form of the Hindu god Shiva and his consort, Parvarti — traditionally depicted as a positive balance of feminine and masculine forms and energies.

Dadang Christanto ‘Manusia tanah (The earth human)’

In Christanto’s version, however, the heart is swollen and dulled by suffering, the diminished skull suggests an incapacity for critical thought, and a red arrow points to the empty space on the figure’s forehead where an urna (the symbol of the third eye, signalling divinity) would normally appear. In taking a mortal body, the deity now lacks adequate insight and travels through life in a form that harbours a predilection for violence. These misfortunes are tempered by symbols of procreation and the milk of life, signalling continuity and prosperity. Christanto’s Ardhanarishvara captures the imperfection of our life journey, from birth to death through fear, love and decay.

Peter McKay is Curator, Contemporary Australian Art, QAGOMA

#QAGOMA